As we launch the food-themed summer issue of Elephant magazine, we are thinking a lot about the present state of the food industry and, of course, its possible futures. In discussing topics such as sustainability, veganism and factory farming, one foodstuff comes to mind again and again: milk. Is milk the most political edible of all?

While milk historically has had something of a wholesome image, in recent years this has been changing fast. It has been claimed that dairy cows have been bred to produce up to ten times the amount of milk than they naturally would—something which inevitably puts an ungodly strain on the animals themselves, not to mention their many offspring. There are countless reports

online about the swathes of male calves that are killed shortly after birth, as surplus to the trade. A whopping third of all UK consumers now buy plant-based milk (although a quick look at the statistics highlights an undeniable economic element within this trend: people buying plant-based milk will typically spend forty per cent more on their overall shop, suggesting there is also a means-based aspect to this.)

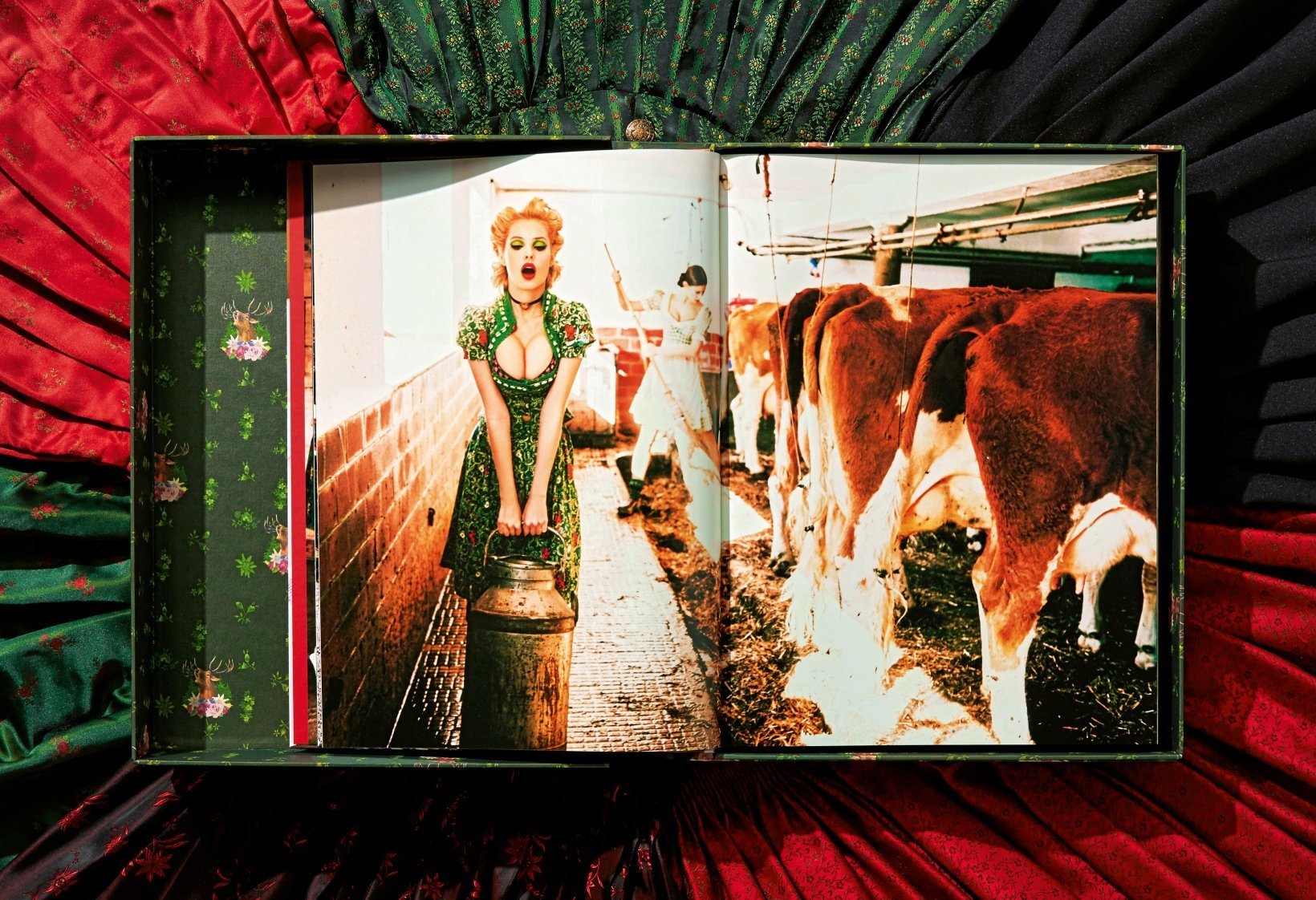

- Above: Marianna Simnett, Blood in My Milk, 2018. Still 5-channel HD video instillation; Below: Honey & Bunny (Sonja Stummerer & Martin Hablesreiter). Image by Daisuke Akita

“The innocent and childlike connotations of milk are routinely perverted and subverted by artists”

The political symbolism of milk, from ethics, to sexuality, wellbeing and even skin colour, has been a long and rich source of inspiration and interrogation for artists. A good place to begin, in a discussion about milk, is surely at the source. Dairy farms are unusual spaces. We consume their produce on a regular basis, but very few of us have ever been inside one. We may have ideas of what these spaces look and feel like from various videos posted on social media by platforms such as Peta and the Dodo, but most of us have never experienced one first-hand. They are often indoor spaces, inhabited by a growing number of machines. It is perhaps the uncanny nature of these factory-like building that have proven them to be such a big influencer on artists over the years.

In her dreamy 2014 video work The Udder, Marianna Simnett filmed at a partly automated Sussex dairy farm, playing with the line between man and machine. “I was looking for small, family-fun robotic dairy farms,” the artist told Elephant in a 2018 interview. “Most are either DIY or full techno. I was after something in the middle, hand methods that were starting to be replaced by robots.” Within the work, the artist explores themes such as purification and corruption. Both topics are hugely connected with milk production—it is a drink associated with children and innocence, yet in its pre-packaged state it is often full of pus (an estimated third of diary cows suffer from mastitis). The use of children in the film creates a strange tension between the different realities and versions of innocence at play—between the children, their near-puberty, the life-giving substance of milk and the animals who create it. Innocence slips into something else in the film, towards something violent and unsettling, as a teat and a young girl’s nose are both sliced off.

“Can we only make peace with it if the source of the milk is seen as nothing more than a machine?”

Despite the perpetuation of horrific hidden-camera farm footage available online, the wholesome and innocent farm imagery that stems from childhood books and cartoons perseveres. On the one hand, images of plump, happy cows and pigs appeal to the instinctive love that most children have for animals. But this imagery provides a dual purpose, allowing for a practical yet sensitive and compelling way of enlightening children (to some extent) about the source of their meat and dairy meals. In these books, the animals often wear exuberant grins, and the farmers are gently hands-on, as cows are milked by hand, often with a whole barn to themselves. The same kind of imagery is also often used on milk and dairy packaging, with portly, happy animals slapped on the labels.

Austrian artists Honey & Bunny (Sonja Stummerer & Martin Hablesreiter) create video works which playfully confront the systems and processes that we have around food and eating. In one portrait of Stummerer, the aforementioned farm idealism and harsh realism are brought together; she stands in the foreground next to a very healthy-looking cow, both lit by the golden, heavenly light that streams through the big windows of a wooden barn. Yet this image is punctured by the loaded shopping cart that Stummerer stands at, full of plastic-wrapped goods, and by the herd of cows that stand behind her, ear-tagged and gated into an uncomfortably small space: just another item of produce waiting to be milked or sliced up.

The innocent and childlike connotations of milk are routinely perverted and subverted by artists, especially photographers, who play with it suggestively and mine it for its unfortunate similarities with another natural white substance, which is arguably less appetizing. Photographer/provocateur Ellen von Unwerth has long used the milkmaid trope in her work, photographing young, buxom blonde models in full Bavarian get-up, holding up big pails of milk and occasionally dribbling the substance from their mouths. As with all of Von Unwerth’s photography, these images propagate the stereotypes they send up, with a cheeky wink to porno “facials” and debased purity. Of course, the hand action of the milkmaid is often compared, suggestively, to a sexual move. In another Von Unwerth series, we see a young Kate Moss in a short dress, crouching down and sipping from a bottle of milk by an open fridge—a knowing side-eye alluding to the sexual provocation of the image—as she wipes her mouth.

The complex nature of milk is dissected by David LaChapelle in one of his most famous images, which plays up to the strangely icky reaction we have to human breast milk, as opposed to the collected juices of another animal. In Milk Maidens (1996)

, two big-haired models pose alongside one another, one squeezing milk from her bare breast into the cereal bowl of the other, who gasps in wide-eyed astonishment at the camera. Somehow, in this image (as in life), the idea of drinking cow’s milk seems like the normal activity, while the idea of drinking human breast milk is both gross-out and deeply sexualized.

This contradictory idea is also explored in a throwaway moment in Bojack Horseman—the animated Netflix show that loves to blur the lines between “animals as animals” and anthropomorphized animals—when the human-like cow/waitress who is serving in a cafe suddenly whips out her udder and squeezes some fresh milk into a waiting glass. Perhaps milk coming from a being with a perceived personality is when it gets weird? Can we only make peace with it if the source of the milk is seen as nothing more than a machine?

This contradictory idea is also explored in a throwaway moment in Bojack Horseman—the animated Netflix show that loves to blur the lines between “animals as animals” and anthropomorphized animals—when the human-like cow/waitress who is serving in a cafe suddenly whips out her udder and squeezes some fresh milk into a waiting glass. Perhaps milk coming from a being with a perceived personality is when it gets weird? Can we only make peace with it if the source of the milk is seen as nothing more than a machine?

Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg elevate milk from the erotic to the deviant in their work. Passing Comfort (2016) hints towards adult baby games, as a tiger in a pink satin bonnet and briefs clutches a bottle of milk and looks naughtily to one side. In the Swedish artists’ sculptural work Worship (Sausage in Milk), they are even less subtle, as a long and erect fabric and resin sausage stands upright in a glass of milk.

“The idea of drinking cow’s milk seems like the normal activity, while the idea of drinking human breast milk is both gross-out and deeply sexualized”

While these allusions around drinking and spitting milk are playful in a sexual sense, the act of spewing milk can also be seen as pure aggression. In the words of Jenny Holzer, “Spit all over someone with a mouthful of milk if you want to find out something about their personality fast.” In short, it’s likely to enrage. Indeed, milkshakes have recently been used as a means of political protest, leading to the hilarious term “milkshaking”. In late May, one of the banana and salted caramel variety was lobbed on right wing British politician Nigel Farage. Following this, protesters took to surrounding his Brexit tour bus, armed with the sweet, creamy drinks, and “trapping” him inside. The craze has now made its way to America. There’s something silly about milkshaking—the drink’s frothiness gives it a certain non-violent air when used as a weapon—but it’s also humiliating, a liquid that quickly sours, turning its victim stinky and, visibly, a bit spunky.

Valie Export also plays with darker connotations of milk to make a political statement in …Remote…Remote…, as she repeatedly mutilates the skin on her fingers, plunging the bleeding cuticles into a bowl of milk, as the red and white mix together. “These are the very fluids of femaleness: lactescence (maternal) and menstruation (sexual),” says Régis Michel of the work. “But these barbaric weddings are more than a mixture: a metamorphosis. Valie Export turns milk into blood. And the body into tragedy.” As Barbabra Creed writes in her essay The Monstrous-Femenine (quoted in Emily Gosling’s essay in Elephant’s issue 39 about kitchen horror in film), “One of the strongest of food taboos relates to the ancient imperative that blood and milk should be kept separate.”

- Valie Export, Remote...Remote...Remote, 1973

Milk has even been used as a powerful way to discuss skin colour. The whiteness of milk, and this whiteness as a symbol of cleanliness, is explored in a famous image of Whoopi Goldberg, taken by Annie Leibowitz in 1984. In this work, we see the comedian and actress’s arms, legs and widely-grinning face bursting from a milky bath. The symbolism of the black actress bursting forth from this bright white substance is evident on first glance, but the work’s political references run even deeper, and there is a nod to one of Goldberg’s stage routines, in which she performed the part of a young black girl who uses Clorox in an attempt to turn her skin white.

Throughout all of these works, it feels as though it is the idealized image of milk—clean, nourishing, innocent—that appeals so much to artists. Hidden within this, are a host of inconsistencies and hypocrisies about the substance, from the way it is produced, right down to the apparent purity of its colour, that enable artists to convey all manner of things about ourselves and the world around us. When we begin to expose these, the substance itself begins to feel more than a little sour.

![VALIE EXPORT_Remote_Remote_19.15.33[1]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/VALIE-EXPORT_Remote_Remote_19.15.331-1200x900.png)

![VALIE EXPORT_Remote_Remote_19.16.56[1]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/VALIE-EXPORT_Remote_Remote_19.16.561-1200x903.png)