A photographer who can make you feel as if you have watched an epic film distilled into in a single shot is rare, but Leigh Ledare somehow manages this in his work. He is known best for his series Pretend You’re Actually Alive, featuring his mother after she found a calling in later life to explore her sensual side via strip clubs and soft porn centrefolds.

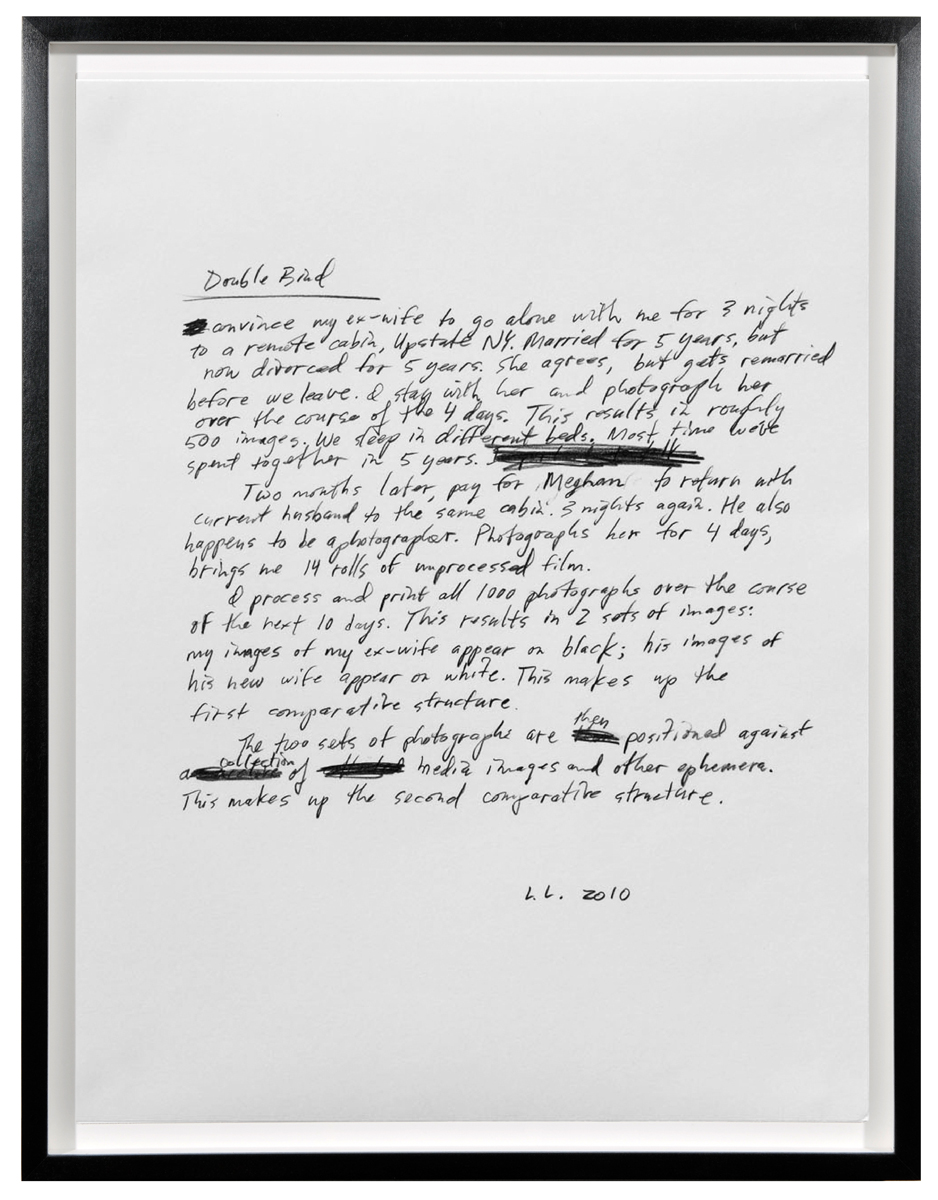

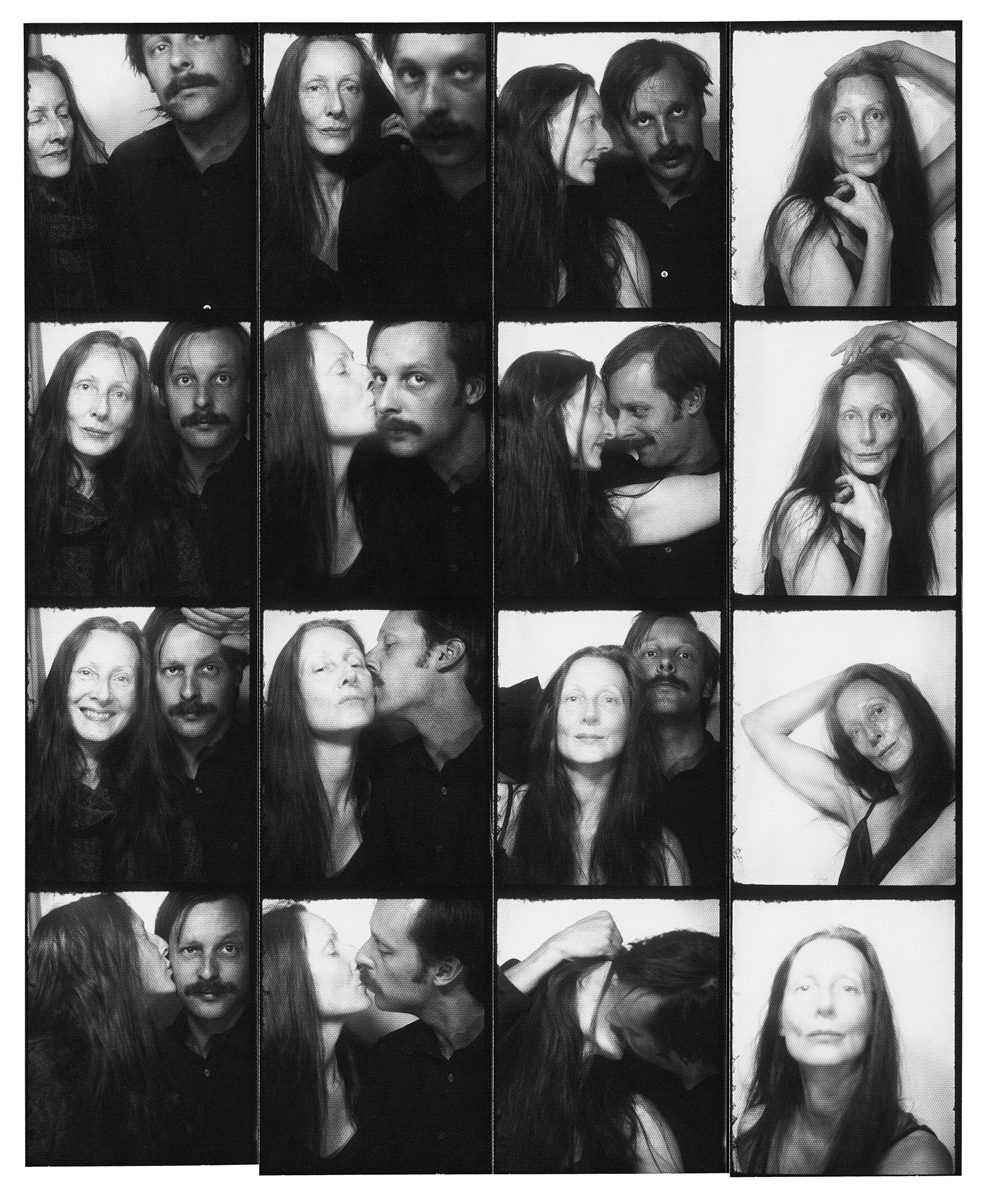

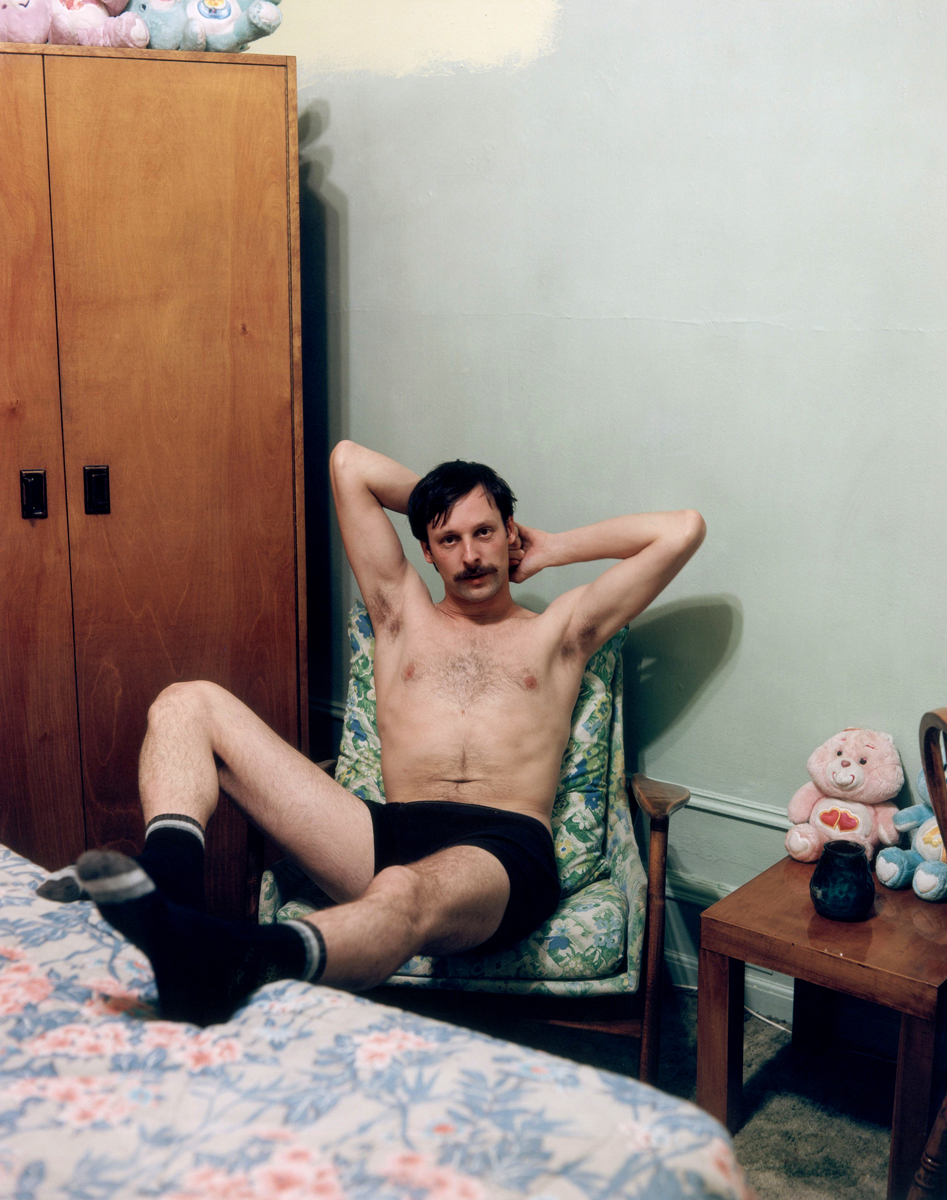

Unpacking the masculine, the sexual and the parental, Ledare then went on to create complex works with his ex-wife Meghan Ledare-Fedderly and her new husband, the photographer Adam Fedderly, in Double Bind. Ledare convinced her to join him for four days in a remote cabin in Upstate New York and made roughly 500 images; she repeated the trip two months later with Fedderly. The work generated two sets of images, which could be viewed in any number of binaries; a present and a past; an ex and a lover; all of which have no singular narrative, but why should they? Desire and the image have always been open to interpretation.

Your work is rooted in the act of image-making, although the more I examine it the less it seems to be about the images and the more it seems to be about the process, the game, the extraction, the act.

My projects revolve around emotional, material or social contracts. The content usually surfaces through observing some contradiction or ambivalence, something that gets caught under the skin. If it sticks long enough I inevitably start thinking “How can this be captured in a work.” At times this has stemmed from the personal—such as Pretend You’re Actually Alive, the work I made with my family, which circled around my mother’s complex performance of sexuality and negation.

“In a broader sense this project was caught up in American cultural expectations, and the disappointments that accompanied them”

I started photographing her when she was fifty-one, long past her career in ballet. She was dancing at a strip club instead, next door to her parents’ apartment. I was interested in how she was using her sexuality to find a benefactor and shield herself from her ageing, but also to rebuff expectations about how she should behave as a daughter, mother and woman of her age. Subjecting herself to these somewhat questionable situations allowed her to maintain an emotional upper hand within our family and, having been made complicit by her, I then mirrored her logic as a means of framing those dynamics. In a broader sense, this project was caught up in American cultural expectations, and the disappointments that accompanied them.

I mean this in relation to conformity, but also the residue of the culture wars of the sixties: logics of subversion and transgression, isolation as the downside to individualism, self-expression through consumption and a refusal in the US to deal with class difference.

It seems you use intimacy as a tool to lever ideas of the real and the staged. Could you ever see an image as something natural?

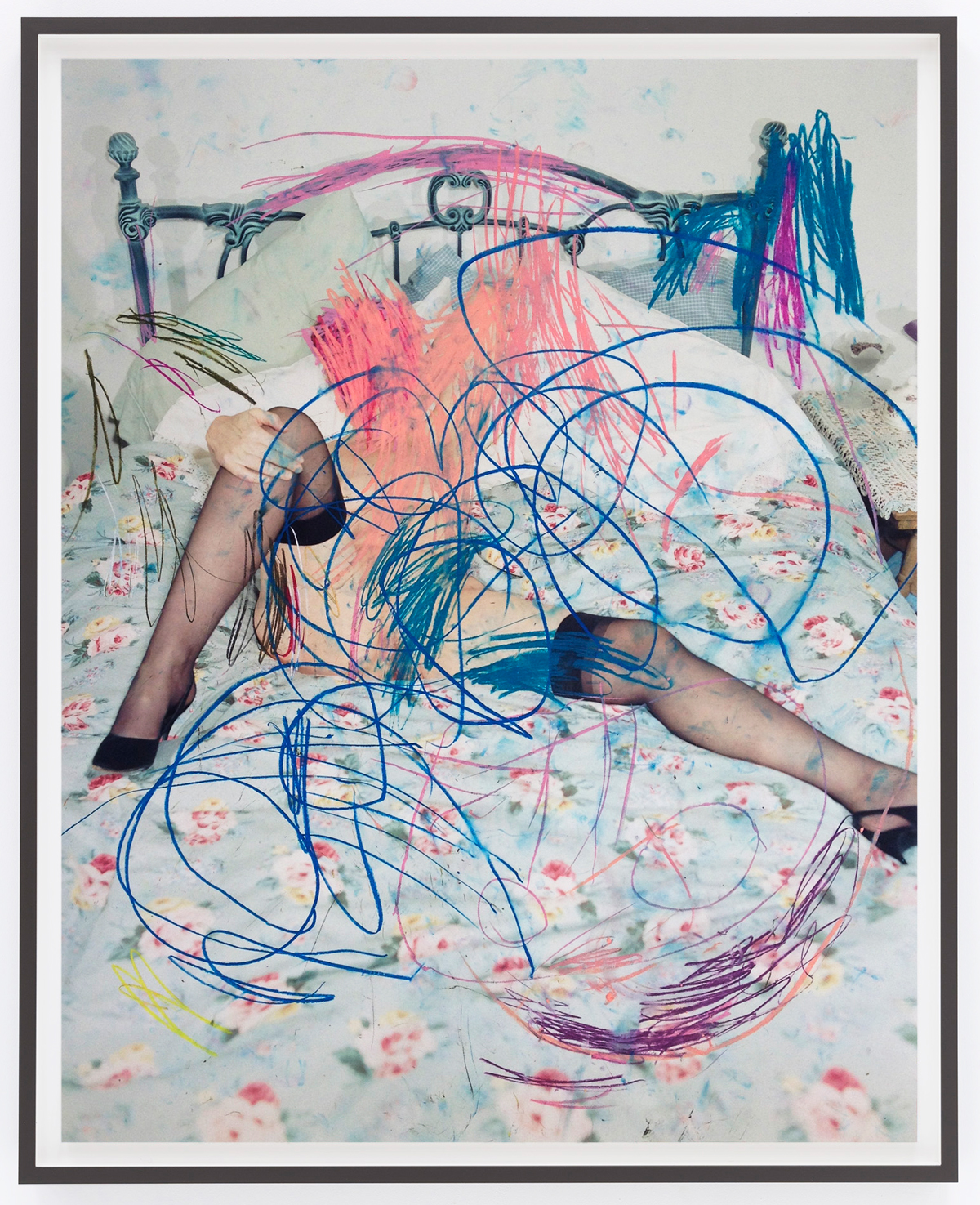

Perhaps the closest would be the interventions made in a series called Children’s Drawings. I started by printing an outtake from Pretend You’re Actually Alive, a photograph taken by me of my mother lying nude on top of a floral duvet, her legs spread. For each work I had a different three-year-old child draw in oil pastels directly over this photograph.

“Because my works are enactments, I always see them as opening onto some reality…”

The innocent marks of the child are mapped over an image that an adult viewer inevitably understands as pornographic; however, for the child, the body is a point of identification, related to one’s self and related to the mother. Mapped over each other, this pairing suggests that the development of sexual morality comprises a genealogy, that it’s something taught by society.

The child’s marks carry all sorts of associations—they are simultaneously gestures of self-expression and the markings of an omnipotence over the image; they transform my mother’s figure into an effigy and they act to censor, a fig leaf placed over something that shouldn’t be shown. Because my works are enactments, I always see them as opening onto some reality, some process or experience that has been undergone and which is real—which has real effects and consequences.

You speak of subversion and transgression and there is often a heavy erotic overture, you often seem to bring an idea of fantasy into the public sphere. As a viewer, I’m always wondering if it’s your fantasy or your subjects?

Well, I’d like to turn the question back around to ask how—as a viewer—the work stages your fantasies. Because the work plays off archetypes, in attuning one’s self to the work the viewer can’t help but activate their own identifications. As often as not this results in a projection of the viewer’s fantasies onto the participants or onto me. The fact is, these fantasies belong to the social—and that’s often the dilemma.

But who holds the dominant narrative when the work is in situ?

I’d almost characterize the dominant narrator as a system—one which is being occupied, from inside, in order to be sounded out. My work, which is inherently self-implicating, is interested in recognizing problems of observation and reproduction, not in trying to transcend them by pretending they aren’t there.

In that sentiment the question of authorship comes up. In a way you are the maker, but the work is also a product of the social or the relationship you ensue, right?

Well the works take up a networked or nested model of authorship that privileges the intersubjective and tries to understand how our agency works, and how who we are is a product of who—and what—we’re in relation to.

Can you give me an example?

Well, my first book Pretend You’re Actually Alive already laid this out, reproducing on its cover an unedited transcript of my mother discussing the photographer/model relationship, her agency and the lack of her being credited as an author in her previous work as a model. At times the work explicitly reveals this omission. At other moments, these hierarchies of authorship are intentionally posed as a provocation which the viewer has to sort. Double Bind is a good example too. Not only did I script the two trips, but after the photographs were taken I arranged the montages that comprise the final diptychs.

“We each hold distinct positions in the system, and our agency is a product of negotiating those positions”

I also created the schema for its presentation, where each set of images is positioned in conversation with the other, so that even though Adam and I are never pictured directly, we are—through my images appearing on a black background and his on white—present, and present relative to each other. This structure allows my agency to be readable against his, his against mine, hers against ours and so on. We each hold distinct positions in the system and our agency is a product of negotiating those positions.

What I find so unique about your work is the way you tackle narration, the setting, the desire and the social framework that seem unavoidable when reading the pieces. Without this, I wonder if it would be read as pornography or at least artful porn. It’s almost like the story is too good to be porn—after all, porn has always had terrible plots. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Bringing it back to social observation, I’ve found the anthropologist Michael Taussig’s notion of the “public secret” very helpful. He describes how within any society there are things that we collectively “know not to know”. This shared secret—that which is deemed unspeakable or taboo—actually comprises a highly charged form of social truth which, having been internalized by the entire group, functions as a means of regulating society. I find his observation profound.

In earlier counter-cultural readings of the pornographic, beyond eliciting desire, depictions of sexuality were seen as threatening a social order whose conformity expressed itself via the maintenance of repressive social and sexual norms. Pornography was transgressive. It was subversive. It was an attack on conservatism. Yet already by the mid-sixties, Taussig argued that consumerism risked de-sublimating the oppositional qualities of the counterculture, something which, in light of the Internet, has never seemed truer.

And how do you see it today?

Currently in the US the populous Right has appropriated the tactics of transgression and subversion previously associated with the radical Left. In her book Kill All Normies, Angela Nagle describes this as a new culture war, waged primarily through right-wing social media which, reactionary to the liberal agenda of the moral Left, has been harnessed to great effect.

The Left’s espoused tolerance towards anything but intolerance has been characterized by the Right as its own form of intolerance, a moral high ground around which they’ve orchestrated an extremely divisive, xenophobic, racialized and class-driven backlash. While a very different situation, in terms of effect, it strikes me that this mixture of shame/excitement in current politics, and the historical baggage that taps into, echoes ways the pornographic was called upon in an earlier moment to violate existing value systems.

So transgression comes in various shades?

My point is: I’m not as interested in what an image might depict, as I am in the complex ways we call on images to function. It’s crucial to have a holistic picture of this to be able to see the dynamics set in play.