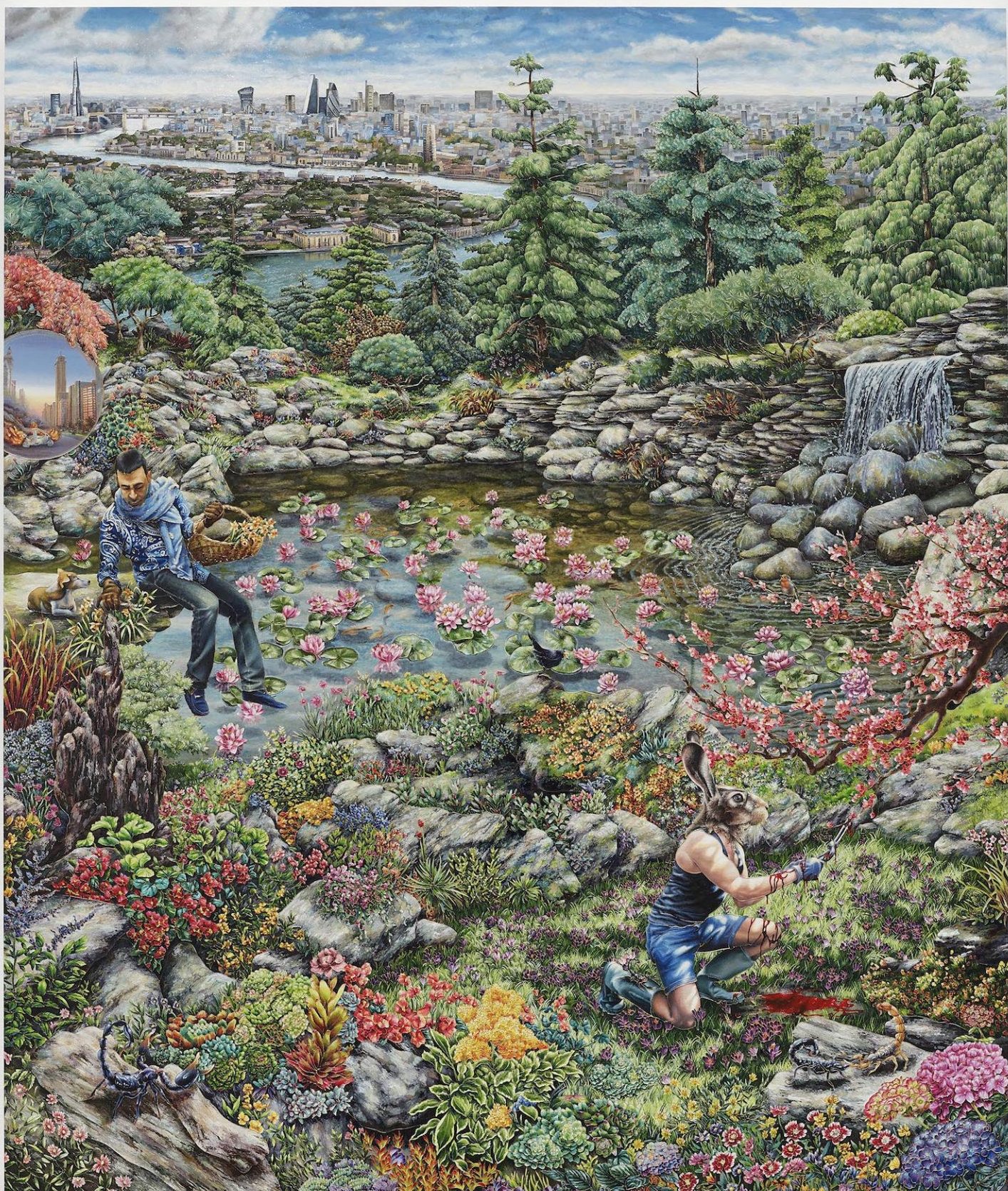

“My earliest memories of Kashmir are of my mother’s garden,” says London-based Indian artist Raqib Shaw, whose painstakingly intricate paintings are currently on show at Ca’ Pesaro, the International Gallery of Modern Art in Venice.

Among the Baroque marble-clad rooms of the Grand Canal-facing palazzo, Shaw’s fantastical scenes draw upon the Italian masterpieces of Tintoretto, Giorgione and Panini while still evoking his childhood in Kashmir. The setting for many of these new works, however, is his own garden in South London, a space outside his former sausage factory studio that he has converted into a magical urban oasis.

“Plants have been my friends since childhood and remain closest to me to this day,” says Shaw, who daily tends to his collection of Bonsai trees and used the 2020 lockdown to add a rockery water feature to his fairytale-like landscape. “The rockery plants are carefully coordinated with paintings in mind. Every bloom and its neighbour is placed to the best of my abilities.”

In his painting Agony in the garden (after Tintoretto) II, Shaw is accompanied by another figure (with the head of a hare) in tending to the flower-strewn rockery, the city stretching from the garden’s tree-lined border. In La Tempesta (after Giorgione), the world beyond Shaw’s verdant refuge is set aflame, the delicate and colourful blooms a striking contrast to the darkness and destruction.

“Every single plant and flower in La Tempesta has been taken from the garden,” notes Shaw. “It is a totally different experience to paint the flowers that I have cared for. They’re like tiny portraits of my children!”

“It is a totally different experience to paint the flowers that I have cared for. They’re like tiny portraits of my children!”

Shaw’s practice combining painting and planting has a rich history. “Monet is the artist-gardener par excellence,” said Ann Dumas when she curated Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse at the Royal Academy in 2016, a show that included work by fellow impressionists (who led the charge for painting nature en plein air at the turn of the century) as well as Kandinsky, Van Gogh and Klimt.

Like Shaw, Monet designed his own garden sanctuary. At his home in Giverny, Normandy, two sites were given over to his plant-based musings: a flower garden in front of the house as well as the Japanese-inspired water garden immortalised in so many of his paintings, and today a tourist attraction for 500,000 visitors each year.

More recently, Derek Jarman’s home in Dungeness, Kent, has also become a site of pilgrimage. Outside Prospect Cottage, the photogenic Victorian fisherman’s hut that the film-maker and gay-rights activist bought in 1987, the stark shingle landscape of his garden became a place of creative escape.

In the shadow of a nuclear power plant, hardy plants such as sea kale, lavender and poppies are punctuated with driftwood sculptures. It’s where he created films such as The Last of England (1987) and The Garden (1990). And where, having been diagnosed with HIV, he “cheated death hiding among the flowers and dancing with the bees”, wrote Howard Sooley, Jarman’s friend and the photographer he worked with on his book Derek Jarman’s Garden, published after his death in 1994.

“Outside Prospect Cottage, the stark shingle landscape of Derek Jarman’s garden became a place of creative escape”

Jarman’s legacy, however, lives on. Following 2020’s successful preservation campaign, which raised £3.5m, Prospect Cottage now enters a new chapter with Creative Folkestone looking to appoint a custodian for the property as we speak.

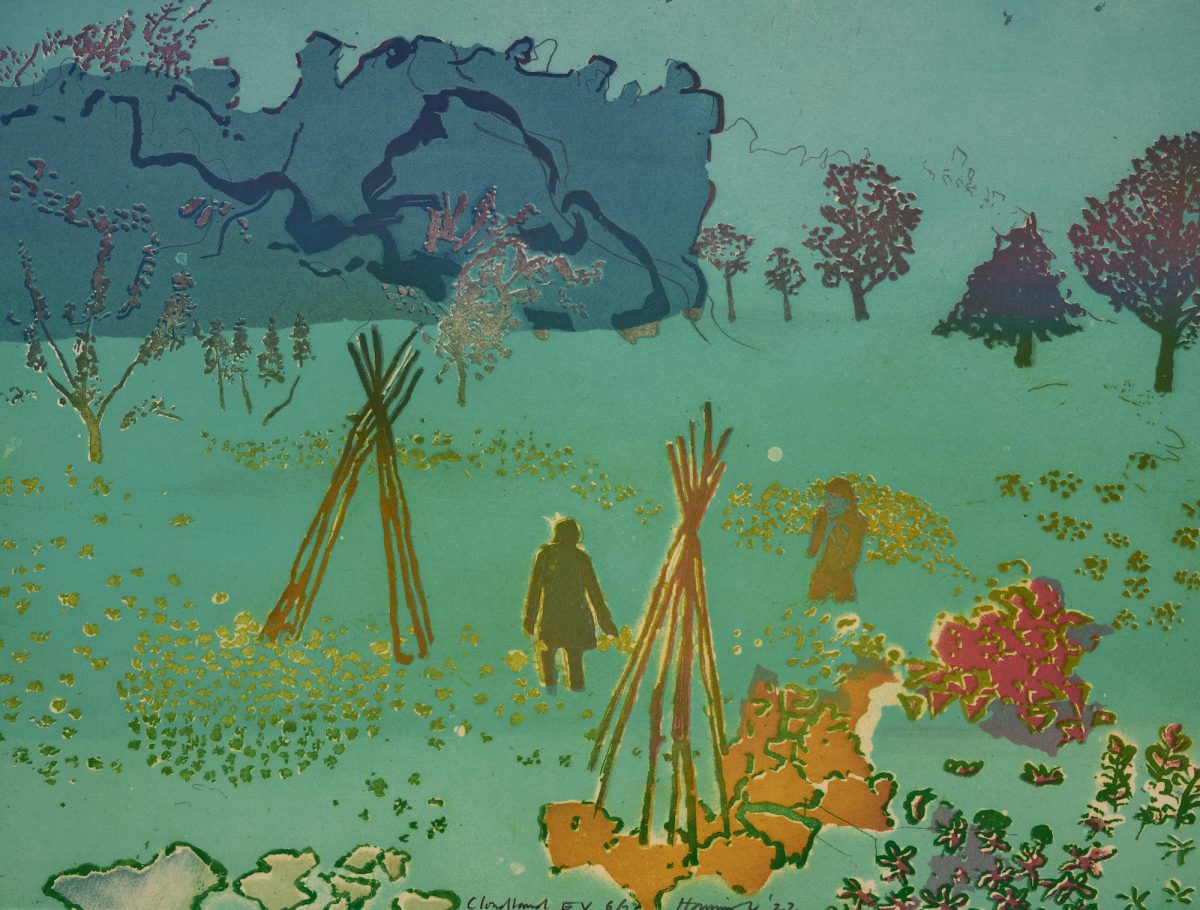

Meanwhile, the garden continues to be a creative source of inspiration for a wide variety of contemporary artists. At London’s Lyndsey Ingram gallery recently, the show of Tom Hammick’s work was titled My Sister’s Garden: spanning pen and ink drawings, etchings, paintings and luminous woodcut prints, the series, says Hammick, “celebrates the quiet, beautiful and slow aspects of life and reminds us that we do have a heaven on earth, if only we’d look after it. In gardening you see and feel that life can be regenerative.”

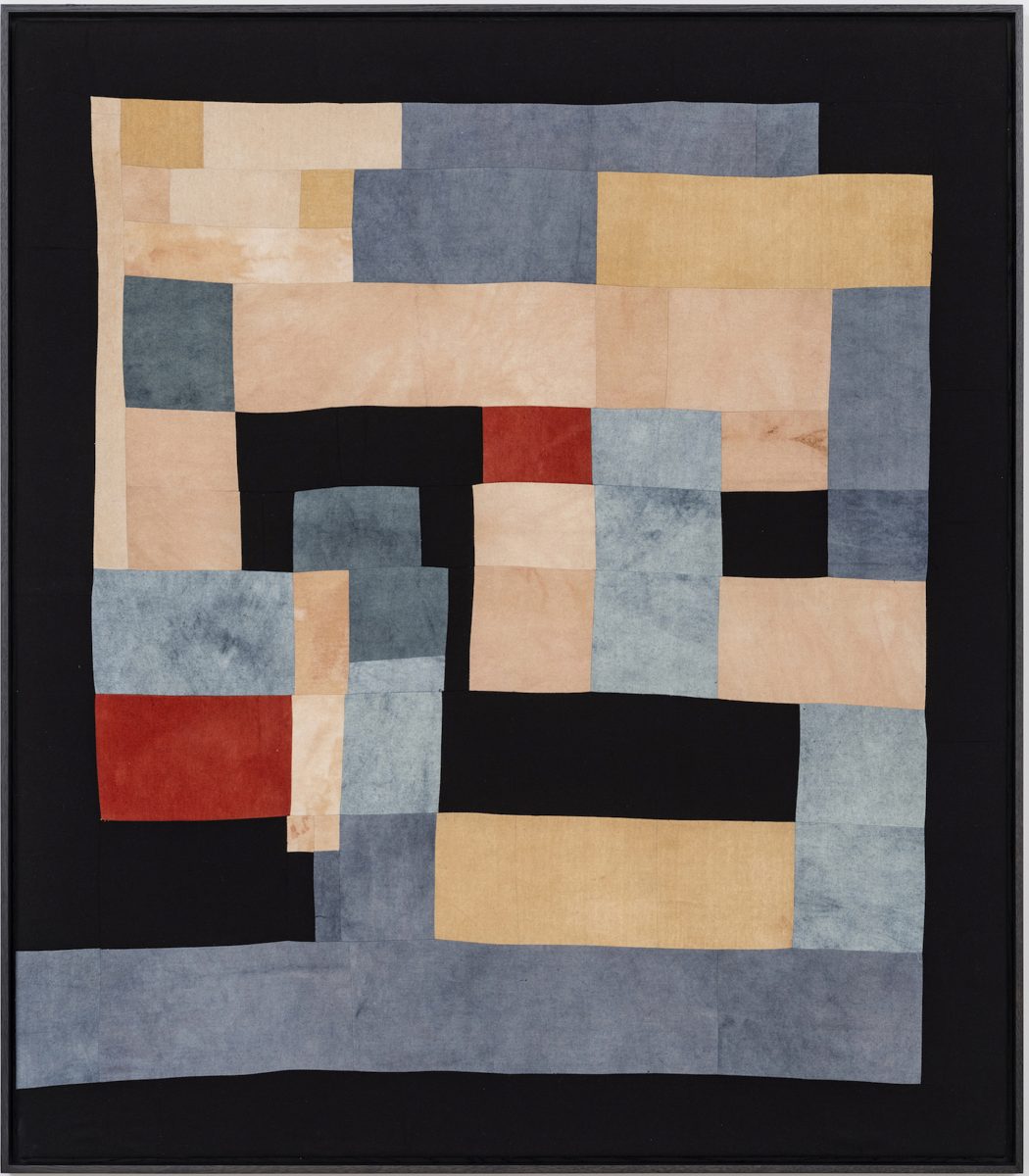

For French-Moroccan multidisciplinary artist Yto Barrada, gardening is used in a predominantly non-pictorial way. Her project The Dye Garden combines film, video, photography, sculpture and hand-dyed textiles created from plants grown in Tangier and worked into abstract canvases that reference Frank Stella’s Moroccan paintings as well as African abstraction. “This is the first year that we harvested a very ancient source for red dye, Madder (rubia tinctorum),” says Barrada. “I planted it four years ago. The roots we harvested this spring gave us a unique range of colours.”

Interested in historical narratives and geographic borders, Barrada began to think about plants in the context of her work after she met some flower hunters looking for irises in the Rif mountains in northern Morocco. The experience inspired the 2008 film The Botanist, and rekindled an interest in nature that began in her childhood. “Where I grew up, flowers and trees had names and lives,” she recalls. “We would wait for the seasons of the loquat or the pomegranate and stare at the striped caterpillars devouring nasturtiums.”

Now she is building a botanic forest garden and colour research centre in Tangier. They are part of The Mothership, a former farmhouse dedicated to “artistic exploration, especially research of indigenous traditions and natural dyes”, which is hosting its first residencies this spring. “We plan to be radical changemakers, leaning on the traditions of eco-feminism and Afro-futurism,” concludes Barrada.

The garden’s role in contemporary art can be experienced all over Britain this summer. On the Scottish Island of Bute, Tehran-born and Montreal-based Abbas Akhavan’s exhibition at neo-gothic mansion Mount Stuart includes an audio work to be experienced while walking among the grounds, past meandering streams to the vegetable gardens. Meanwhile in Cornwall’s Eden Project, Pollinator Pathmaker, a “living artwork” of 7,000 plants from 64 species by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg will spring into life later this month.

“I wondered what a garden looks like from the perspective of its real users: pollinators. They see the world differently to us”

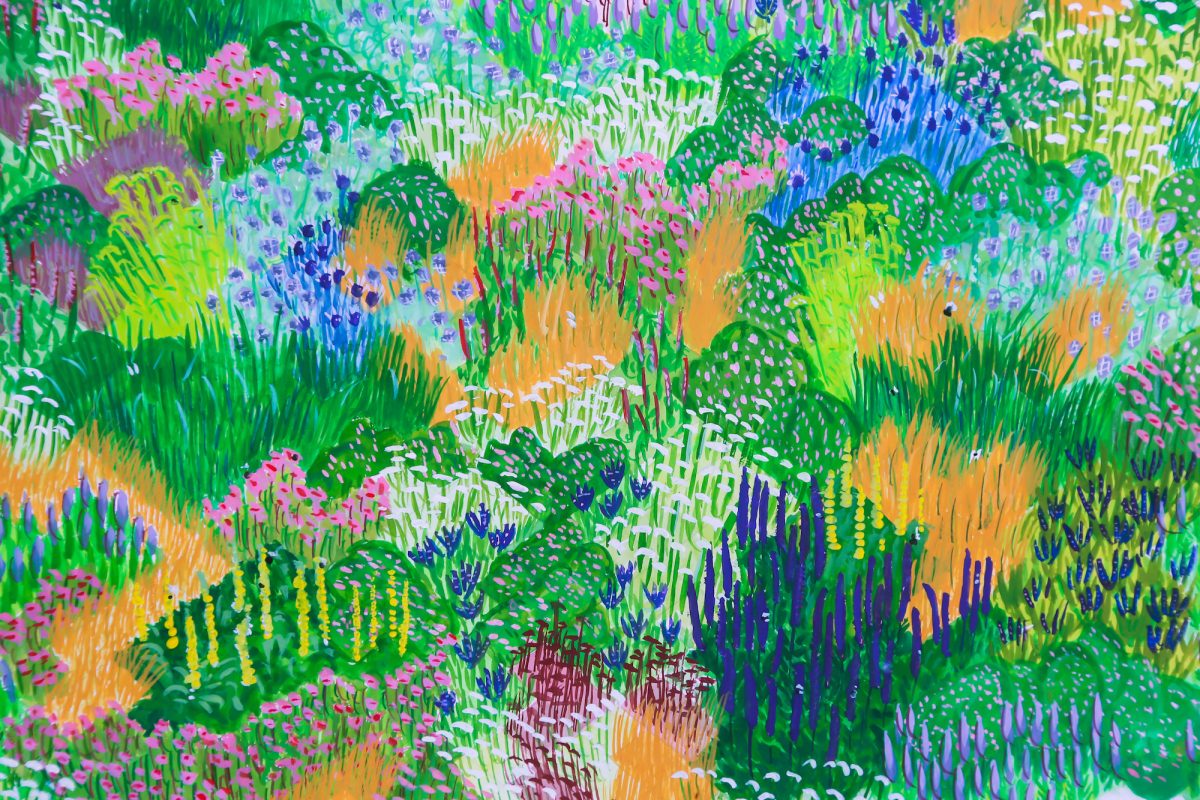

“I was commissioned to make an artwork about pollinators, to bring attention to the jeopardy they face,” says Ginsberg, an artist examining our relationships with nature and technology. “But I suggested I make an artwork for pollinators. I wondered what a garden looks like from the perspective of its real users: pollinators. They see the world differently to us, and to each other: bees can’t see red, for example, but can see UV, while butterflies can generally sense red, green, blue and UV.”

- Left: Preparatory sketch by the artist, 2020. © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg; Right: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg at Eden Project, 2021. Photo: Steve Tanner. Courtesy Eden Project

The planting scheme was created by an algorithm Ginsberg developed. “The algorithm selects and arranges plants for me to meet pollinators’ needs,” she explains, adding: “I can’t wait to see what the insect audience makes of the artworks.” Further editions will be planted in London’s Hyde Park as well as in Berlin, while the Pollinator Pathmaker website can be used to plan your own pollinator garden.

It’s a call to action that is echoed by London gallery Sapling, which on May 6 launched a limited-edition of British wildflower seed packets designed by Gilbert and George. Produced in partnership with contemporary artist Sam Harris, the packaging depicts the iconic artist duo as leaf-like creatures, alongside the words: “Gilbert & George say Spread your Seed”. It’s a tongue-in-cheek yet timely reminder of the garden’s continuing relevance, as both a site of personal pleasure and an act of ecological importance.

Victoria Woodcock is a freelance journalist and contributing editor at How To Spend It

Raqib Shaw: Palazzo della Memoria is at Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Ca’ Pesaro, Galleria internazionale d’arte moderna until 25 September 2022