Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition, Baltimore-based artist Cynthia Daignault, who uses painting to explore monument and memory, reflects on the profound influence Felix Gonzalez-Torres has had on her career.

A lot of work affects you in little ways, but certain things affect you in seismic ways, really shifting and shattering your whole practice. I’m an art historian by training, and after graduating from school I spent a few years working for the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation during my twenties.

Getting very deep into the work of an artist is almost like an apprenticeship. My experience at the Foundation had a really seminal effect on my painting practice, and also on how I think about art in general, and what I want out of my own art.

I think Felix is an artist’s artist. He’s held in this almost saintly position, due to both the work and his biography. It was a real honour taking care of his legacy, celebrating and exploring the ideas. There was never a day that I didn’t feel really moved by the work.

“How much can you remove from a work without at all decreasing its meaning or magnitude?”

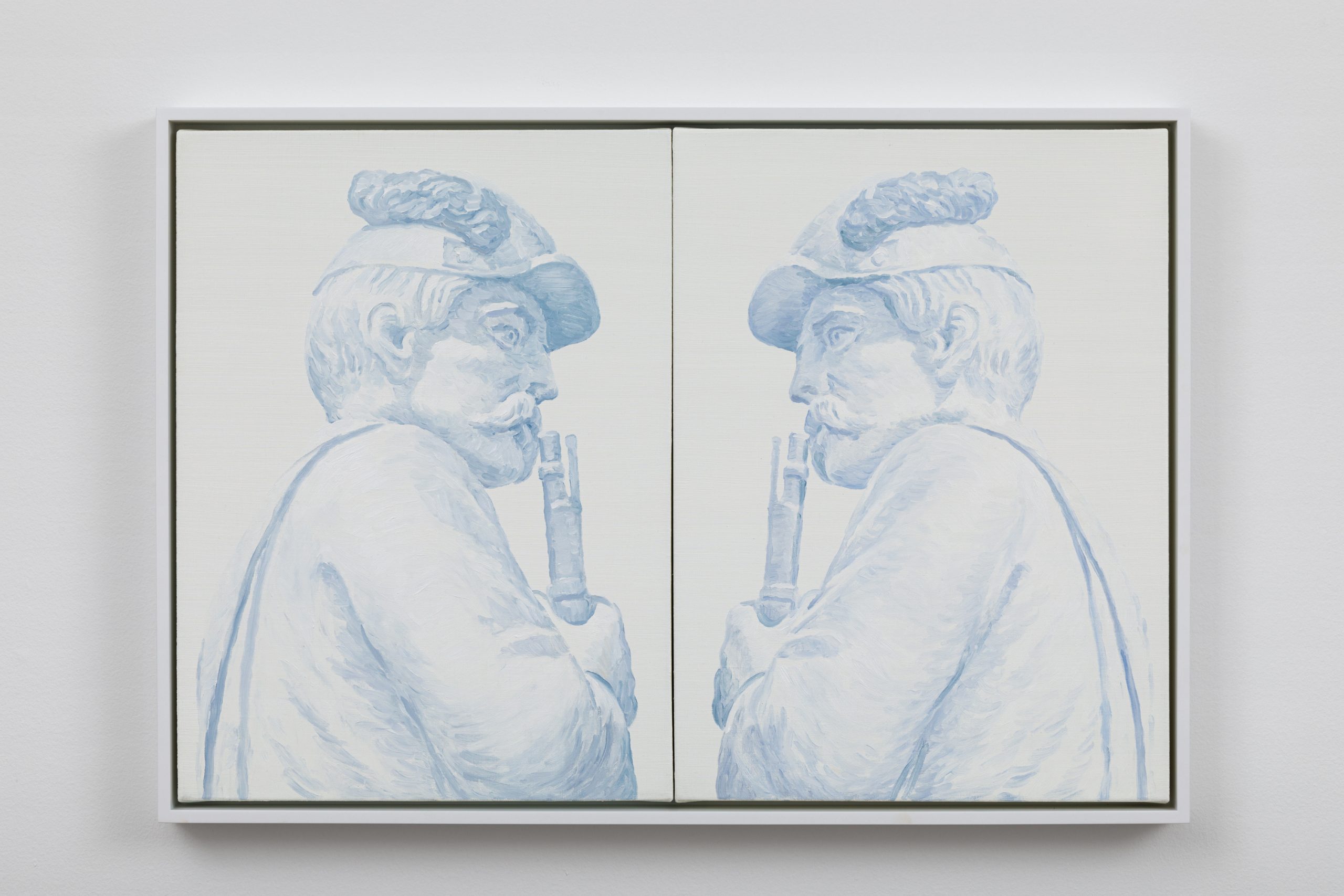

His work was revolutionary, in terms of how people think about sculpture and the bounds of it. Obviously, his works are concepts. There’s a set of instructions or boundaries communicated to an exhibitor or a collector in a certificate of authenticity, and the physical manifestations are iterations of this idea.

Could a painting be site-specific, or change in different installations? Could you stand inside of it? I was moved to apply in my own work as a painter some of the ideas that he had explored through sculpture. In “Untitled” (Placebo) (1991), the candy pieces can be a carpet, a strip, a pile, a scatter. The flavour, the shape of the candy, lots of things shift.

The work can be and has been all these things. Whether the candies are replenished every day or diminish really shifts the experience of it. It can be metaphoric to an ailing body, or a galaxy of stars, or a disco of lights; the piece can lean in very different directions.

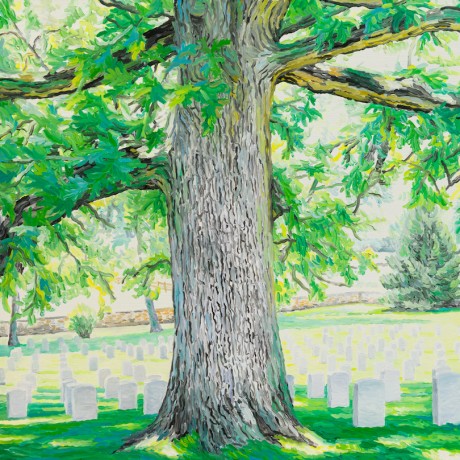

I loved the idea that a painting could breathe like that. That was the word I started to use: could you make a painting that breathes to fill a room, or contracts the way that lungs do? When I started working on my new multi-panel works, it was a response to this idea. My piece Light Atlas has been installed as a room, as a panorama on a large wall, and as a cyclorama (a single line of paintings that connect around a circle).

I wanted to consider how a work could relate and bend to architecture. I thought of a painting which doesn’t just present to you as a stalwart and intractable rectangle. It could be mutable or malleable and still be a painting, and that came directly out of “Untitled” (Placebo).

I work every day in a painting practice that’s very solitary. It’s conceptual and it’s emotional, a place that you can communicate both ideas and feelings in visual media. I took that from Felix’s work, this idea of both emotion and of minimalism.

“We talk so much about what a painting is about, but could you just feel a work?”

After I saw “Untitled” (Placebo), my own work really changed with this idea of emptiness and fullness. How much can you remove from a work without at all decreasing its meaning or magnitude? How much could you strip away and everything is still there?

Felix’s works are so full; they’re about everything. They’re about the entire AIDS crisis, and love and death and the cosmos, and yet it’s just a pile of candy. There’s nothing in it. So empty, yet it contains everything. They’re very emotional works. Could painting operate that way for me?

We talk so much about what a painting is about, but could you just feel a work? Could it be so non-language based that it’s about body and not mind, just this essential nugget of feeling. I am striving to go to that place where it can become so full and yet so empty.

“Could you make a painting that breathes to fill a room, or contracts the way that lungs do?”

With artists who are really seminal to us, you return to them over time, and at different phases of your life or your art production. Amidst different cultural moments, you will see different things in their work. After the 2016 election in the US, it was the political side of Felix’s work that resonated with me.

Now we’re in this moment of the pandemic, and his works about medicine and the body connect to that. This is a wonderful piece for this moment because all of its metaphors are specifically about wasting, about placebo, about medicine, about the pharmaceutical industry and the failures of the government in regards to public health

Felix is a model for me of how you can be a political artist without being didactic. All of his works are political, frankly. They’re about the AIDS crisis, and the failure of the government, and the failure of Big Pharma. These works are so powerful, and so non-didactic, and so timeless.

As told to Louise Benson, Elephant’s deputy editor