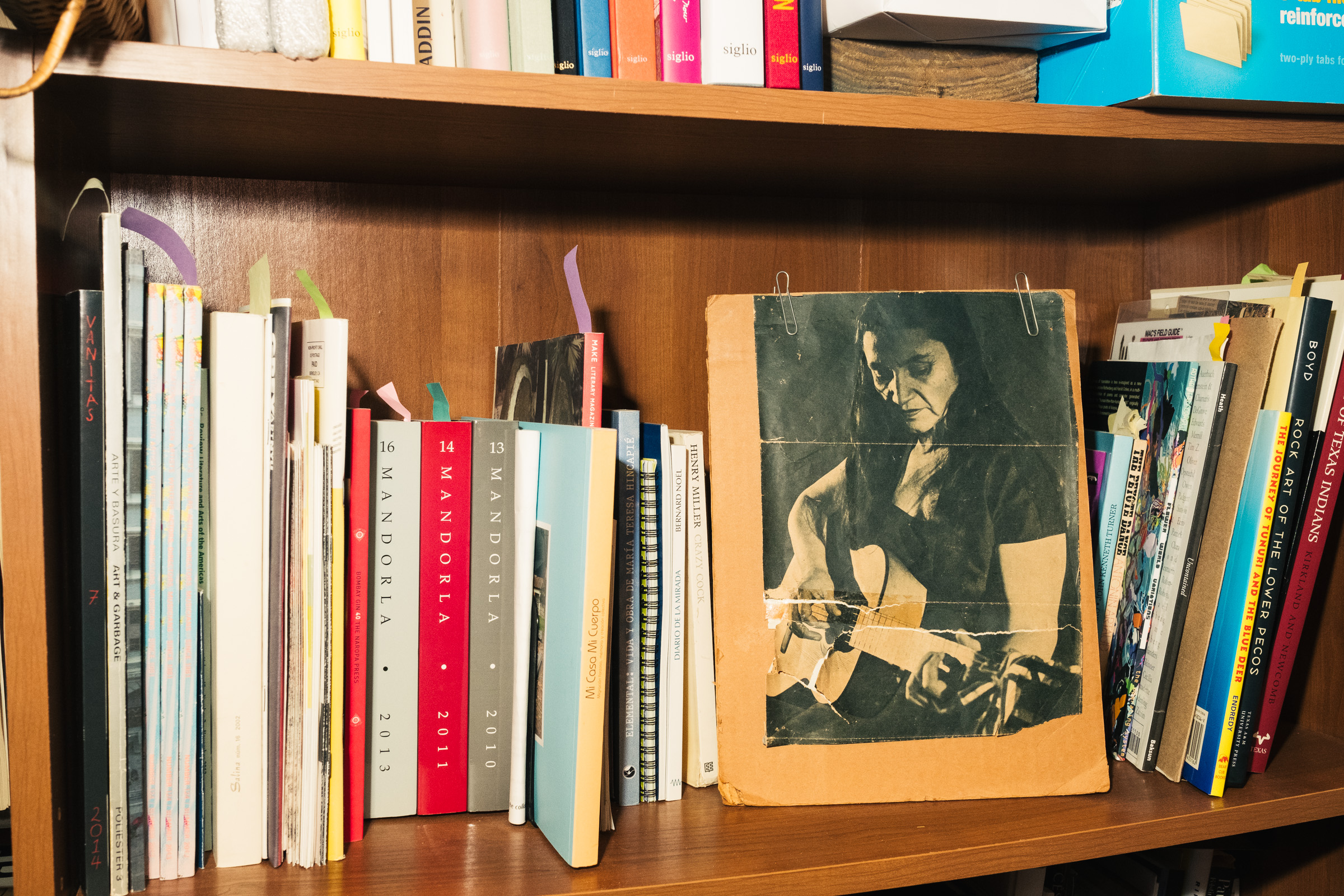

Arriving at Cecilia Vicuña’s TriBeCa apartment-cum-studio, I am ushered in through a dramatic drapery of plastic that partially obscures numerous floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, as if I’m entering some secret hideaway. The artist assures me that the plastic is temporary; just the result of some old building facets that needed a facelift. The books, however, prove to be the bones of the seventy-year-old artist’s home, if not her artistic life on the whole.

Arriving at Cecilia Vicuña’s TriBeCa apartment-cum-studio, I am ushered in through a dramatic drapery of plastic that partially obscures numerous floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, as if I’m entering some secret hideaway. The artist assures me that the plastic is temporary; just the result of some old building facets that needed a facelift. The books, however, prove to be the bones of the seventy-year-old artist’s home, if not her artistic life on the whole.

Vicuña is a noted poet and author in addition to an activist and artist. She’s been in exile from her home country of Chile since the early 1980s, when a military coup resulted in a violent dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet that finally ended in 1990. Her work, both verbal and visual, rests heavily on the importance of reclaiming ancestral traditions as a tool of resistance, exemplified by raw wool installations and sculptures known as Quipu, which reference the ancient Andean system of recording statistics and stories through a complex knotting of coloured thread. She also explores the power of intuition and activism in the face of oppression, patriarchy, white supremacy, totalitarian rule and ecological devastation.

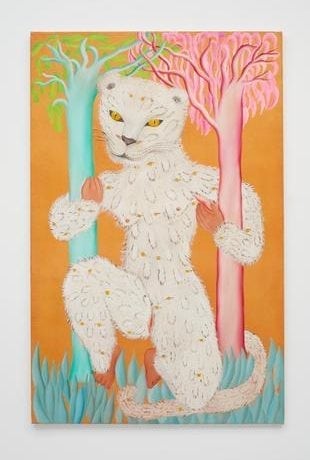

While her work may seem incredibly of the moment as social awareness of global warming and systematic abuses of power continue to grow, Vicuña’s career stretches back fifty years, though largely under the mainstream art world’s radar. In fact, despite living and working in New York since the 1970s, her current show at Lehmann Maupin gallery is only her fourth in the city, and it represents the broadest survey of her work yet.

Your exhibition at Lehmann Maupin is your most comprehensive show in New York to date, even though you’ve been working here for decades, right?

I’ve been in New York for forty years and in that time, I think I’ve had three exhibitions here. The first big show was at an alternative space called Exit Art gallery in 1990, but because I was virtually unknown—I’d only ever really shown around Latin America—hardly anyone came. In 1998 or ’99, I had an exhibition at Art in General, which got a little more attention. But it was only really one of my works called Cloud-Net, comprised of big ropes made out of alpaca wool that crisscrossed the space. It was a piece about climate change, but no one that wrote about it addressed the issue of global warming. They just interpreted it as work of monumental weaving. Not a single person understood what the actual subject was. My third show was at the Drawing Center in 2002, which was again fully and completely ignored.

“Everything is dying, we’re killing our own means of survival”

The issues of environmentalism, feminism and global inclusivity that your work raises seems so timely now. Why do you think critics and dealers were ignoring your work twenty years ago? Has the public simply not been ready to confront some of the problems you address?

You could say it’s a confluence of many reasons. That would be the principal one, because look at what’s happening now with the planet! Denial is still our main attitude toward it. Everything is dying, we’re killing our own means of survival and yet most of us can’t see how little political action is taking place compared to what needs to be. There have been so many efforts on my part and others to get this information out, but maybe people don’t know what to do with it.

Another big reason, at least in my opinion, is that there is very little appreciation for indigenous cultures in the US. I am an indigenous mestiza and that means you’re like a non-person here, what you do is kind of irrelevant. For example, Lucy Lippard wrote once that I was working in the landscape before the Land Art movement began, but she was the only art historian that ever noticed that.

When white artists like Carl Andre and Walter de Maria started making Earthworks in similar ways and were billed as innovators by the history books, I’m sure you were justifiably miffed.

On the one hand, I benefited from being overlooked because it allowed me to be free and to experiment because I had no fear of ever being seen. I feel like this is the story of practically every woman creator for the last five thousand years. How many extraordinary women had the very fact of their being silenced in art, philosophy, science—in every field? So, I felt in good company. But it felt sad at the same time because all this work I was doing was going to die with me.

Do you feel that your work is finally getting some qualitative attention, especially on the heels of your acclaimed show About to Happen at Contemporary Art Center New Orleans last year, and this current exhibition at Lehmann Maupin?

You know, when I was installing at the gallery the other day, suddenly there was a moment of quiet and I became overwhelmed emotion because I felt like my existence had finally been acknowledged. That has been an unknown feeling for me. From the moment I was born I knew that I wasn’t wanted because I wasn’t a boy—my family expected a boy because I was the firstborn. I was living disappointment, and that’s how a lot of young girls grow up in Chile, knowing they’re considered lesser beings. It’s a very profound and brutal reality. Women make the best of it, they either become complicit in it, or they accommodate it. But I was always aware; I never gave up my sense of awareness.

This idea of “awareness” seems to underpin a lot of your work, don’t you think? You thread together existential aspects that range from issues specific to you, such as being a woman of color working in a male-dominated world, to macro issues of political corruption and even rapid environmental change. In fact, it seems like all of these things, no matter the scale of them, are woven together for you.

I think that comes from my upbringing. I was very fortunate to be born into a family of thinkers and philosophers and historians and scientists. Most of the women were artists—two of my aunts were, and both of my grandmothers to an extent. One of them was married to a wonderful man, my grandfather, who was a historian and a civil rights fighter. So I had a very strong political education as well, although he was in and out of jail for that reason; it fell to my grandmother to raise and educate all of the children. I grew up watching women who not only cultivated a kitchen, a garden, and a library, but also a studio. It was natural to thread all of these aspects together—caring for people, studying, and drawing. My mother says that even before I was speaking I was already drawing. I remember when my grandmother noticed that I was an artist and she said to me, “my darling, don’t ever get married.”

Did you ever get married?

Yes, I did [laughs].

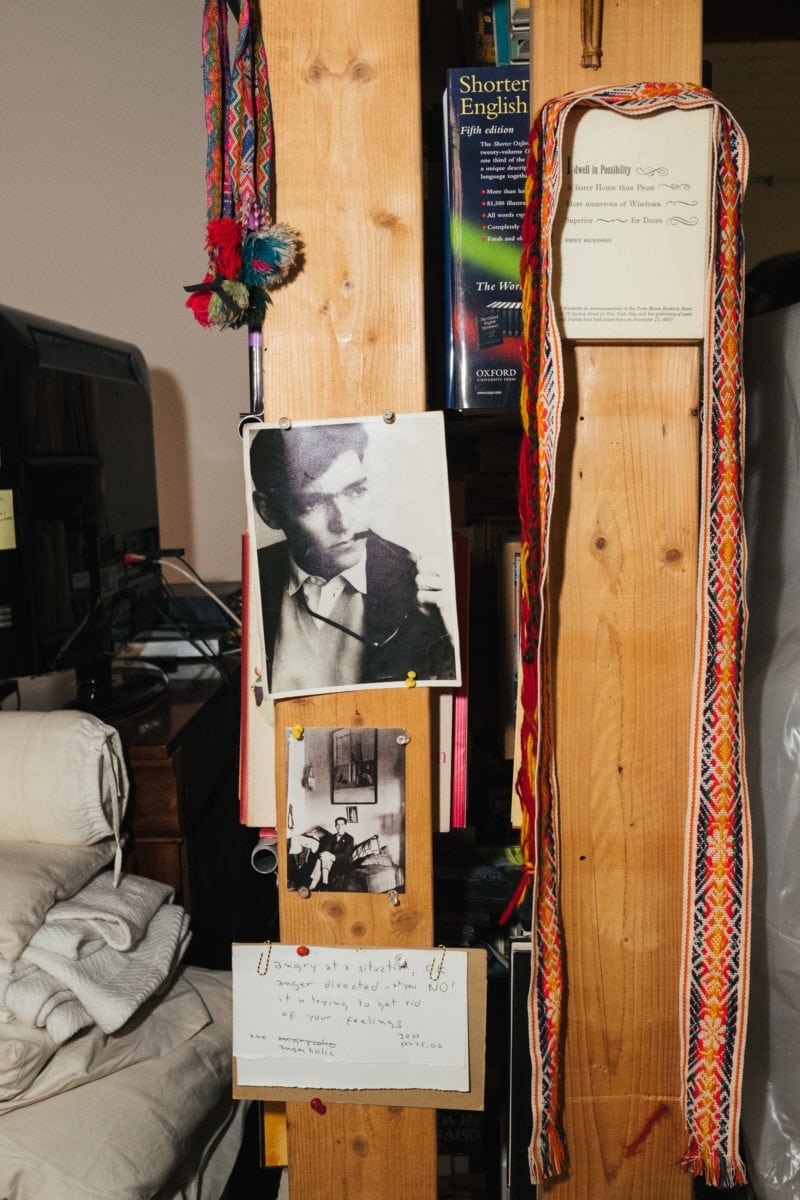

Speaking of libraries, you have a significant one of your own here in your studio. Have you read all of these books over the years? Does what you read shape your work?

When I divorced, I had sixty boxes of books packed up and delivered to me, though my husband claimed they were his. I have had a lot of books given to me, but I buy so many as well. Reading is a passion, as is writing. I read a lot of philosophy, science and poetry, as well as a lot of works related to ethnology. Reading and learning are like breathing for me; I must do it.

“There’s an awakening going on right now that has become very powerful. You can tell that the power of women is growing”

What is one of the most valuable things you think you’ve learned?

That women are masters of self-hatred. Our culture teaches us that, not books. We’re taught that any sort of imperfection is a failure. Nothing will come from that negative mode of being; we must teach ourselves to move past that—and we can. One of the strong points of being a woman is our survival instinct. It’s so powerful, and part of that instinct is to embrace joy and wild pleasure. You know, there were whole towns in southern Chile that were tortured by soldiers under the Pinochet dictatorship. The women were not only tortured alongside the men, but also raped. Thirty years later, you look at these groups of people, and the men have been demolished. The women, however, are free, happy. You ask them why? How did they transform all of that humiliation into happiness? They say, “we talked.” Through communication, they can share the burden of their pain, in order to rebuild.

Blending as it does tradition, language, poetry, craft and nature, do you think your work functions as a form of communication, too?

I think so because you know what? Lately, women have come for my work. They understand it, it speaks to them. That’s why you’re here right now—you are a woman. There’s an awakening going on right now that has become very powerful. You can tell that the power of women is growing because the abuse and violence against them have also increased and become more visible. But if we can communicate with each other, we can survive the abuse and hopefully end it for good.