Oil paint is the master’s medium. It offers boundless possibilities in terms of colour, tone and transparency, and is synonymous with the romance of creative impulse, from Caravaggio’s straight-to-canvas chiaroscuro to the inches-thick impasto favoured by Lucian Freud.

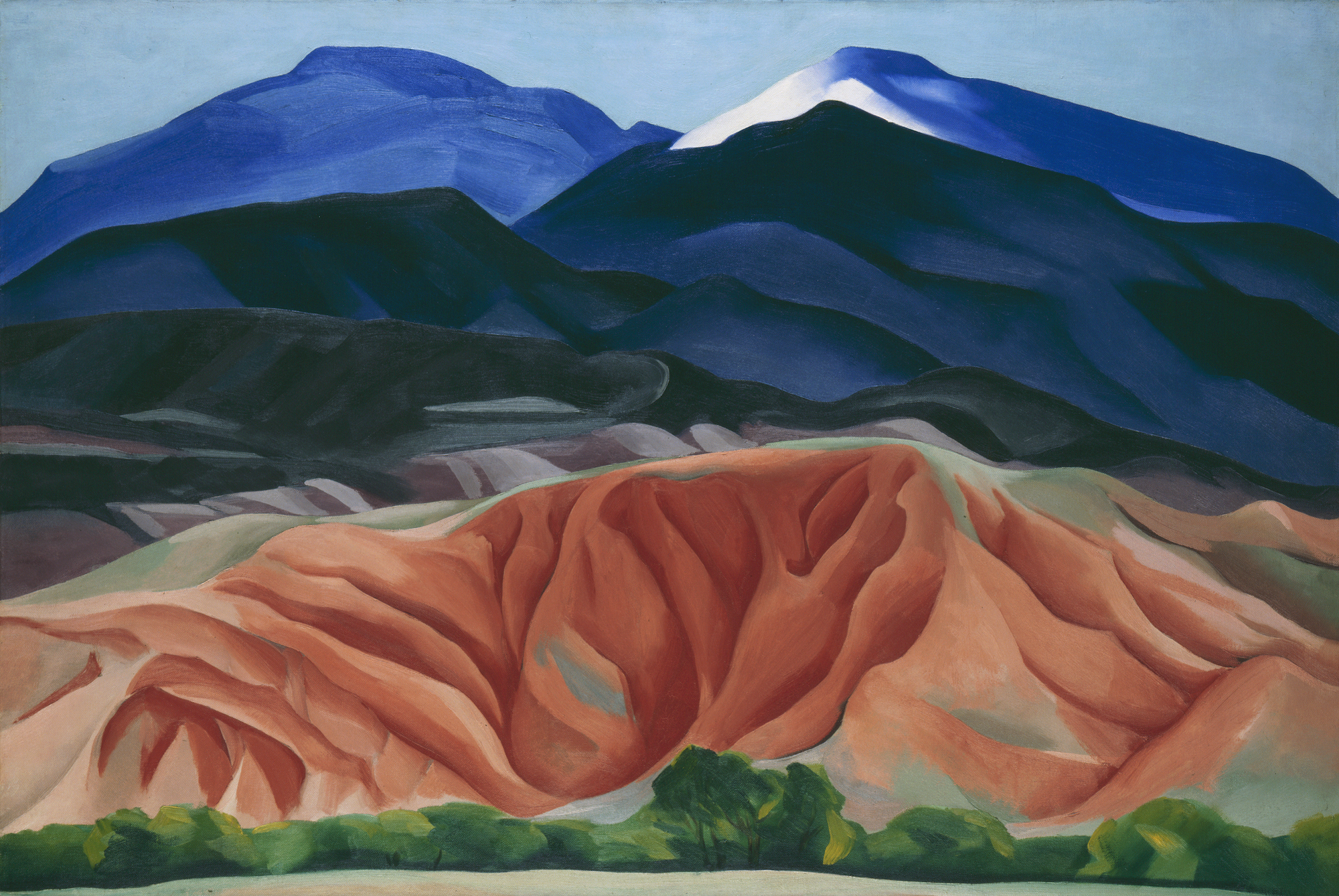

However, the bombastic spontaneity embraced by so many was complete anathema to Georgia O’Keeffe. While others might pull and scrape, carving up their canvas as they go, the trailblazing American modernist worked with meticulous precision, particularly when it came to her palette.

“She was the ultimate intentional artist,” says Ariel Plotek, curator of fine art at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. “It was apparent in everything she did, but we see it most in her command of colour.” Rather than working directly on canvas, she produced hundreds of paint-out cards, which allowed her to experiment with the opacity, shade and tint of each pigment ahead of time, as well as record their drying and curing.

“While others might pull and scrape, carving up their canvas as they go, the trailblazing American modernist worked with meticulous precision”

“Knowing exactly how her materials were going to behave freed her in terms of subject matter and composition,” says the museum’s head of conservation, Dale Kronkright. “She also relied on a core group of colours for most of her career, because she wanted to know exactly how they would behave.” Such shades included cerulean and cobalt blues in her New Mexican skies, iron-based reds and browns, as well as viridian green, known for its depth and luminosity.

O’Keeffe’s exacting standards meant that buying from reliable manufacturers was crucial. “She wanted constant characteristics, such as tint, power, drying rates and even the consistency with which it comes out of the tube,” Kronkright explains. As such, British brands such as Winsor & Newton became a mainstay, particularly after the outset of World War Two, when supplies from France and Belgium were largely inaccessible.

“She painted in a single thin layer, exposing the texture of her canvas and inviting the viewer to engage with the delicate qualities of her oils”

Like many of her contemporaries, O’Keeffe’s concerns over her materials were conceptual as well as practical. She painted in a single thin layer, exposing the texture of her canvas and inviting the viewer to engage with the subtle, delicate qualities of her oils. According to Kronkright, “O’Keeffe spent a great deal of time perfecting opacity and colour, and she wanted her audience to see those intentions. The last thing she wanted was the flattening and saturating effects of varnish on top of that.”

Unfortunately, the wider art world had not necessarily adapted to these new, modern concerns, as O’Keeffe discovered while hanging her show at MoMA in 1946. On encountering four loaned paintings which had been “cleaned and varnished” by their owner, the artist was so distraught that she demanded they be cut from their stretchers and burned—luckily, the museum conservator came to the rescue.

Holly Black is Elephant’s managing editor

Georgia O’Keeffe at Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Winsor & Newton supports the retrospective, 20 April–8 August

VISIT WEBSITE