Ah, Edinburgh in August. There is genuinely nowhere else like it. For a month, it feels like the Scottish capital

is the centre of the world. Trump, Brexit, Russia, your relationships, your mortgage, your kids—none of that matters. All that matters is your next show, your next coffee, your next review, your next pint. For a brief period, the city is the bubbliest of cultural bubbles.

It’s actually not just one festival, it’s several—the Edinburgh International Festival (EIF), the Edinburgh Art Festival, the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo, the Edinburgh International Book Festival and, of course, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. They all jostle for space, clambering over each other and coexisting happily amid the cobbled streets and coffee shops.

The Edinburgh International Festival is the discerning dad of the bunch, the elder statesman. Its lineup this year is eclectic—Alan Cumming, Wayne McGregor, Django Django, and John Grant are just some of the names that appear in the programme, alongside the usual roster of classical concerts—but it’s also a bit underwhelming, the opening event aside. Anna Meredith and 59 Productions’ Five Telegrams is a vast, abstract animation screened onto Usher Hall in time to a contemporary classical score from Meredith.

The performing arts lineup is dominated by Paris’s Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, which was revitalized by Peter Brook in the mid-seventies and is now a Mecca for European avant-garde directors. It’s this year’s company in residence at EIF, presenting three shows over the month, the most eye-catching of which is La Maladie de la Mort, the fourth collaboration between auteur Katie Mitchell and writer Alice Birch.

The show—an hour-long adaptation of Marguerite Duras’s 1982 novella—is a visual, technical marvel. It reframes Duras’s story about an anonymous man searching for a connection with an anonymous prostitute, as a live film shoot. Laetitia Dosch’s woman and Nick Fletcher’s man are performers playing parts, darting around Alex Eales’s open-fronted hotel room set to act out the story, while a phalanx of cameramen and boom-holders scurry around them. The resulting video feed is screened live above the stage in black and white, with Irène Jacob’s French narration subtitled throughout.

Live video feeds have emerged as a staple device for a certain class of international theatre director in recent years, championed by the likes of Ivo van Hove and Robert Icke. Mostly, video has been used to supplement the action; rarely has the emphasis of a show been as firmly focussed on the footage as it is here. The result is that the emotional core of Duras’s story, and the elegant feminist reworking given to it by Birch, is sidelined. Perhaps that’s the point—Mitchell is certainly playing around with the concept of alienation and gaze to a degree—but it nevertheless renders La Maladie de la Mort an intelligent but ultimately emotionless adaptation, indicative of an EIF programme that hasn’t quite hit its mark this year.

Where the EIF fails to fulfil, though, the Fringe is always there to pick up the pieces. The sheer volume of shows on offer—over 50,000 performances of 3,548 shows this year—means that there’s always something interesting to look at. The Traverse Theatre always dominates the early days of August with its roster of polished, professional productions, the most talked about of which is David Ireland’s controversial comedy Ulster American, but the most visually stimulating of which is David Leddy’s Coriolanus Vanishes.

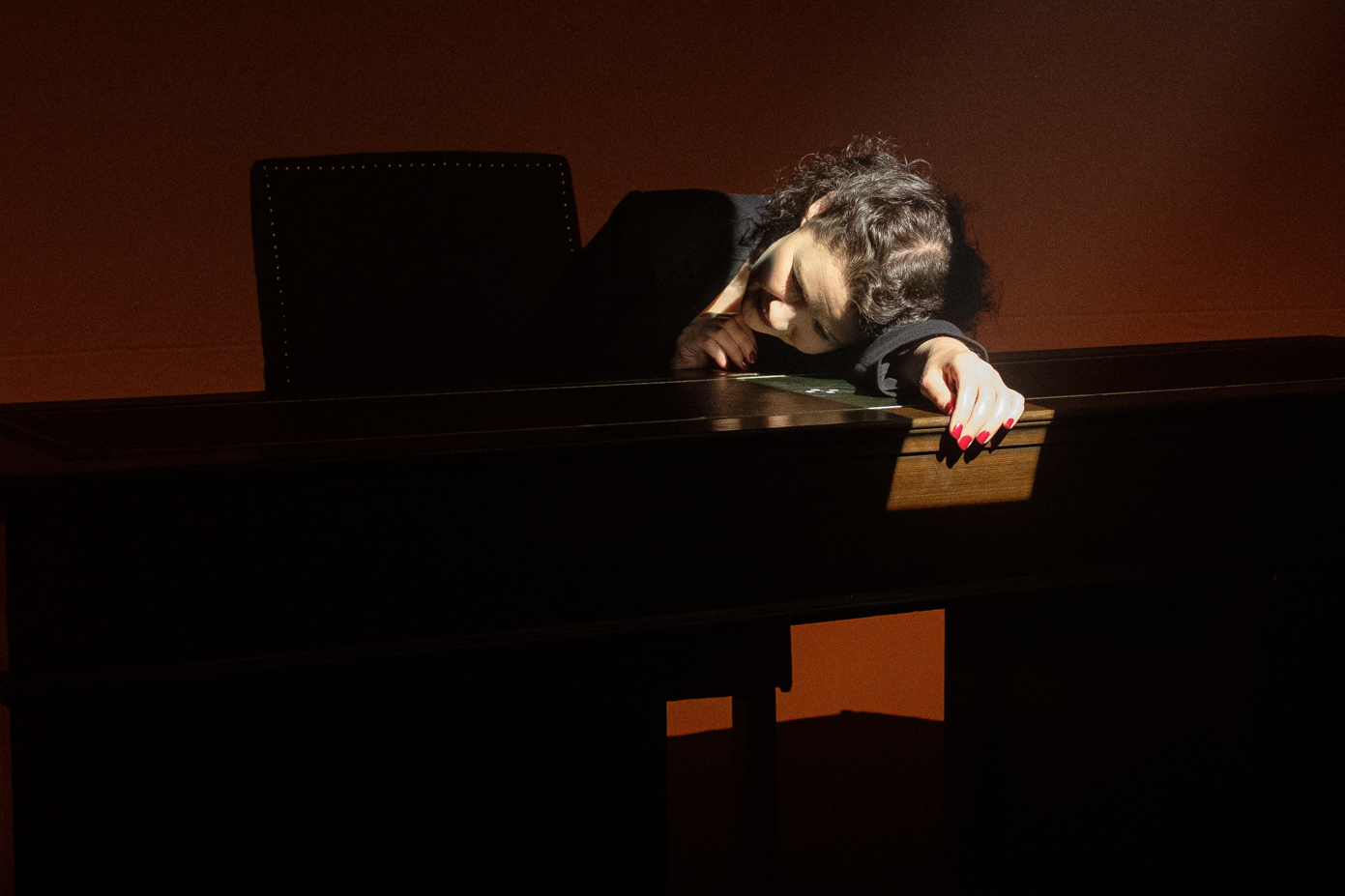

An hour-long monologue, Leddy’s play is written for any gender, but is here given a gripping, gut-twisting performance by Irene Allan. The work itself is a detached and devastatingly raw monologue about an individual struggling with anger and anxiety, but its Becky Minto’s stunning design, augmented by Nich Smith’s lighting, that makes Coriolanus Vanishes so starkly memorable.

“There have been few more impactful or apposite designs in Edinburgh this year”

Allan performs on a slightly elevated platform, sat at a desk and entirely surrounded by blackness. As the monologue progresses, each chunk is illuminated by lancing red lasers, neon strips of white light, or deeply coloured backdrops that pulse and throb with energy—flashes of vivid colour in the darkness. There’s one astonishing moment when Allan stands on her desk, umbrella in hand, and a shower of golden flakes falls upon her, glinting in a shaft of golden light. It’s a harsh, haunting but beautiful setting for a harsh, haunting but beautiful play. There have been few more impactful or apposite designs in Edinburgh this year. Scratch that, there have been few more impactful or apposite designs in Britain this year.

After the first few days of the festival, the focus shifts across town. Summerhall, Edinburgh’s repurposed veterinary school just off the Meadows, has been the hipster hangout of choice in recent years. Plenty of shows at the Fringe are produced on a tight budget, so visual design often suffers—few companies have the resources of the Traverse behind them. Not so with A Fortunate Man, Michael Pinchbeck’s thoughtful adaptation of John Berger and Jean Mohr’s 1967 book of the same name.

Berger and Mohr’s work laid out text and image hand-in-hand to explore the life of John Sassall, a country doctor working in the Forest of Dean. Pinchbeck’s two-handed theatrical version marries the textual and the visual well on stage, too, supplementing an intelligently filleted portrait of Sassall with a series of arresting, abstract metaphors—leaves scattered on the ground, bandages wrapped around trees, shredded paper littering the floor. A Fortunate Man emerges as a tender, multi-layered collage of one man’s tortured life, and a testament to what Fringe productions can do on limited resources.

With all the vitality and vibrancy of the Fringe, the Edinburgh Art Festival can often feel like an afterthought. It doesn’t have hungover students flyering for it on the Royal Mile, it doesn’t have posters plastered to any and every spare space of public architecture. It doesn’t have flocks of Londoners getting drunk on craft cider and munching gourmet at its pop-up bars and bistros. It’s not “where it’s at”—surely something for the city to ponder over the coming years.

Much of the programme is actually made up of partner exhibitions at Edinburgh’s big-hitting galleries—you sort of get the impression that these shows would have been happening anyway, and that the art festival has just been allowed to collate them in a booklet. There’s a full-scale retrospective of Emil Nolde at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. There’s the largest ever exhibition of Canaletto paintings at The Queen’s Gallery. And there’s the first major exhibition of Scottish surrealist Edwin G Lucas at the City Art Centre. All three run for months after the festival finishes—they don’t, in truth, have that much to do with each other.

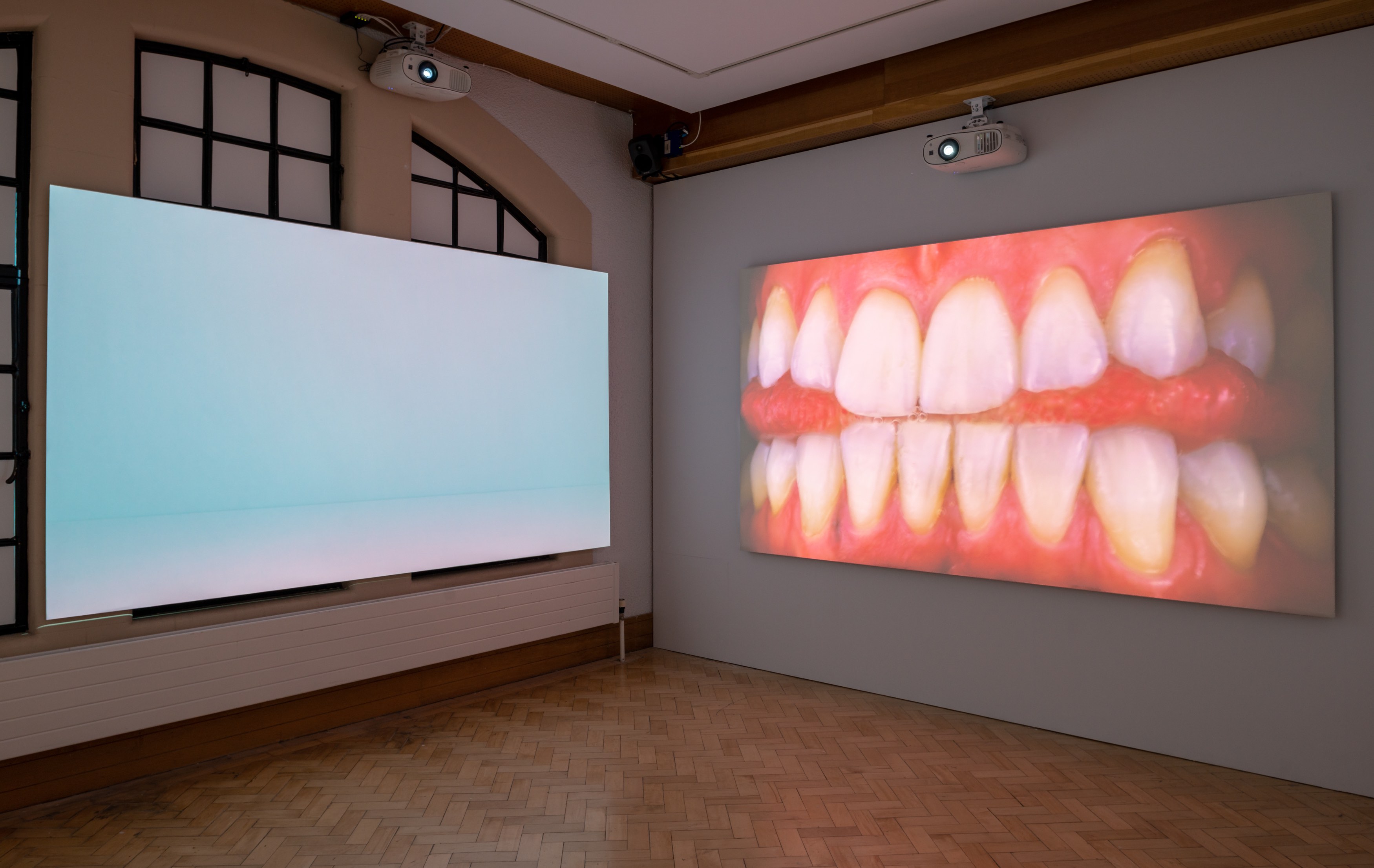

But its subdued, somewhat sidelined character aside, the art festival itself actually does have a few gems to offer, if one can be bothered to seek out a programme and make the trek to its scattered venues. The freshest fare is to be found at the City Art Centre, where Platform, the art festival’s annual showcase of early-career artists, is exhibited. Of the four practitioners selected by curators Jonathan Owen and Hanna Tuulikki this year, the most compelling work comes from Isobel Lutz-Smith, a recent graduate from the Glasgow School of Art working largely with video installations.

“Venues, trends and styles rise and fall over successive years up here—theatres, galleries and festivals fall in and out of favour”

Her contribution to Platform 2018, Sausageworks, is a head-spinning, four-walled room of squeamishly shot, hyperreal footage—potatoes, peas and meat being ground up, pushed along pipes, squished and squashed into shape; a nicely nauseating meditation on processed reality.

Venues, trends and styles rise and fall over successive years up here—theatres, galleries and festivals fall in and out of favour. New voices emerge. Old ones disappear. If the EIF has had a mediocre 2018, the Traverse has had a solidly strong one. Summerhall remains at the centre of the theatrical lens, while the art festival continues to struggle for a spotlight.

Commentators often try to come up with a theme when they write about everything that is happening in the city. This year’s theme is death, or this year’s theme is health, they proclaim assuredly. It is, frankly, bullshit. There is no theme. There can’t be with this much going on. Edinburgh in August is Edinburgh in August. Different ideas and inspirations abound, some comparable, some wildly divergent. That’s the beauty of it. There’s nowhere else like it.