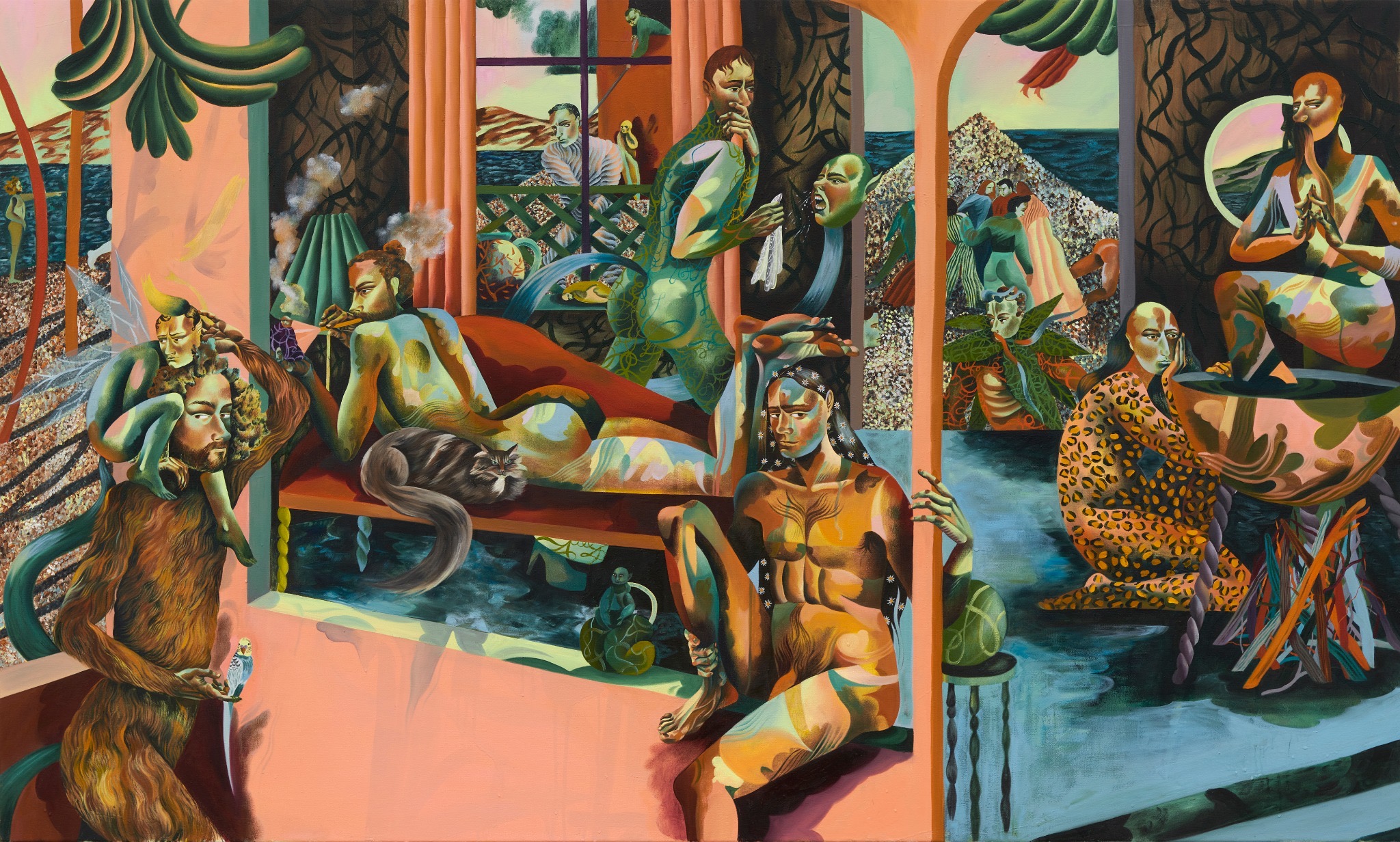

Jessie Makinson’s paintings straddle a fine line between perceived fantasy and reality, featuring sociable scenes flooded with lashings of vibrant colour and human subjects with elven ears, leopard print skin and garments made from giant leaves. Her works are lively and playful, evoking the wild abandon of a holiday, party, or alternate realm governed by leisure time, hunting and sensual eroticism.

“Ten years ago, it felt like you had to be really conceptual or really traditional, there was no middle ground”

The figures in Makinson’s works are lithe and bendy, stretching and folding around one another, or lounging casually on their own. Her compositions are complex, sometimes featuring a scene within a scene, or taking a flat, collage-like approach. While she is known for paintings of female and gender-ambiguous figures, she recently created an all-male painting for Victoria Miro’s digital exhibition I See You, which focused on female artists who paint male subjects. “People often say the women in my work look strong, independent and bored, and I wondered if the men would look the opposite,” she tells me.

Furry darkness, 2020 (above). My Fins Are Sleeping, 2019 (below). Courtesy the artist and Fabian Lang, Zurich

You recently showed a painting in Victoria Miro’s digital exhibition I See You, which included female artists who paint male subjects. Did you create Furry Darkness especially for the show, and how did it feel to focus purely on male forms?

I made the work specifically for the show. My figures have often been quite feminine, but I have recently been making them a bit more ambiguous, so I thought this was a good opportunity to do a painting with male subjects. I was interested to see what would happen. People often say the women in my work look strong, independent and bored, and I wondered if the men would look the opposite. In the end, I painted them in the same way that I approach painting women. They look like they’re in their own space, and there is a tenderness to them.

You often merge apparently contradictory elements. As well as the gender ambiguity that you explore, your scenes tend to swing between the fantastical and the everyday, and there is a mix of human forms and mythical creatures. Do you want your viewers to feel a sense of blurred reality?

I try to let the painting or story happen. I certainly leave room for the audience. I think that I often have ambiguous genders in the paintings, because when something creepy or sexual is happening, the element of power is different or removed. I like when you watch fantasy or sci-fi films and TV, and there are market or bar scenes. It always looks really shit, the same as our world but with some aliens in there. I’m really into the in-between action scenes in those kind of films, the everyday fantasy. Those scenes are always really rooted in the time that they’re made, like in Blade Runner or Star Wars.

Shadow Licker, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Fabian Lang, Zurich

What other sources do you go to for inspiration? There seem to be so many reference points, from mythology, to history, film and literature.

I read a lot, watch a lot, and collect images. The images I collect tend to be historical etchings or drawings rather than other paintings. I am interested in Dutch and Flemish brothel and inn scenes. People mention mythology to me a lot when they talk about my work, and I don’t actively look at it, but my paintings are sat in the visual realm of art history, most of which, if it was not religious painting, had mythological subject matter. As soon as you have women naked in the forest with a bow and arrow and something animal happening, it looks as though that’s what I’m referencing. I am interested in taking from seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century erotic drawings, often as a way to do figure arrangements, as the people in them are usually doing something really weird. The figures always look close and personal but they are in their own spaces at the same time.

- Tiniest Little Slice, 2020 (left); Downy Ruff, 2020 (right). Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York

I have read before that you start your works by painting shapes on the canvas and then create scenes around these. Is this still how you work? And are your detailed finishes, such as quilted fabric clothing and leopard print skin, introduced quite intuitively once you are painting?

I do this all over, underneath pattern and create shapes to begin with, but I will also have done some sketches, and have some found images, which all come together. The underpainting helps me place things. If I sit down and plan something completely there are no surprises; I can’t do something I wouldn’t normally do. So this underpainting helps with simple things like placing one thing under another, and with spatial arrangement. And it really informs the colour, which is why there is this patchwork feel to the works. But the details and pattern happen while I’m making the painting. The leopard print is a motif that solves a lot of problems. I am generally trying to get the figures clothed, and one way of doing that is to add leopard print or leaves to their skin.

“The images I collect tend to be historical etchings or drawings rather than other paintings”

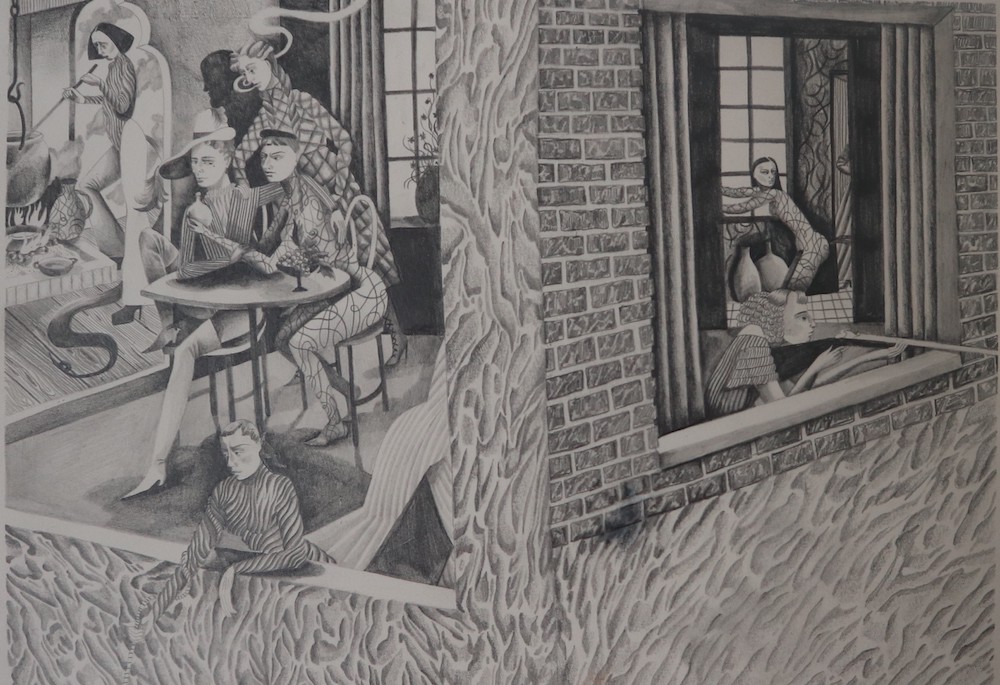

I’ve been looking at your drawings a lot recently. They are incredibly detailed. Do you like having paintings and drawings on the go at the same time, and do they inform one another?

I only started doing the pencil drawings in lockdown as I was trying to work out a way to do them that excited me. I realised that I could do so much in a drawing that I couldn’t do in a huge painting, and lockdown gave me the opportunity to try that. But they do take such a long time. I am working on a painting at the moment which is a section of a large drawing I did. Things have changed so much with drawing since I was studying. Ten years ago, it felt like you had to be really conceptual or really traditional, there was no middle ground. There weren’t many figurative artists around. I feel like Instagram has changed that quite a lot.