Jonathan Berger‘s An Introduction to Nameless Love is a sensitive project which centres relationships that function outside the romantic definition of love. It has seen the American artist chronicle the creative bond that existed between the Eameses; one of the last living Shaker’s connection with God; and the story of a doomed turtle who provided a US conservationist with meaningful direction in life.

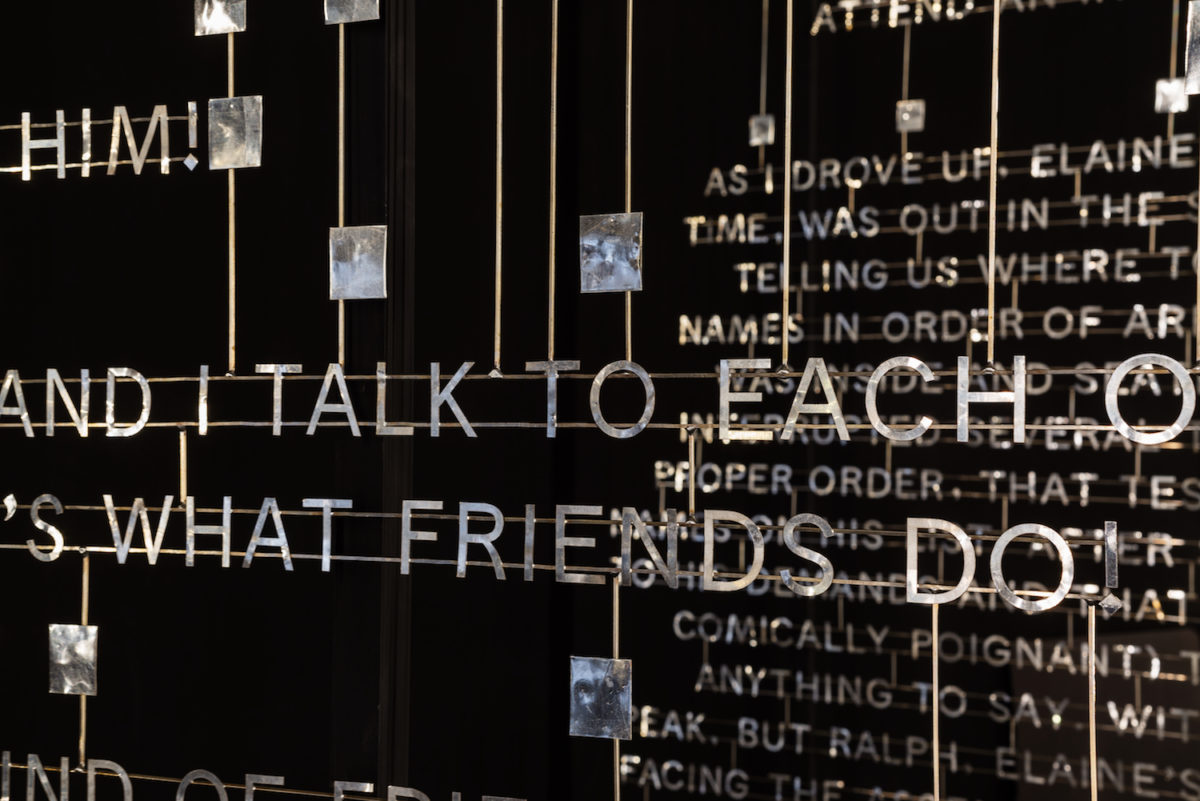

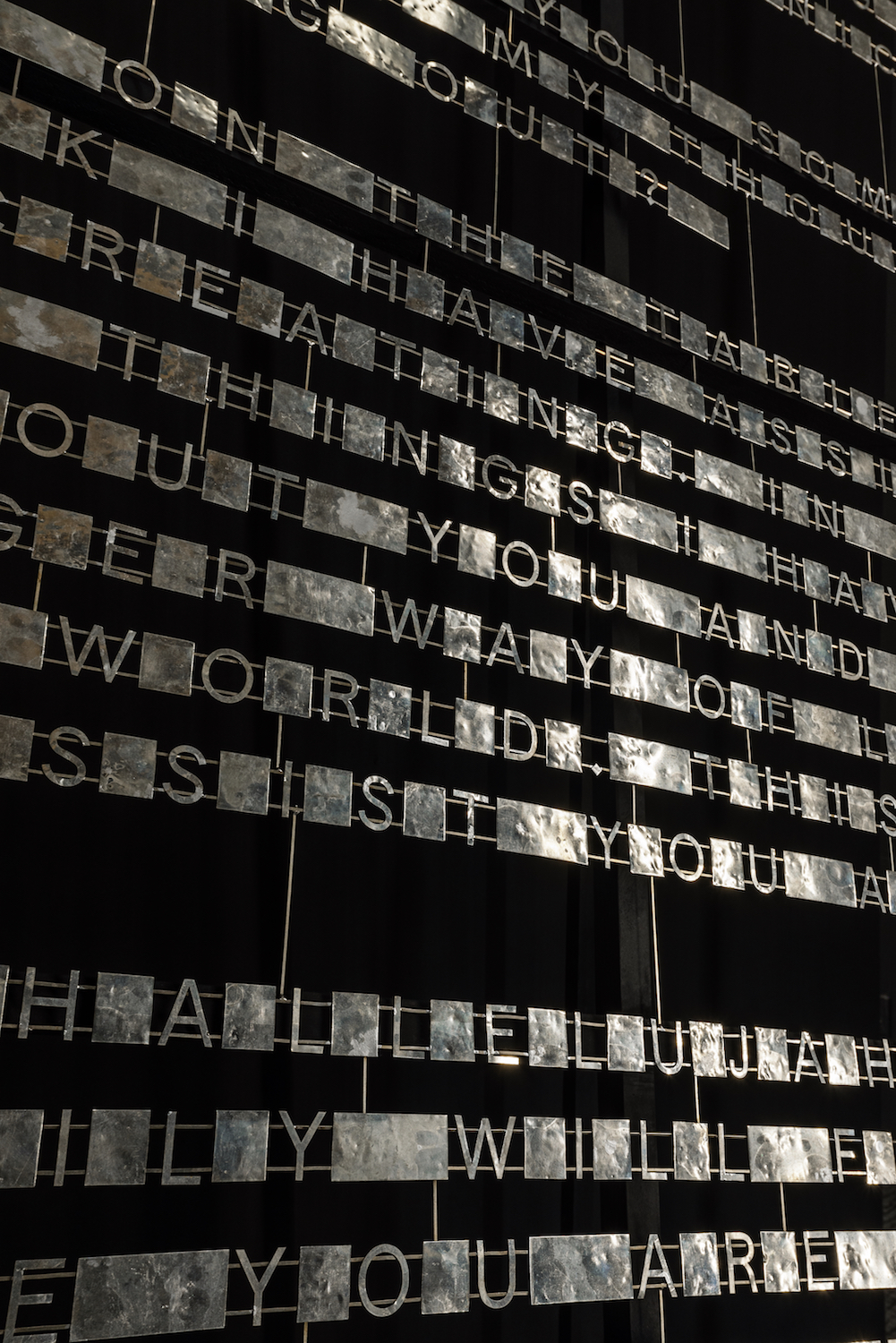

For this ongoing project, Berger explores each relationship in depth, often with the help of the subjects themselves or those close to them, and an editor. From these conversations he creates personal and moving texts, which incorporate everything from poetry to excerpts from books, historical documents and interview transcripts. These texts are then presented in the gallery space as a glittering constellation of tin letters. Each work tells the love story of a powerful fellowship, which has had a life-long impact on all involved. Later this week, the project will be shown at Participant Inc in New York.

- Untitled (from Behold the Elusive Night Parrot, by Mady Schutzman), 2019. Installation view at Participant Inc, New York. Photo by Carter Seddon

Through films, tv and the media, many people are taught from a young age that they must hunt for romance, and there is strong social pressure to lock someone down. The importance of friendships can get lost in the middle of all that. I’ve read that this project was inspired by your platonic connection with the late artist Ellen Cantor. What defined that relationship for you?

I had this five-year friendship with her. We became really close friends very quickly, and she died of cancer in 2013. I had sort of been her carer as well, and in the year after her death I just went into a place of mourning. I was trying to figure out why I had been affected in the way that I was. The friendship had many depths and elements that society normally defines as true romance: when you’re really being changed by someone. I never had that with anyone else, not a friend or a partner. There was something about the dynamic between us and who we were in each other’s lives that crossed into something else. I started thinking about it as a bigger question, and people get it. A lot of people understand that they’re more in love with their dog than their husband! The issue is, there is a societal structure which dictates what does and does not have value.

“A lot of people understand that they’re more in love with their dog than their husband!”

People want to label things and they want to understand and classify them. The bigger questions are: what is love and where do people find it? Who can have it? There is a side to the work that honours the human experience as unstable, as always in formation and trying to be understood. I think it’s about being in touch with how you move through the world, what is happening to you and what you do to others.

Do you use any guidelines to define the relationships you feature in your work? And how do you go about choosing the people involved?

I have recently shifted the focus from relationships formed strictly outside romance—which is what I was looking at when I started—to points of connection that aren’t traditionally romantic. Perhaps the most muddled version is Charles and Ray Eames, who had this marriage that quite publicly did not work. Yet they stayed together. They had a profound collaborative bond and a need to do these projects and fuel each other. What is interesting to me there is that the marriage changed; it started as one thing and then shifted into something else.

And how about the relationship between humans and animals? I see you have been working with a turtle conservationist, Richard Ogust.

It all started with this turtle he adopted out of a restaurant tank. He got the restaurant to sell it to him when he was eating dinner, and his relationship with that first turtle then spun out into this obsession and conviction to commit to wildlife preservation. He’s interesting because he is both empathetic and incredibly scientific. In that case, it’s about how an animal can change you and your life. His life’s purpose came out of this one initial relationship.

I am also working on a piece about two gay penguins (Roy and Silo, who are no longer alive) who cared for a rock as if it were an egg. I found the most interesting part of that whole story was the idea of the relationship between animals and inanimate objects. They were, in essence, insisting that this object was a living thing. I interviewed the zoo director and their handler, and the text is a radical edit from those two interviews. I am interested in moving around something in that prismatic way.

“There is a side to the work that honours the human experience as unstable, as always in formation and trying to be understood”

Once you have found a relationship you want to work with, what is your process? How much do you want to shape the text yourself?

The first thing I do is form relationships with people. It’s important that I’m not going in knowing what I want to get out of it, but just wanting to learn more. Once I’m in an exchange where it seems like it makes sense to work together, I usually do recorded interviews, which are then transcribed. I put together a micro ecosystem of me, the person whose story it is, sometimes there is someone else involved in the interviewing, and/or an editor I invite. We work together and boil down what is often a tremendous amount of transcript material into about 500 words. Then there is some process of going back and forth that yields the final text that goes into the show. The show itself is very aesthetically streamlined, which is also a very intentional choice. This continuity sits in friction with the shifts in story and language style, like a book.

- Untitled (Tina Beebe, Barbara Fahs Charles, Robert Staples, and Michael Wiener, with Matthew Brannon), 2019 (left). An Introduction to Nameless Love, installation view at Participant Inc, New York (right). Photos by Mark Waldhauser

How does the format of the works guide the viewer’s experience?

In order for you to read you also have to move around the work, because of the way the light reflects and the size of the pieces. So reading becomes a physical act. The other thing that’s crazy, which I truly did not see coming, is people read aloud. I’ve seen it about five times now and it’s really intense. I think part of the reason it has an impact is that it’s real. It’s not shaped within the constraints of contemporary art proper. It’s about me creating a vehicle to share these stories, and the people I’m working with can tell their story in a way that’s true to them.