We are living in the age of digital distraction. We are told to pay attention to our digital health, and to set sensible limits to our online consumption. Apple introduced a weekly Screen Time report function last year, supposedly to enable us to “make more informed decisions”. But just how much of a choice do we really have? What distinction can we draw between our online and offline lives, when (particularly for the creative industries) career advancement can hinge on how “online” we are. And who is to say which version of ourselves holds greater value?

Cory Arcangel is familiar with the highs and lows of the internet. One of the first artists to be widely recognized for embracing video games, websites and software, Arcangel became known for works such as Super Mario Clouds (2002), in which everything is removed from the game except for its drifting clouds. He uses digital media to explore its rapidly expanding role in our daily lives.

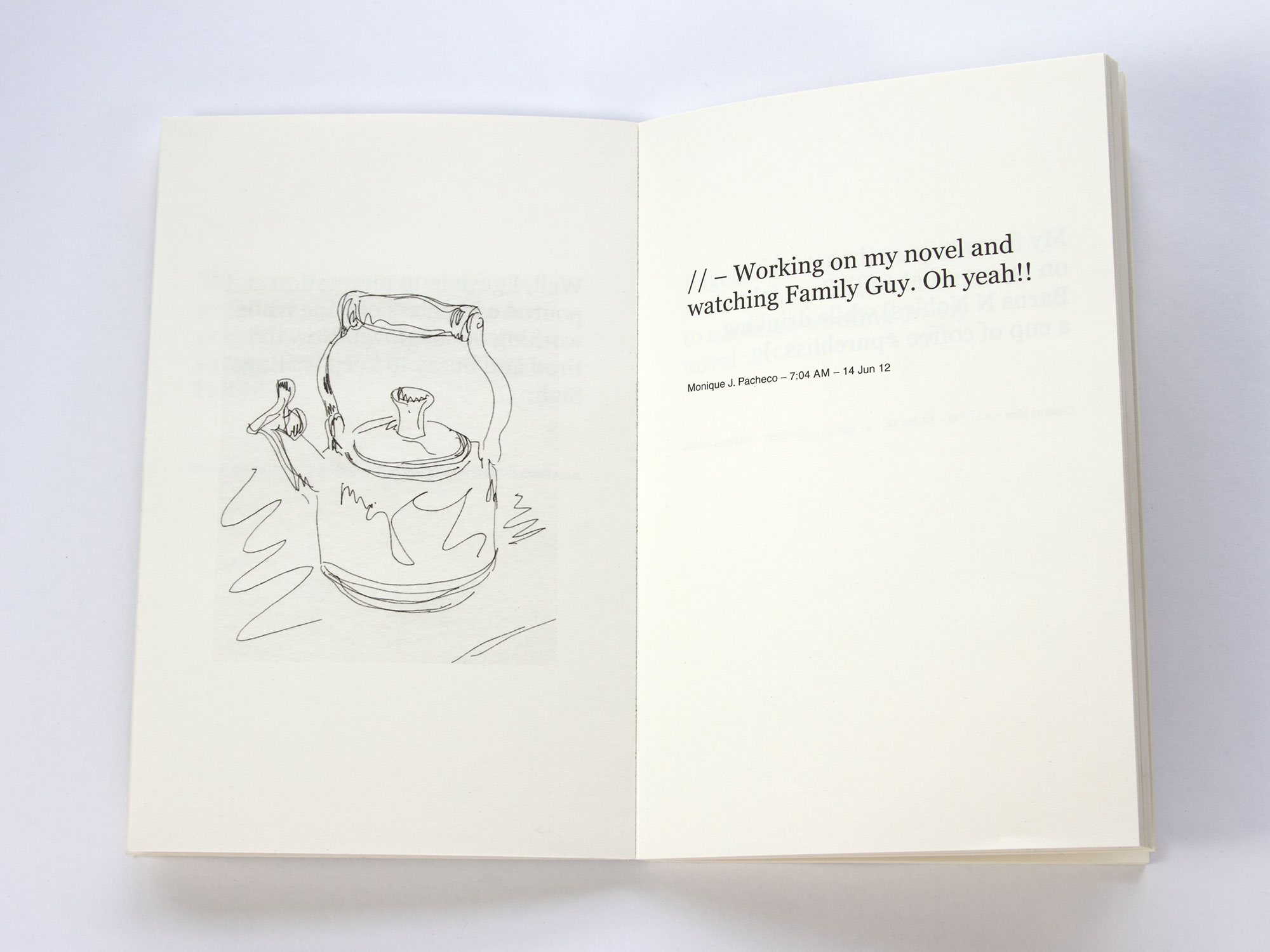

In Working On My Novel (2014), a compilation of tweets that include the phrase “working on my novel”, Arcangel continues his interest in appropriation. The project began its life as a Twitter feed consisting of retweets, but took on a different tone when Penguin published highlights from the feed as a physical book—a novel of sorts.

“What distinction can we draw between our online and offline lives, when career advancement can hinge on how ‘online’ we are”

“What does it feel like to try and create something new? How is it possible to find a space for the demands of writing a novel in a world of instant communication?” he asks in his introduction to the book. The question of newness is never far out of sight in Arcangel’s work; he raises age-old questions of authorship through the recycling of popular culture, either as it happens or just after the fact.

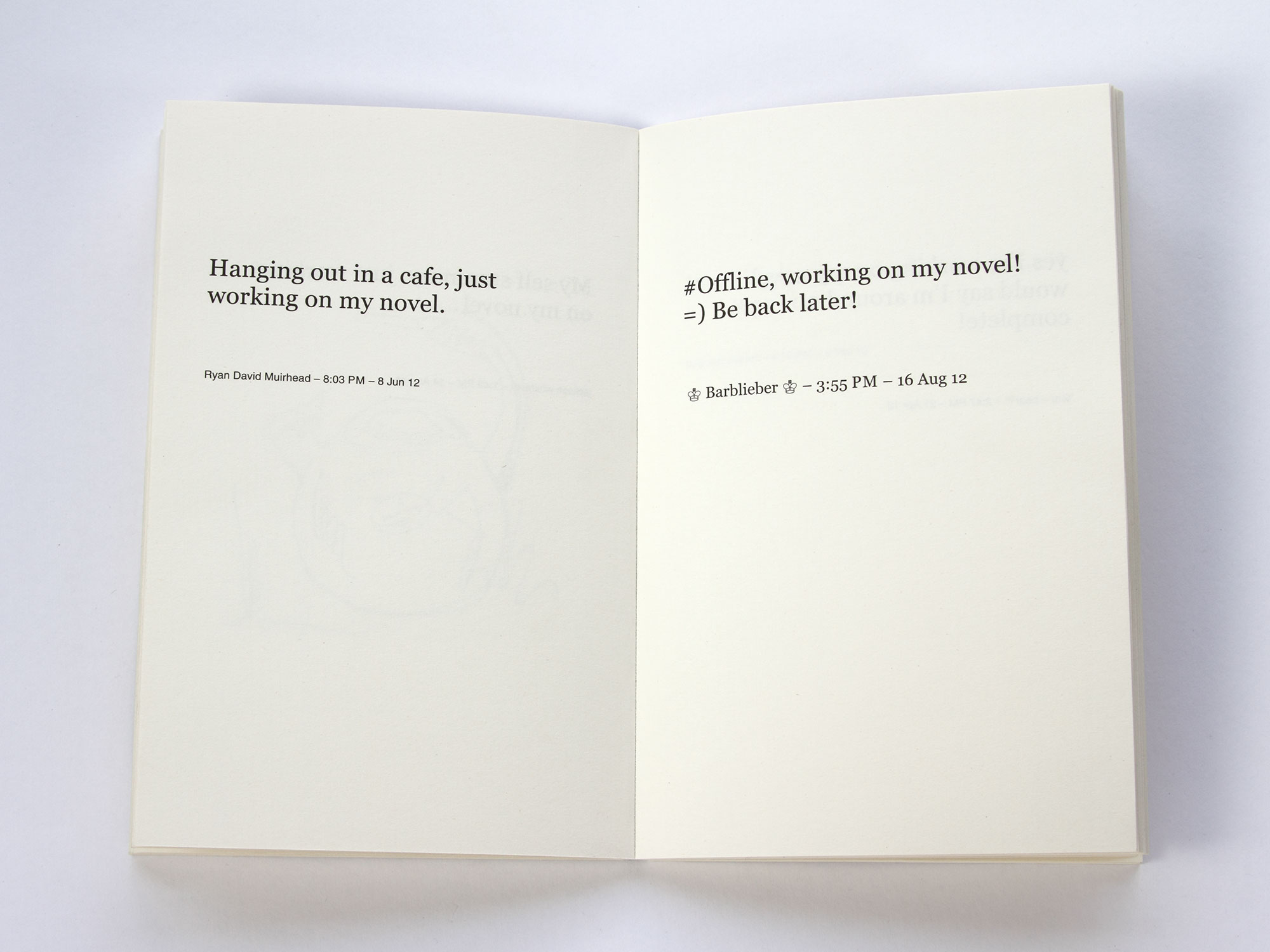

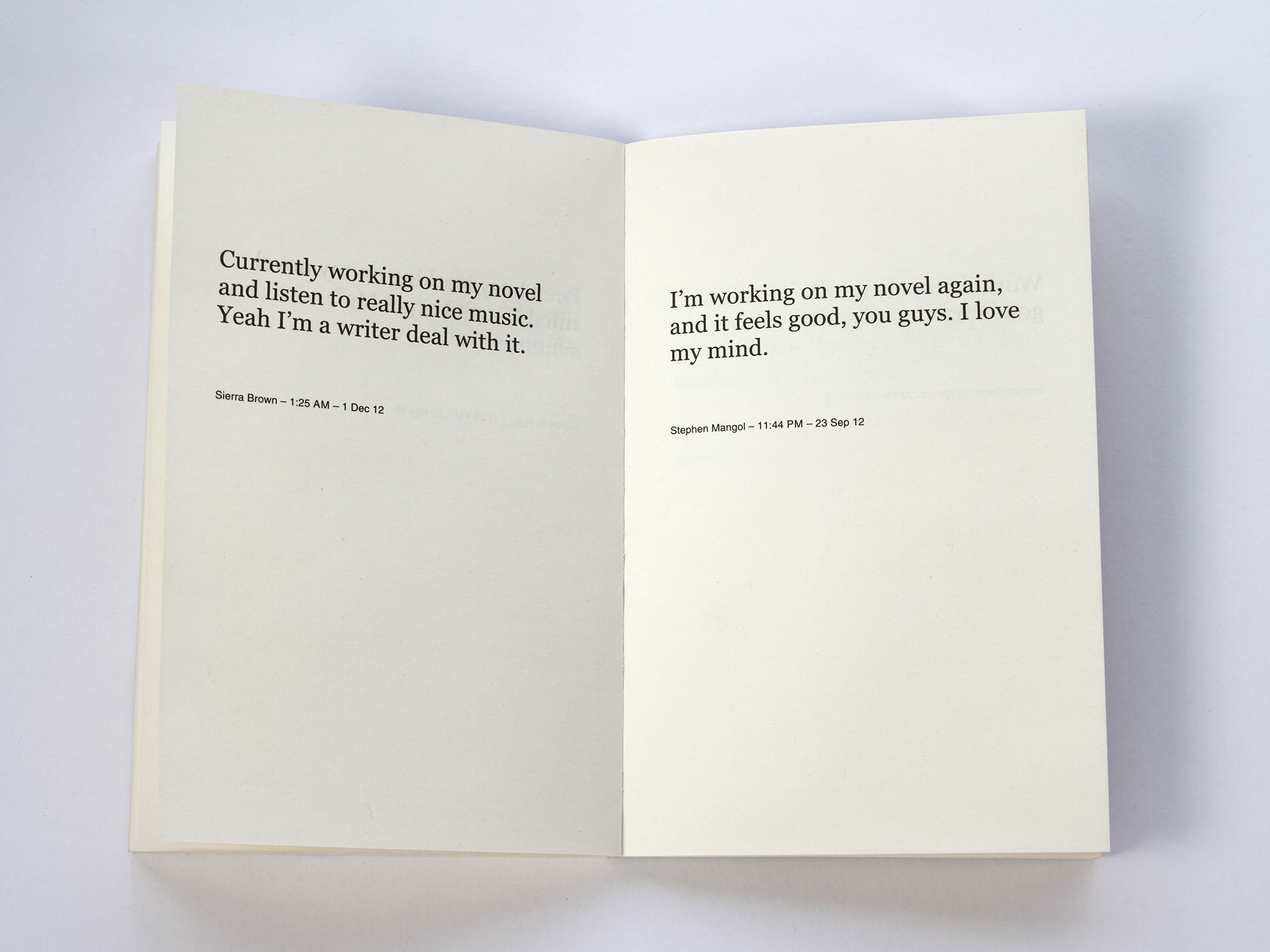

Working On My Novel highlights the blurred line between our real and our virtual selves. One tweet reads: “Hanging out in a cafe, just working on my novel.” Another: “#Offline, working on my novel!” The offline world is present even when it becomes nothing more than a hashtag, and the physicality and locality of the author’s personal surroundings paint a picture of life lived in liminal space.

In Sleeveless, Natasha Stagg’s recent book of essays on fashion, image and media, she writes, “We say that the internet and literature are separate, except that one can be found on the other. To ignore certain impulses that dictate our lives, and to write in earnest about living: Is this disingenuous? Is your relationship with the internet masochistic? Do you feel like it drains you of money, time and dignity? Me too, and when I am trying to write, it taunts me, existing in the same space as the one in which I write, and choking my thoughts like a hangover.”

The masochism that Stagg describes underpins Working On My Novel, like a hunger that cannot be sated. The aspiring writers snapshotted in Arcangel’s book are seeking gratification. They want to feel full, or to feel fulfilled, and Twitter offers the rapid feedback that the lonely conditions of novel-writing preclude.

Ambition and failure go hand-in-hand: it is impossible to fail if you never tried in the first place. In Arcangel’s work, the question of dignity is a difficult one. Working On My Novel is undoubtedly humorous, an easy read and an easy laugh, but, then again, irony has always been easier to pull off than sincerity.

The people quoted in the book might have been surprised to find that their first publication was not in the context of their novel-in-progress, but in Arcangel’s adaptation of their Twitter presence. Somewhat reassuringly, all of the tweets collected in the book are used with the permission of the original authors.

“It deals with time in a different way and it’s in a different space, but there is hopefully real truth and something honest about what it means to be human in all of it,” Arcangel said in an interview for Elephant in 2015. “I wouldn’t have spent three years on Working On My Novel if I thought it was just something funny. There has to be something true in it.”

“Twitter offers the rapid feedback that the lonely conditions of novel-writing preclude“

It is a dilemma that feels more relevant now, in 2019, than when it was first released in 2014. When Arcangel devised the project, the term “influencer” was still nascent. Five years on, and the story of Instagram influencer Caroline Calloway and her now-shelved novel looms large. She is the perfect poster child for Working On My Novel.

In a viral essay by Natalie Beach, her former friend and ghost-writer, Calloway’s doomed aspirations to fulfil a book deal—offered to her on the basis of her influencer status (she has amassed 780,000 followers since joining Instagram in 2013)—are laid out in painful detail. That the book never came into being, due to a combination of mental health issues, narcissism and digital distraction, feels like a tale fit for our times.

Working On My Novel makes visible the traces of books that might never be, like waves leaving a line of litter on the beach. It is the digital detritus of unrealized dreams.