According to numerous popular dream encyclopaedia websites, if a vision of a window comes to you in the night you might be feeling excited about new opportunities, or afraid to take them; you may be feeling a sense of freedom, or maybe you’re claustrophobic. In any case, a window represents a boundary between two things—specifically a point where that boundary becomes porous, but does not break down. A window is a moment when the boundary also becomes a frame; it highlights exactly where you cannot be. And now that many of us are suddenly spending nearly all our time indoors, those glassy panes point this out even more poignantly.

Windows have long haunted the western art canon. During the renaissance Alberti described the painting as an open window. The nineteenth century saw a proliferation of romantic painted visions of sunlight flooding through them, often ornamented by women with backs coyly turned, presumably longing for whatever was out there. “Everything from a distance becomes poetry,” wrote Caspar David Friedrich. It was easy to romanticise the pastoral scenes or streets below from the safety of a drawing room. These paintings simultaneously depicted what was longed for and what was already owned; naturally, the private home that was on the subject’s side of the window was cloistered in its privilege.

“A window is a moment when the boundary also becomes a frame; it highlights exactly where you cannot be”

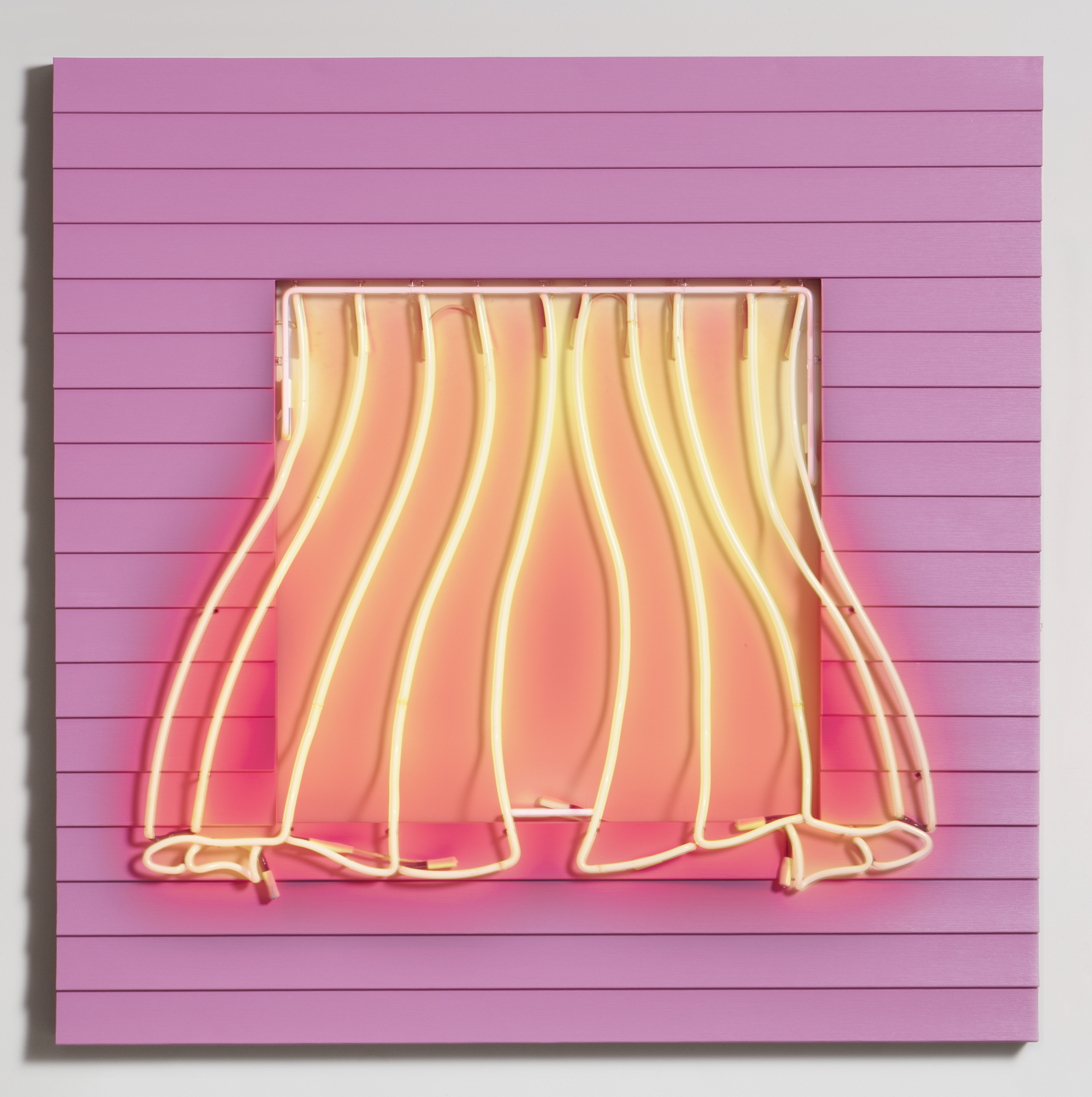

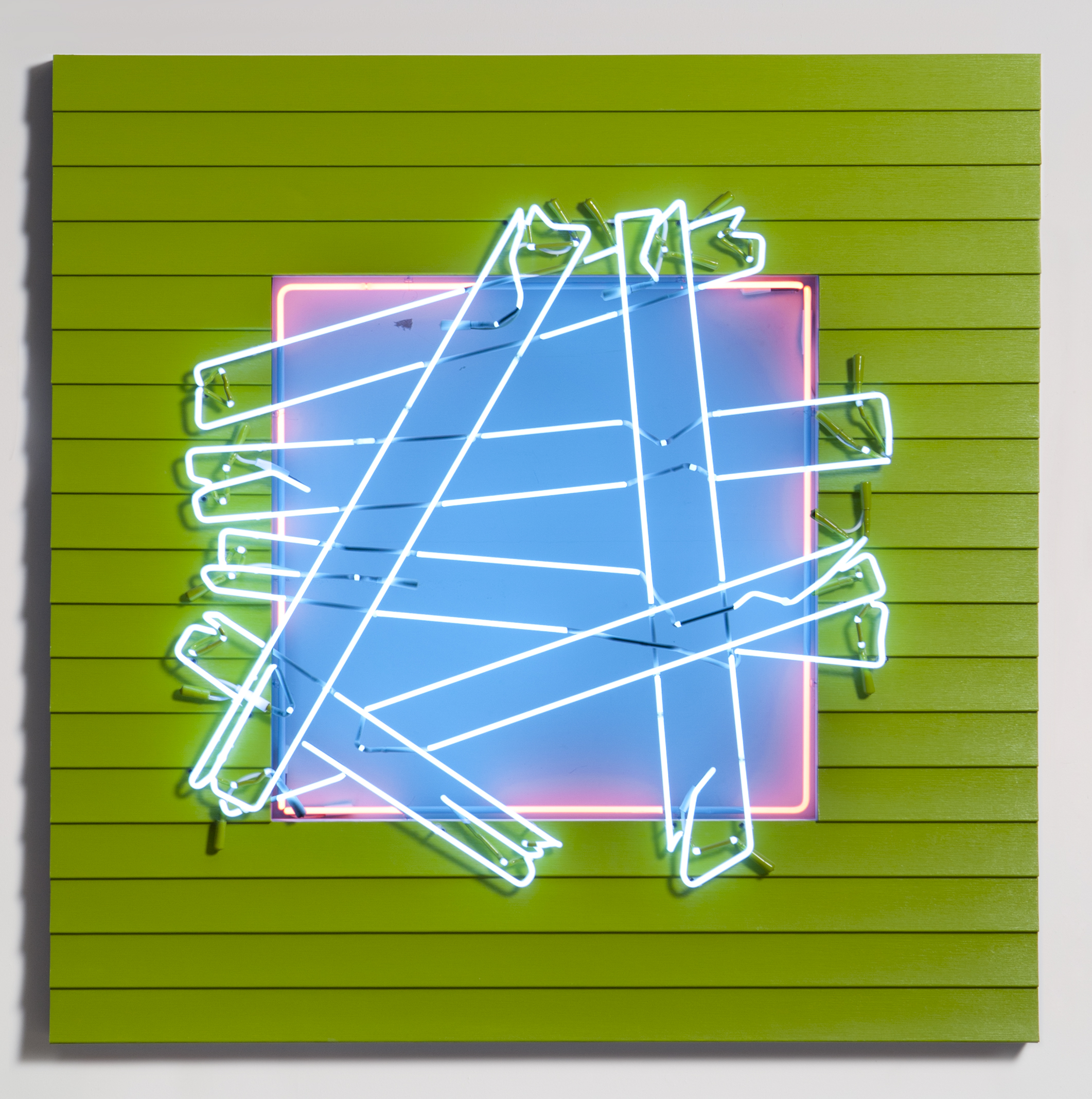

Fast forward to the mid twentieth century and the dominant image of the ideal home in American popular culture is one of sanctuary, intended for the “right” kind of family. A window into the home was thought of as a window into an idyll where every family member is peacefully playing their designated role. In his 2018 Bad Window works, American artist Alex Da Corte takes the windows of a mid-century suburban family home into Halloween, rendering them in flouros and adorning them with the neons of seedy motels or liquor store signs. He mixes the cosy visions of the “good” Waltons-style household, and the perceived cartoonish “badness” of these “adult” spaces. The window here is crowded with caricatured fears, from within and without.

Anne Carson wrote that “eros is an issue of boundaries,” alive in the space between two things. Artist Prem Sahib

knows about the erotic power of the window as a boundary. In his 2015 exhibition Side On at the ICA, the artist set a small faux window into the wall, high up as if to emphasise that we are somewhere below ground. Soft-focus ivy caresses the other side of the glass, which is frosted to obscure looking. So much of Sahib’s work deals with spaces where queerness is played out, such as cruising sites or clubs, where a lot hangs off just the way you look at someone. If Sahib’s window were real, you wouldn’t be able to see much through it, but the temptation might still linger.

- Left: Molly Soda, How I Stopped Being Self Conscious And Caring What People Think About Me, 2020. Right: Molly Soda, Opening Up (Vulnerable), 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

In 1985 Microsoft launched their famous operating system, and Windows started popping up inside the computer screen. Twenty-five years down the line, Tumblr-famous Molly Soda was regularly updating 30,000 people (myself among them) on the internet. Soda’s work since has played with the feelings of the thrill and anxiety induced by carving out a window into your life online. With her recent works at Jack Barrett gallery, titled How I Stopped Being Self Conscious and Caring What People Think of Me, and Opening Up (Vulnerable), Soda physicalizes these online spaces as vinyl windows you might have in your home.

Beyond the windows lie flat digital renderings of bedrooms cluttered with delivery boxes and vlogging equipment; before them pot plants sprout in a window box. The bedroom scene, the pot plants and even the plastic-y window are at once vulnerable, real and fake. Here, the window opens onto an “authentic” self, but also onto aspirational selves—they all exist on both sides of the glass, which opens and closes with the push and pull of the self that we enact on and offline.

Then there are the windows of institutional spaces, which are perhaps maybe the most shuttered and guarded. Korean artist Haegue Yang’s work bypasses the window itself and reaches directly for the blinds—specifically the aluminium venetian blinds found in offices or waiting rooms.

There is something suspicious about Venetian blinds: the fragmented view you get through them, the way they can turn light into sharp swords that jut out across a room, the cinema trope of someone peering through the blinds at some terrible thing happening on the other side. But Yang makes them decorative. In Lingering Nous at the Pompidou Centre, the blinds were pastel pink and mint green, interspersed with strip lights, fixed together into an unfolding of barriers, and behind them nothing but more barriers. They seem to say something about the frustrations and obstacles to movement within a globalized economy where money travels more freely than people.

“Artists are playing with the window’s status as a boundary—of eroticism, aspiration, movement, fear and time”

Lighting is also used in Olafur Eliasson’s early work Window projection. A studio lamp projects onto the wall a rectangle of white light that is divided into smaller rectangles, like panes of glass. The work points to a fantasy of nature as a heavenly Eden, one that feels ever further behind us. Its physical element recalls film sets or photo shoots—spaces in which the popular imagination is shaped and constructed. Here, the window is no longer a threshold because the great outdoors is nothing more than a trick.

In the twenty-first century, windows have retained their ubiquity in art. But more than treating them as frames to inspiration, artists are playing with the window’s status as a boundary—of eroticism, aspiration, movement, fear and time. Commentators like Arundhati Roy have called for us to see the pandemic as a window or portal into a new world, for better or worse—and so it may be. Right now, though, I am staring out of the actual window at the overground station near my home, and have never longed so hard for a view of London from that slow-moving train.