In Hannah Gadsby’s astonishing Netflix special, Nanette, the comedian speaks with a voice seared with pain, anger and passion about her life growing up in Tasmania in the eighties and nineties as a lesbian in a homophobic society. She talks about her personal experience of sexual and physical abuse and rape. She talks of the shame she harboured over being “not gender normal”. “You learn from the part of the story you focus on.” She implores. “I need to tell my story properly.”

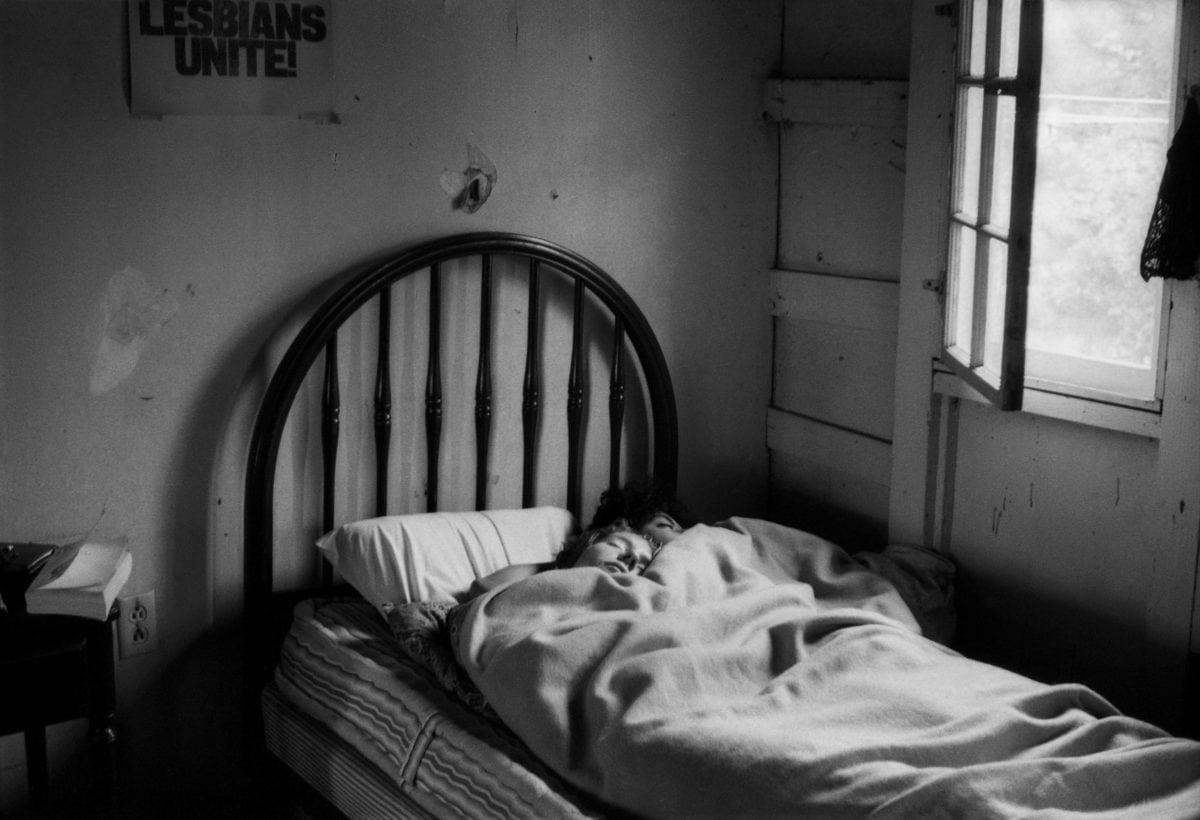

Donna Gottschalk’s photographs of radical queer and gay people in New York and San Francisco—friends, lovers, family members, people she was emotionally attached to—tell a personal story that, like Gadsby’s, was never properly told. Gottschalk grew up in a very poor family, in the impoverished Lower East Side of New York in the fifties and sixties. She realised she was a lesbian aged fourteen, and aged eighteen she joined the Gay Liberation Front, a political organization, and created their iconic and now well-known Lesbians Unite poster. In 1970 she moved to Washington with her girlfriend Joan Biren, taking photographs for radical feminist publications; a year later she moved to San Francisco, where the lesbian-separatist movement was gaining momentum. In the mid-1970s she returned to New York to help her gay sister and her brother, who transitioned in his forties—documented by Gottschalk. Both siblings sadly passed away while still in their forties.

Gottschalk’s photographs speak of a turbulent time, personally and politically, for queer people. They find love in sadness and, like Gadsby, find the ultimate truth about humanity in resilience. “For over forty years I kept my negatives and photographs largely to myself, not wanting to subject them to the possibility of painful scrutiny or judgment of others.” she says. “Many of the people I photographed didn’t get much sympathy in the world, and I wanted to make viewers stop and really look at them and not pass them by.” Now is the time to stop and look. As Gadsby imprecates: “This is bigger than homosexuality. This is about how we conduct debate in public about sensitive things.”