Brit musician/producer/Mo’ Wax label founder and curator James Lavelle is sipping cola and chatting in London’s Saatchi Gallery restaurant. We’re surrounded by artworks by the likes of Jonas Burgert, John Isaacs and Norbert Schoerner, all taken from Lavelle’s immersive walk-through installation that transforms the entire floor above us; Beyond the Road

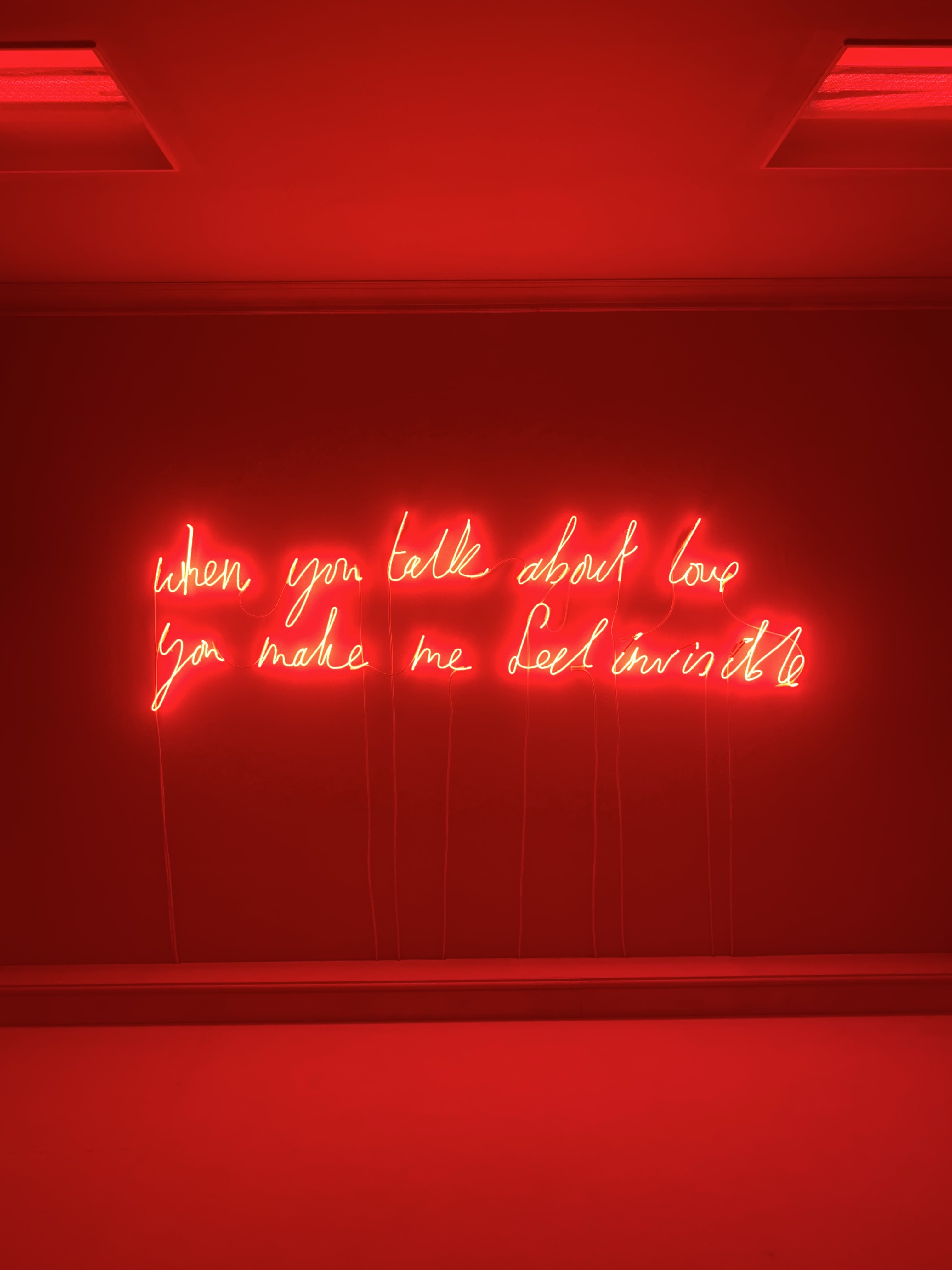

is a sprawling multi-sensory collaboration with Punchdrunk theatre’s creative director/producer Steven Dobbie and Colin Nightingale. Behind his head, a neon sign shimmers: “Feel more / with less”; it’s taken from a track on the latest album from Lavelle’s outfit Unkle: The Road: Part 2 (2019)—this record, and its 2017 predecessor, form the driving force of BTR.

- Beyond the Road. Photo by Julian Abrams

“I hoped to create something here that was like a universe”

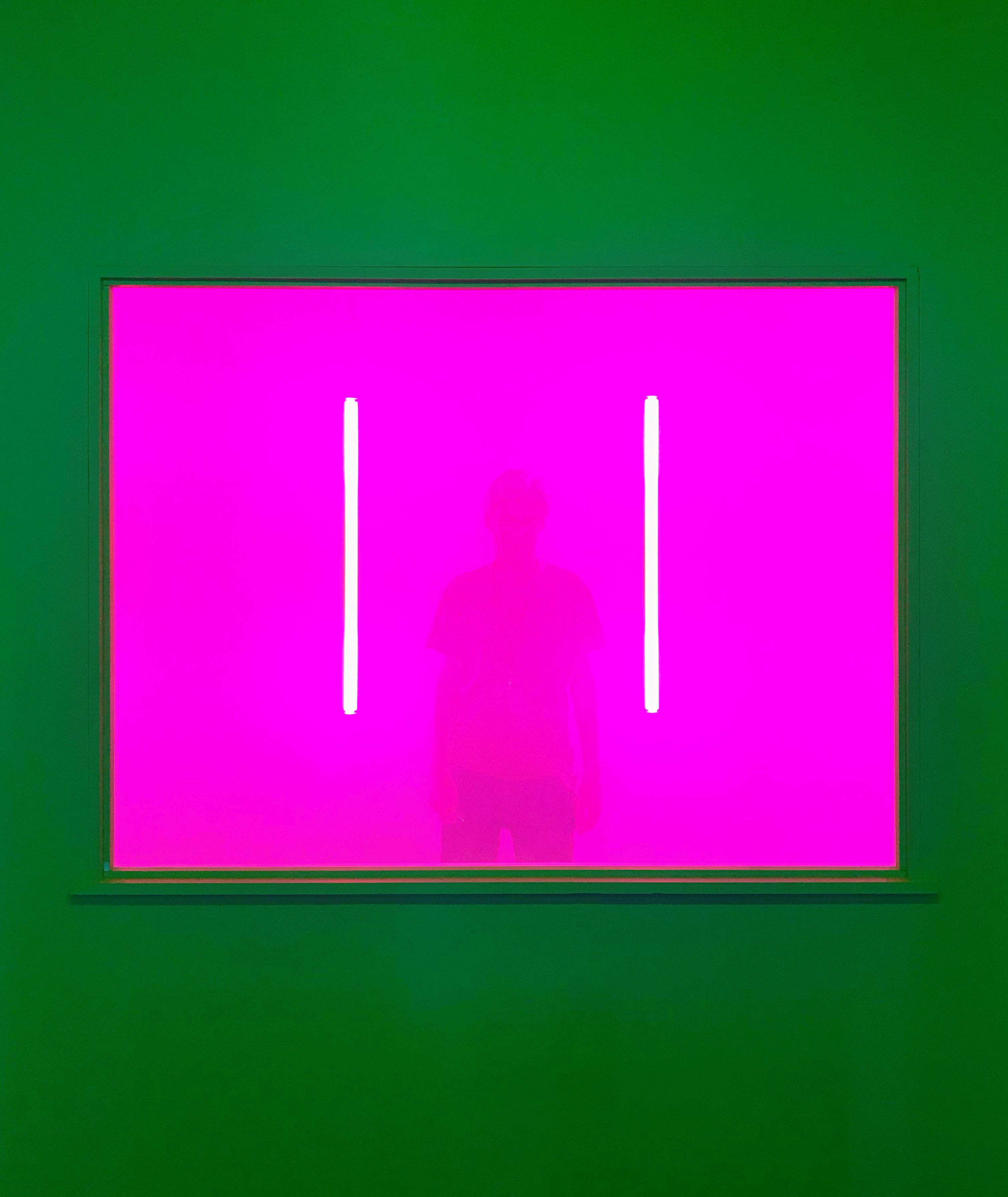

I’m taking in Lavelle’s softly-spoken, enthusiastic conversation, though at the same time, my head is swimming slightly. I’ve just stepped out of BTR, and its sensations haven’t entirely left me. The installation feels like succumbing to a fever dream; the music of The Road: Parts 1 & 2 flows and seeps through every space in the installation, and sounds intensely beautiful, raw and bluesy—you create your own audio “mix” as you move between areas or pick up props including a payphone. I found the experience swoon-inducing, and immensely unsettling—not least when a close encounter with a creepy animatronic was followed by apocalyptic strobing effects. At certain points, the stark lighting and angular designs recall the cinema of Stanley Kubrick; indeed, Lavelle did curate the grand-scale Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick group show at Somerset House in 2016.

“I hoped to create something here that was like a universe,” he murmurs. “There isn’t a painting, or neon sign, or smell in there without a reason. The reason why there’s a painting of a headless horseman [the cover visual for The Road: Part 1, created by Berlin-based artist Burgert] is that I split up with a band; that painting represents me going out on my own with a skeleton and a young child: the old and the new. This is an experience that has an autonomy, in that anyone can walk into it—but I also want to tell a story within the work.”

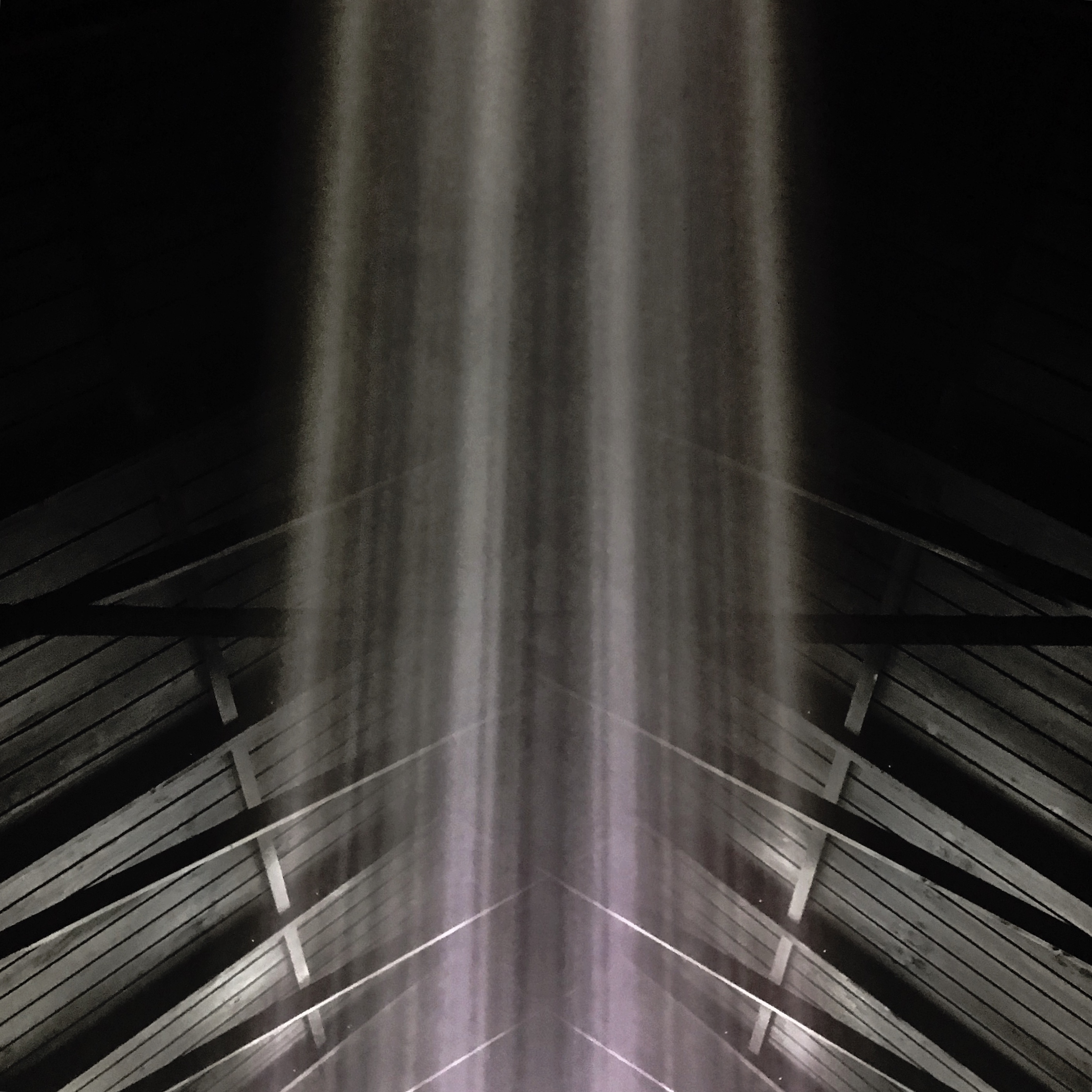

The story behind BTR’s creation began when Punchdrunk’s Dobbie and Nightingale approached Lavelle at his film playback for the first instalment of The Road (created with long-time visual collaborator Doug Foster, who also creates arguably the most mesmerizing element of BTR, projected within a wooden Southern Gothic “chapel”).

“This is an experience that has an autonomy, in that anyone can walk into it”

“Colin and Steven asked if I’d be up for reacting to a work in progress,” explains Lavelle. “I didn’t know what to expect, other than I liked them creatively…” He gave them the audio stems for a couple of The Road’s tracks, and later, Lavelle was called to Punchdrunk’s development HQ in North London. “They’ve built an entire village—if you imagine something like The Wicker Man; it’s highly detailed, like going onto a film set,” he says. “They’d been working with Tupac [Martir], who does a lot of my lighting. I went into this blacked-out space, and suddenly lights came on, with the sound of The Road going between all these different buildings. I was really excited about this idea being developed… What I love about this show, and working with Colin and Steven, is being led by the music first. There aren’t actors, there isn’t a performance. Look, this room’s beautiful,” he says, gesturing around the restaurant, “but when you put it into the context of BTR, it’s like going into the imagination.”

Lavelle’s fascination with placing music and art into different environments is also pretty deep-rooted, including his 2010 multi-media exhibition Daydreaming at London’s Haunch of Venison gallery (which featured collaborators including graffiti pioneer Futura 2000, filmmaker Jonathan Glazer and Massive Attack’s 3D).

“There’s always been a narrative of trying to create spaces within spaces, so it doesn’t feel like you’re just putting stuff onto white walls,” he explains. “It started for two reasons: firstly, purely creatively. Secondly, because you realize how ‘disposable’ music is, as a generalization; I was intrigued about putting music into a different environment, how to make a record into an installation, and the way that people would spend time engaging with the work and its emotion. You might have a hardcore fanbase, alongside people who don’t necessarily know the catalogue.”

BTR isn’t exclusively pitched at Lavelle/Unkle devotees, but it is studded with details that they’ll relish; a sequence from the Oscar-winning movie Roma, for instance, is accompanied by the haunting On My Knees featuring Brit indie-roots talent Michael Kiwanuka: Roma director Alfonso Cuarón approached Lavelle to create this song, inspired by his film. The multi-media approach also reflects a continuity (and a dogged determination) throughout Lavelle’s career; he put on his first art exhibition (by NY graphic designer/graf artist Eric Haze

) when he was eighteen. Around the same time, he founded the Mo’ Wax label, which became synonymous with the coolest hip hop, electronic and alternative cuts (including DJ Shadow’s 1996 classic Endtroducing…, and records from Luke Vibert, Andrea Parker, DJ Krush and Attica Blues)—and it also showcased the visual talents of graphic artists like Swifty (who created the memorable graf-style label logo) and Futura 2000, whose designs also inspired clothing and toys by the label.

“I was intrigued about putting music into a different environment, how to make a record into an installation”

- Beyond the Road. Photo by Julian Abrams

Lavelle’s debut Unkle album, Psyence Fiction, came out on Mo’ Wax in 1998, and was created alongside Shadow (aka US sample maestro/producer Josh Davis)—who would later distance himself from the project (though he would briefly return in 2014, when Lavelle curated London’s Meltdown Festival); it also featured numerous indie star voices, including Thom Yorke and Richard Ashcroft. The highs and lows, bombast and rifts of Lavelle’s career are portrayed in Matthew Jones’s 2016 doc film, The Man from Mo’ Wax (tagline: “Rebel. Maverick. Pioneer”). Frequently, he has been lambasted as someone with ideas above his station: not a formally schooled musician or artist, but an unabashed enthusiast and obsessive collector—yet Lavelle is genuine in his passions, and his successful experiments have sparked a cultural alchemy, whether it’s Mo’ Wax’s golden era, his conviction about contemporary art (in 2002, he presented the first UK exhibition by cult sculptor/painter KAWS), or his fervour for international inspirations. The ambitious density of Unkle’s music has drawn various criticism, but it also provides the creative scope for BTR—and arguably, a blueprint for further “virtual albums” to come.

- Beyond the Road. Photo by Stephen Dobbie

Lavelle still looks street-casual in his mid-forties, and reels through his childhood fixations: “Greek mythology, Star Wars toys, martial arts… then hip hop was this culture that glued everything together.” He smiles, sheepishly: “I’ve never really felt that understood with what I’ve done creatively, especially with making records. There’s been a long history of having a finger pointed at me, like: ‘What do you do, and how does this work?’”

I’ve always liked that he seems unfazed by that. He laughs: “I’m very fazed, but I’ve just got used to navigating through it. It’s my journey; some of it is rewarding, some of it is incredibly frustrating, and you make mistakes… I have an interesting relationship with my home, because it hasn’t always been very kind to me. So, I’ve always travelled to different places and soaked up cultures where I’m not rooted in one scene. Somehow, the British are very good at expressing themselves in art and music, and that’s what I’ve taken from here, but a nationalist ideal is not something I’m interested in.”

“I’ve never really felt that understood with what I’ve done creatively, especially with making records”

Even the obsessive collecting (he apparently has “around 30,000 records” in storage), he insists, is about documenting history rather than materialism: “People just thought I was mad: ‘Why do you want to keep a Mo’ Wax flyer from Tokyo?’” Now, with artists like Virgil Abloh, the forefront will be archiving history before it’s even started. “I’m just massively into the idea of music and art connecting people: challenging them, but making them feel joy… feel something. You don’t always get everything right. But you try: to hear it, feel it and see it in a different way.”