Back in 2018, when I saw Em Rooney’s work in MoMA’s show Being: New Photography, I was struck by its tenderness. In the two years since the glimpses I’ve caught of her work have been online, as I’ve sought out her sculptures in their photo form, processing all their heavy materiality as pixels.

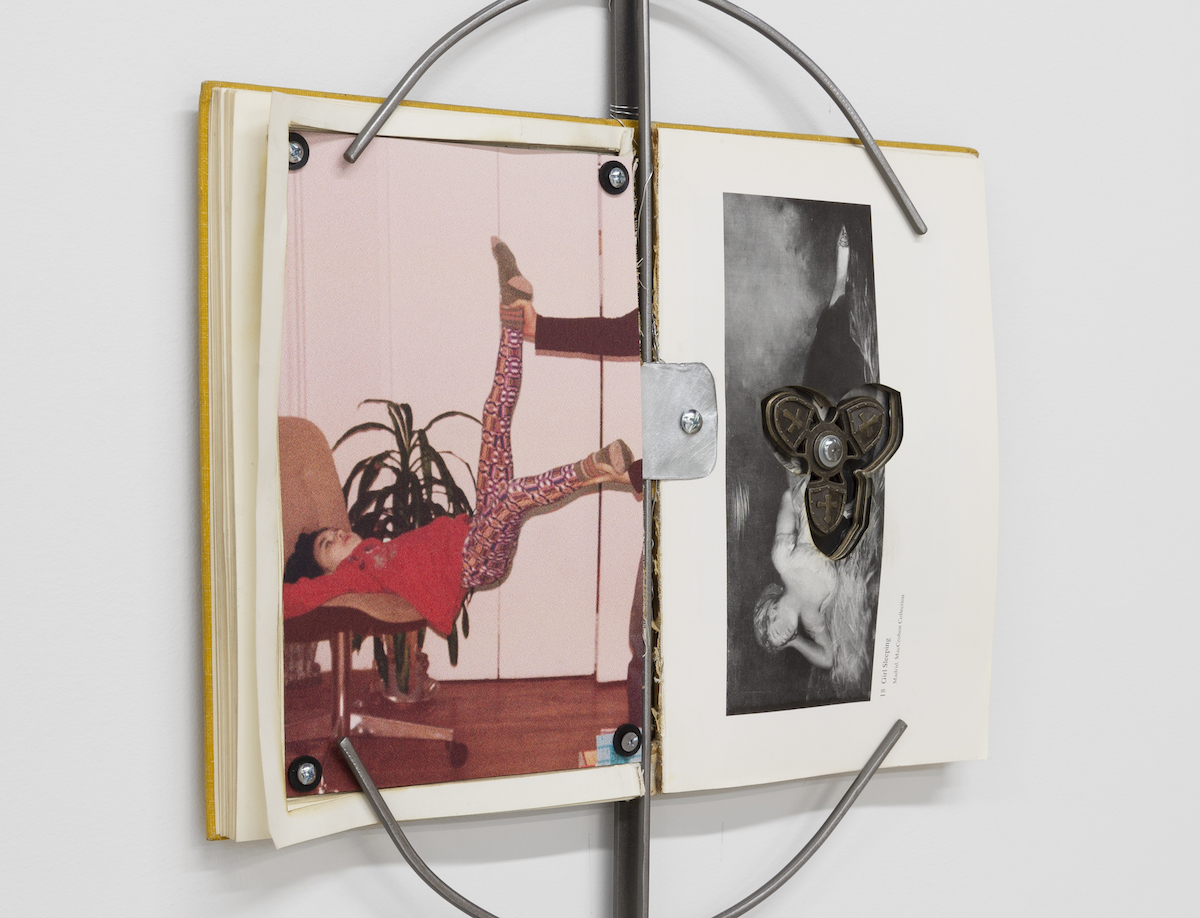

In Rooney’s practice, photographs are given a stillness that the images we scroll through online are not afforded. They are treated with care, enshrined in resin or dressed up with pewter; they are also weighed down, embedded in books or strapped to the walls with steel brackets. Rooney’s role as an educator (she has taught a range of subjects, including humanities and photography, for the last ten years) emerges in the material generosity of her sculptures.

Rooney had a solo show titled You, Too, Know That You Live at Galerie Fons Welters last year, and most recently exhibited in Bodega’s online viewing room for Art Basel. I spoke with the artist about the erotics of metalworking, taking personal photographs, and why photographic literacy is “key to survival”.

- Between (Girl Sleeping), 2018

In You, Too, Know That You Live you made multiples of works and gave them as gifts. What brought you to that as an idea?

My professor in college was the collage artist Robert Seydel. He was working in a moment where DIY and mail art was becoming an ethos of making. He was so charismatic and influential that this idea worked itself into my thinking from a young age: you could send something to somebody and the act of sending could be art; intentions and actions and things that are imperceptible, a feeling or a description of a feeling, could be art. That was really revelatory to me.

I saw this Julie Ault show in 2013. She had collected things that members of Group Material had sent to each other as gifts. It was amazing. It has something to do with the archiving of artists’ relationships, and people building their own universe between each other, through this kind of sharing that’s outside of the canon, outside a certain type of approval that you would get from capitalism or the art market. It’s anti-capitalistic, that’s what was so moving for me.

I’ve been making things for friends that I think of also as art for a while, but for that show, Tim Rollins’ project with Kids Of Survival was influential. Rollins had this ongoing collaboration with kids in the Bronx. It’s not always my instinct to work collectively with my students but I loved that idea: doing an edition of gifts was more a framework, a way to think about how to make a series of sculptures.

As an artist you’re always finding ways to situate your impulses relative to your work. So, even though there’s a lot of care and community-building in my practice (things outside of what I do alone in my studio), weirdly, that show is almost not that at all. It’s there and it helped me make that show, but the show is less about the intimacy of those objects and more of a way of thinking about how to make sculpture.

“Intentions and actions and things that are imperceptible, a feeling or a description of a feeling, could be art”

In the MoMA show you had a frame with text (Sarah with a Portrait of Her Own Eyes). What can a frame do without a photo in it?

That frame actually did have a photo in it, it was just turned to the wall. I think that’s an important distinction, because for my practice a frame without a photo doesn’t mean anything. What made that piece meaningful was that the content is latent; in there but invisible, like a piece of undeveloped film. It has a photograph, but it hasn’t come into existence yet, so the meaning is the way you know something is there but it’s not accessible to you, like an urn filled with ashes or a locket that doesn’t open.

That sounds really linked to desire. I’ve been reading Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet. Does that resonate with you, desire being a part of your work?

So much. In so many ways that I don’t even know where to begin. The first thing that comes to mind is a piece that I saw at Matthew Brannon‘s studio, probably in 2016: big abstract silk screens. The stretchers had slots inside them, and in each slot was a novel he had written, they were all pornographic novels. It connects to this idea of the envelope, which is a thing very connected to desire. You need to see what is inside it, you need to rip it open. I brought my students to look at our college’s artist’s book collection and Anne Carson’s Nox was there. It ended up being very influential on one of my students who wrote her final paper on Carson, the envelope and desire. A beautiful paper.

Anyway, definitely those Matthew Brannon pieces lodged in my brain and influenced some of these pieces I made that had text on the back. The text would be more honest and open than the piece itself, and it would be something very few people would ever have access to because the piece would never be shown from behind… except that it was at MoMA!

“That’s why I love working with metal, because it’s so much more like the body than wood or any other material”

When I was in a university class, the artist Kathryn Elkin showed us a film by Chick Strand called Soft Fiction. There’s a bit where a woman speaks about seeing a metal railing and having an erotic reaction to it, a desire to become the railing and to let her bones go soft. I was wondering what working with metal is like for you, if it’s connected to that?

That’s a really great comparison. I totally think about that, I’ve always thought about that. A while ago I made a zine with Good Press called Love Is In The Flowers, a bunch of photographs and a text I’d written about when I worked as a fabricator for a year. I worked in the metal shop, which was almost all women, and for a while it was just women. All three of us are queer, so it was about the phenomenology of working with metal and all the various incantations, what happens when you apply things to the surface and see chemical reactions, how it gets hot and how it bends, the erotics of using the drill press.

And there was this really charged, kinetic feeling because of the crassness or rawness that can happen when you’re working with your community members and it feels really safe—this queer female-bodied version of shop-talk, relative to these really strenuous material things we were doing. That’s why I love working with metal, because it’s so much more like the body than wood or any other material.

- The Risk of Being Left Behind, 2017

I read that your practice works “against the ubiquity of the photograph”. What does that mean to you?

So much of our engagement with the world is through photographic, pixel-based images. All day we’re interfacing with pictures, so I’m talking about that. Traditional processes can get discussed in relation to nostalgia, but I don’t relate to them in that way. I really think about the material world: things that are yours and things that you can hold, things that aren’t held hostage by corporations, which so much of our image content is now, even when we make it for ourselves. And because of photography’s historical and contemporary ties to imperialism, colonialism, oppression and racism, there are so many nefarious uses for photography, and many are related to its current ubiquity.

Fighting against this ubiquity is learning to take photographs that are nuanced and self-reflective and actually personal. I don’t mean personal like taking photographs of your loved ones necessarily. The past five years I’ve been photographing people on the street with my camera, which I used to feel uncomfortable doing. It’s about how to do that while holding the history of photography in your mind, making it personal in that you’re accountable to your own politic in the images you make. And it slows the process of production.

“Traditional processes can get discussed in relation to nostalgia, but I don’t relate to them in that way”

In The Social Photo, Nathan Jurgenson writes about photography now being seen more as a language than an art form: on social media you’re taking pictures just to send a message. Is that a problem?

Hito Steyerl wrote about the democratising of photography in her essay In Defense of the Poor Image. To oversimplify one of her points: when we’re not obsessed with high-quality images, and when everybody has their hands on this technology, a person can really see things through photographs in a new way.

We’re seeing now bystanders, and organisers using it to record police brutality, documenting the murder of unarmed Black civilians, bringing together masses of people in protest. If you trace that back to what the photograph of Emmett Till did, adding fuel to the fire inside of the civil rights movement, I think that positive uses of technology are many, and they have just grown from media-controlled newspaper images to civilian sharing via Twitter, Instagram, Facebook.

But ultimately, outside of those instances… so much of photographic technology gets utilised by the military, gets weaponised. I have very little optimism around technology and its uses of pixel-based images.

And the apps we use are owned by corporations who are so ready to sell your data…

At this time it’s complicated to talk about, because I’m somebody who doesn’t immediately need to access data that is going to be life-saving. Situate what I’m saying inside the knowledge of my own privilege around that, and the necessity and positive impact of that technology in the ways we already discussed.

But I have a friend at the ACLU who posted some bullshit statement that Amazon put out about their support of Black lives. The ACLU reposted it, saying, “Thanks a lot Amazon, why don’t you stop selling facial recognition software to the military?” I talk a lot about facial-recognition software as a sort of continuum of terrorism.

After I was in college, when laptops became more common, everybody taped over their webcam. This was before we knew about data mining, there was just this mistrust—anything you’re engaging in on your computer, someone’s watching and you don’t want them to be. Fast-forward fifteen years and everyone’s doing face app shit and all of that data is being mined and sold.

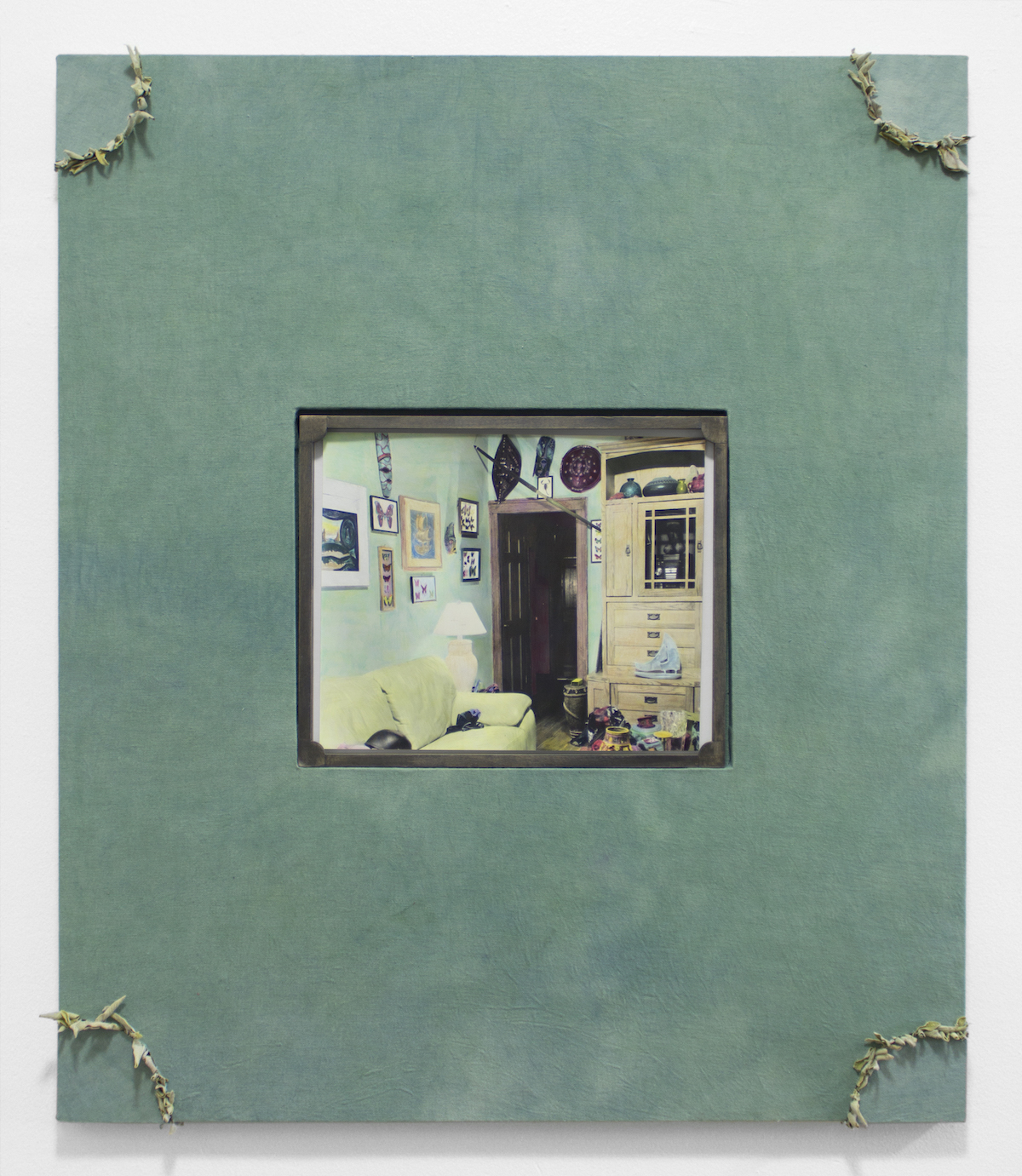

- Getting There (All Quill's are Reincarnated) For Sheilah and Dani ReStack: Part 1, 2019

“I have very little optimism around technology and its uses of pixel-based images”

I also think about how images can disguise material inequality.

That’s why I take the teaching of photography really seriously. I think photographic literacy is key to survival. To be able to decode those messages is hard to do.

I think about that relative to how I take and share photos; who I share them with and what the context of sharing is. For a long time I’ve been really fearful of co-optation. There’s this idea that, because of modernism and its entrails, we still expect the artist’s subjectivity to be irrelevant: you can just look at the work and get everything that you need from it. That still propels a lot of artists to withhold intention, meaning, or their personal life. I think that that’s not a great leftover from modernism—it doesn’t serve a very holy purpose.

But there’s another type of withholding that’s self-protective. There’s an Édouard Glissant text I read with my students called For Opacity. It’s not specifically about images, but how understanding is a type of imperialism, that there’s a right that people have to opacity. A lot of my work is tied very personally to who I am, my life and my deepest thoughts, and any moments of withholding are more to do with self-protection and not wanting to be fully understood, because I don’t know that everybody has the right to think that they could fully understand anybody.

- Free Field (Celeste, Bataille), 2018