For most women, life can be punctuated by a preoccupation with breasts. You worry about whether they will arrive as a teenager, whether they are too big, small, symmetrical or otherwise. Then you might become concerned with how much cleavage is “appropriate” for a variety of situations, from the office to the beach, or indeed the pavement, where any sign of bodily existence can result in unwanted catcalling as you walk from A to B. Later on in life the bounds of how, when and where one is allowed to carry out the primary function of breastfeeding will be avidly discussed by anyone and everyone, before concerns of sagging—of losing what is deemed a seductive asset—might creep in.

Thinking abstractly, the fact that two mounds of flesh, complete with nipples that are a genderless feature of the human body, can be subject to such extreme societal censorship, exploitation and scrutiny is confounding. Instagram’s hazy yet draconian rules around showing boobs led to the Free the Nipple movement; the presence of bare breasts in a national UK newspaper was hotly debated for years; and unchecked comments concerning the size, shape and presence of cleavage can make plenty feel as if their body has become public property. As a teenager, I distinctly remember the horrible feeling of someone “announcing” my burgeoning breasts, as if their presence suddenly made me sexually available.

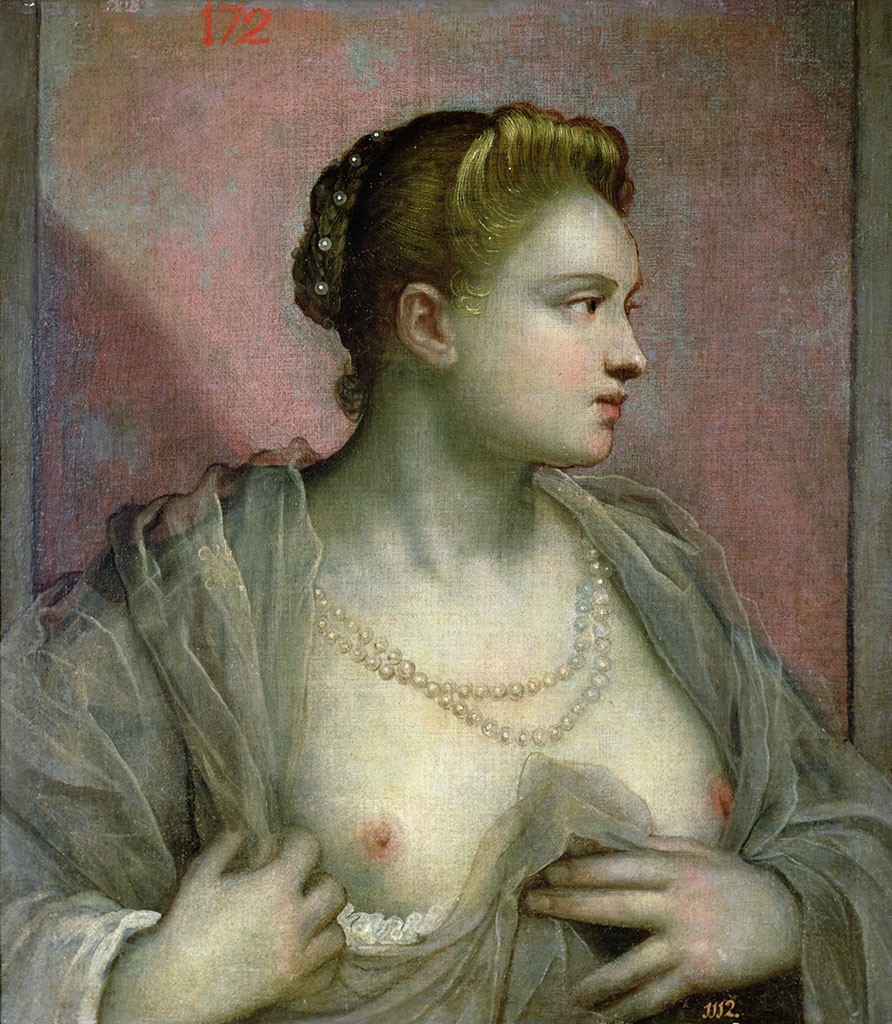

- Left: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Venus Verticordia, 1868; Right: Tintoretto, Portrait of a Woman Revealing Her Breasts

In terms of Western art history, the exposure of the bosom is most often presented as an act of sensual behaviour, bar the nurturing image of the Virgin Mary. Breasts are the apex of the male gaze, designed to be voraciously consumed as a symbol of traditional femininity, eroticism and naked vulnerability. Take, for example, Tintoretto’s Lady Revealing Her Breast (1580-90) which depicts a high-ranking courtesan who, according to the Museo del Prado’s website, “so generously offers the viewer” her nudity (groan); Rubens’s painting Helena Fourment in a Fur Robe (1636-8), in which his teenage wife is shown barely covering her impossibly pert breasts; or Rossetti’s Venus Verticordia (1868), where the woman points to her nudity with an arrow, thus defying Victorian England’s puritanical values in favour of lust and longing.

More recent outlooks concerning the way we view breasts can, to an extent, signifying prevailing sociopolitical attitudes. Much like fashion, where the rising hemlines of the 1960s signified a new, affluent style of living (people were suddenly willing to pay more for less fabric following dramatic post-war austerity) the way we present our boobs can be a sign of the times. The most obvious example, of course, would be the apocryphal tale of feminist activists “burning their bras” at the Miss America pageant over fifty years ago. Despite the fact that women actually threw their undergarments into a “freedom trash can”, the idea of going out without wearing something to harness your tits has become synonymous with activism and liberation.

“Contemporary artists have long challenged the way we visualize breasts as a way of combating society’s expectations”

Femen takes this notion to the extreme. By going topless as a form of protest the group often grab headlines for all the wrong reasons in certain sections of the media (particularly as many of the members fit a stringent beauty ideal), but their message is still heard. They have reclaimed their bodies, which are already considered public by so many, as a site of discourse and defiance.

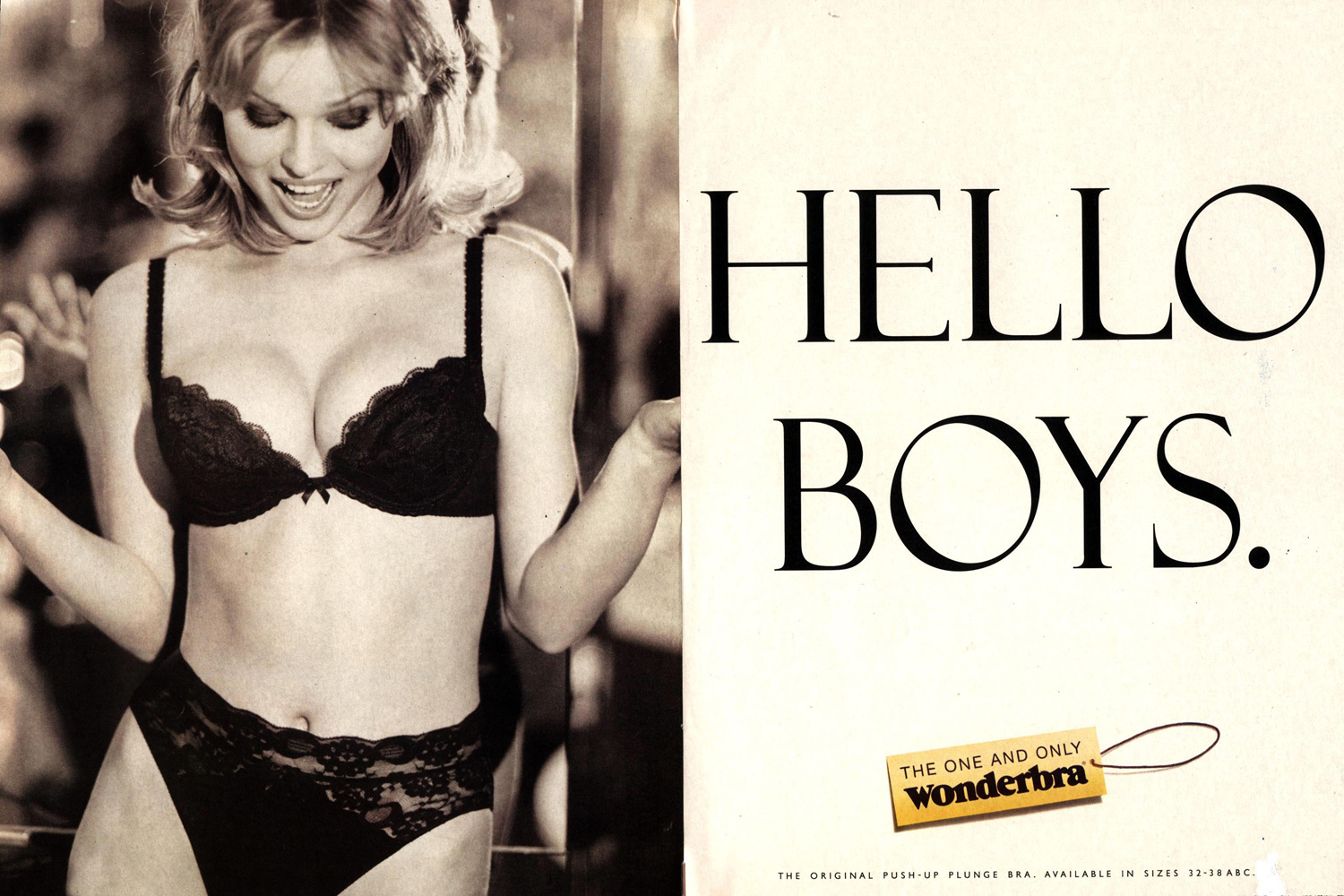

It is also fair to say that the pendulum has firmly swung away from the fashions that defined the nineties and early noughties, where padded décolletage was held erect by what amounted to miniature scaffolding. In an age where lads’ mags reigned supreme and the Wonderbra advert caused car accidents, it made sense that most women felt pressured to bring their breasts up front and centre. While brands like Agent Provocateur and Victoria’s Secret cashed in on this culture, most of their offerings now seem relatively staid and outdated. I worked for two years at the former, and the fact that I spent my working life manipulating my body into Jessica Rabbit proportions and syphoning others into the same mould seems laughable now.

Now, as issues of body image, fatphobia and inclusivity are becoming more widely discussed—particularly in fashion—it makes sense that discussions around breasts have become more nuanced. Writer Chidera Eggerue has made headlines with her #SaggyBoobsMatter initiative, while activist Ericka Hart—who is a breast cancer survivor and underwent a double mastectomy—has challenged perceptions of identity, race, sexuality and what society decides a body should look like. Ethical, sustainable brands have also begun to pop up, offering comfortable alternatives to the underwear dig-in, and it’s telling that Rihanna’s recent lingerie venture includes a high percentage of crop tops, soft cup and bralette models.

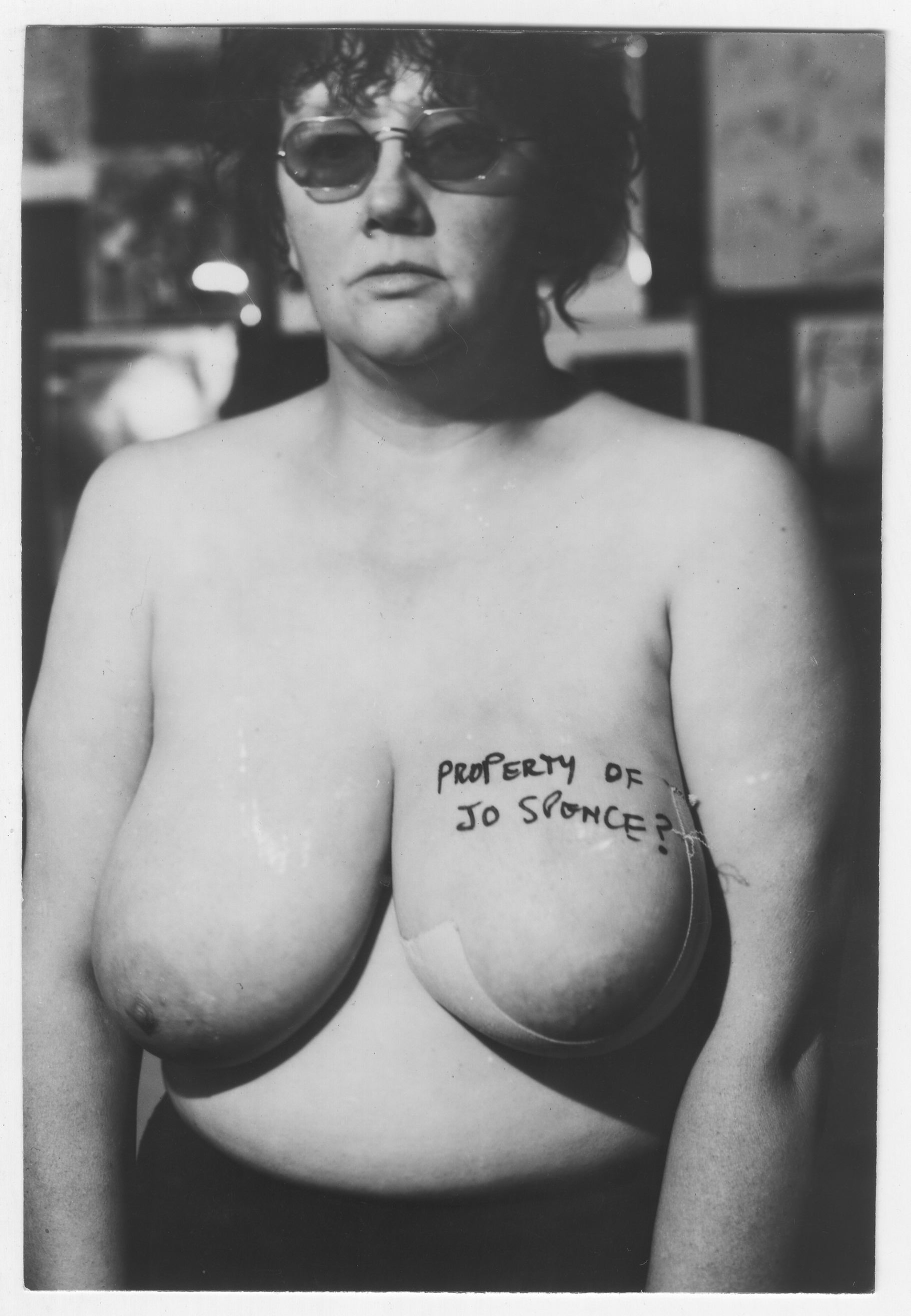

Although fashion might follow an unfixed curve, contemporary artists have long challenged the way we visualize breasts as a way of combating society’s expectations. Take Jo Spence, whose powerful photo-documentation of her cancer treatment is currently on show at the Wellcome Collection. Her candid images question how we identify with illness and allow the photographer to reclaim her body at a time when medical treatment can alienate and dehumanize a patient.

Jenny Saville’s astonishing, fleshy paintings also belie a fascination with women that is not traditionally the artist’s subject. They are presented with ample folds of flesh, often with breasts that appear flattened, squashed or hanging against the curves of the body in a satisfyingly naturalistic way. There certainly seems to be a market for it—the painting Propped recently made Saville the world’s most expensive living female artist.

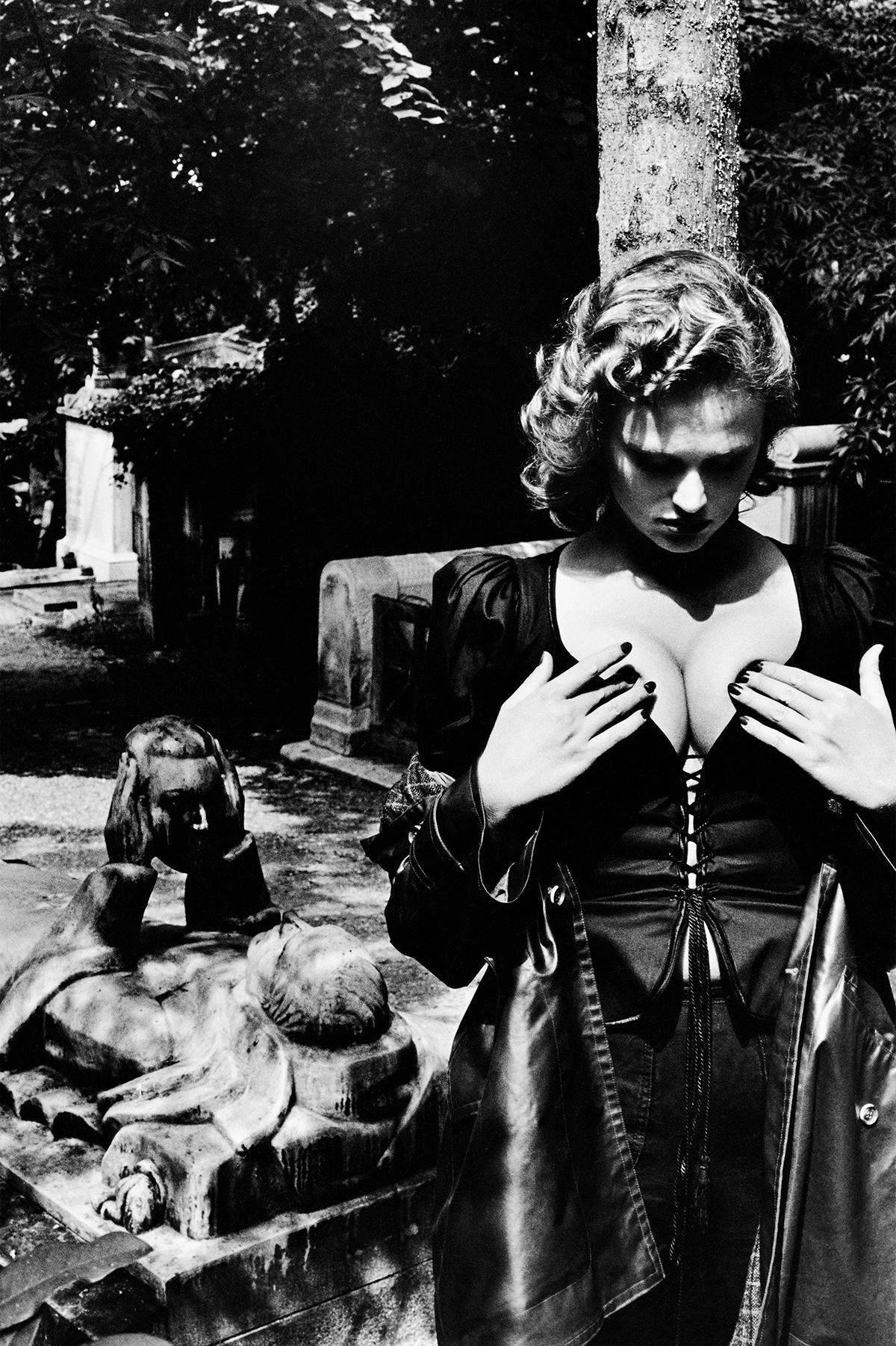

Alternately, the familiar, bionic version of breasts has also been used by Victoria Sin in order to interrogate perceived notions of femininity by parodying the female form in the extreme (see their work on show at the Hayward Gallery’s Kiss My Genders exhibition). Their gigantic silicone boobs, tiny cinched waist and glamorous bouffant emulate Hollywood stars and pinups, but actively subvert this ideal in a manner that is a world away from the complicit, fetishized images created by the likes of Helmut Newton or John Currin.

In Sin’s performance work, The Sky As an Image, an Image As a Net, they speak about their arousal and confusion around wearing these breasts, and attempt to unravel what exactly these strange objects signify. For many of us, that conflict will be familiar. In a world where our value is so often placed on the aesthetics of the body, breasts are one of the most obvious signifiers concerning our worth and even our own desire. Whether you decide to hoick your tits into gravity-defying positions or let you flesh fly free, your body will probably still be held to unwanted scrutiny, and we still have a long way to go before that changes.