Emerging in the 1980s when figurative painting had its second coming in New York, Carroll Dunham has delivered a diligent body of work, characterized by an instantly-recognizable painterly technique. Working from his Connecticut studio where he lives with his partner and fellow artist Laurie Simmons, Dunham paints nudes unlike any other artist, detaching his subjects from psychological undertones that art history has traditionally ascribed for stripped bodies. At sixty-eight, the artist is humorous and earnest while talking about his recent body of work—shown earlier this year at Gladstone Gallery—which veers away from his long-term interest in the female figure in favour of robust depictions of men wrestling.

What attracted you to painting images of men wrestling?

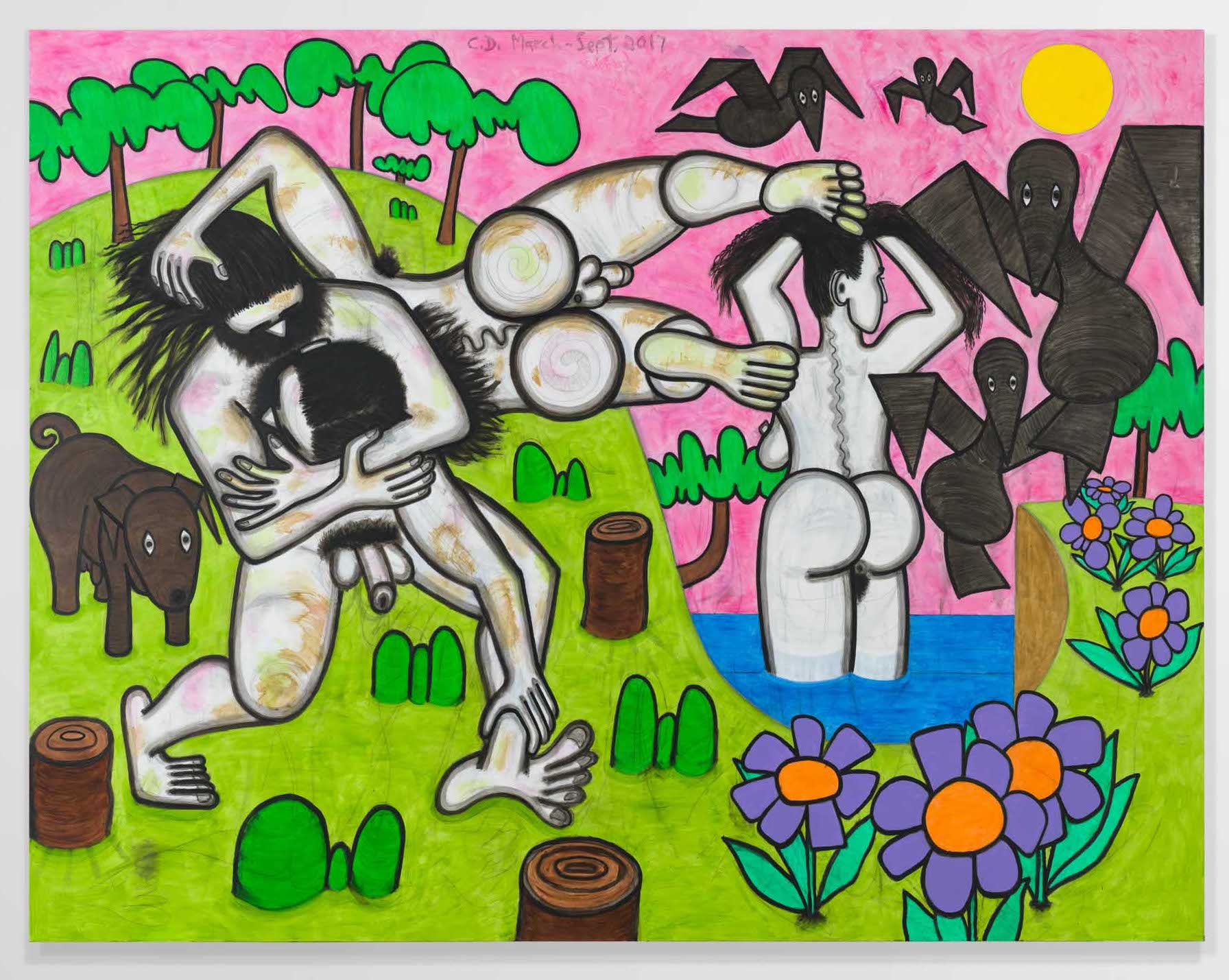

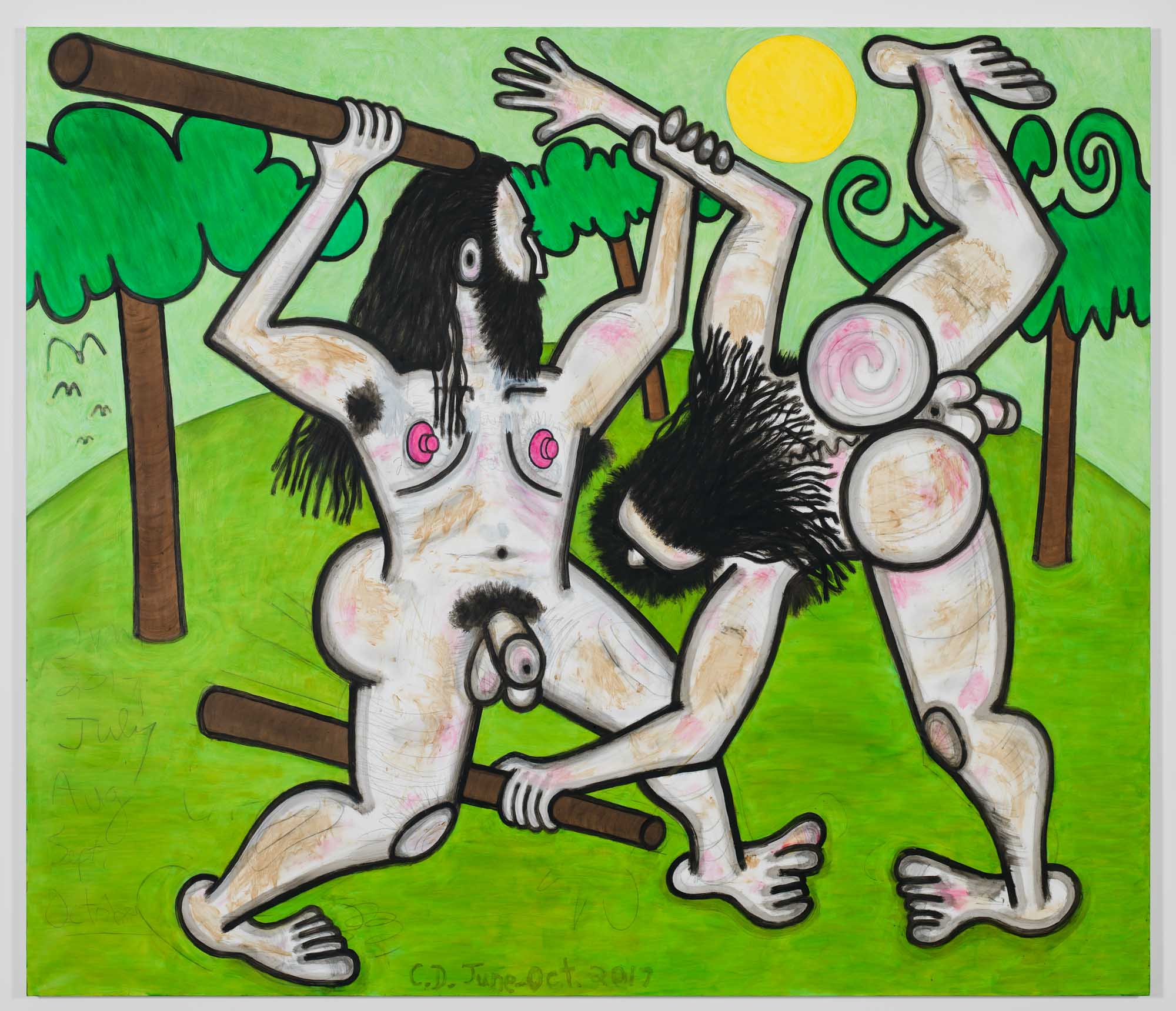

I always wanted to bring the subject matter to men at some point. Men wrestling introduced a male equivalent of my women and presented a more complex narrative with the urge to put multiple figures into the painting. The topic’s art historical connotations, similarly to my Bathers series, connects my work to an older tradition in art.

The subject matter offers plenty of opportunity for painterly experimentation, with depictions of the human body in challenging contortions and positions.

My work demonstrates that I have no training or background in figure drawing. I’m trying to achieve a minimal level of acceptability of what you’re looking at. The opportunity to ignore the reality and make something purely interesting as pictorial construction attracts me. When I started making drawings in that sense, they ended up looking very crude, but I immediately realized that they were compositional possibilities.

Your decision to depict men in their most brutal state coincides with the #MeToo movement and discussions around toxic masculinity. How do you see the paintings through that lens?

My own masculinity has been fairly toxic to me for a long time [laughs]. Of course, I am aware of the cultural upheaval: I have two daughters and my wife has been very much involved with these issues; I feel I have been fairly schooled. However, I don’t really see my paintings through the lens you are referring to. If I chose to look at them from a psychological angle, which I don’t so much, I’d see self-criticism and self-representation rather than looking outside.

“I have two daughters and my wife has been very much involved with these issues; I feel I have been fairly schooled”

The paintings contain both defeat and victory. The figures are captured in glorious or fallen states. Speaking of male vulnerability, how did you build that comparison within the same narrative?

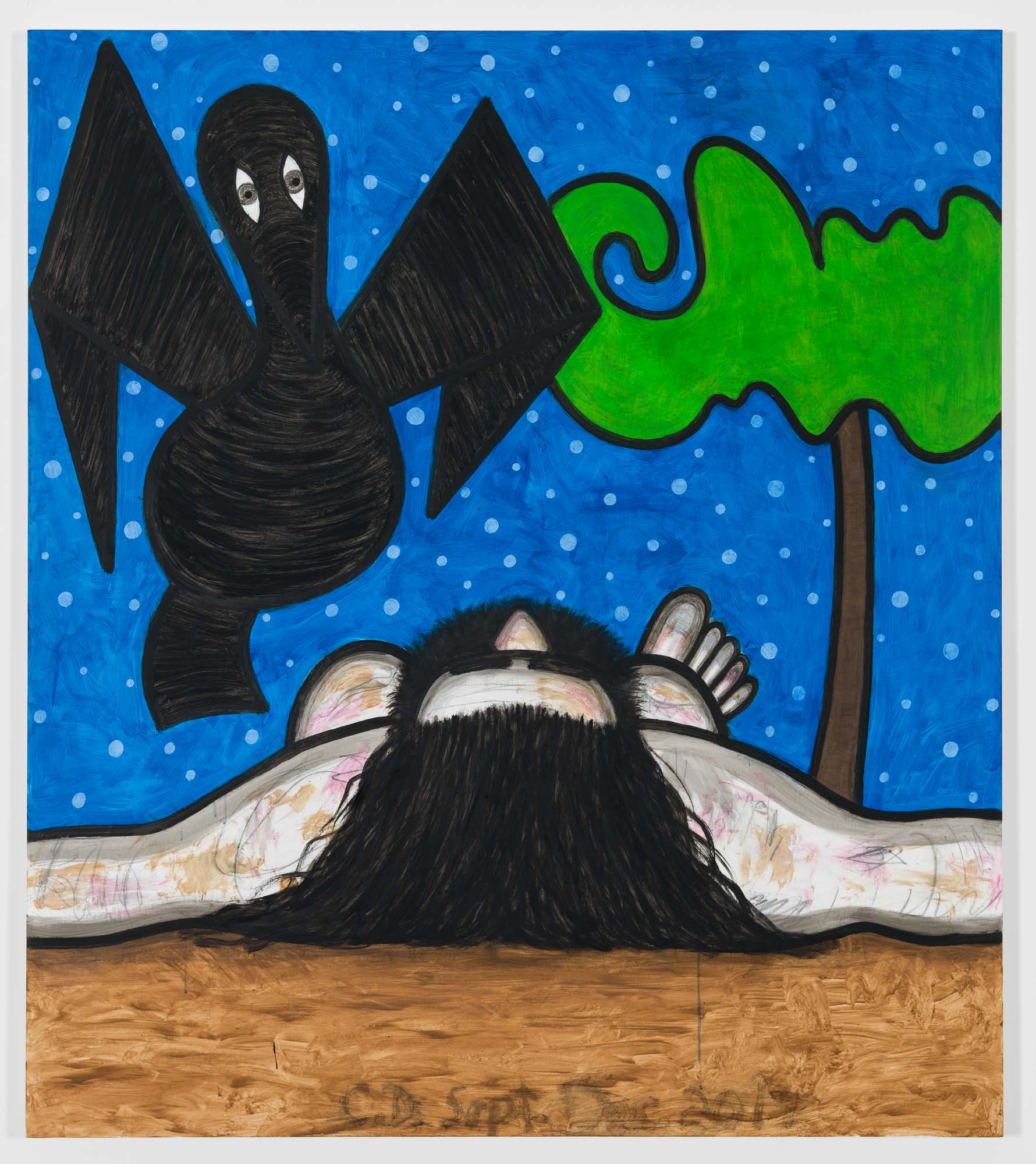

I invest a good amount of thinking to figure out what looks right without being coy, which started out as a formalist art problem I proposed to myself. A situation where two human beings interact in a picture begs for narrative interpretation, but the way each of these things exists either on its own terms or in groups is a formal problem. I figured out an interesting way to draw a male body lying on the ground, either viewed from the top or the bottom. At first sight, this is a picture of a corpse; he’s either asleep or dead. That leads to a chain of associations about what the painting might convey in addition to a vocabulary evolving from my earlier paintings of women bathing.

History has seen men wrestle over the centuries from ancient Rome to present Turkey. The paintings have a timeless aura—they appear to be stripped from history or geography. How do you stay ambiguous with time and place?

This is a completely conscious choice. There is no room for clothing, architecture or cultural touchstones in my way of thinking. Before adopting this artistic concern, my earlier work had references to gender signifiers to glamorize abstract forms, but this doesn’t fit into the current work. If there is a time or place the work belongs to, it’s either a long time ago or a distant future, where there is no resemblance to the present.

“Men standing in endless mud-like brown instead of blue conveys weird possibilities in terms of the narrative”

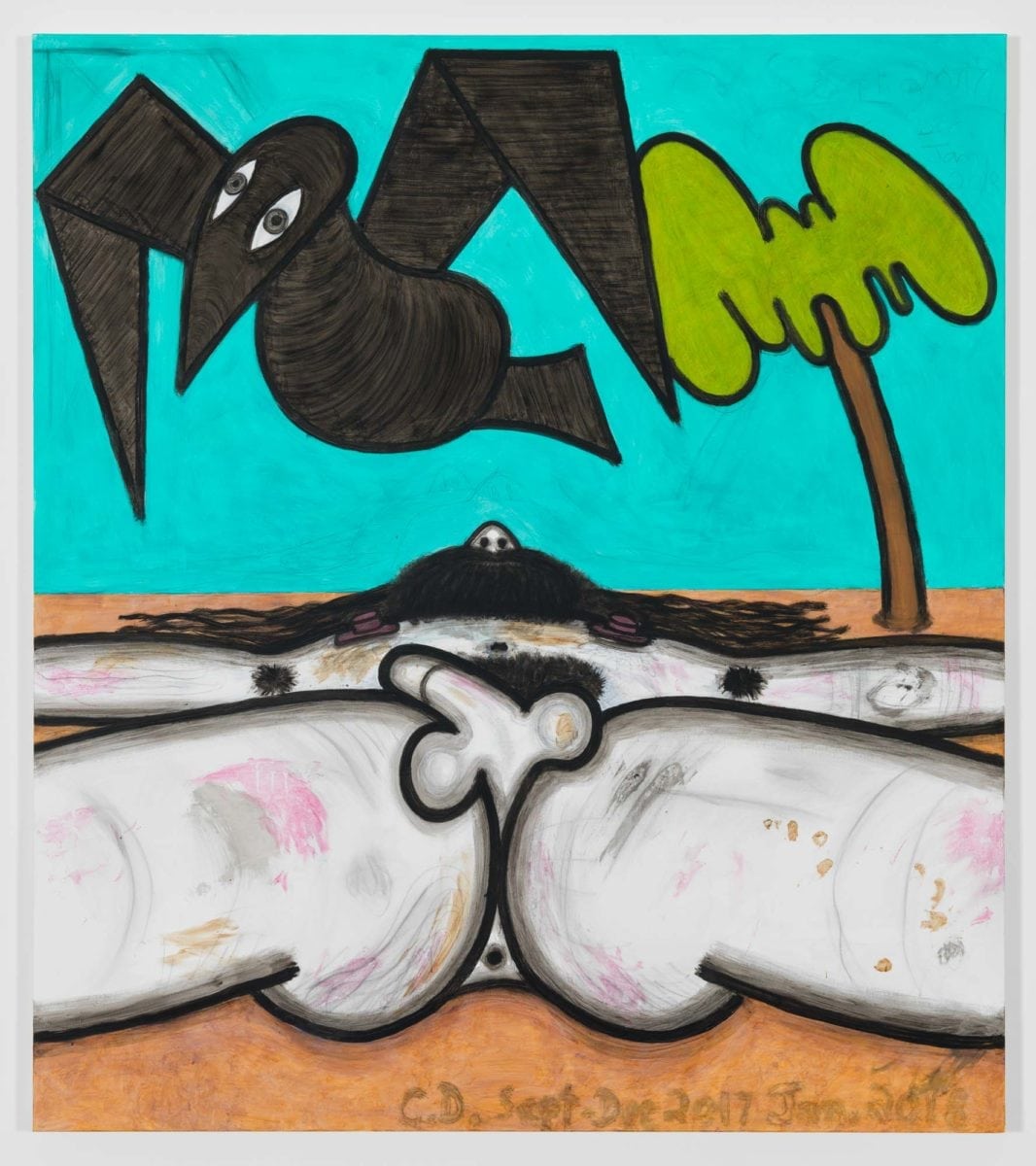

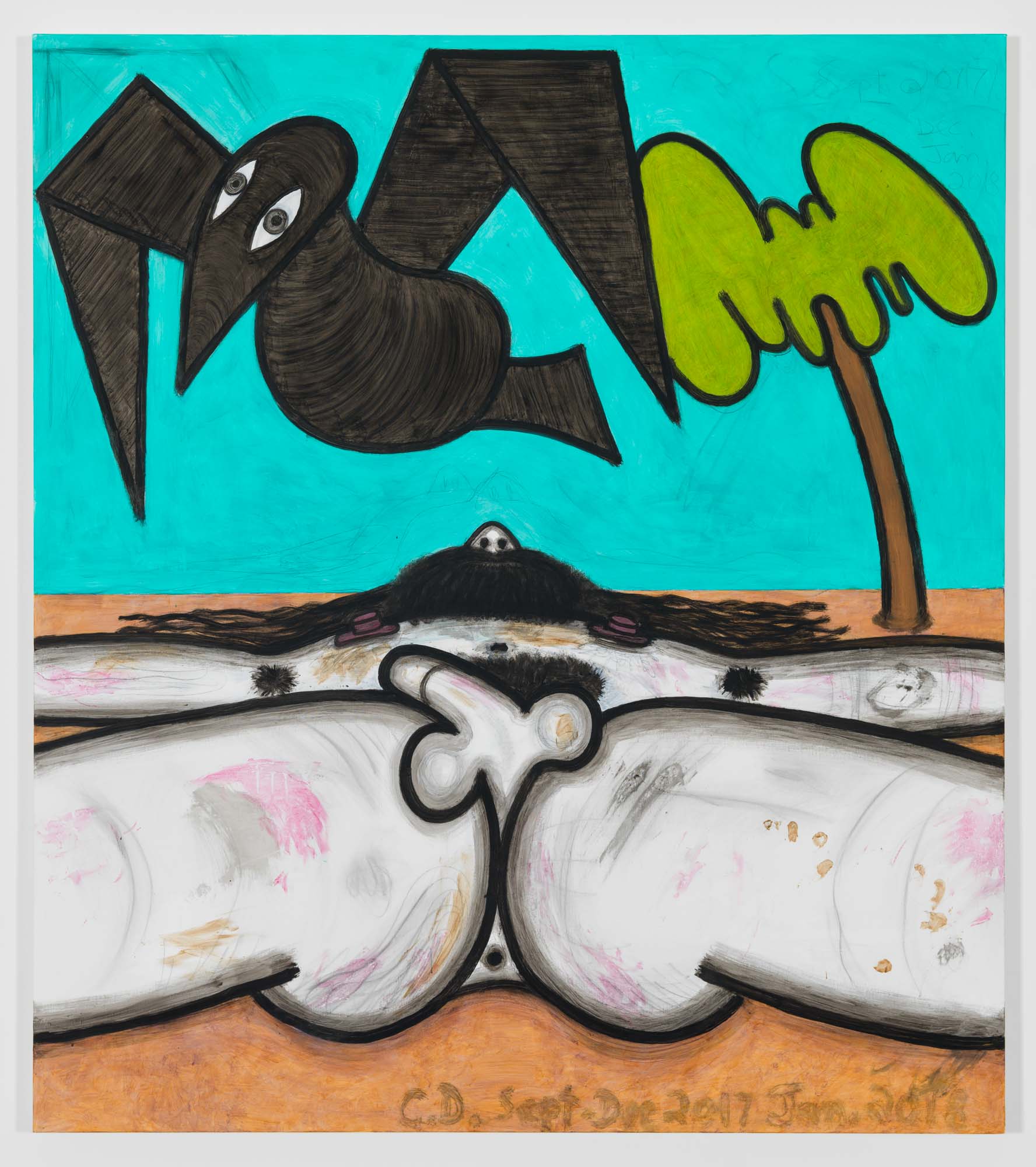

The black vulture figure haunts the paintings like a ghost, bringing a critical eye in the way the Greek chorus does. It doesn’t fit any typical depiction of the animal, which is a contrast to the representations of other figures.

I could create something more “birdlike”, but when painted in a certain way these four shapes stuck together are impossible not to see as birds. This Frankenstein

-type character gains an inner life and awareness, especially after drawing the eyes. I don’t want the human beings to have particular features beyond the representation of their relentless activities since I don’t want to address culturally topical issues. The animals somehow become the vehicle for animated quality. These birds are ridiculously simplified, yet they allow for another level of commentary within the picture.

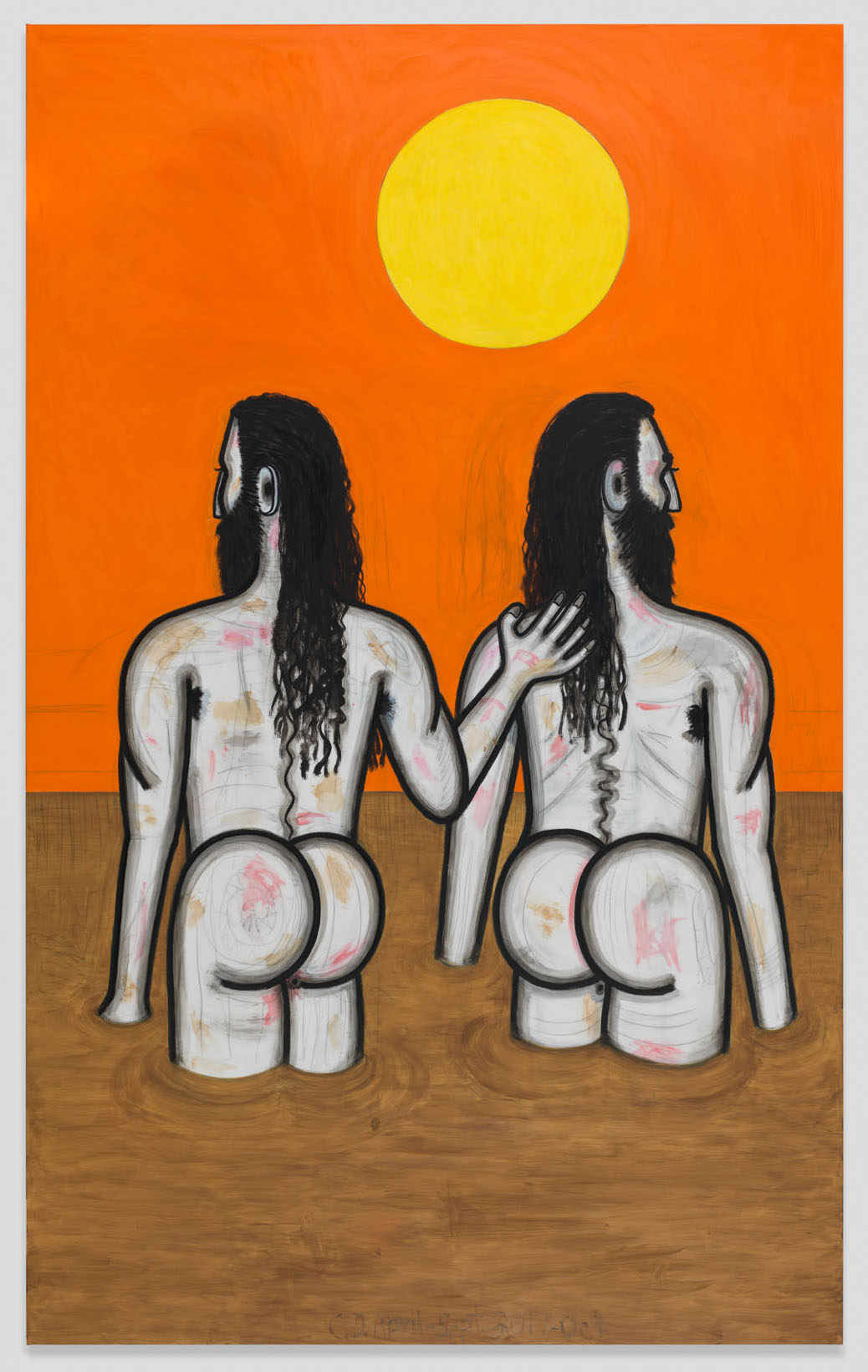

There is a contrast between tenderness and brutality. In one painting, two men watch the sunset while one keeps his hand on the back of the other; in another painting, we witness a barbaric fight between potentially the same duo. How do you build narratives with intricate contrasts?

I drew a wrestler inside water for a pencil drawing study, but later added a companion to see how they would look at a moment of tenderness and break from all the bullshit they are constantly dealing with. I immediately envisioned that this tall, thin painting had something to do with water. When I was stretching the canvas in my studio, I started thinking about colour and having the bottom of the painting brown instead of blue. Men standing in endless mud-like brown instead of blue conveys weird possibilities in terms of the narrative.

Do you find there is a difference in depicting the male or female physique and genitalia?

I have to make my intended representations plausible without getting too concerned about signifying actual human anatomy. The level of discomfort my paintings generate has always surprised me. The reaction they receive from certain people is baffling. My depiction of a vagina is pink lips surrounded by black lines, but nothing more explicit. Frontal male nudity is still challenging to put on TV or film and I think the same thing is still true in painting. My work confronts the viewer with the idea of what they are looking at, but not with the actual image.

You can read more about Carroll Dunham in Ariela Gittlen’s issue 24 Encounter with the artist

BUY ISSUE 24