For hundreds of years the fireplace was the focus of the British home. Before electricity this vital source of light and heat commanded a nightly social gathering, and while the flames kept their utilitarian function, it was the elaborate architecture surrounding the hearth that soon gained its own significance. The aristocracy used intricately carved overmantels, complete with mirrors, to demonstrate their wealth and power, while the general population made do by decorating their own mantelpieces with the objects that held special significance to them.

Until recently, this idea held true. Even as the need for a fire dwindled, the mantel offered a stage on which to impress the personality of the owner. China dogs, family photos, flowers, invitations, certificates and awards all found a place on this particular shelf, even as attention shifted towards the wonders of the home television set.

The importance of the mantelpiece in British culture is evident in the work of the pioneering social research organisation Mass Observation, whose first-ever study back in 1937 was titled the Mantelpiece Directive. Volunteers were tasked with documenting what appeared on top of the fireplace in everyday Briton’s homes, as a way of distilling the essence of ordinary existence across the country.

“These mantelpiece objects and arrangements are an altar to the interior, a landing strip for the everyday, a haven of domestic symbolism”

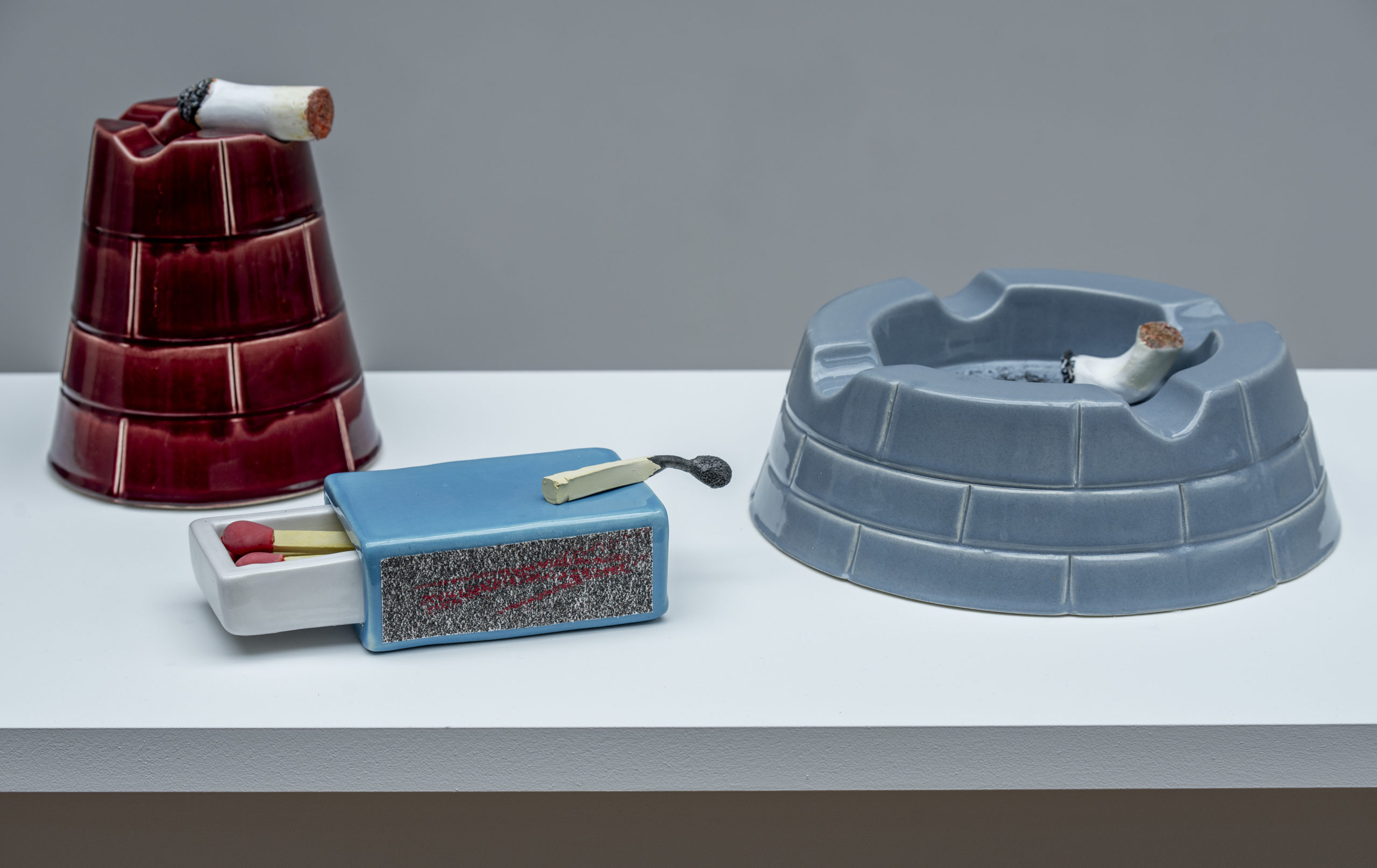

Artist Richard Slee has created a series of ceramic sculptures based on the subsequent files, inspired by intricately detailed statements and diagrams that include figurines, decorative jugs, matches, candles, clocks and much more. They are now on show at Bolton Museum. As Slee explains, “These mantelpiece objects and arrangements are an altar to the interior, a landing strip for the everyday, a haven of domestic symbolism.”

The fact that so many interviewees even had a mantelpiece is evidence of a particular time and place, before the post-war condition demanded new housing, and the principles of modernism

deemed a hearth old-fashioned and fussily Victorian. Nowadays, plenty of people consider a fireplace to be an indulgent accessory, or a fond memory that harks back to a grandparent’s chintzy living room.

Madeline Waller examines these nuances in her portraits of Bolton residents and their possessions, which are also on show in the museum. Using both still and moving image, she unpicks the way in which we display our most treasured items and how the aesthetic harmony of our interiors has changed over time. One sitter, Shonagh, still describes the mantlepiece as the heart of the house, regarding it as “your identity summed up in one place”. Her idiosyncratic collections include a series of Russian dolls featuring communist leaders, her children’s art projects and an antique metronome, reminding us that it is the intimate connection that a person places on particular objects that give them their value, not their monetary worth.

While Shonagh’s home features a traditional fireplace as a focal point, others have adapted. For instance, Jenneh balances a selection of accolades belonging to her father along the thin ridge of her electric fire, whereas Ganshyam incorporates the family shrine within a larger piece of custom furniture, which fills an entire wall. In these instances, it is clear that the idea of a mantel, whether or not it frames a fire, is still an important device for displaying our most prized achievements, hopes and values.

Nowadays, one could argue that while the primary function of the fire might have been removed, this all-important stage set still sparks the imagination. For example, painter Sam Nhlengethwa, who is famed for his pictures of South African life and the rhythmic power of jazz, recently took an introspective look at interiors, distilling various rooms to their very essence. In one such work, the unlit fireplace is the nucleus around which all other objects oscillate.

“It is the intimate connection that a person places on particular objects that give them their value, not their monetary worth”

Other examples can be found in Laure Provost’s The TV Mantelpiece, where moving image, ceramics, textiles, teabags and acrylic paint come together in a surreal technological tangle. Similarly, Susan Hiller’s spectral installation Belshazzar’s Feast, the Writing on Your Wall marries the performative power of the fire and the television, as eerie flames are broadcast on screen. In this moment, the two competing focus points of our contemporary domestic space become one, forming a single mantel that speaks to familiarity, mythology and human connection.

As digital technologies define a new era, where even a single screen cannot command the attention of a family unit, one has to wonder if the aesthetic balance that has defined our living space for so long will ultimately fracture. Perhaps the need for a primary focus will dwindle, and the principles of proud display will change. For now at least, it seems most of us continue to desire a physical space in which to present our most prized objects, and the mantel can still provide the warmth that we seek, whether or not a fire rages beneath it.