Art has long been used as a means not just for personal expression, but as an agent of change and persuasion—be that around politics, love, gender perceptions and now, with more urgency than ever, the climate crisis. Numerous artists are making work that bemoans what people have done to the world. They seek to show people the severity of what humankind is doing to the natural world that we have, and how we are rapidly fucking it up.

In July, the Eden Project in Cornwall launched its 2019 arts programme, showcasing pieces it says are inspired “either by the Eden Project’s surroundings or by the narratives that the Eden Project communicates including sustainability, climate change, biodiversity and the vital relationship between plants, people and resources”. These include works by artists including Ryan Gander, Jenny Kendler, Julian Opie and Tim Shaw.

However, it can’t be denied that both individual art-making and the art world itself as a wider, nebulous body undoubtedly contributes a hell of a lot when it comes to bad environmental practices—from the materials for artworks, to where the money comes from to fund the arts (such as BP’s sponsorship of Tate, which ended in 2016, and incited numerous protest actions); to artists, organizations, and yes, us journalists clocking up carbon footprints flying around the world to exhibit, sell and see art. In short: art, even that which discusses the climate crisis, is problematic.

“It can’t be denied that the art world undoubtedly contributes a hell of a lot when it comes to bad environmental practices”

Olafur Eliasson’s current Tate Modern blockbuster, In Real Life, presents a retrospective that spans his career and showcases his preoccupation with the natural world and environmental concerns. While much of the work on show is based more around joyful, bombastic spectacle than serious message (though no one can deny the pleasures of journeying through 2010’s Din Blinde Passager, a thirty-nine-metre-long corridor full of dense fog that does very strange things to the way your eyes see colour and experience depth perception), much of his work—such as an ongoing photographic series showing the decline of Iceland’s glaciers—looks to alert viewers to urgent environmental issues.

Eliasson certainly seems aware of the contradictions around making such potentially environmentally unsound, bombastic works; frequently offering solutions as well as making work that highlights problems. These include his Little Sun project, which provides solar-powered lamps and chargers to communities without access to electricity; Green light – An artistic workshop, in which asylum seekers and refugees worked with members of the wider public to construct Green light lamps and took part in accompanying educational programmes; and Ice Watch, an installation of glacial ice from Greenland recently staged outside Tate Modern and Bloomberg’s European headquarters to increase awareness of the climate emergency.

In July this year, Tate released a statement announcing that its directors are “declaring a climate emergency” and that it is “committed to reducing its carbon footprint by at least ten per cent by 2023, and is switching to a green electricity tariff across all four galleries”; as well as offering “greater emphasis on vegetarian and vegan choices” in its food offers and adopting a train-first policy for travel. In a bid to amplify the concerns of the living artists it works with, Tate said it “will interrogate our systems, our values and our programmes, and look for ways to become more adaptive and responsible”.

“In July this year, Tate released a statement announcing that its directors are ‘declaring a climate emergency’

- Michelle Tylicki, still from the animation Catch about the fishing industry, 2010

It’s certainly a step forward; though some artists working at the literal frontline of climate activism would argue that large arts institutions like Tate, including the National Portrait Gallery, Royal Opera House and Royal Shakespeare Company (which are still sponsored by BP), are inherently problematic in that their funding frequently relies on sources that are less-than-environmentally sound. Michelle Tylicki is an artist and activist working across various media to campaign around climate crisis and social justice issues; and says that people need to “creatively and playfully challenge corporate and state power”. She adds, “there’s a lot going on in the underground in non-institutionalized, non-commercial spaces. People need to seek out and support those autonomous art spaces and look away from the mainstream.”

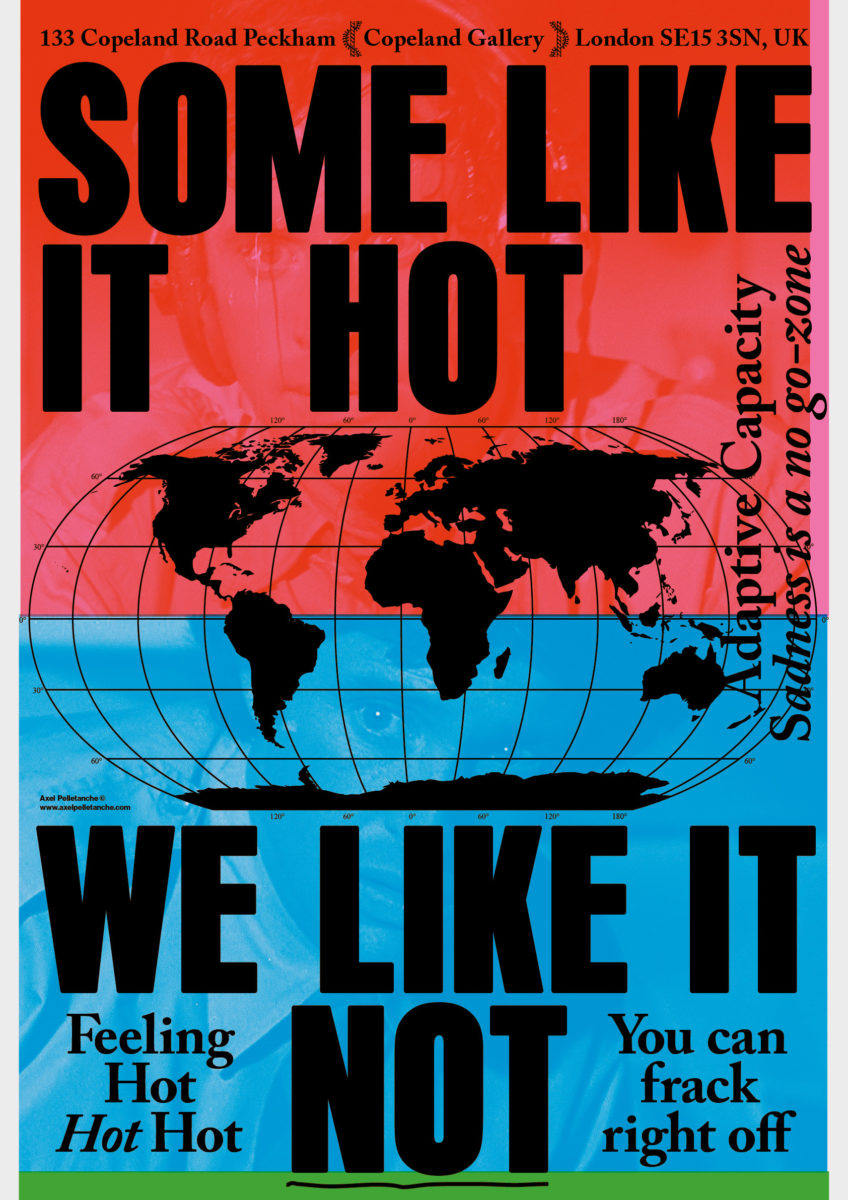

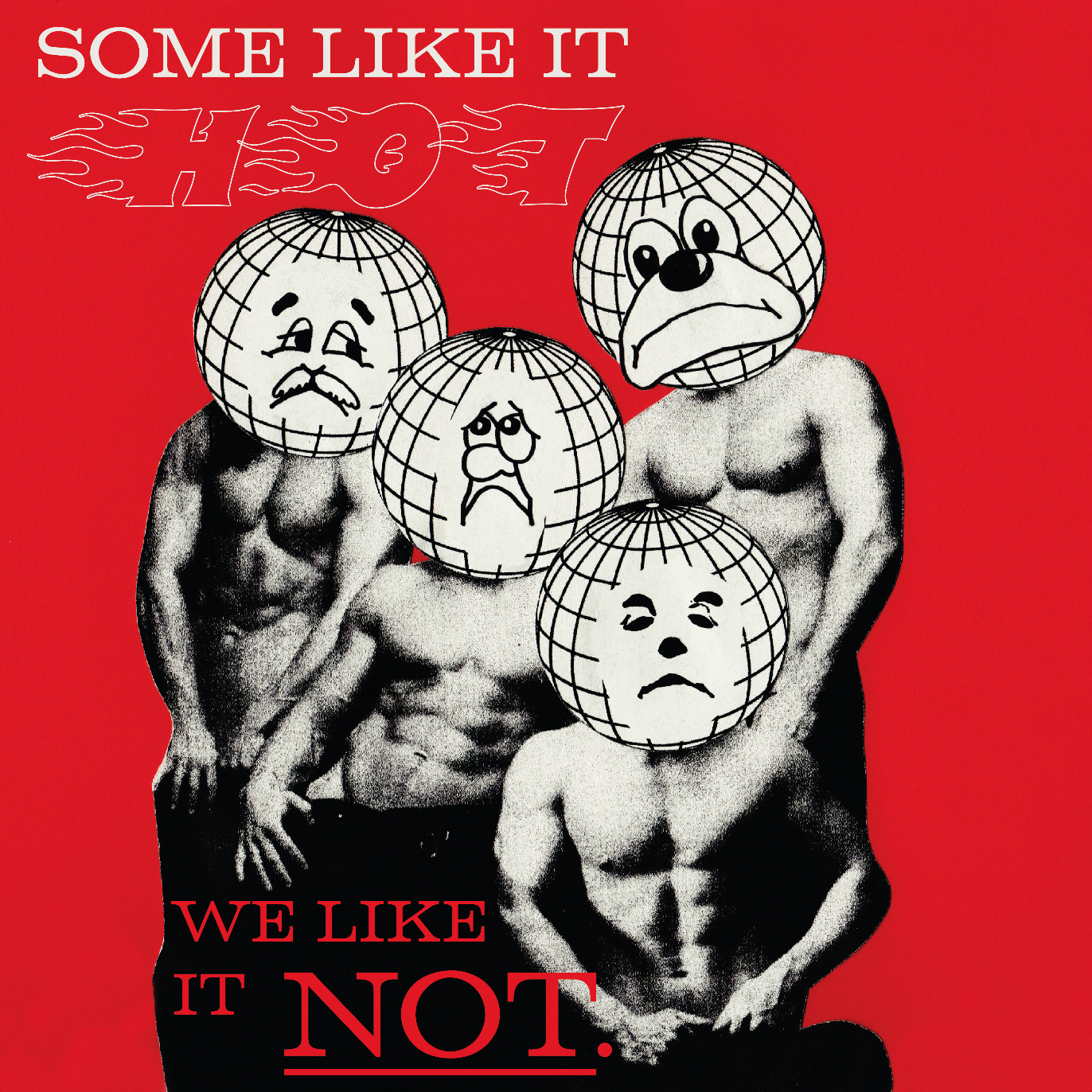

An exhibition earlier this month at the Copeland Gallery in Peckham, South London, titled Sadness Is a No Go-Zone, aimed to raise awareness of issues such as energy sources, the impact of travel and re-wilding through the lens of creativity. The idea was also to promote works that move away from communicating climate issues in a “gloomy” and “uninspiring” way; instead looking to showcase work that inspired “us as creatives who wanted to take action”, say Josie Tucker and Richard Ashton, creative director and producing director respectively of environmental group Adapt, which organized the show.

The pair attributes the dramatic rise in creative responses to climate issues in recent years to the publicity surrounding the likes of Extinction Rebellion, Brian Eno’s climate change-based NTS mix and the activism of Greta Thunberg. “‘Sustainability’ has been a sort of trendy buzzword for much longer, but it hasn’t meant people really talk about climate change,” says Tucker.

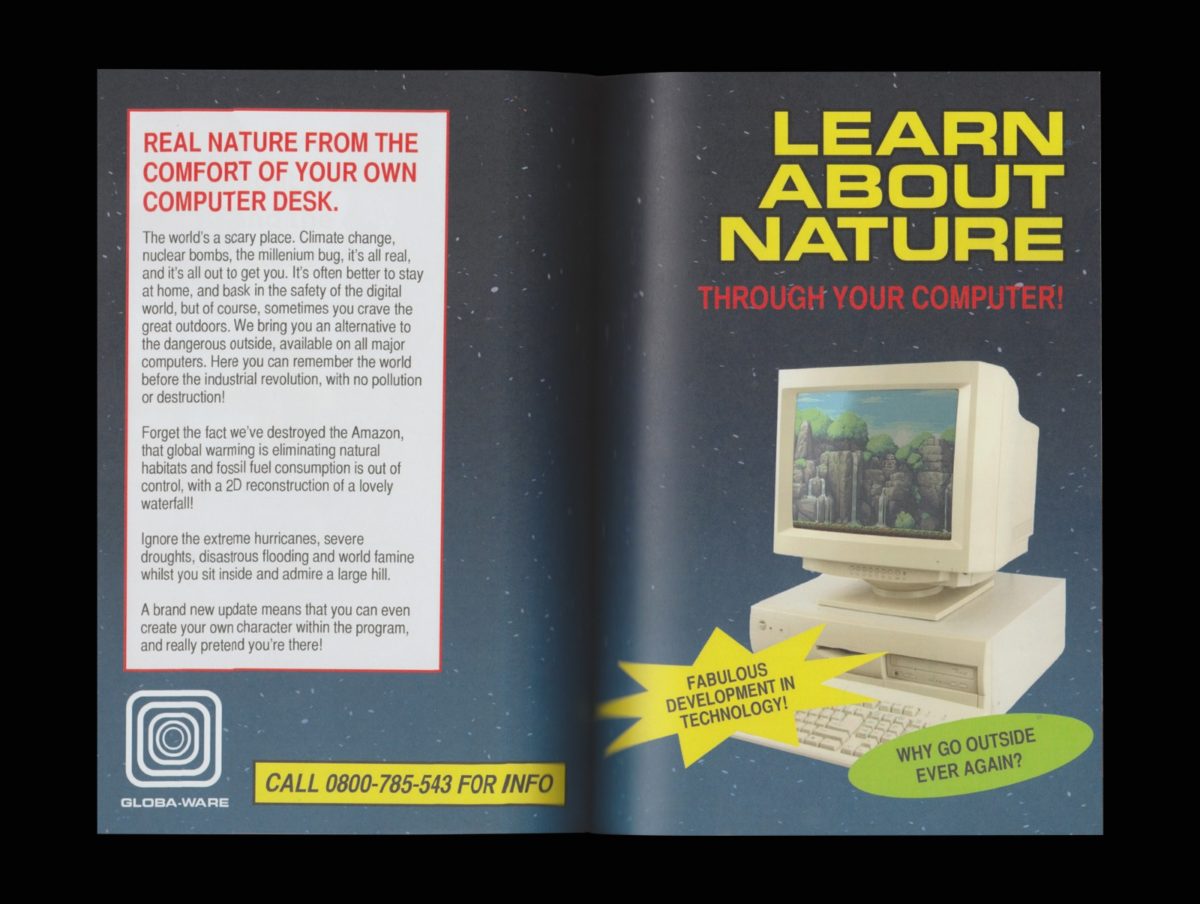

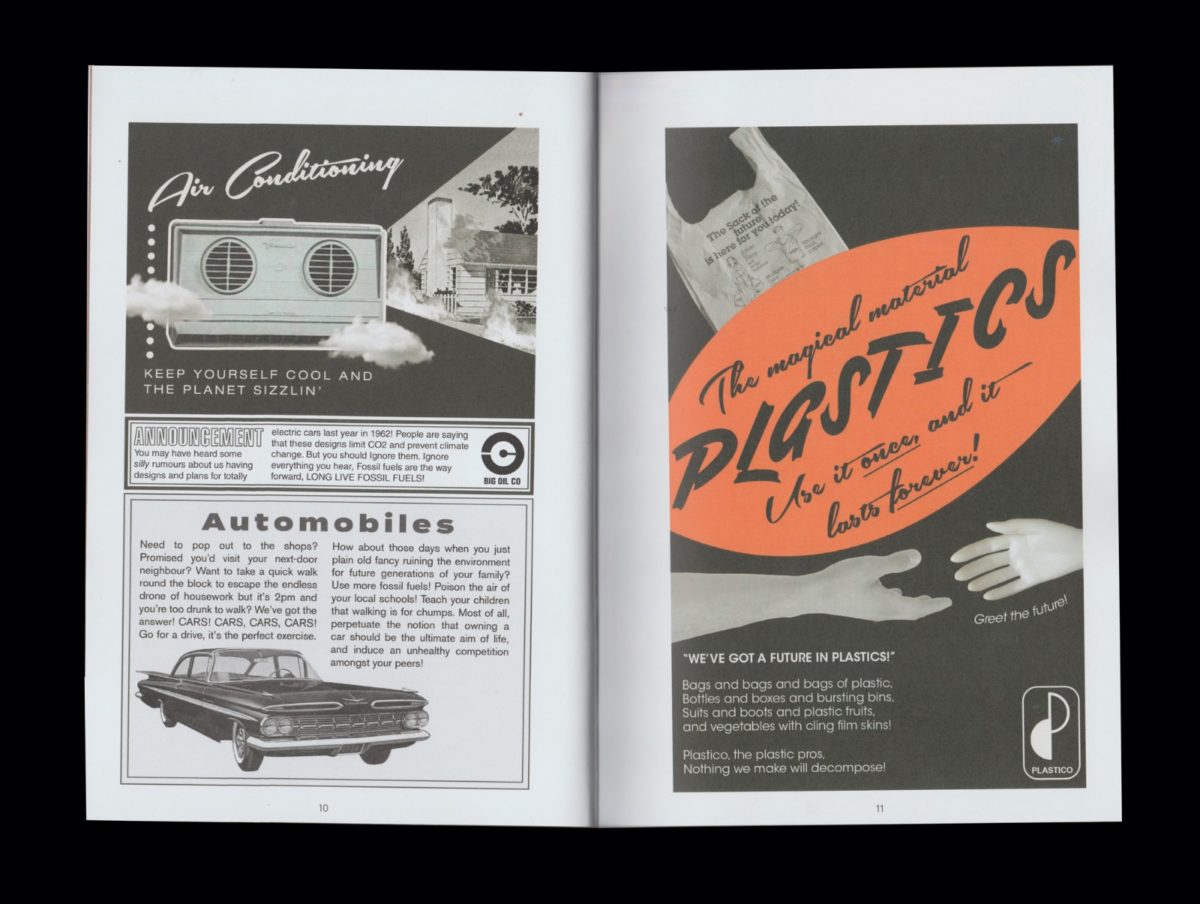

Ashton adds that the show wanted to “build a community who can showcase their creativity and talk about the climate crisis in an accessible way which makes people laugh”. As such, many of the pieces use puns or “silly work”, as Tucker puts it, to combine active engagement with issues and education within a space where people “don’t feel pressurized, blamed, confused or overloaded,” she says. “We needed to simplify these issues and create a happy, joyful space where any conversation is welcome and people have a good time.”

“There’s a lot going on in the underground in non-institutionalized, non-commercial spaces. People need to seek out and support those autonomous art spaces and look away from the mainstream”

Humour also plays a major role in art created for direct action. Tylicki’s performative work, such as her MA performance piece which addressed the wearing of fur, looks to use creative ways “to intrigue people. So instead of being shouted at about an issue, the audience can take the step towards me and assimilate my message a lot more easily”, she explains. “The language of art is so important in communicating important issues, and that resonates throughout my work, whether that’s graphic design for subversive advertising (subvertising, or ad-hacking) anti-capitalist campaigns, or direct action like climate wrestling clown rebel street theatre.”

In short, “climate wrestling clowns” comprises a troop called the RenewRebels who work according to a non-hierarchical, collaborative, anarchist-based structure built up of people with various specialist skills (wrestling, clowning, visual arts production and so on). The idea was set in motion by Tylicki four years ago as a “decoy” or “creative distraction group” organized by Reclaim the Power, a UK-based direct action network fighting for social, environmental and economic justice. “Doing something silly and playful like wrestling is always a useful de-escalatory tactic with the police; at the often tense and heated frontline, if you put on an entertaining and witty show, they’re less likely to hit you,” she says.

Since that initial wrestle, the group has polished the stunt into choreographed physical theatre, with actions including an unsanctioned show outside Barclays in Piccadilly Circus to highlight the bank’s role as the main shareholder for the company that supports fracking, and more recently at the Extinction Rebellion London blockades. “We’re trying to convey that there’s a real alternative to fossil fuels, through the powerful medium of silliness and educational yet cheeky slapstick acts,” she says. The public nature of such stunts means that it puts pressure on the bank, but also creates “accessible and free theatre for people who otherwise wouldn’t find themselves a part of [theatre], which is often quite exclusive and definitely part of a class system”.

“We’re trying to convey that there’s a real alternative to fossil fuels, through the powerful medium of silliness”

But for all their jolliness, at the heart of these more grassroots art practises is a direct call-to-action: Sadness Is a No Go-Zone featured spaces in which people could email their MP about taking action on climate climate using pre-written templates; and another where artist Peach Doble ran workshops for making protest flags (which are more sustainable than placards since they can easily be folded, stored and reused).

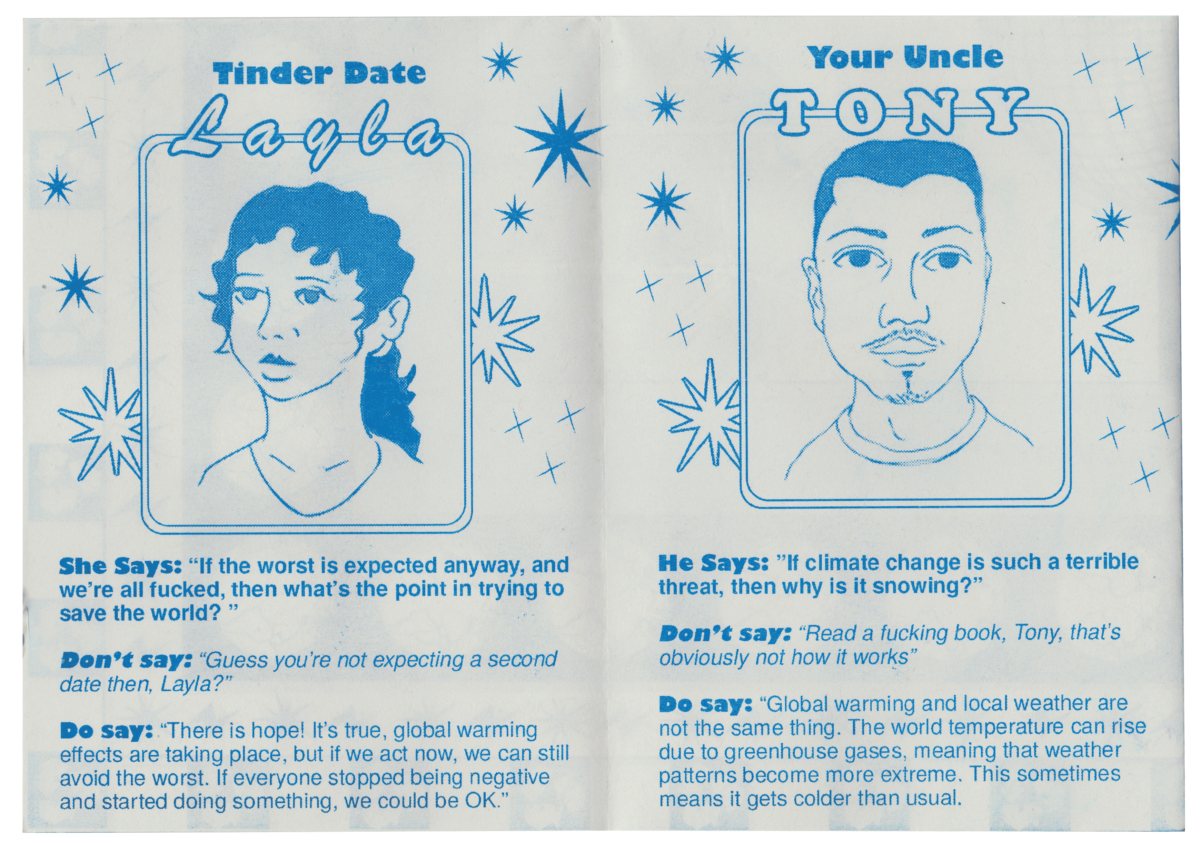

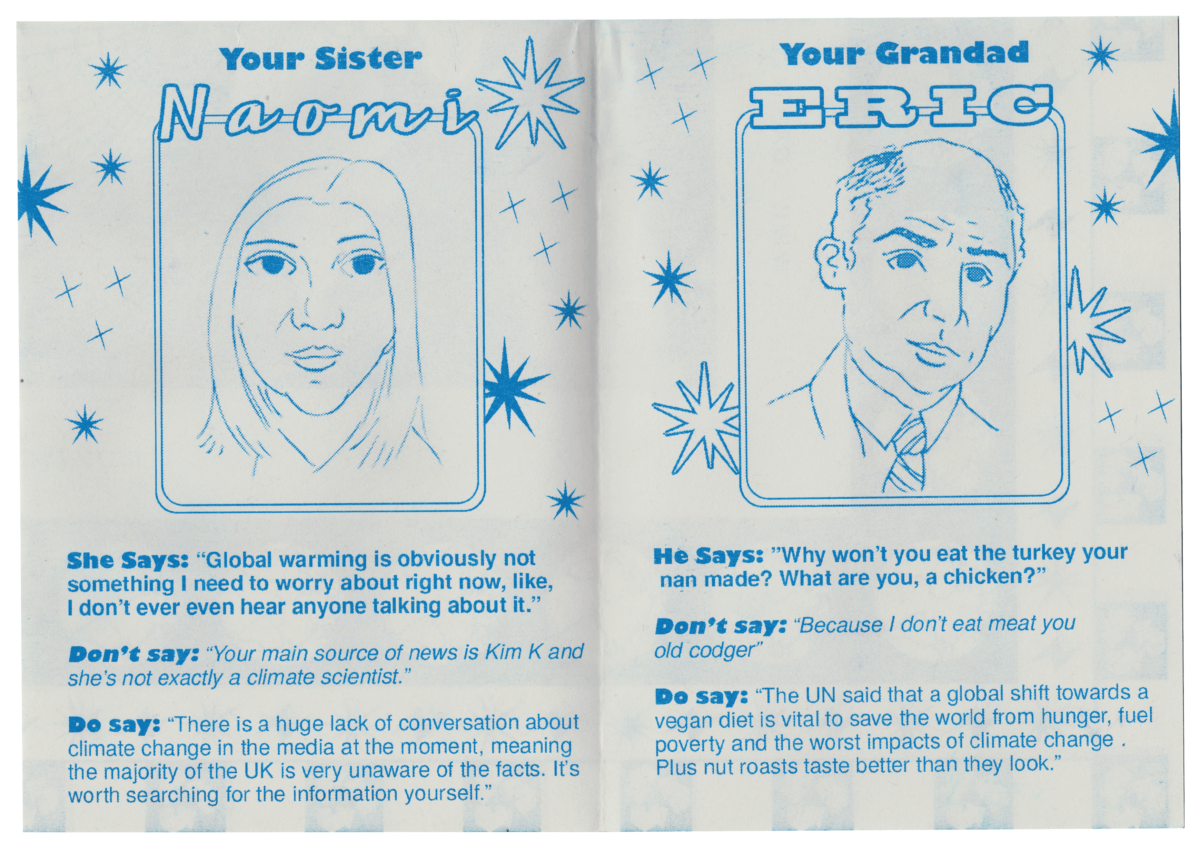

Much of art’s power in addressing climate change lies in the democratisation of complex scientific ideas to make them accessible. “It’s almost impossible for people to have a full grasp of what’s happening, but you don’t need to know everything to have a valid conversation,” says Tucker. Ashton adds: “The messaging is as accessible as possible—we don’t want to get too technical but we’re not dumbing it down. We want to offer little nudges for people on how they can do something in their own way.”

- Adapt - Climate Conversation Party Guide

Art also has the unique power to elicit emotion in people in more potent ways than, say, statistics or news broadcasts. The US-based group Artists and Climate Change was set up by playwright Chantal Bilodeau as a community of artists working across various disciplines making work around climate crisis. “In art, people are validated in their sense of loss and grief around climate change. Art can help them hold those—as well as give them a sense of possibility,” says Bilodeau. That sense of hope is another component in Tylicki’s work. “A big part of what I do is a sort of visual utopian style, so themes around envisioning a better future to make people realize we already have the solutions, we just need to combine forces to fight current power structures until they are implemented.” she says. “I wanted to inspire people to take action.”

“Much of art’s power in addressing climate change lies in the democratisation of complex scientific ideas to make them accessible”

While the climate crisis is certainly at the top of many artists’ agendas at the moment, sometimes, this is seen as little more than “woke-washing”, as Tylicki terms it, rather than actual moves toward change. Could it all soon be just another watered down #feminism? “I’m hoping we’re going to see discussions around climate change embed into what we do and see some significant changes,” says Bilodeau. “It should be something we think about all the time in the art world, in the same way that we’re thinking about things like diversity and disability.” I put it to her that there’s still a long way to go when it comes to those issues, too. “That’s true,” she says, “but you’re much quicker to call it out now.”

As for what artists can do in their own practice if they’re looking to be more environmentally sound, Bilodeau advises that “you have to make people feel like they’re not alone, and that their actions matter. It’s easy to feel like what you do individually has no impact; but if your art can encourage people to come together, we can do so much more collectively.”

Tylicki, meanwhile, says that artists (and indeed everyone) “need to be radical” about their approach—“which essentially means grasping something at its root”. This involves taking responsibility, and actively researching how the work you make can be altered; so a printmaker switching to Risograph printing (a greener alternative thanks to non-toxic vegetable based inks, its lower power consumption and zero waste); or a freelance artist looking into how ethically sound your clients are, and actively turning down work from those who aren’t. “You can challenge every aspect of your work,” she says. “It’s about being a practical idealist. Try to question everything.”

- Adapt, Parody Adverts for Syrup Magazine

What Artists Can Do To Help

- Look into switching energy suppliers. According to Tucker, even if you’re renting you have the right to do so, and greener suppliers include Bulb, Good Energy and Octopus Energy

- Consider switching banks: Tylicki advises that Nationwide, Co-operative and Triodos are among the more ethical companies

- Make work using environmentally friendly materials such as recycled paper (G.F Smith’s Extract paper is created from recycled coffee cups) and vegetable-based inks

- In publication design, consider creating pieces that can easily be disassembled through means such as saddle stitching and staple binding

- Email your MP to demand action on climate crisis (a template can be found here)

- Lend your creativity or support to existing causes and action groups such as BP or Not BP?; subvertisting groups Subvertisers International and Special Patrol Group; art and design climate club Adapt, or direct action group Reclaim the Power