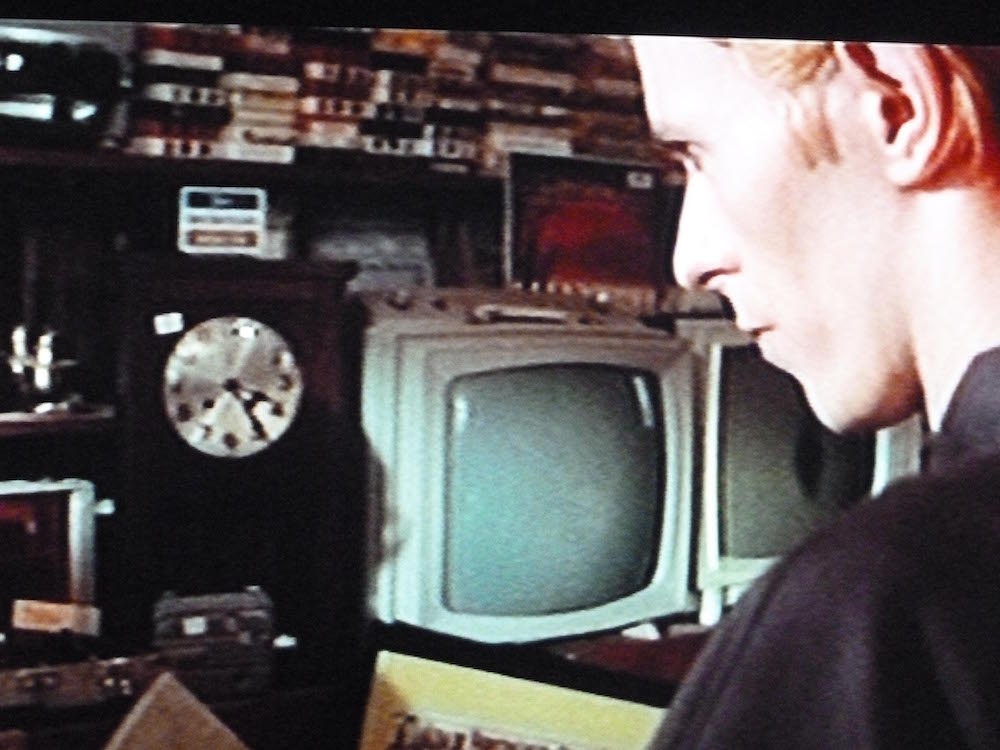

Bowie has personal significance for Petit, who worked with the icon on two tracks for his film Radio On (1979), in which one scene pays homage to The Man Who Fell To Earth. In What’s Missing, Is Where Love Has Gone is co-curated by Louisa Elderton & Jelena Seng and takes its cue from a particular scene from the 1976 film in which a mass of television screens are watched by Bowie, an early signal perhaps, of the proceeding explosion of images on our computer screens.

We spoke with the writer and director.

Can you tell me a bit about In What’s Missing, Is Where Love Has Gone?

At some point in the last ten, fifteen years the image bank exploded and we now live in this huge electromagnetic slum of visual glut. Life is a series of rewinds and fast-forwards and sometimes you see things in a way which you may not have noticed before, such as this image of the back of a man’s head. For quite a long time now I have photographed fragments from television and film, as a way of trying to find something original in a copy. There is little that is original anymore because everything is referenced, as this image is, but I think you can show something accidental in the hope of it acquiring resonance.

What was it about The Man Who Fell To Earth, and the very public figure of David Bowie, that appealed to you?

It was a film I happened to watch again—The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976)—and had quite forgotten how much it influenced a film I made a few years later called Radio On (1979), not in any obvious way, only in my head. There are many cross-references I had forgotten about. Both films, although very different, are about technology and future. The growing bank of monitors and screens that feature in The Man Who Fell to Earth I quoted in Radio On. The Man Who Fell to Earth was prophetic for anticipating how our primary relationship would be with the screen.

You’ve chosen an image of the back of Bowie’s head, which questions the necessity to show anything when everything is seen to such an extent already. Was your choice of this particular shot purposefully random, or do you feel it captures something very specific for you?

No, randomly purposeful! It was just a moment I noticed within the larger frame that I thought was worth capturing.

Is it fair to say there’s a sense of loss for you in this project? Loss of the image’s power; loss of poignancy; loss, even, of Bowie?

No sense of loss, really. We live in an age of post-cinema but that’s progress. Everything changes faster now. There’s no point in mourning the past. In a way, the image has become more powerful now. It is on the rampage. I was surprised by the reaction to Bowie’s death. I am sure he would tell you if he could that he was just an entertainer.

You work in the world of images, but also words. Do you feel there is an equivalently large shift within writing as this change and over saturation that has happened to images in recent years?

Writing remains a peasant activity. Tillage. Moving words from one part of the field to another, and then back again. It is a solitary activity but not lonely. The image bank, which is a product of the Internet, shows that everything is both lonely and not lonely. We now live in a world of screens, actual and psychological. I suppose what I am searching for is moments of pause in the rush forward that might make you stop and think for a bit before moving on.

‘In What’s Missing, Is Where Love Has Gone’ shows until 20 May at Decad, Berlin. decad.org. Photography by Roman März