Rotten food has long been used by artists for all its suggestive potential. Historically, mould was depicted in still life paintings as a symbol of human death and decay. There is something gruesomely appealing about a perfectly painted plateful of rotten fruit, coated in a delicate layer of green fluff, oozing smelly-looking liquid substances, perhaps garnished with the odd maggot. The attention to detail required to capture the foulness of mouldy food in paint has something quite exquisite, albeit appetite-killing, about it. Artists in recent years have also turned to rotting food in their work, often presenting it via the camera lens, and the theme has been blown wide open.

- Klaus Pichler, Barbecue Sausgae, 2012 (left), Cauliflower, 2012 (right)

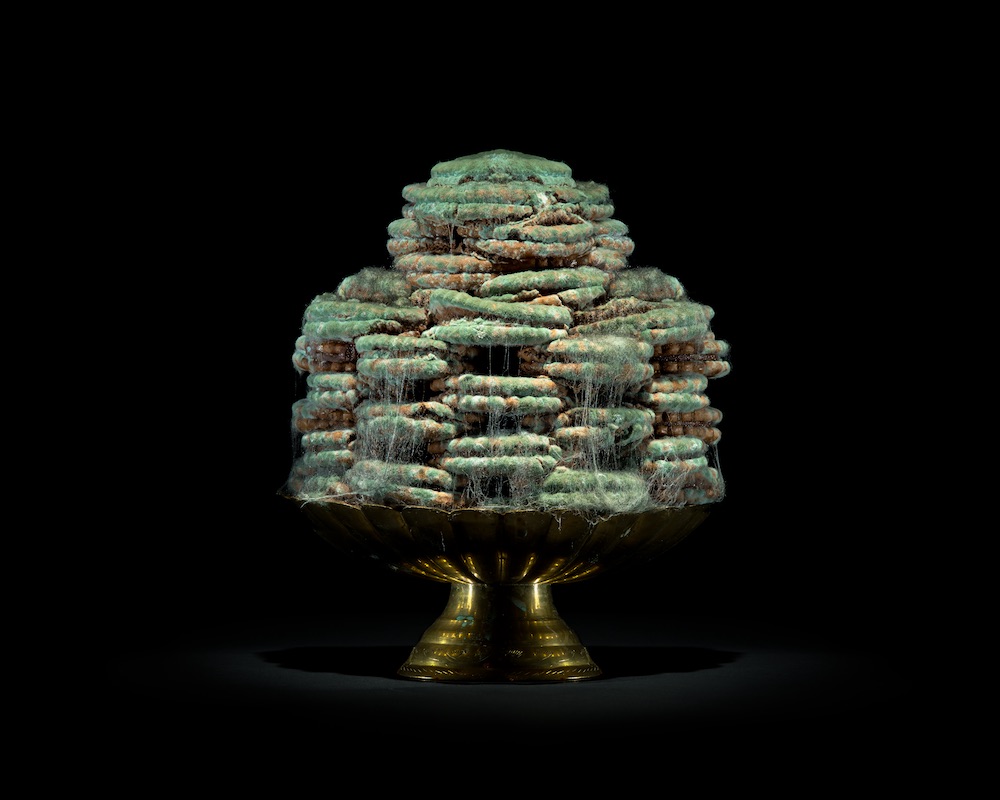

Within the context of an ever-more-urgent climate emergency, the question of waste and unnecessary food production is an important one for artists. “I knew from the beginning that I wanted to put wasted food into focus, particularly in household amounts, in order to both depict the luxury of the daily availability of food and also to describe the means of global food production,” says Klaus Pichler, an Austrian artist whose haunting images of mouldy food shot against a black background were triggered by the monumental quantity of global food waste. Pichler’s One Third project places environmental and ethical concerns front and centre; the works have an accompanying text which explains UN findings that one third of all food produced goes to waste—mostly from industrialized nations in the global north.

“In order to depict that in a dramatic way,” he continues, “I was inspired by the classic vanitas, still life paintings from the seventeenth century, Dutch master paintings and the aesthetics of luxury advertising photography. My goal was to create images which were both beautiful and disgusting at the same time, to depict the luxury and beauty of food and also the fact that food is being wasted in a large extent.”

“My goal was to create images which were both beautiful and disgusting at the same time”

While the images themselves can be accessed and understood on a pretty immediate level, it was important for Pichler to carry out meaningful research into his topic. “I have been cooperating with a local food and environmental NGO called Global2000, which was able to provide accurate data,” he tells me. “There have been plenty of surprises—for instance that it is cheaper to import garlic from China or onions from New Zealand than producing them in a local way, or that one kilogram of beef requires 5800 litres of water. In my humble opinion, the current food waste would easily be reducible if everyone followed a few easy rules (buy locally, just buy what you can eat) and if supermarket policies towards ‘imperfect’ food, the permanent refilling of the shelves and overcautious practices towards ‘best before’ dates would change.”

Food Chain Project, created by Itamar Gilboa, also looks at consumption, representing one year’s worth of food and drink digested by the artist in the form of clean, white sculptures. In this case, the artist actively avoided the inclusion of rotting goods to make his point. “I didn’t want to use real food because it’s a waste,” Gilboa tells me. “I also decided to take all the branding away, which is why it’s all white sculptures, so they concentrate only on the food and not the marketing and advertising behind this industry.”

The works are often displayed in a supermarket-style set-up, where the individual items are on sale to visitors. “I wanted to inspire people to think about their own consumption and also get involved if they want, so I joined with a few NGOs. One was the New Food Movement, which is related to the Slow Food Movement in the Netherlands. They teach children about the environment but also how to approach food, how to make food, what is good and bad for them. And also Fairfood International—they are more involved with corporations and governments to make new legislations to make this world a better place.”

But how do people respond to these works? “There are always remarks about the bad things I consume: ‘Oh, you eat so much chocolate’ or ‘You drink so much Coca Cola Light’. But after that they really start to think about their own consumption. When kids come from schools come to see the exhibition, they also get an assignment to make a diary for a day or a week and decide what is healthy or what is not.”

The cleanliness of the items and the absence of mould and rot here points to the fact these items were in fact consumed, rather than left to waste away. They appear as the ultimate, clean still life, and connect with the perfectly formed goods we find in supermarkets, before the decay sets in.

“I didn’t want to use real food because it’s a waste”

Sam Taylor-Wood’s Still Life is the exact opposite of clean. In the 2001 video work, she plays with the traditional still-life format but imbues it with a contemporary aspect of time, as a bowl of fruit slowly slumps and collapses. It eventually becomes overrun with mould, from the cute and fuzzy variety to the dark and sticky, hellish variety. Flies buzz around towards the “end” of the looping film; the dignity of the vanitas paintings becomes something far more horrendous. The message here isn’t so much that we are going to die, but that when we do, it is likely to be long, arduous and pained.

While the very sight of mould, even in image form, can be enough to send shivers down the spine (I had my fists grasped for the entirety of Taylor-Wood’s film, in anticipation of the inevitable onslaught of flies and maggots) it is—on occasion—also used to play humorously with the viewer’s sense of disgust. Sometimes it’s presented as an altogether rather attractive material. In the case of Maisie Cousins, whose gooey, brilliant work we showed at Elephant West last year, mouldy foodstuffs are combined with more appealing, vibrant edible forms. Mould, maggots and flies hang out with items we might actually like to eat, creating images that are simultaneously mouth-watering and contaminated. “I’m interested in being human and all the delicious and gross things that come along with it,” Cousins has previously said of these playful works.

Cindy Sherman has also used mould as a way to test her viewers’ reactions—in the 1980s she photographed scenes covered in fake vomit and rotten food for her Disasters series. She has since said this was a response to her status as the art world’s darling; she wanted to see how far she could push things. “I was like, do they really like the work? Well, let’s see them put this over the dining table—I had fun making those pictures.”

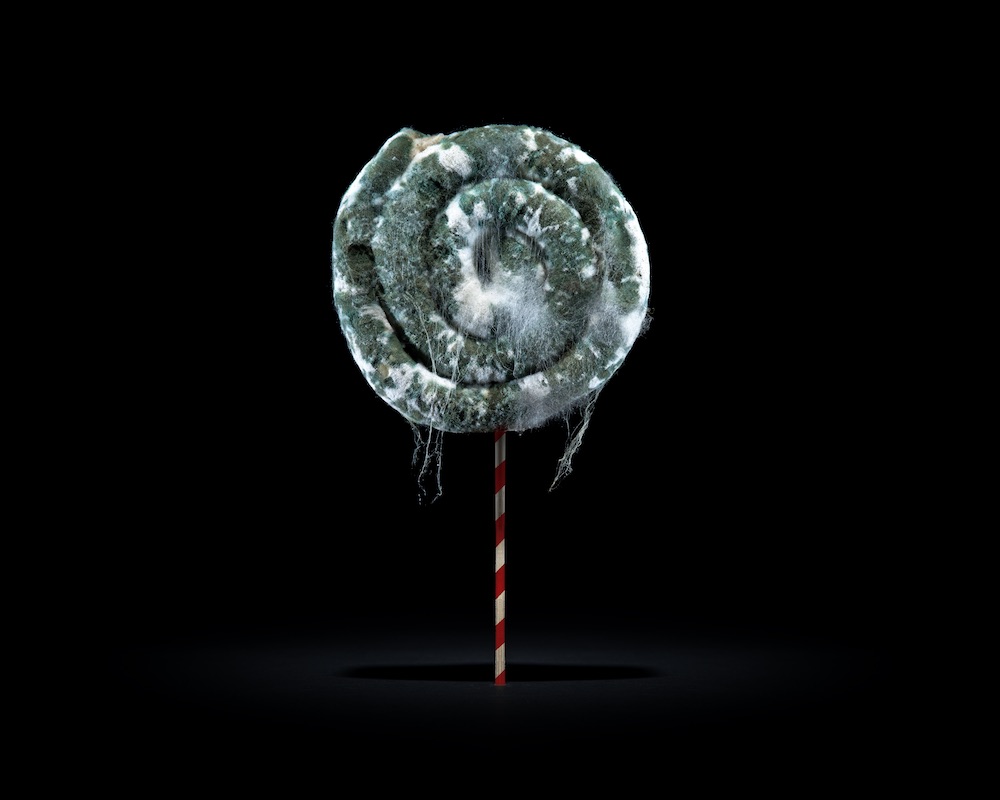

- Kathleen Ryan, Emerald City, 2019 (left); Sour Spot, 2019 (right)

Some artists completely subvert the natural disgust that we have towards mould: for her works Semi-Precious Bone, Fool’s Mould and Sour Pearls, Kathleen Ryan created lemon sculptures covered in beads; yellow glass for the healthy bits of the fruit, and luxurious materials for the mould that clings to it. “For all three works, the value is in the mould,” she tells Alice Bucknell in the current issue of Elephant magazine. “The yellow parts are just glass beads, but the bits that have ‘gone off’ are made from luxurious yet natural materials—crystals and semi-precious and precious gemstones; there are also freshwater pearls and carved bone and coral beads.”

“Fruit is dying, but mould is thriving, by using natural materials for the mould it has this energy to it that you can feel”

The mould in this case is beautiful and delicately formed. “All the works have something to do with mortality—like in vanitas paintings; ivy vines, shells, fruit, depicting decay and death and rot—but they are very much alive. Fruit is dying, but mould is thriving, by using natural materials for the mould it has this energy to it that you can feel. They lemons are dying but they’re also suspended in this buzzing aliveness.”

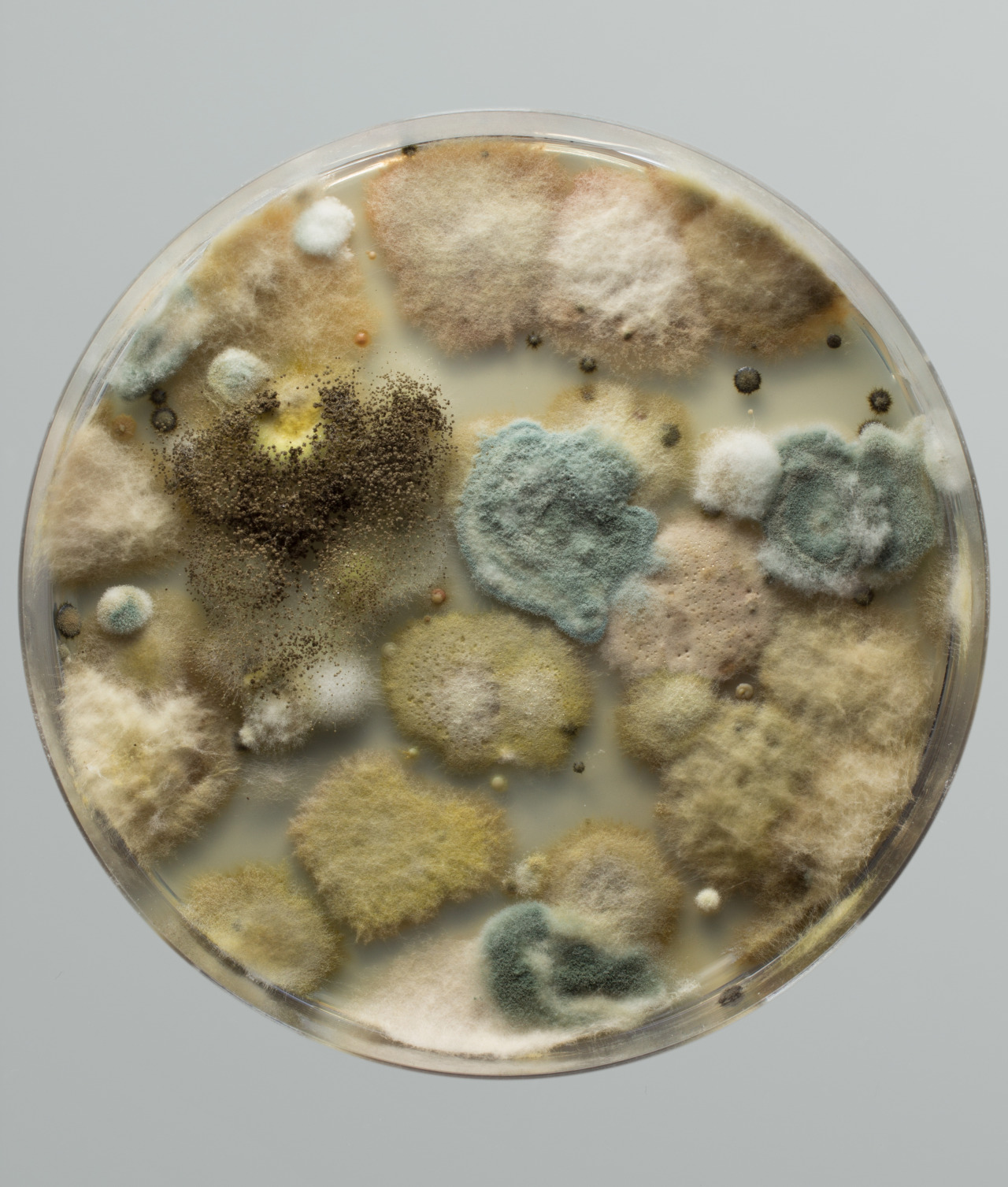

- Antoine Bridier-Nahmias, Magical Contamination, 2013

Antoine Bridier-Nahmias doesn’t even translate his mould into a different material to highlight the beauty that lies within it—on his Tumblr page Magical Contamination, he simply presents photographic images of Petri dishes containing different mouldy substances. In these images, glorious patterns are revealed, showing the ordered structure that makes up these different forms. “I use different lab media in my plates but all the micro-organisms that grow on them are perfectly random contaminations,” he answers one visitor on his page, “I don’t ‘do’ anything per se

to achieve particular patterns.”

As to the science of it all, Bridier-Nahmias is more interested in the look of it. “I can tell you in that in general those are molds (fungus), bacterias and yeasts,” he tells another visitor. “In order to know which organism is living on each plate one could perform some test (from the simple API gallery to the genome deep-sequencing) but my interest for now is only visual.” The visitor feedback throughout Bridier-Nahmias’s page is resoundingly positive, full of phrases such as “utterly divine”, “absolutely stunning” and “beautiful bastards”.

Perhaps, once mould is separated from an item we may ordinarily like to eat, we can appreciate the truly artistic nature of its tiny individual forms.