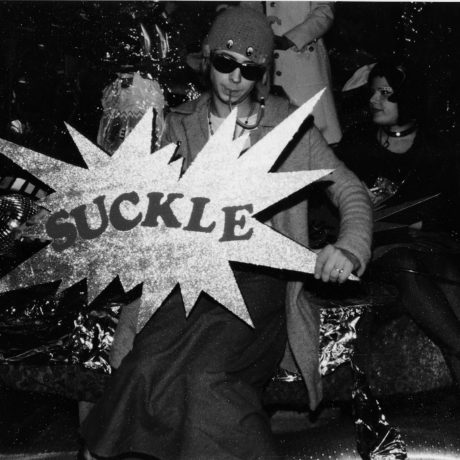

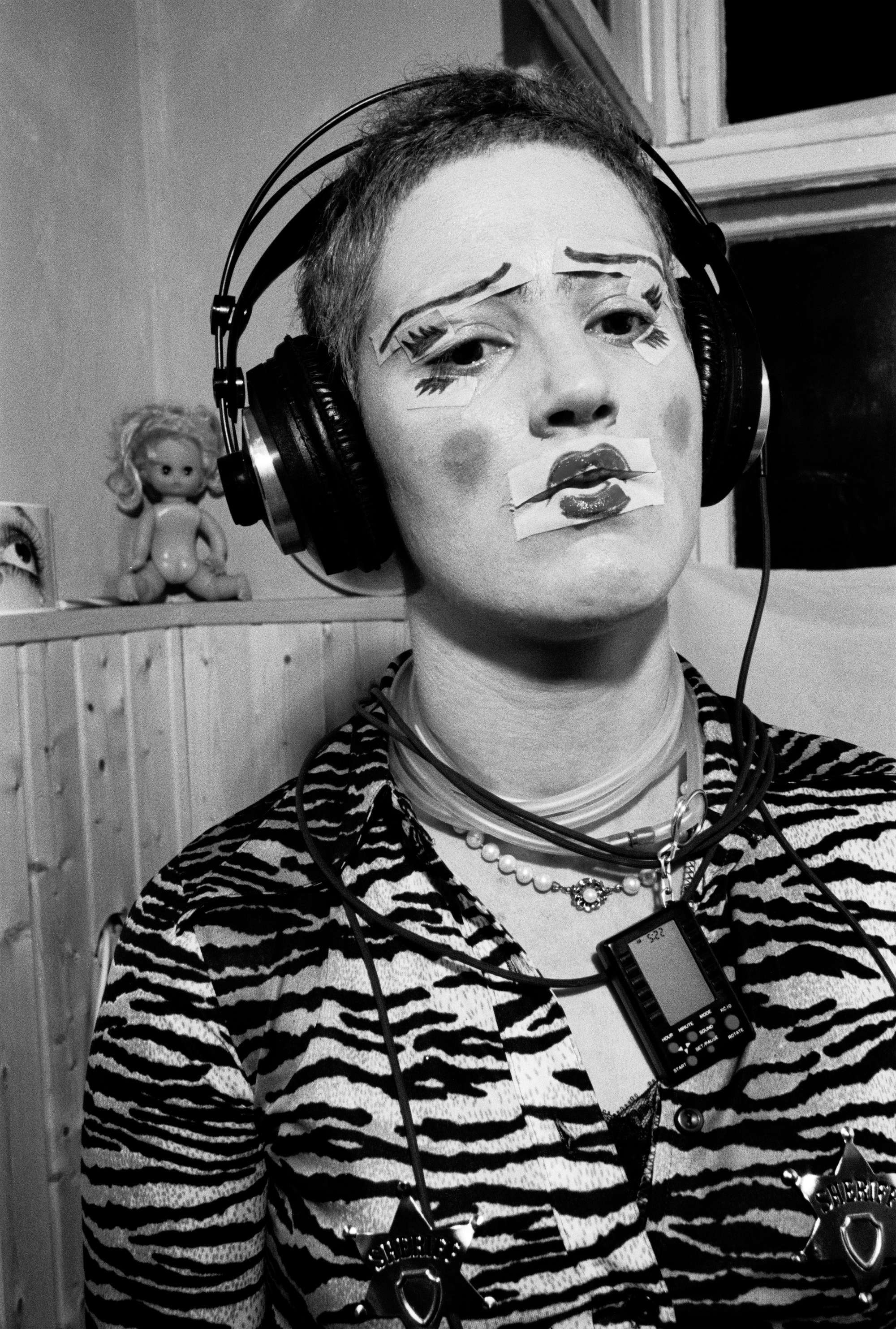

In Berlin, 1994, a group of artists formed Honey-Suckle Company (HSC), a movement that would operate in and between the contexts of fashion, music and art. Their name was plucked from homeopath Dr Edward Bach’s honeysuckle flower remedy, and the group saw the production and display of their work as part of a holistic healing method, or wellness practice, working outside of the mainstream art system and ignoring commercial restraints.

HSC emerged from post-reunification, pre-internet Berlin, where squatting was commonplace and property ownership rare. Their communal, DIY approach sat within a broader culture that regularly blurred boundaries between art and life, commercial and personal practice, the individual and collective. Their work would often take the form of an installation, happenings or the clothing worn by members of the collective in their day-to-day life, as well as showing in mainstream institutions, including MoMA

and the Berlin Biennale.

The tools and ideas employed by HSC were considered radical at the time, and contributed to a renegotiation of the relationships between art and life. But it’s difficult to engage with HSC’s anti-market, experience-led practice without it feeling distantly quaint—and even impossible—when viewed through the lens of our contemporary experience. Today, we find ourselves confronted with the hyper-marketed-self, “do-it-for-the-gram”, content economy. Advertisers will pay influencers to place their products; brands are buying out ball pits to create immersive Instagram experiences; pasta companies are collaborating on streetwear collections, everything’s been co-opted and spun into “spon-con”.

“The tools and ideas employed by HSC contributed to a renegotiation of the relationships between art and life”

The first survey exhibition of the group’s work, Omnibus, is currently showing at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. The show opens with a sand-filled, space-age stage set, infused with a dystopian edge. A group of mannequins and a giant cellophane bubble hover above a room painted pastel-pink and filled with stacks of televisions and photographs. It’s a chaotic archive of the group’s past activities, and emulates the DIY atmosphere of their early approach.

The exhibition includes a bright white, empty room-within-a-room, a void that you duck into. This work is purposefully non-commercial, and aims so pointedly towards an invisible void that it could come across as positively inaccessible. It’s also maintained some of the energy of the group’s original intentions, challenging what we will accept as art and what counts as an act of protest. It is a decisive shift against an otherwise stimulating, entertaining environment, and would be a challenge to turn into a marketable experience. Perhaps, it seems to suggest, the only radical act is to offer nothing at all.

We are living in the age of commerce, when fashion has become art, advertising has swallowed music, and room-scale installations have been taken over by brands. Mainstream art institutions have had to adopt these processes and presentation methods not to keep up with an underground art scene, but to align themselves with an insurgency of #content. It’s hardly the first example of an art and design utopia going awry.

The Bauhaus group never fully figured out their relationship to industry or the market, while Andy Warhol’s Factory was all too successful; Abstract Expressionism became a CIA tool

for promoting “the intellectual and artistic freedom of America” during the Cold War, and the Whole Earth Catalog—a counterculture magazine that encouraged self-sufficiency, alternative education and DIY attitudes—has been a significant inspiration to those conducting the rampant Libertarian tech hellscape that we see today.

In the 1960s, Artist Placement Group (APG) was founded, a loose network of artists who initiated and organized “placements” for artists in industry or public institutions. These placements involved the collaboration of artists with companies and organisations, where they acted as independent observers working to an open brief. They made the case for the mutual benefit of the artists’ presence, and argued for artistic practice to stretch beyond the studio or gallery.

APG were part of a broader movement towards site-specific and social practice, but they were distinct in their involvement with commercial, industrial and administrative contexts. Collaborators included the National Coal Board and Esso, and when it came to exhibiting its work APG would often showcase performances of negotiations between the artist and corporation. However, the ambivalent relationship of APG to institutional and corporate power revealed a lack of political clarity, and they were widely criticized for being too naive.

They also didn’t succeed in convincing business or government infrastructure of the long-term value of giving artists, or “incidental people” a seat at the table. Rather than bringing open, independent thinking to institutions and corporations, APG now reads as a prescient example of thinly veiled offers of influence being waved at artists in the interests of corporate power.

Artist Placement Group took a different approach to Honey-Suckle Company, but the tactics of both arguably paved the way for our neoliberal times. APG stated that “context is half the work”, but how meaningful is this when it lacks criticality? HSC sought to “reestablish a sense of trust in the future, in order to feel grounded in the present”, a sentiment that now sounds eerily reminiscent of something we’re likely to be told in a smartphone advert. Both APG and HSC had countercultural practices at their core, but they’ve also both been flattened out by the mainstream.

HSC thought they were doing the opposite: “Only something that is in constant movement, permanently reinventing itself, escapes the numerous procedures of inclusion and exclusion that the Western world has invented to discipline the individual.” But while they did, and do, continue to shift in approach, that focus on agility encourages spectatorship and continues to serve capital. Maybe the only way out is in, taking on the language and imitating the practices in a full-circle satire of the whole thing.

Rancourt/Yatsuk’s 2015 work Villagio, a performance sales pitch for a fictional tropical resort, closes the loop. The artists offered the achievement of “greater self-actualization through the ownership of luxury real estate”. The offering included helicopters, free daiquiris and a life-size sushi kayak, but it was never made clear what Villagio was, or if it even exists.

Meanwhile, Dillio Plaza by Slavs & Tatars, shown at this year’s fifty-eighth Venice Biennale, takes on the literal and visual language of perfume adverts and monuments to leisure in Western Europe, with their trademark use of humour and hospitality. Alongside the central fountain, around which you’re encouraged to linger on a plastic chair, there’s a vending machine dispensing pickle juice, adverts and giant monuments to pickles. Dillio Plaza satirizes its context by bootlegging its architectural style, mimicking its language with the meaningless tagline “What for others is style, for me is soul”. It offers up a space to relax and enjoy, whether you’re in on the joke, the butt of it, or just along for the ride.

“HSC’s sentiment now sounds eerily reminiscent of something we’re likely to be told in a smartphone advert”

Earlier this year, the artist Sterling Ruby launched his first clothing collection with a show at Pitti Uomo. The move came out of an earlier collaboration with Raf Simons in 2014, and a number of years of working with textiles as part of his art practice. He was interested in having “something going out into the world, and moving, and being something for people to see”, as reported by Vogue. It signals a return to the ethos of Honey-Suckle Company’s clothing collections, as well as their mistrust of the financial systems associated with art. But it’s also more cynical, feeds into the idea of art as a spectator sport, and embraces the individualism of the free market; Ruby both rejects the traditional gallery model and works with several simultaneously.

In a profile in The New Yorker, Ruby described the response from the galleries he works with: “The dealers were so mad at me,’ he said, laughing. But he found the result exhilarating. After the Simons runway show, he told a reporter, “Everybody was standing up, cheering. At that moment, I thought, fuck being an artist—this is wonderful.”