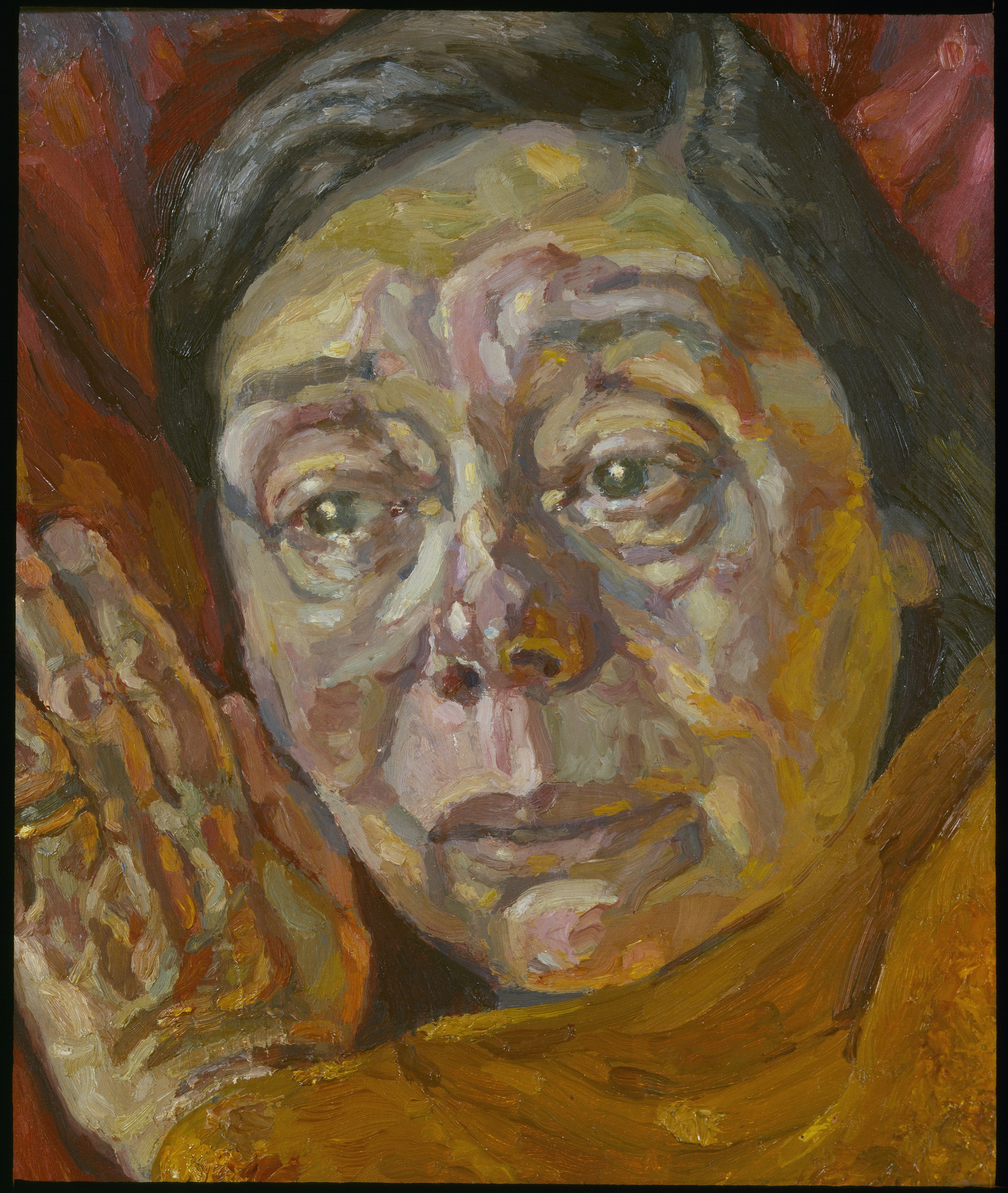

Since the late 1970s, Celia Paul (b.1959) has been producing technically brilliant and intimate paintings of the people close to her. At once numinous and gamy, they usually exude a sort of old master halo. Sir Lawrence Gowing, her mentor at the Slade and one of the finest art historians to have taken up a pen, claimed that her early work Family Group (1980) “was as good as a Gwen John, and the best painting ever done by a Slade student”. It inspired Lucian Freud, her lover, to begin a similar work, though his finished canvas Large Interior W11 (After Watteau) deflects the anxiety of influence in a different direction.

The ten-year relationship with Freud takes up a large part of Paul’s memoir Self-Portrait, as it does the journalistic airspace around her. A quick google will reveal that editors have thought it prudent to give the dead male artist equal billing on her headlines in a hope to drive traffic. Or just out of a sort of habit. The dialogue around classing women artists as the muses of the more famous men simply because of their relative standing has been buzzing for decades. But right now—especially in the context of today, when women are digitally yoked to their male lovers even as they are trying to break free of that collocation—it is getting specific attention.

At the end of October, Guardian journalist Rhiannon Lucy Coslett wrote a twitter thread in response to the plugging of the touring Dora Maar retrospective: “I really feel very strongly (and see also Lee Krasner) that the only way women artists can begin to be respected and appreciated on their own merit is to stop using the names of men they slept with in headlines for articles about them […] by repeatedly invoking the men they slept with you are in a sense minimising them again while claiming to righteously raise them up”.

“The dialogue around classing women artists as the muses of the more famous men simply because of their relative standing has been buzzing for decades”

For this reason, writing about Self-Portrait presents a double-bind. How best to centre Paul without Freud, when the formative years here depicted are centred around him? When the memoir itself gives over at least two thirds to the complex relationship between the two artists? The answer is that such a separation is never the intention. In writing Self-Portrait, Paul has replaced an old portrait of Freud she once attempted but painted over with a written one that also reenacts her own work, Painter and Model (2012). Begun immediately after the death of Freud, it shows Paul alone. This work alludes to and takes over the narrative from a much earlier Freud work of the same title, in which he painted her for the last time. There Paul paints a male friend. She is in a paint-coated smock, similar to the one in the later work, and the man is nude. We tunnel backwards through references in which the network of influence and sharing is indivisible.

They met when Paul “was a teenager” and Freud was fifty-five. He walked into her class at the Slade and immediately invited her to his house, where he made an advance. “The Tuesday following my first encounter with Lucian I decided not to go into the Slade. I was afraid of him and reluctant to see him again.” On her second visit to his house, he dragged her onto the floor in his hallway not heeding her unresponsiveness, and stopped kissing her only when the doorbell rang. He had forgotten he already had a “visitor” coming; Paul was sent away, and passed the woman who was Freud’s previously arranged assignation on the stairs.

- Celia Paul, Shoreline, 2015-2016. Courtesy Jonathan Cape

From a distance Paul is aware of her own vulnerability in these situations, and the power imbalance to which her younger self was susceptible. In parallel, Paul quotes her journals and letters of the time in which she is constantly “melting in gladness” at a touch in the back of a car. The journals make for set pieces stuffed with famous names; the sort of thing many a book chronicling the milieu of the time has thrived upon. Here they have a bildungsroman poignance and tragicomedy that punctures the pretensions of the male celebrities depicted, just as it frames their genteel callousness.

From her 1978 journal: “We arrive at Auerbach’s studio. Lucian gets out of the car and goes through the gate and follows the sign ‘To the Studios’ down a flight of steps. He enters the studio and closes the door behind him […] We are joined in the cocktail bar by Auerbach and the woman. No introductions, or perhaps Lucian says ‘This is Celia Paul’ and Auerbach is looking the other way […] The woman doesn’t say a word and nor do I. We do not say a word to each other, either. Two dynamic scintillating men and two silent bewildered and embarrassed women sitting eating olives.” Freud’s daughter Bella arrives—“She must be about my own age”—and he doesn’t take his hands off Paul: “She didn’t take any notice of me, nor was she at all suspicious of me.”

“As a depiction of difficult relationships between artists—fruitful and terrifying—it is important and necessary”

Freud’s general sort of selfish inappropriateness, which has for at least half of his reception been forgiven as bohemian—a sort of refined, sophisticated lack of care for boundaries—arrives refreshingly stripped of perceived glamour. Indeed, when Paul relays how her mother doesn’t approve of her relationship, “I couldn’t justify myself to her, because I too felt that my growing love for Lucian was more like a sickness”

There are many books about experiencing an artist’s gaze. Even some about experiencing Lucian Freud’s gaze, such as Martin Gayford’s Man with a Blue Scarf. Paul gives one of the most powerful renderings of sitting for someone, and of having others sit for you, imaginable. “When [Freud] came to painting my breasts, I felt his scrutiny intensify. I felt exposed and hated the feeling. I cried throughout these sessions”; “He didn’t like me going off into a world of my own. He wanted active participation. He would talk and ask me questions while he painted. He liked to watch his sitters in movement […] I would have preferred to think my own thoughts and be peaceful, but he wasn’t having any of that!”

None of this seems related with complaint, rather Paul is painting the process for us in its flesh-tones and visceral purples. Indeed we hear from Paul herself that she wasn’t dissimilar with her own sitters, or at least any less exacting or personally reductive—if free of the considerable power imbalance experienced by a young student sitting for an old grandee who is also her lover. She paints her mother naked, shouts at her and makes her cry; her mother accuses her of “treating her like an object”. An Italian life model does and says the same. As we read, we feel that Freud’s own self-containedness moving into narcissism—he drew artistic energy from “his own complicated love-life and the undercurrent of jealousy”—has been placed on the canvas as a lowlight for Paul’s own approach: her clinical look at personal material and her need for solitude, and the unapologetic right to wholly compartmentalize her life; the rich austerity that is imaginative space.

Being brought up in a religious community in Devon and sent to a boarding school meant Paul never got any privacy. “Painting became my way of guarding and controlling my inner life.” At school she met her first muse, a girl called Linda Brandon whose ability to paint from memory she envied. Their friendship and competition involved locking each other out of the school art room and getting up early to paint in secret, without the other knowing. Of course, they always knew. Paul painted frantically at home; Linda’s parents worried about her and pulled her out of the school. When Paul went to art college at sixteen, having honed herself into some sort of wunderkind through the intense competition with her friend, “I preferred to be secreted in my basement room, far away from the other students. I cooked my meals on a Baby Belling because […] I needed to be alone.” There are points reading this book where you long for more of Paul “alone”. But as a depiction of difficult relationships between artists—fruitful and terrifying—it is important and necessary.