Mikhael Subotzky: Great to hear your voice Zoé, I just wish we could be chatting at a bar near my studio or somewhere along the Thames! Where should we start?

Zoé Whitley: I know, right? I keep thinking of our last major convo in your Subaru where we put the world to rights on entitlement and privilege, youth access to the arts, accompanied by an excellent radio soundtrack. This isn’t quite the same but I’m glad that tech makes it possible to stay connected. Let’s start by talking about some of your recent work?

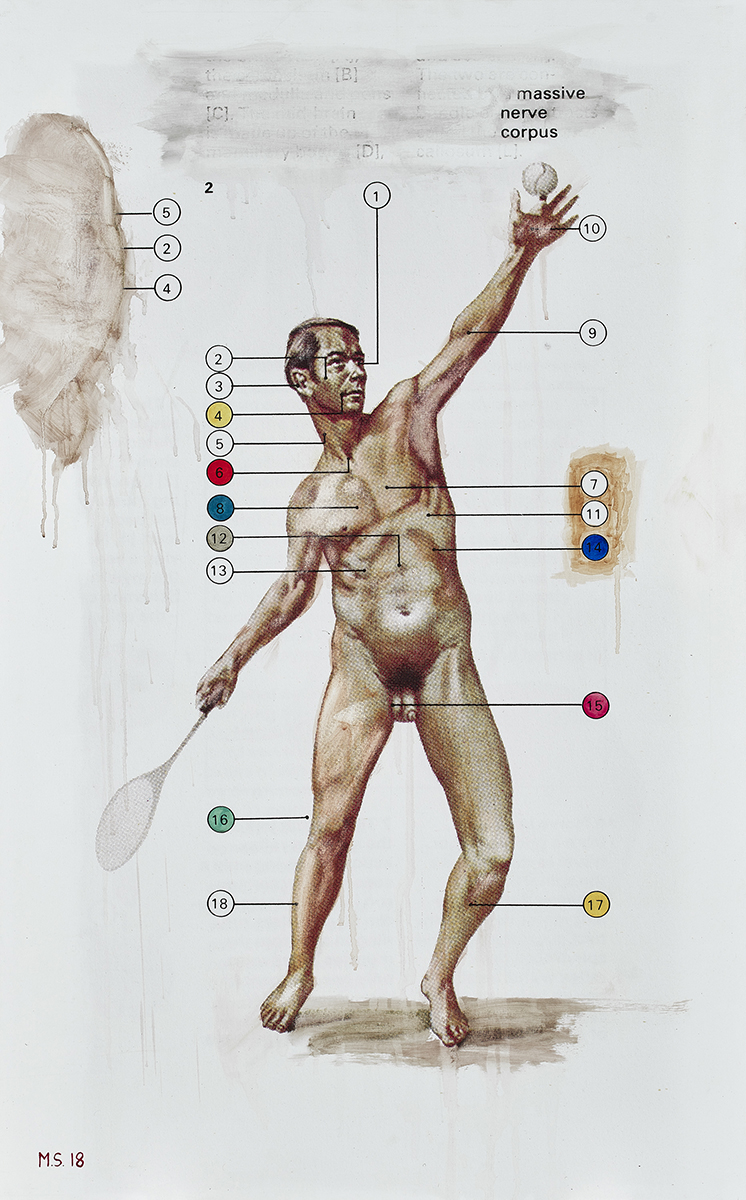

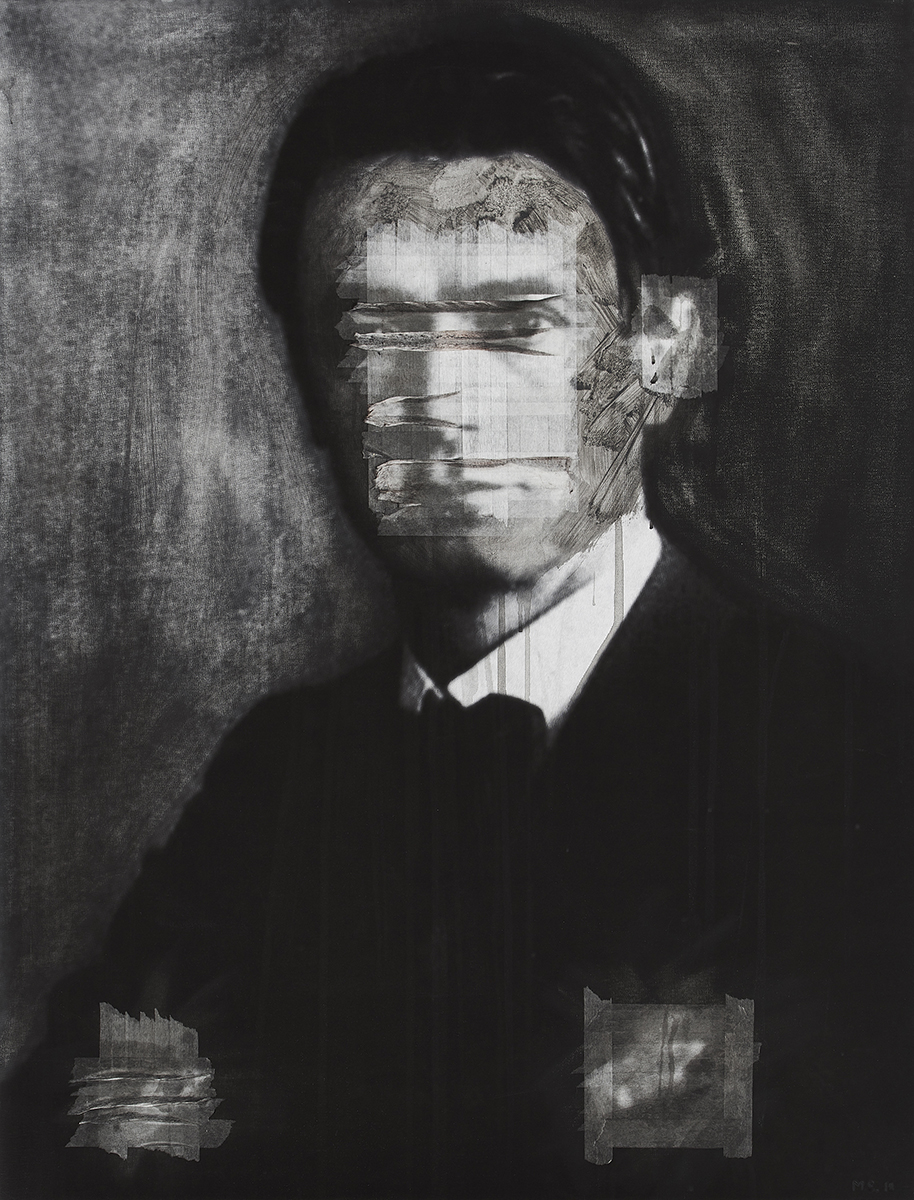

MS: As a white man, the question of my own presence in my work has been a tension for a very long time. In Massive Nerve Corpus in particular, I am busting through the layers of what that really means, and WYE [the 2016 film] was an important step in that journey. I’m interested in the relationship between white masculinity and vulnerability; how the lack of willingness to acknowledge the latter is one of the many reasons why white men have exercised power in such a destructive and violent way over hundreds of years. I’m looking at it in a historical context, and a very personal one.

ZW: The really productive conversations we’ve had discuss a lot of what often goes unspoken. I have certainly spent my whole life having opinions and responses to whiteness and maleness, from the point of view of my subjective experiences as a black woman. I’ve found the willingness to go through these layers to be incredibly illuminating in your work. In pieces like Retinal Shift there’s something bodily, like an exposed nerve, which is attuned to pain that resides close to the surface. There is an engagement with white resentment and fear, particularly in WYE. Funnily enough, it is black women writers who have led me to consider the nuances and contradictions of white maleness, like Kaitlyn Greenidge, Toni Morrison, Roxane Gay and Claudia Rankine.

MS: It really is black women writers who have got to the crux around whiteness. I have looked extensively at Nell Irvin Painter in the background to making Massive Nerve Corpus.

ZW: She wrote The History of White People, I was going to mention her too.

“What does it mean for whiteness to be elastic and expansive and absorb other groups when it needs to, but only to protect itself?”

MS: There are a number of things that she places in a historical context that make the construction of whiteness sound as ridiculous as it is. For example, where the word “caucasian” comes from. It is something a couple of old men dreamt up because they though Georgian women from the Caucasus were very beautiful. It sounds like I’m taking it lightly, but I’m really not. That word has had huge implications for many people. In Massive Nerve Corpus I’m trying to re-racialize whiteness, because whiteness as we know it disappears and becomes the obscured norm that you compare everything else to. When you start looking at its construction as a racialized thing, it completely turns our understanding of representation on its head.

ZW: It comes back to power. That is what Painter helps us to understand, in a way that is specifically situated and historicized. What does it mean for whiteness to be elastic and expansive and absorb other groups when it needs to, but only to protect itself? The Irish in America is just one case study, which helps to build a much deeper and more problematic sense of how whiteness is often used as a default.

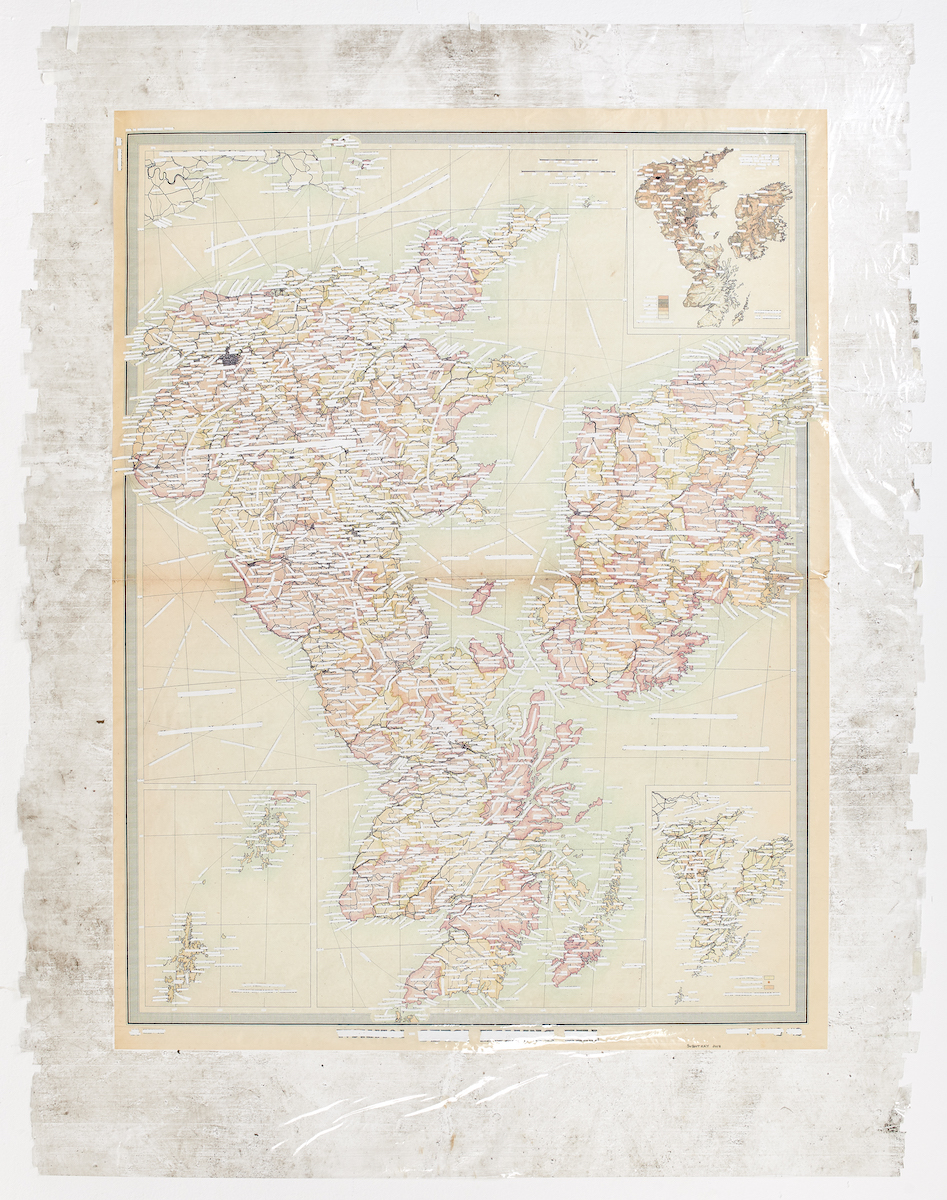

MS: It protects itself by—among other things—becoming invisible as a race. It becomes normalized. For this body of work, I have looked extensively at images from old encyclopaedias, which might look familiar in the context of the standardization of whiteness, but once you take them out of it, they look ridiculous. I read an interesting piece by Xaviera Simmons, in response to some of the criticism around the most recent Whitney Biennale. She says, “If radical change is truly desired in such a place, then those who have the bounty of privilege should shoulder the greater risk.” Black and African American artists and curators have been doing amazing work around rewriting the way the black body is seen in art historical canon. Zoé you have been essential to this! The flipside of the otherization of the black body, which we are all used to critiquing, is the normalization of the white body. I feel like something needs to be done to step up and meet those artists and curators, by making the racialization of the white body visible.

ZW: For so long whiteness was impermeable. Being willing to make it porous, and to talk about it in a way that isn’t designed to restore a form of superiority but rather make it part of a more complex matrix, is very important. This comes through in your work, in how you relate to materials. Whiteness is not some unbreakable or unknowable bastion of humanity, it is messy and flawed and needs to be broken down and understood.

MS: Absolutely. I started off in the mode of documentary photography, and I’ve really had to question why I was doing it, not to invalidate it, but to be honest—looking in as well as looking out. When I made the film Moses and Griffiths, it was a revelation. It is a portrait of two black men in their seventies. In representational terms it is not that different from the photographic work I was doing before, but the medium of film and the collaborative way that I used the process allowed them to tell their stories.

ZW: You demonstrate a fundamental respect in the way that you take up space, which elicits a mutual respect from your subjects. You accord them quite a lot of agency—which is deserved. Ponte City [a photo series created with Patrick Waterhouse that documents life in the notorious Johannesburg residential skyscraper] was an artistic collaboration, but you also collaborated with the residents. The way that this trust was built up is felt in the work.

MS: I was very aware of that when I was working on Massive Nerve Corpus, as a white man trying to critique white masculinity in a big gallery in central Johannesburg. The question of how one takes up space is very relevant to white male artists—we all need to think about what our responsibilities are. To jump back to Moses and Griffiths, concerning the way I have worked with people over the years, it is more about how I want to live in the world, as opposed to what kind of artist I want to be. For example, my relationship with Hermanus, a man that I photographed as part of my ex-prisoner documentary film project in 2005. Through our ongoing relationship, it came to me to write a character that was based on him for WYE.

Hermanus acted this part. He jumps from my documentary practice into the fictional film. He plays a really important role, because WYE is an attempt to get inside the colonial gaze. You have three different protagonists and three different temporalities, all looking at the landscape with different degrees of expediency. The whole film turns around Hermanus, but we never get inside his mind or know what he is thinking. It was vital to allow him to have his own thoughts, which we don’t have any automatic right to hear.

ZW: Which is the opposite of what is going on in one of the other narratives on another screen—where we watch Craig Hare (a white character) writing an email to his aunt in Australia. And he’s trying to self-edit…

MS: Yes, exactly. We can see as he cuts things up and changes the wording. It tells us so much about the way many people in the world think. It was quite a moment when I realized I could do that. Essentially, it’s rather boring to film a guy writing an email.

ZW: But this is something that the medium of moving image allows us to see in real time. We don’t have to deal with his thoughts through a voiceover or a re-enactment of the justification he is giving. You are seeing how he would explain it to someone else, and how he is thinking, “Oh, I shouldn’t say that, so I’ll put it in these terms.” To view all of the layers of the onion, you are able to see the racist kernel of truth at the centre.

“It is so telling that white people get more riled up about the suggestion that they are racist, than about actual racism”

I have always been a fan of multiple perspectives; there is truth in each subjective position. The thing that stuck with me was actually understanding the narrative of someone who is migrating to an exclusively white place, with the irony being that the population is white because they have displaced the indigenous population. To have these insights into someone seeking to justify this position makes me think of something Roxane Gay said: It is so telling that white people get more riled up about the suggestion that they are racist, than about actual racism.

In WYE you see these things that I would certainly never normally see. That tension between the opacity of the Hermanus character and the centrality of the white characters made sense in relation to the story. I didn’t view Hermanus as a kind of “magical Negro” trope, but precisely as this figure who is driving so much of what is happening.

MS: Yes, and how do you engage with the history of these tropes in a way that can both destroy them and reveal what is insidiously hiding behind them. For me, filmmaking is something that different works can rotate around to engage these things on multiple fronts. For example, White on White (or Blessings of Emigration to the Cape, after Cruikshank) is a large painting based on a cartoon that I discovered in my research for WYE. It depicts supposed dangers facing immigrants to the Cape, specifically the English who came here in 1820. These incredibly racist renderings show black “savages” attacking the settlers, the ultimate trope of the nineteenth century colonial imagination.

I took this image, enlarged it and printed it on canvas. I scrubbed away at the black figures until I was down to the bones of the canvas. They became white, intertwined in this cloud of whiteness, which envelops everything. It was an incredibly difficult and scary work for me to make. Obviously, it is dealing with subject matter that is very painful for a lot of people and I had to ask whether I, as a white man, could comment on this. But this is the crux of it, like with my handling of Hermanus’ opacity, I hope I am showing that these things are figments of the white imagination, and how white fear is at the centre of this long and ongoing history of violence.

ZW: We need a reading list. There’s an excellent book by Robin DiAngelo called White Fragility. There are times in my life where I feel like I just need copies of it in my bag to hand out to people!

MS: That is a great thing to do, because publications like Elephant need to start a conversation.

Reading List

- J.M. Coetzee: White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa

- Robin DiAngelo: White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

- Aruna D’Souza: Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts

- Richard Dyer: White: Essays on Race and Culture

- Roxane Gay: The Racism We All Carry in Bad Feminist; Guardian interview with Aida Edemariam

- Kaitlyn Greenidge: We Love You, Charlie Freeman; Who Gets to Write That? The New York Times

- Toni Morrison: Mourning for Whiteness, The New Yorker

- Nell Irvin Painter: The History of White People

- Claudia Rankine: I Wanted to Know What White Men Thought About Their Privilege. So I Asked., The New York Times

- The Racial Imaginary, The Whiteness Issue, September 2017

- Koketso Sachane: seven-part podcast on racism in South Africa

- Xaviera Simmons: Whiteness Must Undo Itself, The Art Newspaper

- Mikhael Subotzky, interview with Hanso Umberto Oberist