Your paintings create quite an Orwellian image of society. Do you feel they’re a representation of where we are now, or are they more a warning about a possible future?

It depends on the specific painting, but both. Some are warnings, some serve as speculations, others as depictions of past events. They are Orwellian, I suppose, in that they consider power structures. In many instances I am talking about authority and my general sceptical view towards so-called authority figures.

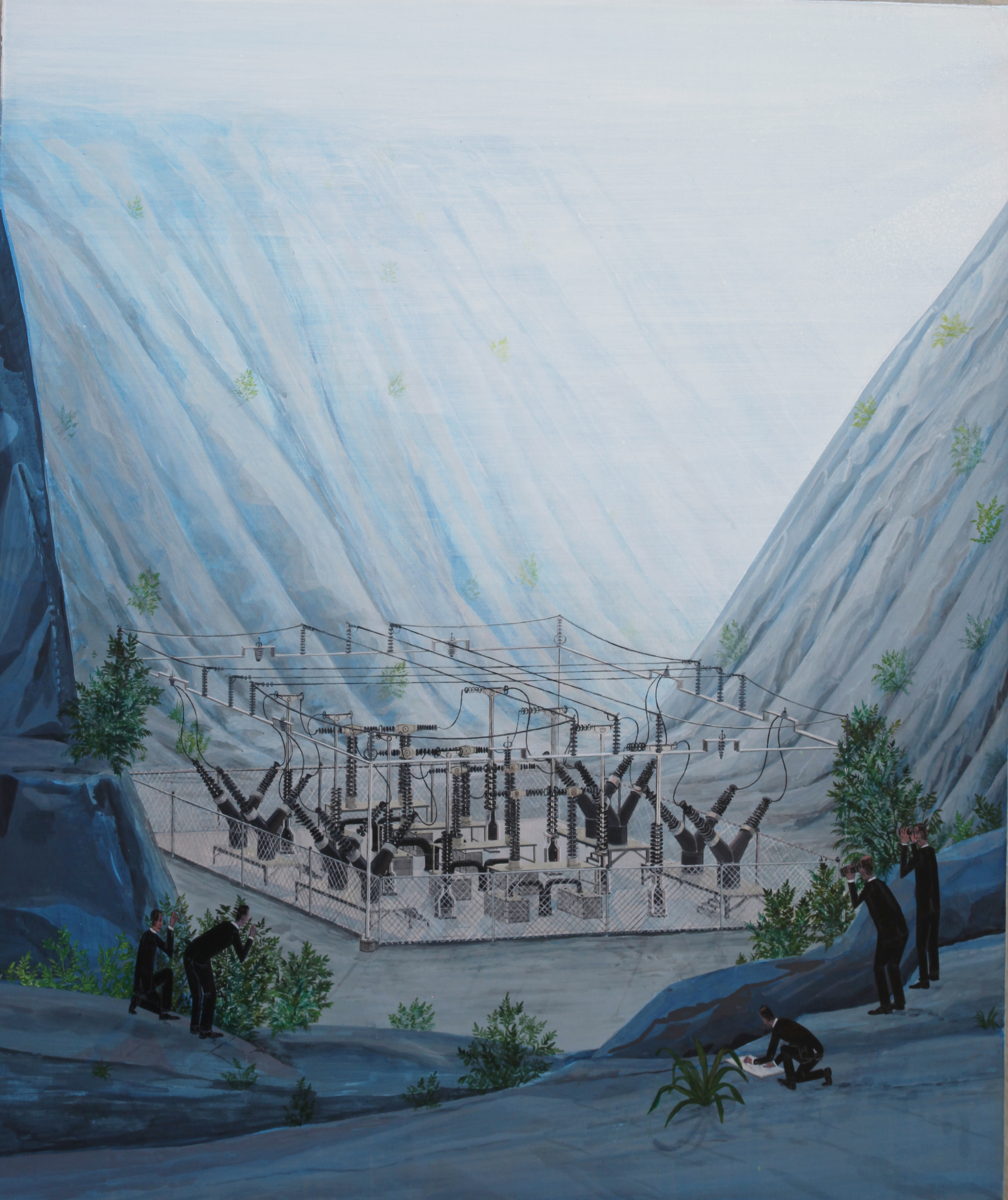

It feels as though there’s a tussle between nature and the human-made in your pieces. Sometimes they’re rigidly structured, at other times the natural world looks to be carrying everything away. Which do you think would win out eventually?

Nature will win in the end. That’s the reminder. We are temporary. I’m drawing a distinction between the rigidity of the power structures we create and the inevitability of nature popping up to remind us who is in charge. Sometimes the little bits of nature are creeping back into a space where they’ve been eliminated. There’s a subtle reclaiming going on. There’s no question about who would win out, if we are looking at it that way. I’m not sure I see it as a tussle, though. It’s more of a reminder.

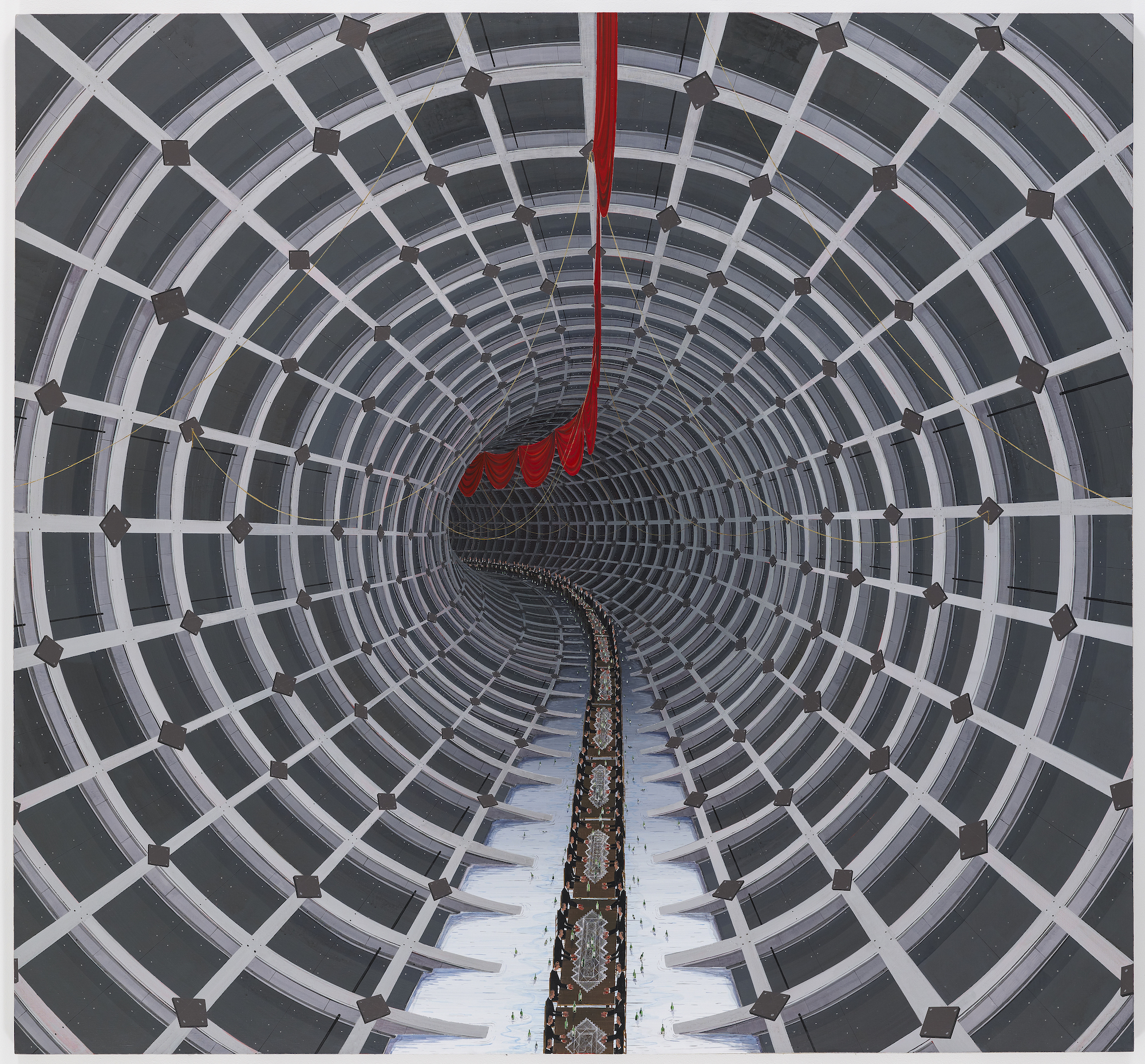

I was interested to hear the story behind Projection. Although most of your paintings feel universal rather than specific, do you often take real-life stories or events as your starting point?

Projection was directly influenced by the actions of one of our most unenlightened politicians in America, the Governor of Maine [Paul LePage]. He had ordered some murals to be removed from a government building because he didn’t like the pro-worker message of the painting. Apparently bosses and owners are the ones we should celebrate. The “makers”. He had this mural removed from the building, so in retaliation the artist projected the image of the mural on the outside of the building. I just changed the circumstances and details but liked the image of that. I’ve turned it into a question about science, or just facts in general. Sort of like “Here’s the Moon, can we all agree that this is the Moon?” because you can’t assume anything anymore. People are far afield of the truth about things.

Why are the characters in your paintings generally male?

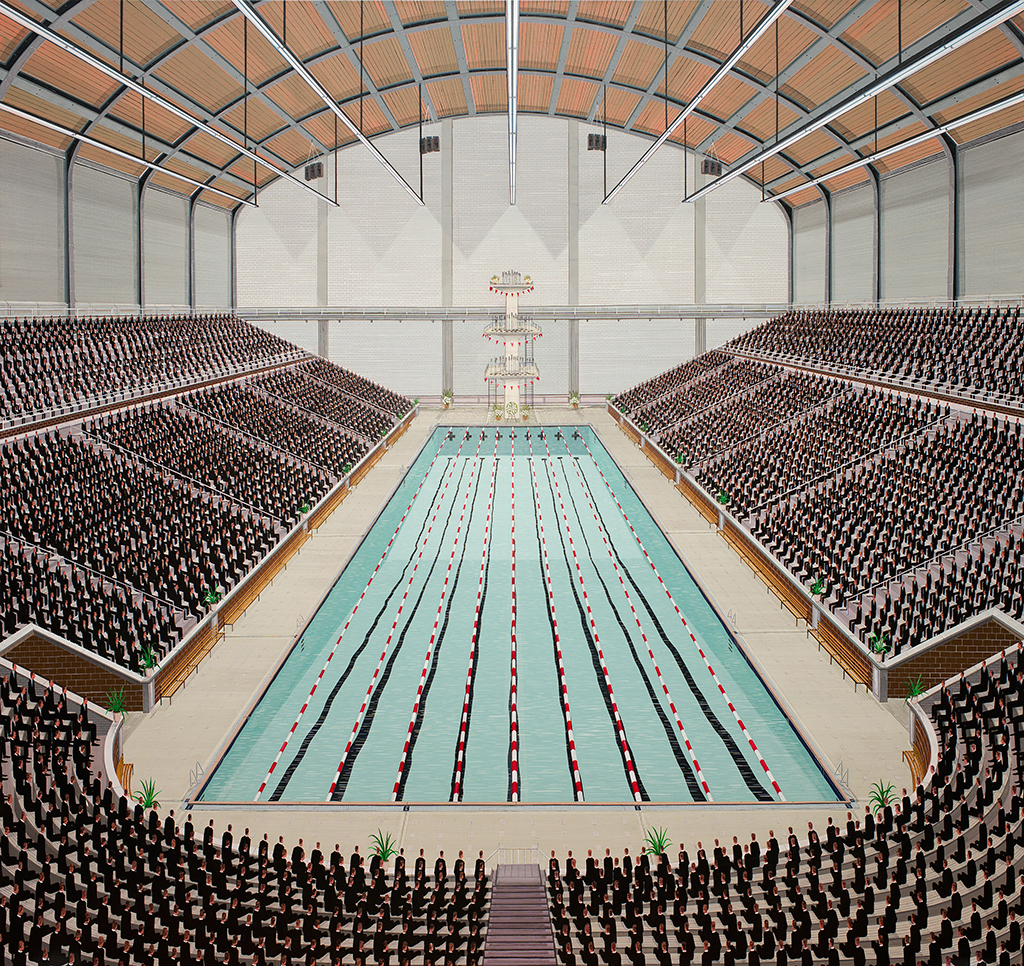

Because they are generally critical of power and authority. In my lifetime and experience, most of the things (actions, crimes) I am portraying place the white male squarely in the position of responsibility. They aren’t individuals in any sense (the men in the paintings, not white men in general). They are the bodies whose purpose it is to support whatever ridiculous action is being portrayed. Once I feel that I’ve given the brunt of the blame to white guys, I’ll move on. The people serve several functions other than populating the scenes I’m describing. There are formal reasons too—clarifying the sense of scale, creating a rhythmic quality. Music influences these as well. Creating overlapping patterns and weird vibrations.

“It would be hard to call paintings this fussy and controlled ‘spontaneous’, but they are not at all planned out”

The responsibility of the white male is particularly relevant right now, and has been very present in discussions around Donald Trump’s election. Do you feel your message is more urgent than ever?

I spent the first few days after the election in a sort of shell-shocked state, like a lot of people. It feels in a way like my worst fears have come to pass. It seemed like “why bother?” until I got back into my studio. Everything was the same. In fact, everything had a fresh charge. It wasn’t hard to figure out that these are maybe more valid than they’ve ever been. Maybe they’ll be seen differently now, or maybe they will seem less funny and more scary. Who knows? I see them differently now myself, but plutocracy and white male power were preoccupations of mine well before this particular shit show.

- Left: Inland, 2014; Right: Narcissists, 2015

Your paintings are meticulously formed. Do you have a very strict process early on for deciding exactly how they’ll look or are you spontaneous as you paint?

It would be hard to call paintings this fussy and controlled “spontaneous”, but they are not at all planned out. I’m figuring them out as I go. Since the physical work part of making these is so labour intensive, I need to find variation where I can. If I think about the paintings in my studio right now, one is pretty much a copy of a photograph, a couple are completely made up and a couple are based on a combination of images. I have an idea to begin with but the strategy is to commit to half an idea. I’m pretty much making them up as I go. With this method, I can feel a bit like the idea comes to me rather than the other way around. I start them with no plan of how to finish them.

Who are your main influences?

René Magritte, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Horace Pippin, Giorgio de Chirico, Caspar David Friedrich, Orson Welles, Arthur Lee, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Joseph Campbell… Lots of people. Stanley Kubrick, Joanne Greenbaum, anybody who has some quality in their work that I can use for my own purpose.

This feature originally appeared in issue 30

BUY ISSUE 30