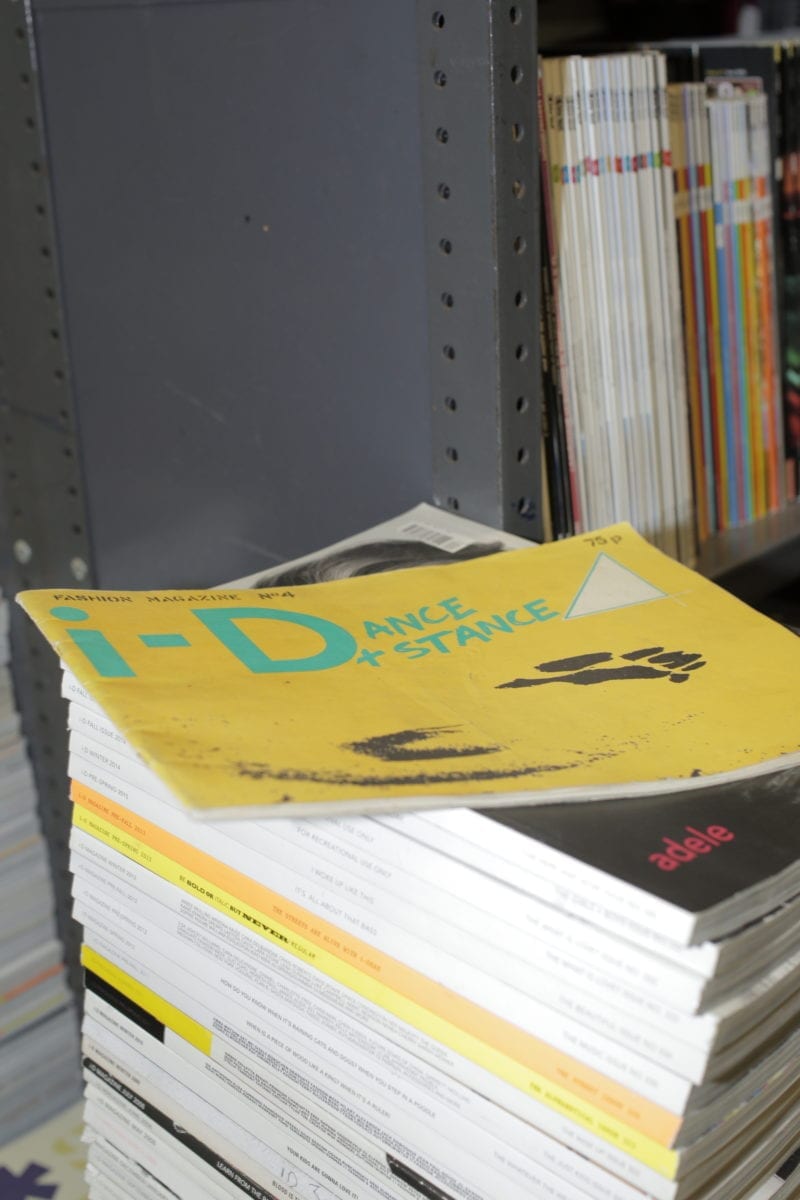

What does the world’s largest magazine collection look like? I’m lucky enough to know, thanks to one sweaty summer spent in a storage unit in North London eight years ago, when I assisted in the early stages of cataloguing Hymag, the now Guinness World Record-holding collection, with owner James Hyman and curator Tory Turk.

“15,000 kilos of magazines were delivered to the warehouse in Islington. All the boxes had plastic cords and we only had one pair of scissors; we never got more! We’d pop open a crate and literally anything could be in there,” Turk reminisces. I remember it well, and while it once seemed like the task of organizing thousands of titles in piles on the floor—from NME to Personal Computer World—was insurmountable, it has now been transformed into an organized library housed in a warehouse in Woolwich. A third addition to the team, Alexia Marmara, has a seemingly encyclopedic recall of where to find titles that are yet to be filed, as the archive continues to grow.

- © Louise Benson

“We call it heaven, the final resting place for magazines,” says Turk, who has seen the collection grow from 50,000 at the time of winning the record in 2012, to include around another 30,000 unsorted copies in 2015; at present the count exceeds 150,000 and is growing daily”. This is predominantly thanks to donations, where collecting obsessives (or their immediate family) have wanted to see their hard work saved and cared for. “We’ve had amazing donations, such as Athletics Weekly, given by a woman whose husband had passed away,” Turk adds. “He’d been collecting it since the forties and had every single issue. She wanted it to go somewhere where it had some sort of cultural value, and we’ve become the custodians.”

While a title like this might not spark immediate interest, Turk explains that this sort of history yields unexpected gems. “You might think this kind of magazine is quite boring, but there’s the first Nike advert, and the history of the Adidas running trainer, when it was just a sports shoe and not a fashion item.”

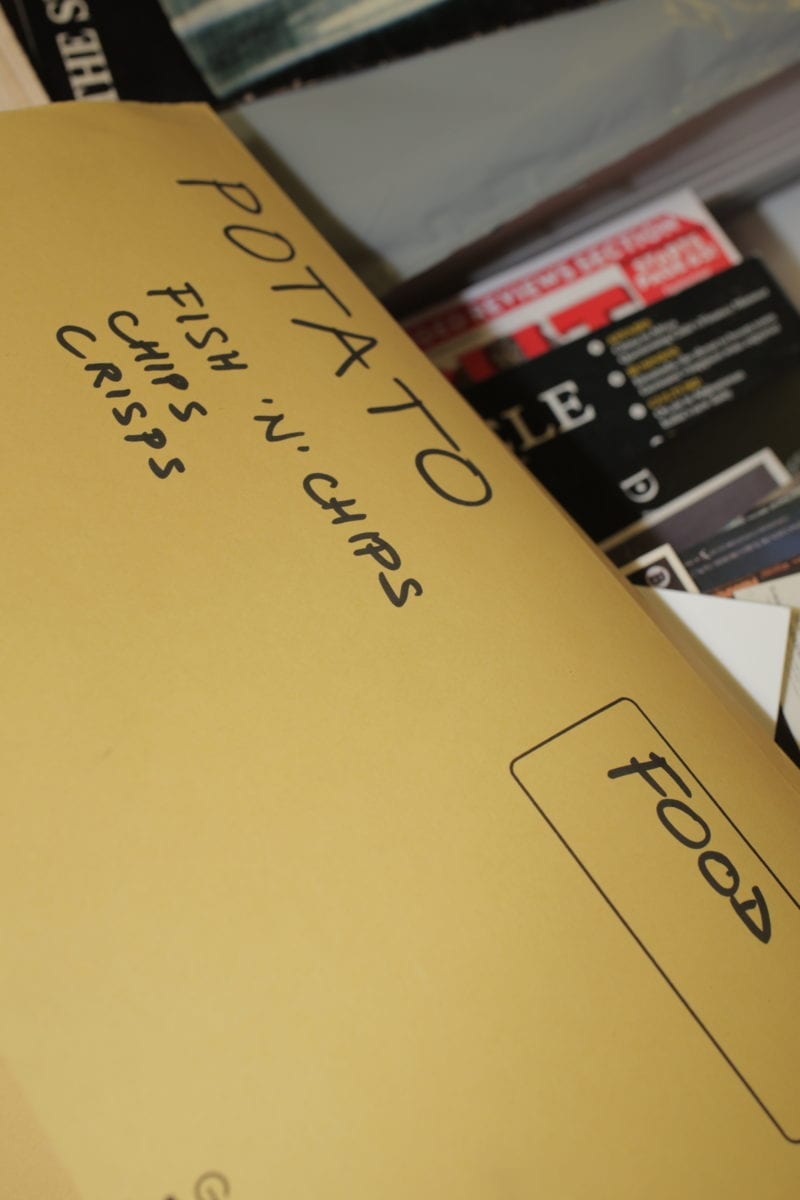

Other incredible donations include Edda Tasiemka’s collection. “She had a cuttings business in the sixties, seventies and eighties, where people would go to research,” Hyman explains. “Say you’re doing an article on elephants, celebrities, politicians—anything you wanted—and she’d have a file of cuttings from newspapers. She didn’t really evolve with the Internet, but she had millions of files and she gave it all to us. They are absolute gold. Recently someone got in touch because they’re doing a PhD on potatoes, and we have a file for that.”

- © Louise Benson

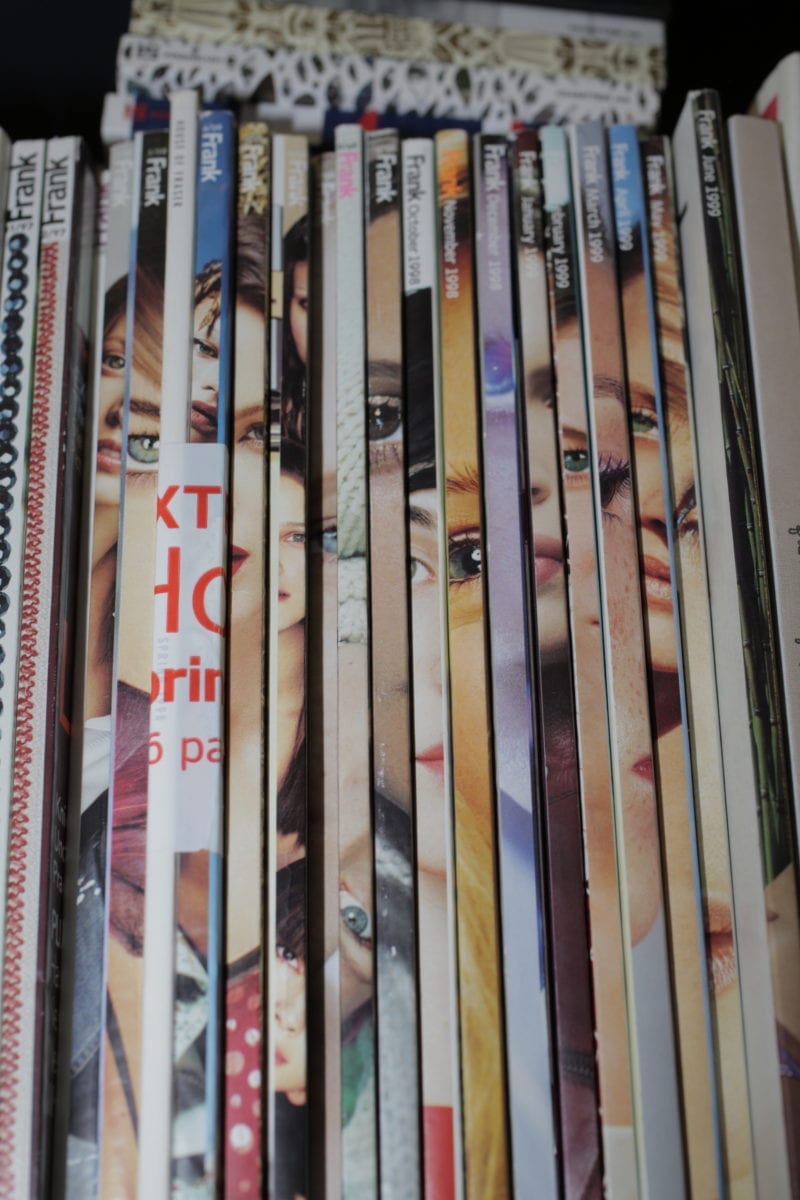

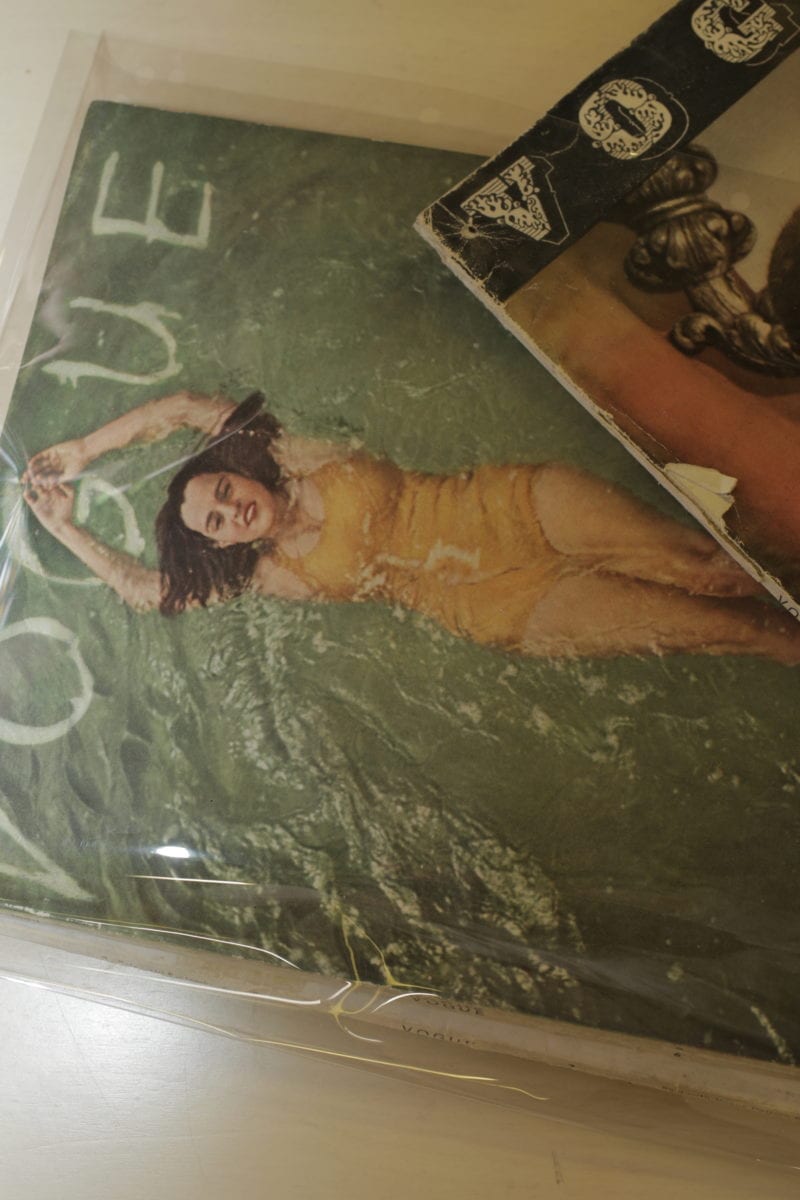

This resource is so large that it is housed on a separate floor, alongside a major fashion titles loan from writer Colin McDowell, encompassing the likes of vintage Vogue and Harper’s. For him, the collection was a personal reference library, which is the same reasoning Hyman applies to his voracious collecting habits. “It all started as research, back when I was scriptwriting at MTV and producing programmes—it was concurrent with everything I did. I loved reading magazines and I still do to this day.”

Simple research is a long way from this enormous collection though, and Hyman admits that he got pretty obsessive. “I’d worry if there was a slight tear or fold—I’m not like that anymore!” While the plethora of music and pop culture titles makes sense given Hyman’s line of work, other specialist magazines would probably have seemed like madness twenty years ago. Take, for example, Net, a print periodical about the Internet (I’m amazed to report that it’s still going). “On the spine it showed the growth of how many people were online,” says Hyman. “16.5 million in December 1994, and 39 million two years later.”

- © Louise Benson

That kind of data is incredible to see in such a strange, concrete format, and it’s these kind of leftfield information sources that the Hymag gang want to harness, and fill what has been termed the “twentieth-century black hole” that has rendered so many titles inaccessible due to copyright laws.

“We want people to get a royalty for every picture or piece of text that is read”

Which brings us to the next big project: digitization. Turk elaborates, “We’ve been researching what we can actually do with this data through digitization. If we want to digitize something, we need to do due diligence and work with the industries. James and I have been doing that for four years.” Hyman adds, “We’ve been meeting photographers, authors, illustrators and publishers, to be transparent and do everything legally, as opposed to running into any problems down the line.”

The aim is to build a subscription model where a portion of the revenue goes to rights holders, just like music. According to Hyman, “We want people to get a royalty for every picture or piece of text that is read. That’s not happened very much because this has long been a grey area. A lot of this content was built before the digital boom, so no-one had even thought about any of this.”

At present, Hymag has announced a partnership with The Face (digitizing every cover and page from 1980 to 2004) and has developed a pretty comprehensive prototype that shows just how much information can be extracted from the collection. With a mere thousand sample pages the team demonstrated the exacting data capture (thanks to digital facial and text recognition technology) by pulling a photoshoot with David Bowie featuring the word “Berlin”, as well as a string of adverts, editorial shoots and covers featuring Kate Moss, which in turn were shown in graph form, giving a pretty accurate read on the fashion trends of the last two decades. For Hyman, the objective is clear: “We want to go beyond simply providing a magazine article and give you the analytics.”

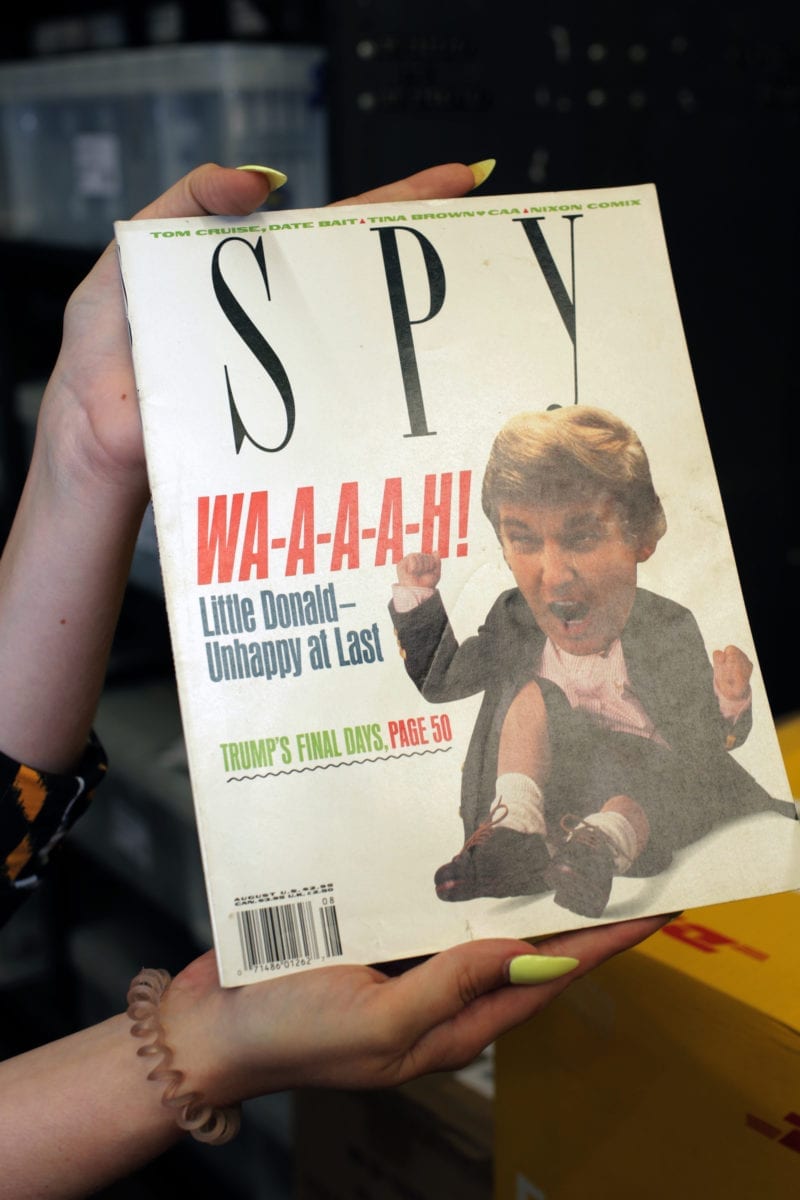

The possibilities unlocked by this bounty of information is pretty mind-blowing, particularly because, as well as pulling concise data, the physicality of the magazines is maintained. Though the act of tangibly holding an old copy of Smash Hits or Spy can’t be replicated, the layouts, typesetting and cover lines—not to mention gossipy fifty-word segments and banal everyday listings—all remain intact.

“These magazines are all made with blood sweat and tears”

What is flattened by viewing these pages through a screen is reinvigorated by the fact that all of this pre-Internet content has been rescued and preserved, and there’s no denying that the tone of much of the journalism is “More honest. More real,” as Hyman terms it, “there’s more sincerity in having a three-page feature in NME than something slapped up on Twitter with a quick, artificially staged picture.”

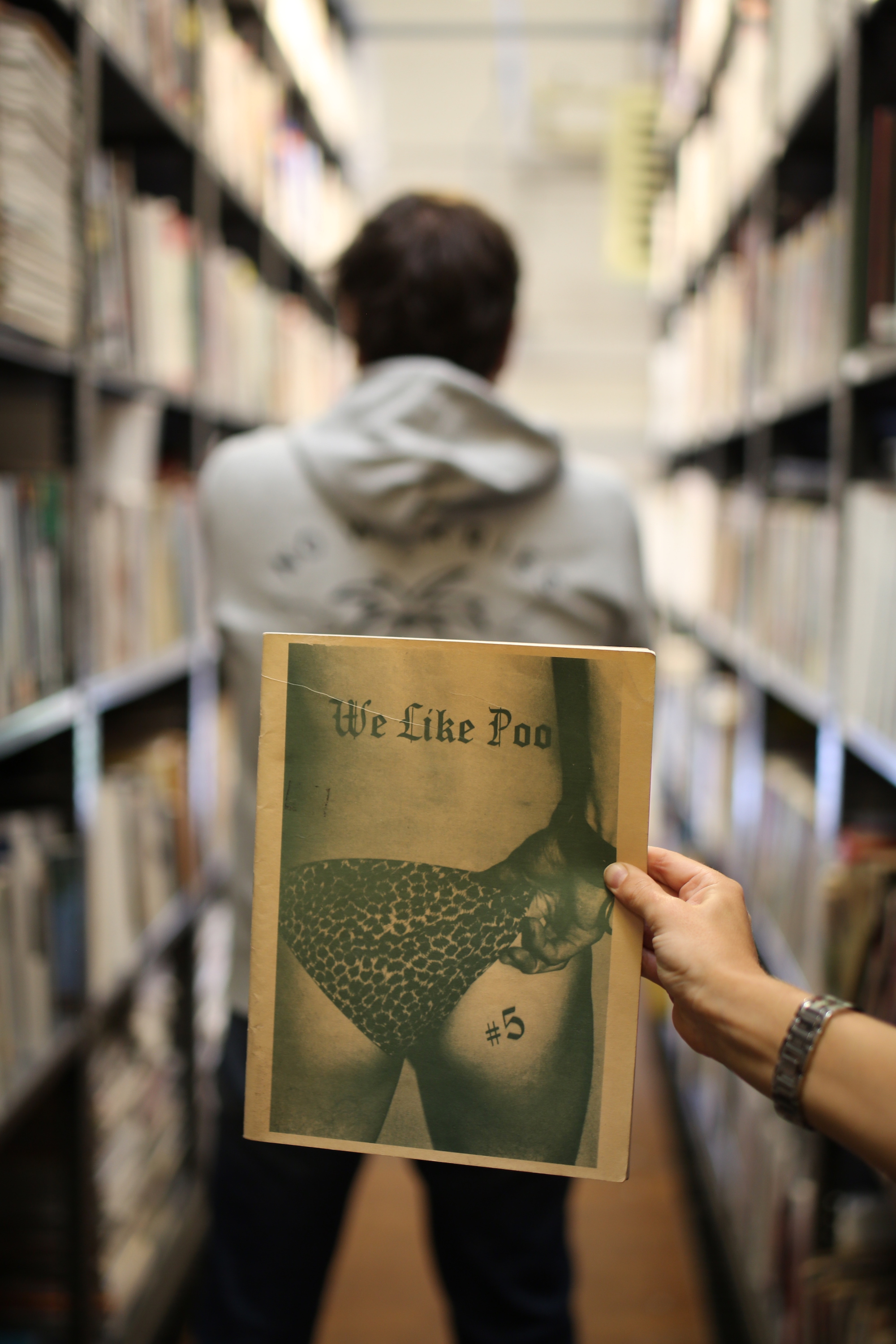

It’s hard for nostalgia not to take hold, particularly when the team reveal a vast array of niche titles adorably catalogued as “heartfelt zine”. These independent, self-funded magazines are nothing short of joyous, and are dangerously close to being lost in the sands of time. Take, for example, Fact Sheet Five, a zine about zines covering everything from UFO’s to the Riot Grrrl movement. It’s like a Yellow Pages, with each entry carefully crafted by the long-suffering editor. Another example is We Like Poo, covering poems and anecdotes, which shuttered due to too many unsolicited faeces packages.

“These magazines are all made with blood sweat and tears,” says Hyman. “The editor’s letters are so incredible: ‘My wife is pregnant; I got shot; I’m bankrupt; but I just had to get this out to you.’ They were real labours of love.” As we all get misty eyed (particularly Marmara, whose own experience growing up in the digital age means she yearns for the physical) I’m reminded that Hymag is on the move and will be largely inaccessible while digitization projects take place. My heart sinks slightly, as I remember sitting among thousands of old (newspaper) copies of Rolling Stone or leafing through hey-day Playboy issues, but I take comfort in the fact that, if all goes well, this incredible resource will no longer be limited to a privileged few.