Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition, duo Elmgreen & Dragset reflect on two artists born 150 years apart, Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and American minimalist Donald Judd, and the impact of their respective explorations of the body and the built environment.

Michael Elmgreen: I was first attracted to Bertel Thorvaldsen’s sculptures in high school. It was at the Thorvaldsen Museum, a beautiful building designed by Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll. They were so appealing with their smooth marble bodies. My family didn’t drag me to galleries and I didn’t have an interest in visual art, but I was fascinated in a way that was not intellectual but immediate and sensual.

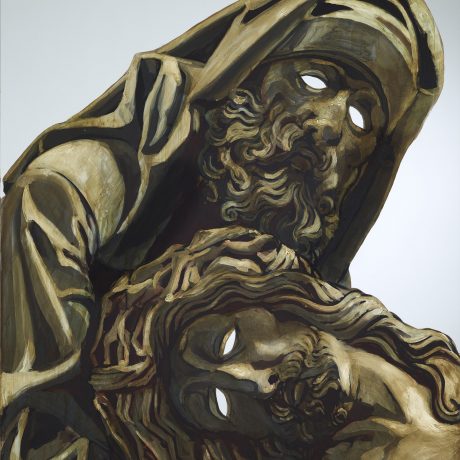

Ingar Dragset: We found it interesting to look at Thorvaldsen from a queer perspective. There is no proof of him being bisexual, and he certainly had a lot of women in his life, but there was an eroticism to a lot of his work. We wanted to look at it from a contemporary perspective, from our perspective.

When you put a jockstrap or a backpack on these sculptures, they suddenly look more relatable. In 2009 we made a series of works where we gave some of Thorvaldsen’s sculptures clothing. Thorvaldsen was very important to us from the very beginning of our collaboration, when the body was at the centre of our performance work.

ME: Thorvaldsen depicted masculinity in a very feminine way. We tend to think that historical sculptures all have a macho appearance, all warlords and equestrian compositions, but in both the Roman and Greek tradition (and neoclassicism) you had fewer heroic postures of the male body.

There was uproar over the provocative images Thorvaldsen created. Although he was celebrated at the height of his career when he came back from Rome, afterwards society became more prudish and sexually moralistic. He was quite erotically obsessed. He had a vast collection of pornographic sketches that he kept secret and didn’t show.

Thorvaldsen caused debate in his time and that’s something we can relate to. When we made our Little Mermaid-inspired, stainless-steel sculpture in Elsinore, Denmark, it caused an uproar. Han (2012) depicts a young man sitting on a stone in the same position as Edvard Eriksen’s original statue. People went crazy. How could the city commission such a gay sculpture? It really was a headline debate in the Danish context.

ID: What is so great about these reactions is that it shows people actually care about public space. That it’s a shared space. What we and many other artists have experienced with public art, is that once the sculpture is there and people really see it and live with it, they tend to take it to their hearts. They take a certain pride in it.

“People often use Judd’s work as a starting point to do something that is hostile and hyper clinical. But it’s not in his work”

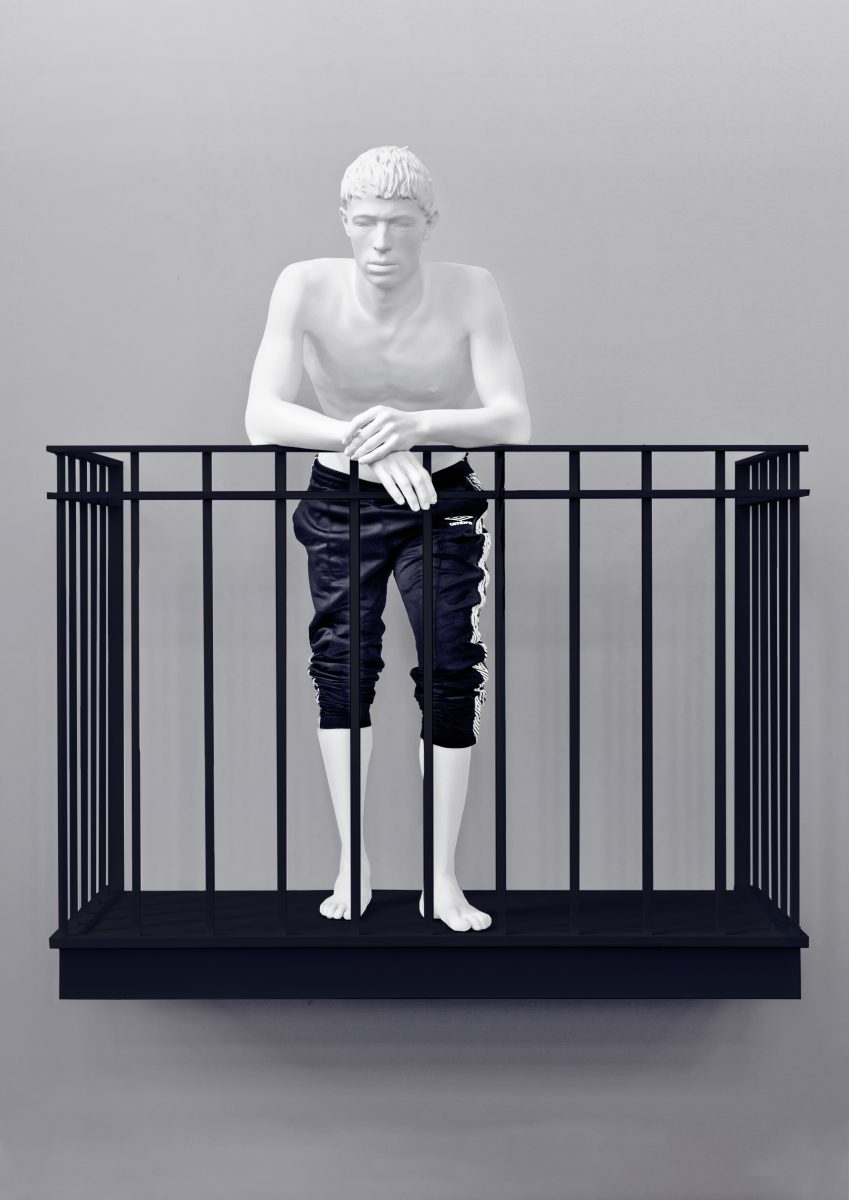

Elmgreen & Dragset, The Outsiders, 2020, installation view at Unlimited, Art Basel, Basel, 2021. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano. Courtesy Pace Gallery, New York

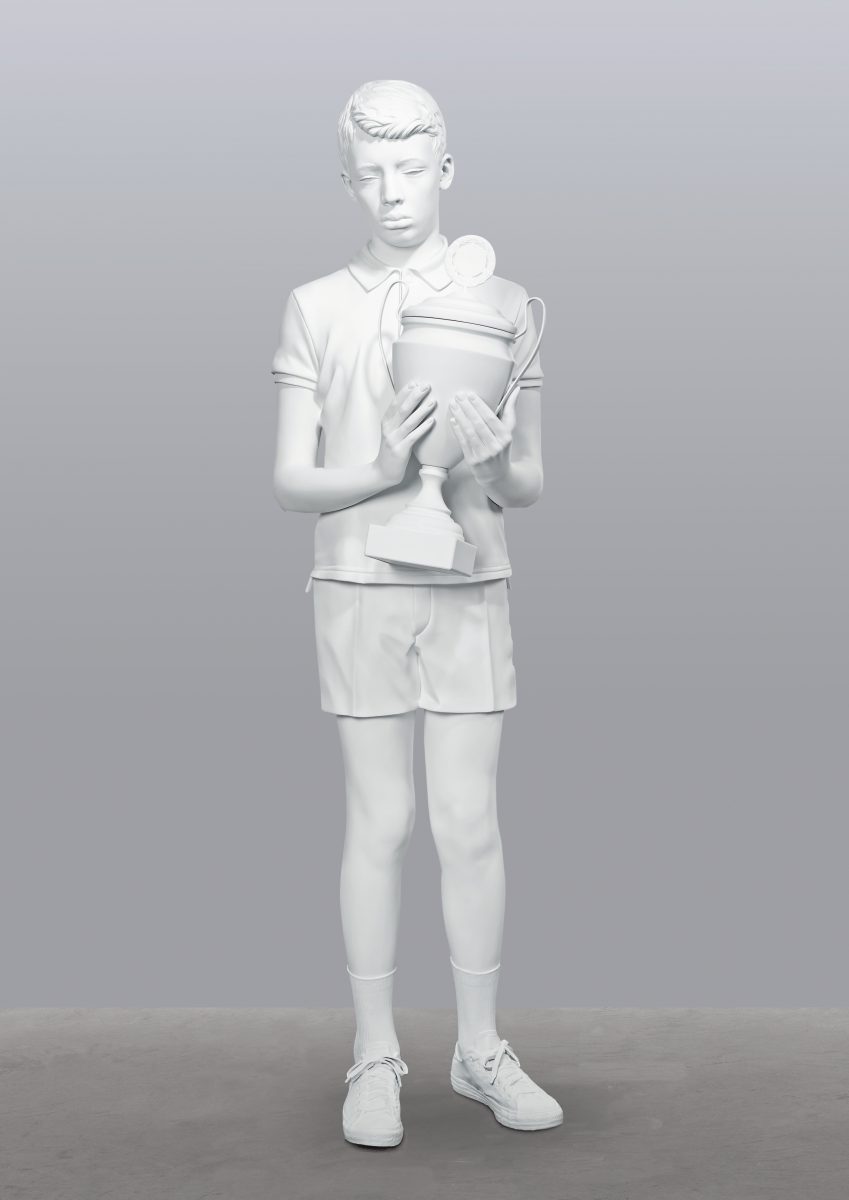

ME: We have explored the tradition of how the male is depicted in public sculpture many times. On Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth we had Powerless Structures, Fig. 101 (2012), a bronze sculpture of a boy on a rocking horse. It mocked the grumpy King George IV on the other plinth in front of the National Gallery.

Public sculpture is linked to the social fabric of the city and certain power structures. At that time, it was very important that we scared Boris Johnson, then mayor of London, away from inaugurating the sculpture.

ID: We don’t choose between a figurative, classically inspired or hard-edged minimalist practice. We combine the two, which is a kind of contradiction. Donald Judd is also a big influence. In many of our childhood bedrooms, there were bookcases that looked like Judd’s work, but we didn’t know it then of course. That kind of minimalism is injected into your upbringing in Scandinavia, even in nursery school.

“We don’t choose between a figurative, classically inspired or hard-edged minimalist practice. We combine the two, which is a kind of contradiction”

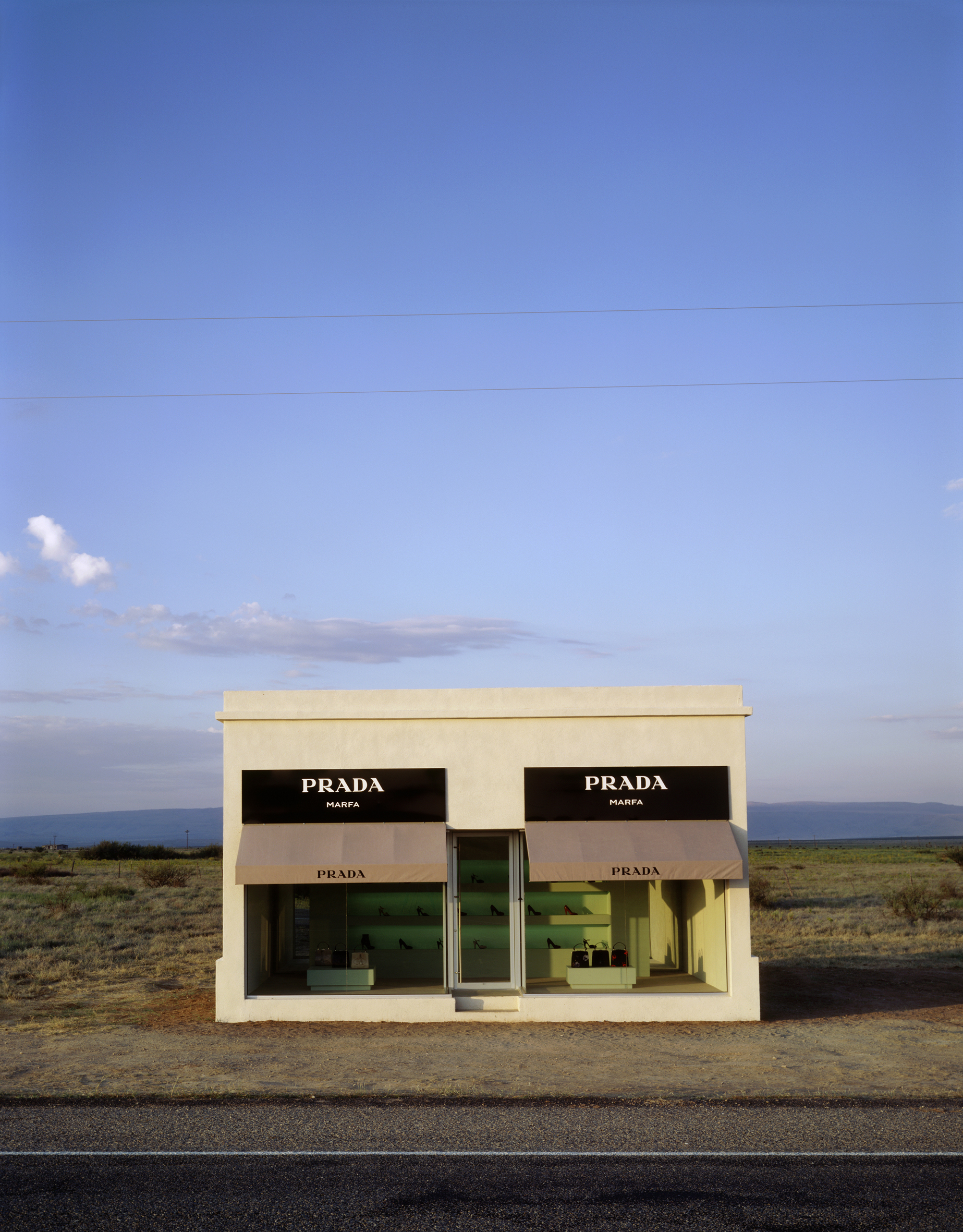

ME: We really got to think more deeply about him when we were choosing the location for Prada Marfa (2005), in the American desert, by Highway 90. In Marfa, you have the Chinati Foundation, founded by Judd. It’s Donald Judd town.

He has had a huge impact on contemporary sculpture and interiors, not least commercial ones. When we looked at the signature mint green Prada store shelving, we realised they would not have been able to exist without him.

People often use Judd’s work as a starting point to do something that is almost hostile and hyper clinical, where you would be excluded for any error and humanity seems to have vanished. But it’s not in his work. His starting point was to make a platform for social activity. The reading of his work as reductive is something that has come later.

Prada Marfa, 2005. Courtesy Art Production Fund, New York; Ballroom Marfa, Marfa; the artists. Photo by James Evans

ID: With our figurative sculptures we create little narratives. We imagine that figure’s life, an action that has just happened or is about to happen. Then you have our installation environments where you are completely left to your own devices, to make up your own idea of the story unfolding.

We are not very orthodox in either direction. We love to combine the two, and say hey, the world consists of both elements.

Emily Steer is Elephant’s editor

Elmgreen & Dragset, Useless Bodies? is at Fondazione Prada, Milan, until 2 August

Under the Influence

Discover the connections between today’s creatives and the artists who helped shape their work

READ MORE