Seven years ago as I sat in the chapel of Christ’s College, Cambridge, I encountered Tom de Freston’s two painted panels titled Deposition, which stood side by side at the altar and seemed to absorb all of the afternoon sunlight, consequentially plunging their audience into a warm, cocooning darkness. Two figures, one falling and one rising, were suspended mid-air, as guests of the exhibition sat lined on either side, meditating on a representation of resurrection that could be religious or secular, or a contemplative fusion of both.

Seven years ago as I sat in the chapel of Christ’s College, Cambridge, I encountered Tom de Freston’s two painted panels titled Deposition, which stood side by side at the altar and seemed to absorb all of the afternoon sunlight, consequentially plunging their audience into a warm, cocooning darkness. Two figures, one falling and one rising, were suspended mid-air, as guests of the exhibition sat lined on either side, meditating on a representation of resurrection that could be religious or secular, or a contemplative fusion of both.

Questions of devotion, transcendence—and their deviations—have persisted in De Freston’s work over the years. In the past two years alone he has published a graphic-poetic exploration of Orpheus and Eurydice with his wife, the poet and novelist Kiran Millwood Hargrave, as part of a wider project involving film, painting and music; he has put together exhibitions for the Wellcome Institute-sponsored Medicine Unboxed project; painted a triptych for The Bodleian Library inspired by King Lear and created an Artists’ Bedroom Commission for Battersea Arts Centre.

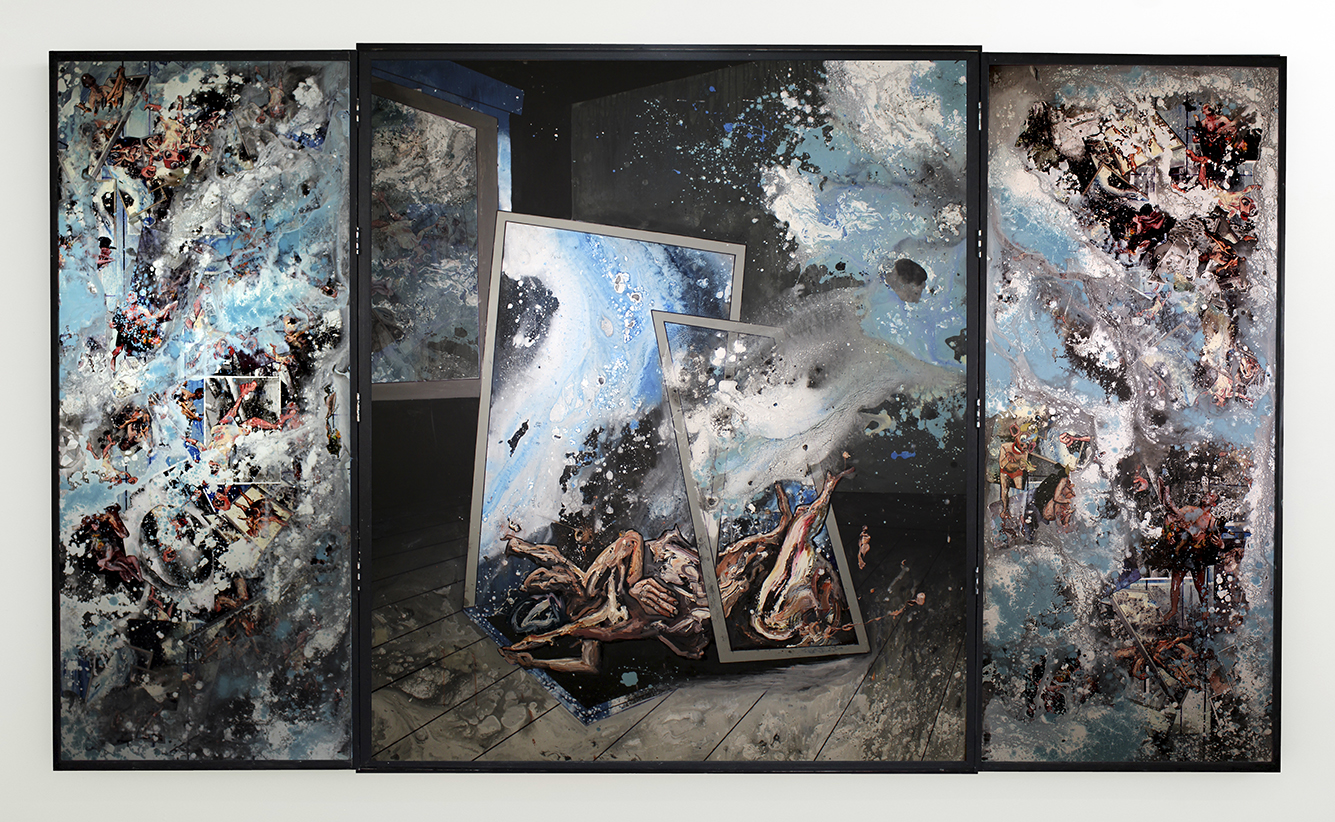

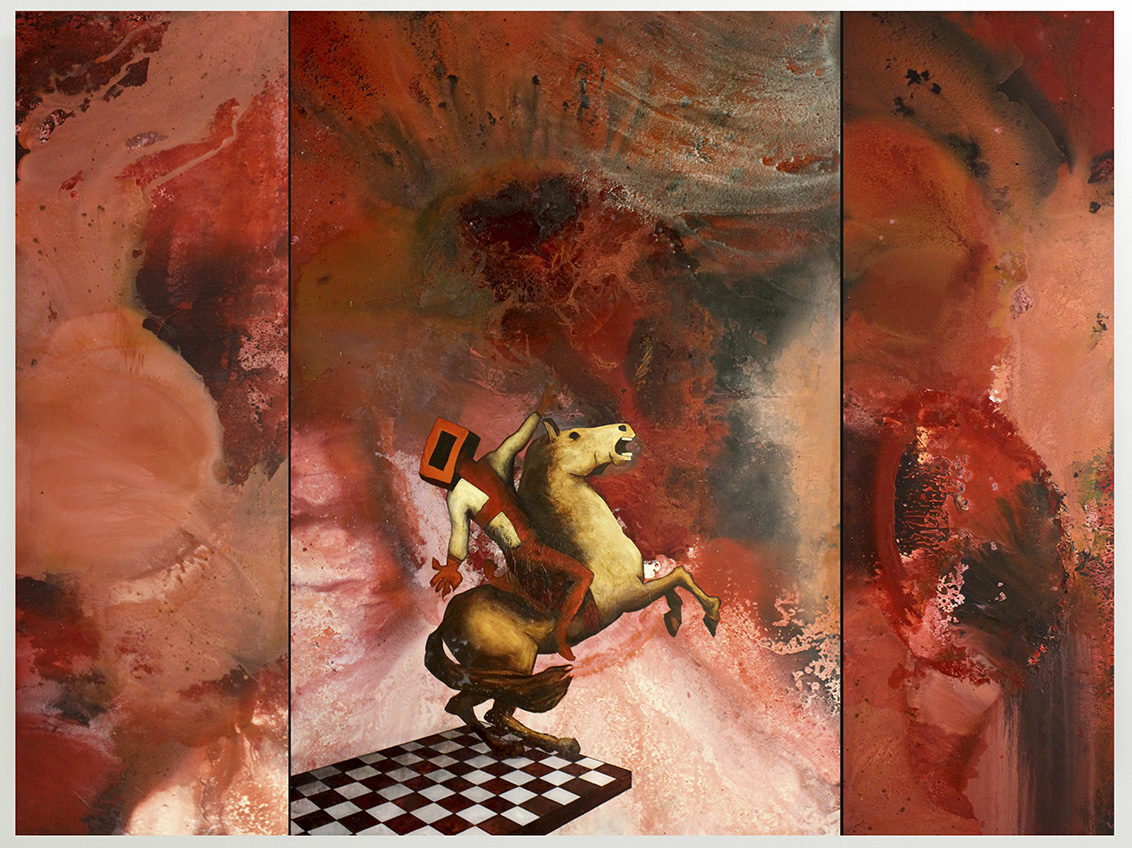

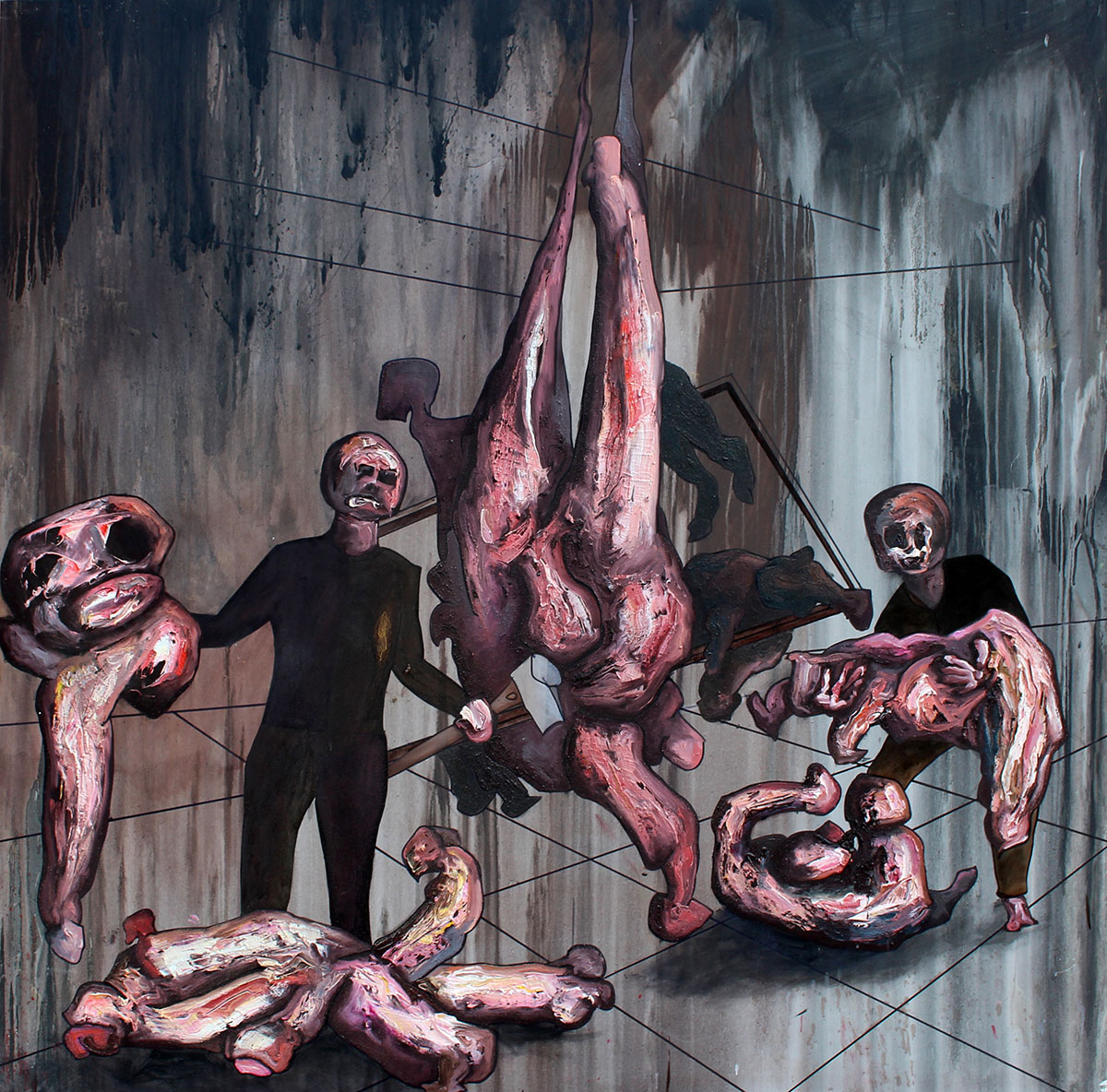

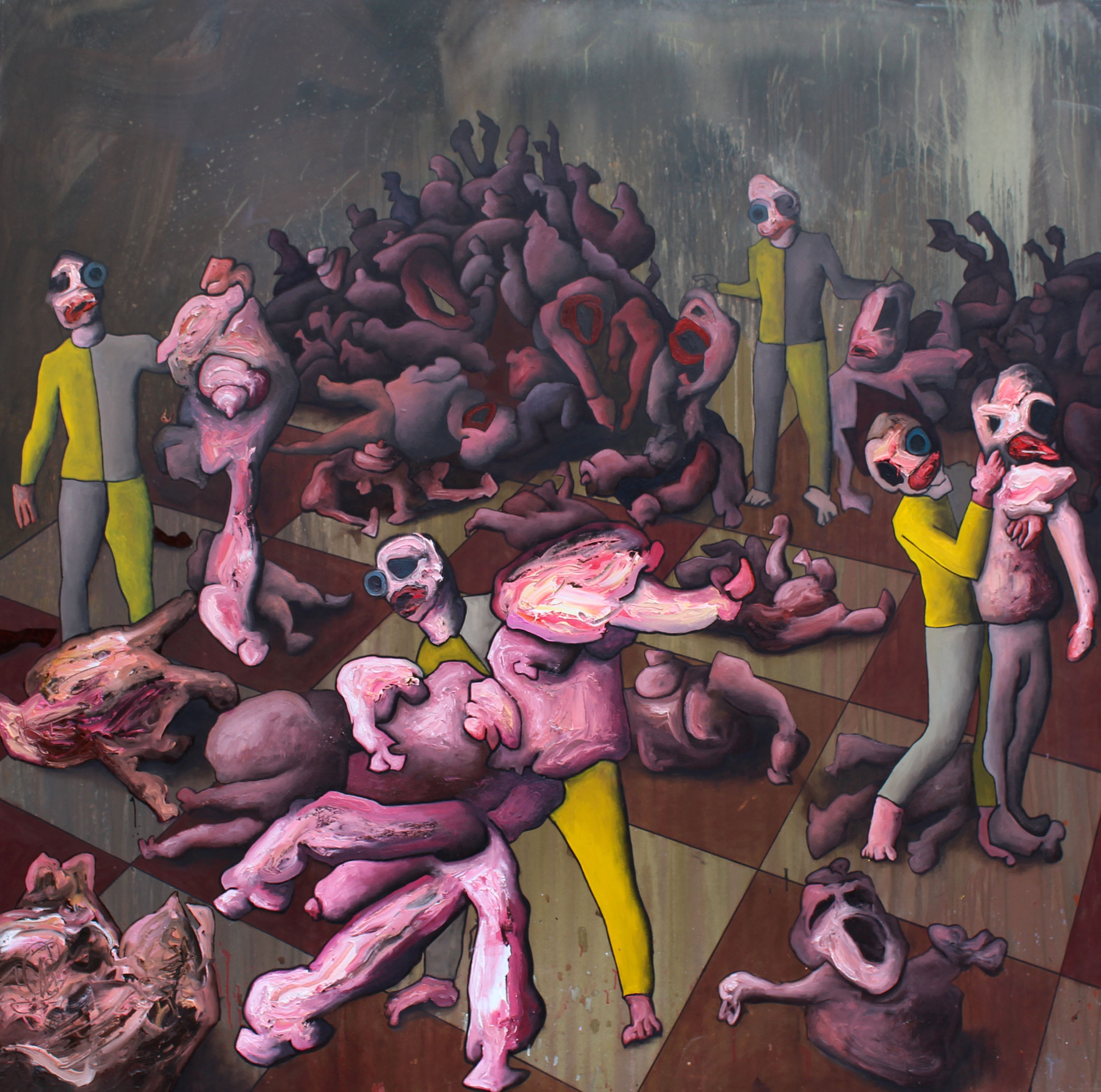

An immersive connection with the audience is a compelling characteristic of De Freston’s work, and Demons Land, a multimedia collaboration with Simon Palfrey (academic and writer) and Mark Jones (filmmaker), is the latest manifestation. Working with Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene and imagining a “poem come to life”, Demons Land creates a dystopian, hellish world through which viewers can reflect on the nightmarish depths of the human soul, and why people act as they do—not only in hallucinatory figments of the imagination, but in the real-world phenomena of genocide, fascism and abuse. I spoke with the artist.

In Demons Land you produced thirty large canvases and two 9×9 grids of smaller paintings, as well as co-directing the film. How did you work together with Mark and Simon? Did you keep one another in the loop throughout the process, or was it more independent in practice?

It was closer to a process of discovery than planning. It started with Simon’s script, which was originally a play text, a reimagining of Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queene. We then set about working as a three, and with a wider cast of creatives, exploring how we might bring that text to life—translate it into a new form. One of the results is a multimedia exhibition, which brings paintings, film, sculpture and text together to tell the story.

Then of course there is Spenser’s poem itself—both the source of Demons Land and also the foundational text of the whole project—in its themes, its structures, its endlessly repeating rhythms and rhymes, its characters and life-forms. There was no desire to illustrate either text, we wanted to take the philosophical and formal underpinnings of Spenser’s truly unique vision and remain true to that. A central question set up at the start of the project was what would it mean, in all its beautiful horrifying actuality, if a poem was to actually come to life?

One of the key approaches we wanted was for a genuinely porous relationship between different types of thinking and different disciplines, so that there was no top-down hierarchy between the makers of the mediums. In practice this meant that for four years we have worked remarkably closely together, culminating in the joint direction of the film. What we wanted was a genuine collaboration, where critical thinking and creative thinking were not separate but one and the same, bleeding into and out of each other. As such I see the grids of paintings and the large canvases as made by me but as the product of genuine combined thinking.

Your use of poetry, and indeed your collaboration with poets over the years, has been integral to your own development. Where is this concern for narrative rooted? When did you start seeing painting as a form of storytelling?

I spent four years during a foundation and my fine art degree making purely abstract paintings. I finished that degree feeling frustrated and a bit lost and that’s when I decided to go to Cambridge to study history of art. Really early on I realized that what really interested me, and what always had, was painting images and thinking about how painting could be used to deal with narrative. I think we are instinctively image-makers and storytellers, and there’s something about painting’s connection to the deepest roots of this history that interests me.

Demons Land engages with very difficult themes, including cultural genocide and fundamentalism, temptation, persuasion and even redemption; how did the process of painting and filmmaking expand your own understanding of these issues?

In the process of reading extensively around the histories and themes at the centre of the project, my main concern was whether it was our story to tell, whether there was a danger of perpetuating, exploiting or appropriating the histories. This was particularly true around issues of gender, sexual violence, colonial genocide and historical trauma. Our world might have been fictional, but it was built totally on real histories and experiences, it meant there was a weight and responsibility. For me the only way into this was to not ignore those issues but to admit you were seeing them from a particular perspective, that you had to face up to the manner in which you might be complicit in these histories.

“Paintings are a kind of wound, so its no surprise the subject matter I am drawn to is often similarly focused on trauma and violence”

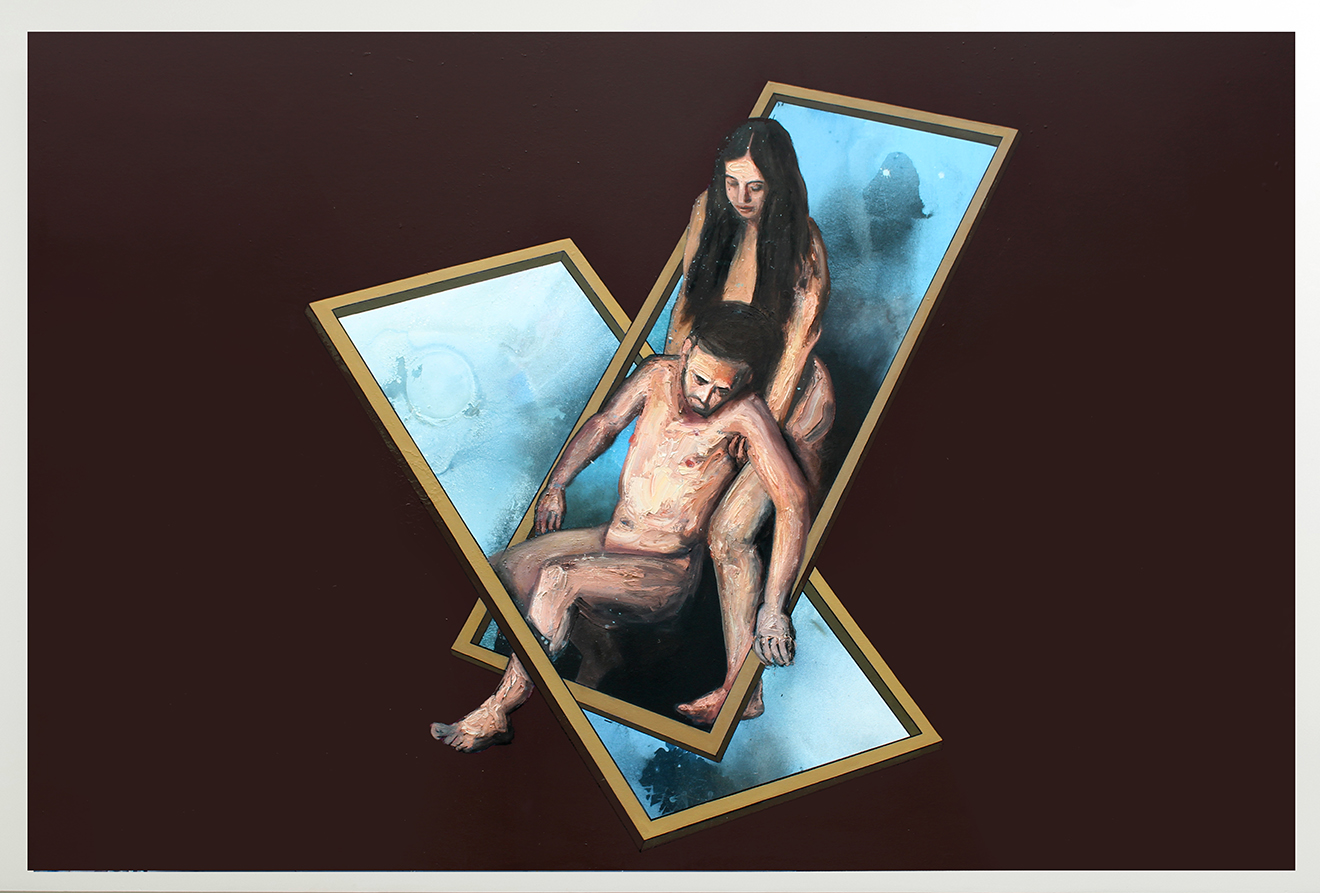

In your earlier work, the experience of trauma—whether in a personal, religious or societal sense—is weaved into stories and imagery. Can you tell me a little more about the relationship between trauma and painting, for you?

I’m drawn to moments of rupture, fragments of stories that contain multitudes—that seem to carry the weight of entire histories within one instance. Paintings offer a chance to express these vertiginous gaps in the horizontal flow of a narrative. It means paintings are a kind of wound, so its no surprise the subject matter I am drawn to is often similarly focused on trauma and violence; historical, political, personal and physical. Recently the shift has been towards paintings which try to express complex personal psychologies, as authentically as possible.

Is the process of painting itself therefore a healing one for you, then?

I don’t think I ever saw painting as healing; that seemed a romantic and fanciful idea, giving art too instrumental a role. I was also in total denial about my work having any direct autobiographical content. It’s become obvious this was a form of denial though, and in all kinds of ways painting has saved my life. Now I’m very aware that if I don’t paint, my mental health suffers. Once you strip away the intellectualizing, it’s clear there’s something far deeper and more fundamental about the creative drive.

James Cahill meets Tom de Freston in Elephant issue 12

BUY ISSUE 12