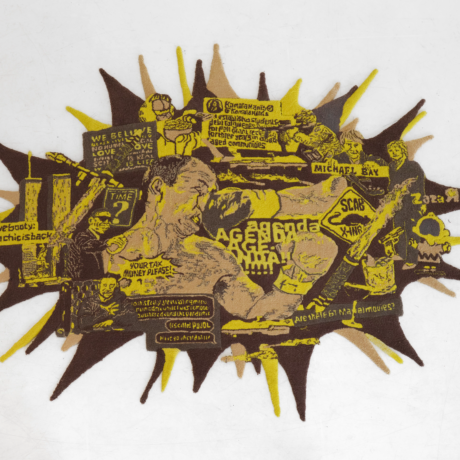

London- It was during the final year of her master’s degree that Heather Agyepong first felt compelled to turn the camera on herself. She had travelled to Ghana to research her dissertation topic: The Misrepresentation of West Africa as Dystopia, and the trip was transformative. The key focus was an e-waste site on a former wetland called Agbogbloshie in the centre of Accra. Electronic waste from all over the world is dumped there, and young boys – often young Muslim boys – burn discarded tech products to extract their precious metals so they can sell them. The place has a reputation for being hellish – rampant crime in the area earned it the nickname ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’ – after the bible story about the cities that God destroyed for their wickedness.

Agyepong describes an experience that could not have been further from the tropes she’d read about in the mainstream media. She recalls being treated with the most amount of care. During her conversations with young men working at the dump site – some of which were in Twi, the native language of that region and Agyepong’s second language – she discovered the sordid truths about the creation of the award-winning photojournalism projects. The boys told her stories of heavy exploitation from White western journalists who photographed them and promised them money, asked them to pose with items on their heads or to rub dirt on their faces, and then disappeared. As part of the project, she stayed in the area for six weeks and spoke with the people she met about how they wanted to be depicted. The result was The Gaze on Agbogbloshie, a series of images in a ‘kind of metal blue’ about how whiteness is destroying that community.

Though the project was well received (Agyepong passed her MA with Distinction) Agyepong was unsure about her future as a photographer. “I found the idea of me being a photojournalist very reductive,” says Agyepong. “The project was about learning and unlearning what it means to be Ghanaian. It was about how I saw Ghana, these ideas around self-hate, and the embarrassment of being from Africa. I was trying to deconstruct where that came from and realised it’s because I saw images like this.” This was around the time she began to understand her photography as a tool for reflection and self-discovery. So she decided to switch the camera around. Since then, all of Agyepong’s work has been self-portraiture. “I’m just not interested in taking photographs of anyone else. It has to have some catharsis – if I’m not doing that, the photos will be dead. All I care about is understanding me better – that’s my single motivation.

Agyepong’s first solo photography exhibition, ego death (title styled lowercase), started as a lockdown project about community. When deliberating the details of the proposal she wanted to submit to the Jerwood/Photoworks commission opportunity, her mind was full of thoughts of the feeling of unity. She had become taken with the random acts of neighbourly generosity witnessed at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and, in particular, the ways in which people went above and beyond to help strangers. “The depiction of community didn’t seem like it existed before COVID. Like, people just helping neighbours. I just thought it was really beautiful. And my fear was once COVID is done, that will be gone”. She wanted to memorialise the moment for posterity and began to follow the question: how can I reimagine myself as this kind of spirit of the collective?

During the application process, her confidence was challenged by the fact the initial idea was not fully formed. But she was encouraged nonetheless to submit a proposal because of her profound trust in the commissioning partners. Her solo theatre show The Body Remembers (2021) was part-commissioned by Jerwood Arts, so there was already a healthy existing relationship. “They’re really interested in nurturing creatives and developing their practice.,” she says. “It’s not always about the outcome – it’s about developing the artists’ career long-term and giving them confidence”. She recalls feeling massively intimidated by the level of sophistication in the work of previous winners. “Everyone who’s won before had been quite clear in their vision, and I wanted to do something different”. Italian artist Silvia Rossi particularly stood out. “She’s this Toglogese artist, and she just really knew her practice…I was not confident at all”. Part of that is to do with a lack of access to aspiration. For Agyepong, the fact that she is a multidisciplinary artist is a significant part of that – it’s difficult for her to find the proverbial footsteps to follow. Despite this uncertainty, she was absolutely sure that she would regret not putting her hat in the ring for the lucrative commission and sent in her application on the day of the deadline.

Agyepong has been working professionally as a multidisciplinary artist for a decade now. As well as a solid photography practice, she is a successful actor across stage and screen. She is currently performing on stage in London in the UK premiere of US Playwright Jocelyn Bioh’s School Girls: Or, the African Mean Girls Play, and earlier this year, Amazon Prime released its adaptation of Naomi Alderman’s The Power, in which she plays one of the lead characters. She graduated with distinction with an MA degree in Photography & Urban Cultures in 2014. Two years later, she won a major Autograph ABP/Heritage Lottery Fund commission to create Too Many Blackamoors. More commissions followed – notably from Hyman Collection and Tate, amongst others. She has an agent and regularly sells work – Arts Council England just acquired seven pieces from her ego death series. ego death will also be part of a group show titled I See the Face of Things to Come by guest curator Renée Mussai as part of Photo Irelands Festival 30th June – 27th August.

But when asked if she considers herself an established artist, she’s tentative. “When I think about established artists, sometimes they’re in their 60s – like Carrie Mae Weems – people who have been doing this for years and years”. She cannot conceive of the idea that she could float among the august ranks of an artist so prolific. Asked if she feels like an emerging artist, she replies – “I don’t know”.

Ultimately, she finds many of the traditional definitions within arts industry parlance unuseful. At the same time, she won the Jerwood/Photoworks Award, she also won the Photographer’s Gallery Emerging New Talent Award. “It’s very confusing – one gallery says I am definitely emerging, and the other says I’m established – so I don’t know how to talk about myself. It’s not great for the long term because you don’t know what to do with that. Sometimes I feel like a baby girl, but then I’ll get people wanting to be mentored by me. I’ve got no clue! But then, do I? I’ve actually got a lot of commissions. Do you see what I’m saying? Yeah, [the definitions] are not useful”.

There are some traditions, though, that play on Agyepong’s mind. When talking about her route to success, her repeated use of the word unusual is notable. “People in the art world love tradition. They need art schools to be the place you go to learn to be an artist, and if I’m like ‘nah babe, I didn’t really do that’, it messes up that sort of idea”.

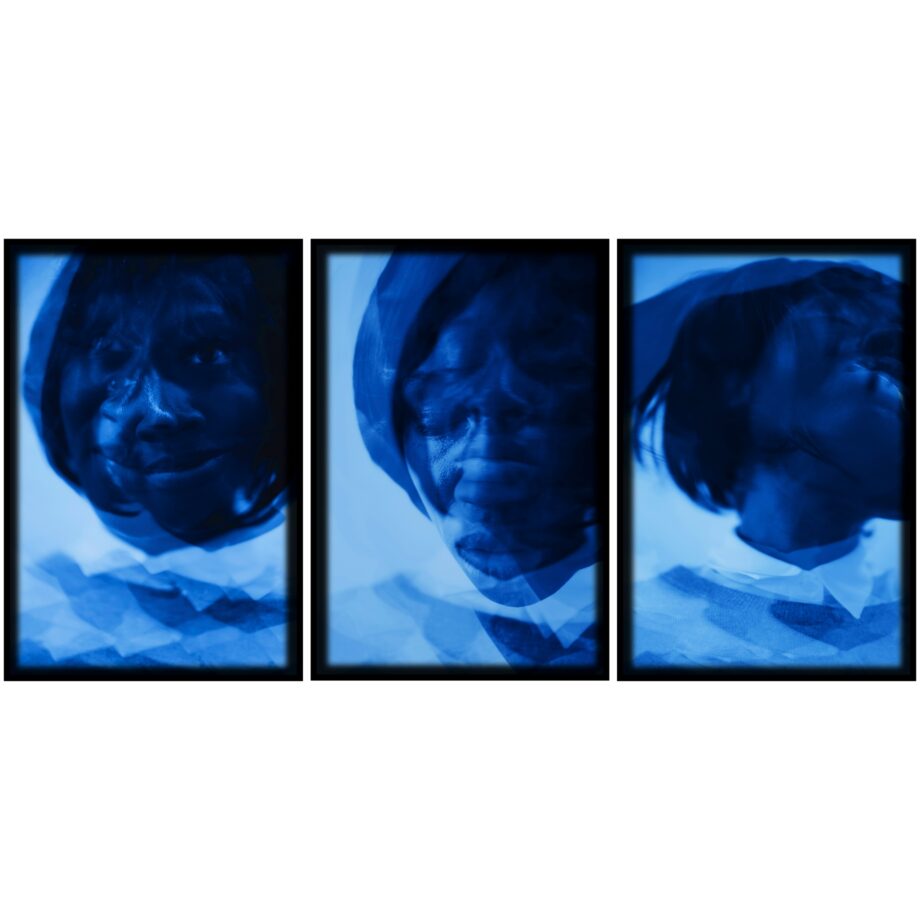

ego death is Agyepong’s most intimate work to date. “It’s parts of myself I’ve either ignored or feel shame about,” says Agyepong, “and I really want to look at those parts. That’s why it feels the most personal because some of these things I didn’t even know they existed in me. Or I was embarrassed or ashamed to acknowledge them”. The work is inspired by Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow. Jung believed that to compensate for traits that we have that have been deemed unacceptable by our peers and family members, we create characters that are polar opposite to those traits. “All this is about being loved and accepted. Whatever behaviours you’ve been told will make you more loving and accepted are the ones you adopt”. Agyepong stresses the importance of doing this work alongside a professional therapist and would urge anybody interested in exploring their own shadow to practise psychological safety while doing so.

Through the process, she identified seven different characters, which are the subject of a series of photographs in the exhibition: O Daughter, Saboteur, D is for…, Georgina, Lot’s Wife, and Only Pino. She discovered these characters through Jung’s concept of accessing the unconscious – lots of free writing, free drawing and unrestrained movement. “Every time I feel fear or a deep emotion, I think, OK I am getting close to the shadow. Let me write something”. She explains that the shadow wants to be hidden, so anytime you feel fear or shame – states of emotion that are typically very uncomfortable – that’s the time the shadow is speaking. For the seventh character, Somebody Stop Me, Agyepong poses with a mask. This, she says, represents the choice she now has, having identified these elements of her shadow, of whether or not she’ll allow them to take over.

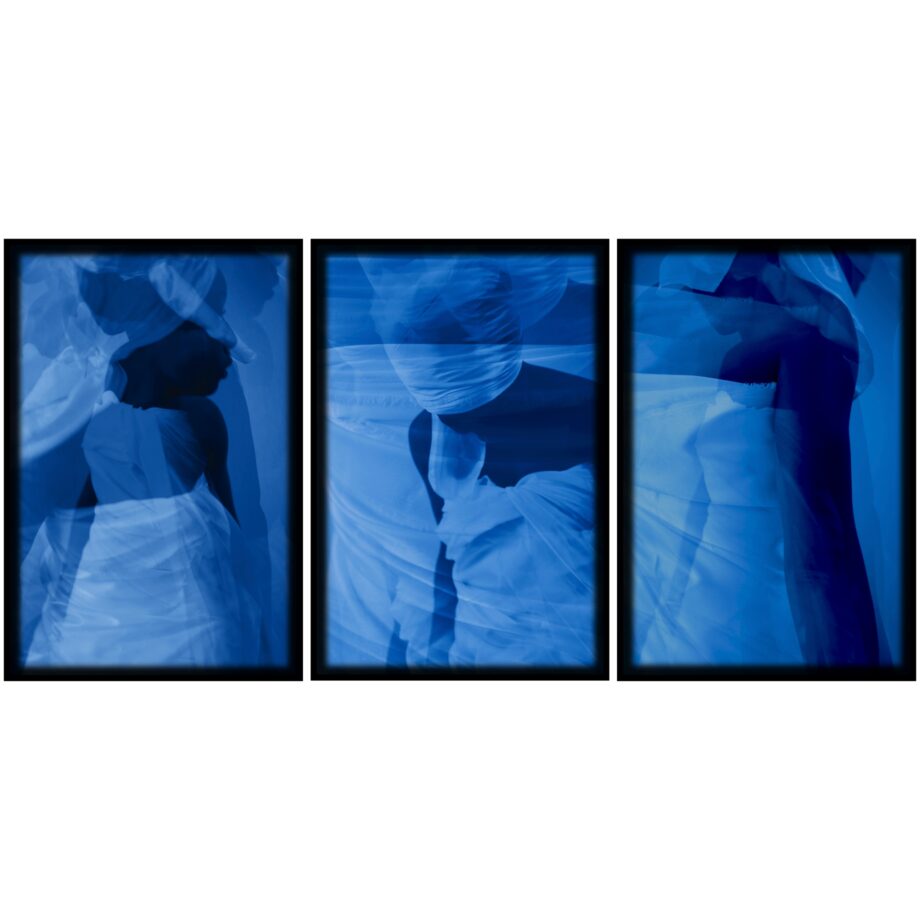

Each of the characters is displayed as a triptych, and choosing the final images for the exhibition was a monumental task. Agyepong notes: “There were so many images it felt like a lie to have just one representation for each character. All the images are double exposure, so there are two images in one, but each image is moving. Something about movement felt very important”. In that respect, the work is a continuation of The Body Remembers, where accessing the unconscious happens by allowing the body to speak through movement. “I’m allowing my body, my mind, my whole being to speak – especially the repressed shameful parts”. The sequence of images taken for each character felt like it was articulating some sort of narrative – “not a beginning, a middle and an end but definitely a significant moment in the movement journey of each character”.

One of the many striking things about the exhibition is the colour – the photographs are all printed in a blue scale palette. Agyepong enthusiastically talks about being inspired by the Barry Jenkins film Moonlight, but it’s notable that there is a similarity between this and her MA dissertation project, which was finished before the film was released. Agyepong admits she hadn’t consciously thought of this project being an evolution of that one but agrees that the essence of both is the idea of revealing truth. Jenkins’ concept of honesty and vulnerability coming out under the glow of moonlight was the reason she chose the colour blue. She wanted to nod to the power of truth-telling as somebody who wants to be more honest.

As ego death continues on its tour of the UK, Agyepong’s main hope for the work is that people engage with an openness to being affected by it. “I have quite deep experiences listening to Lauryn Hill’s album (MTV Unplugged No. 2.0, Live album by Lauryn Hill). She did a live performance of, I don’t know what song it was, she said there was a time when people thought she was ‘crazy’ and she responded by saying ‘I want to perform the thing on myself first before I give it to other people’ and that really resonated with me. I’m doing the work and I also want to show you – I’m where you are. In all my work, I Want to show the process of healing so people feel community and not ashamed [of their journey]. That’s what I want people to experience: less shame”.

Words by JN Benjamin