Ice 4, 2018

Photo: James Wang

For her first solo exhibition in London, at Hauser & Wirth, Lorna Simpson has worked across three disciplines, utilizing collage, painting and sculpture to express notions of absurdity, fragmentation, precariousness and both psychic and physical tension. The work is predominantly new, made within the last eighteen months, and signifies Simpson’s continued dedication to the intersection of gender, identity and history. Her work is evolving and often process-based. “It’s not about having the security that it will all fit together, or be ‘successful’,” she explains. “The idea propounds the work. It’s about the fulfilment of surprises, and everything coming together. I give it my best and see what happens.”

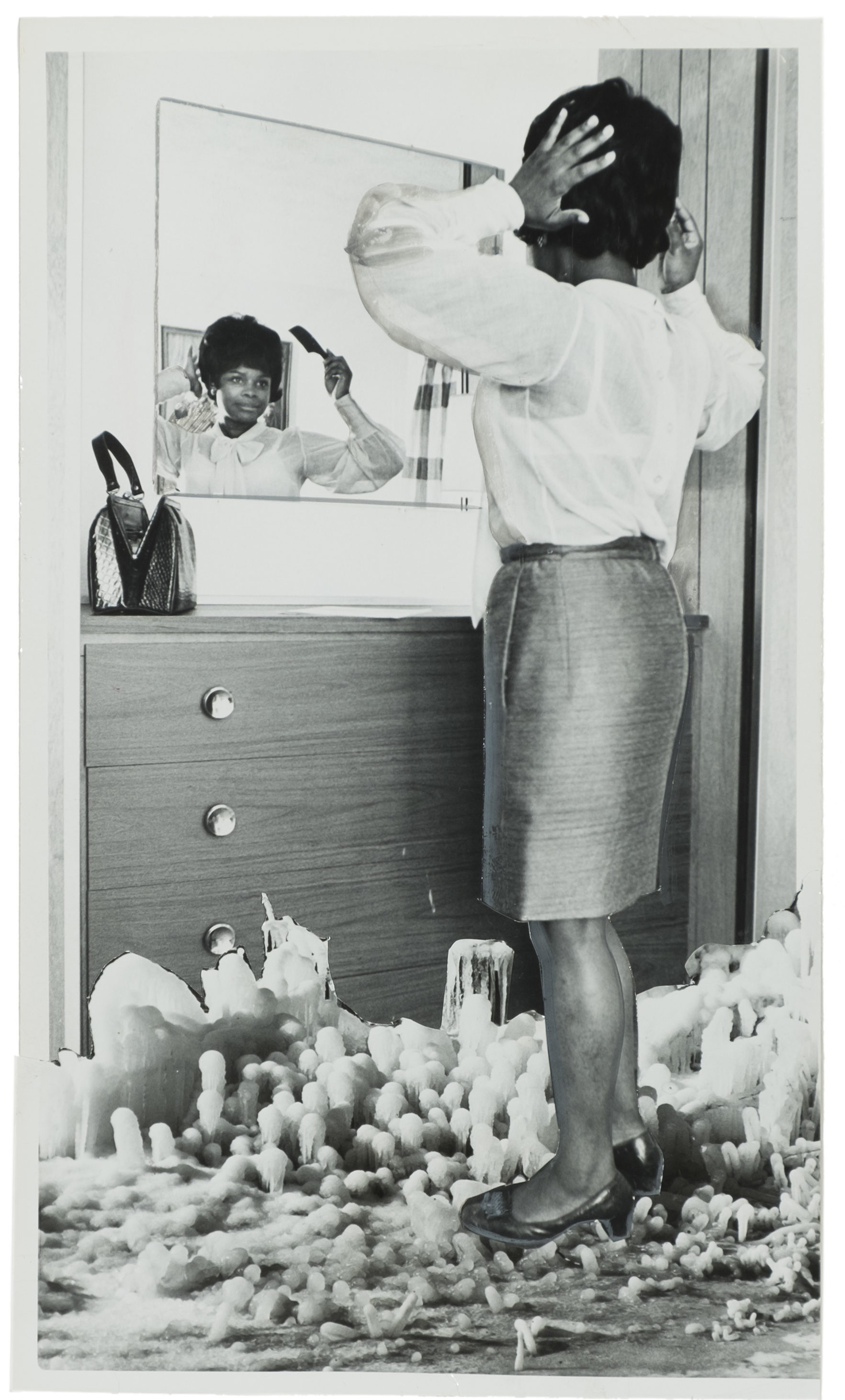

The exhibition opens with a wall of forty photographic collages, all grouped under the title Unanswerable and configured from Simpson’s collection of material from magazines or archival photography sourced from defunct newspapers. Since the beginning of her career Simpson has often employed collage and the juxtaposition of found images as a means to respond to contemporary culture, with female protagonists

taking centre stage. The representation of women in advertising and editorial provide her with ample material to tease out the relationship between the female form, psyche and identity.

Photo: James Wang

The narratives that Simpson has set up are surreal and strange. Women appear calm and collected, despite sitting on thrones made from ice blocks or bursting into flames. Many of them wear armour or have large feathery wings. Although, it seems that some of the images that Simpson selected were absurd before she began working with them. For example, there is a focus on the domestication of wild animals. In one collage she uses an image of a deer that appears to be doing the washing up.

“We’re fragmented not only in terms of how society regulates our bodies but in the way that we think about ourselves.”

“I’m constantly making these collages, I make them regardless of what I’m working on,” Simpson says. “They provide source material in terms of ideas, often influencing the paintings. But they are also works in their own right.” The following night, while in conversation with Thelma Golden [long-time friend and director of the Studio Museum Harlem], she discusses the synchronicity between her use of other existing images and the making of new ones, “I use my work as my own ‘bible’ to refer to.” This artistic tendency is made explicit with her large sculpture Woman on Snowball, which is based on one of the collages from Unanswerable.

A small female figure, made from composite images, sits atop a large snowball. The collage became an architectural model, in order for the sculpture to be designed exactly to scale. The contrast of a small body with a giant snowball conveys a sense of precariousness and the weight of expectation. Akin to the phrase “to snowball”, there is an element of momentum, of gathering force. “She can’t stay there forever,” Simpson notes.

Woman on Snowball. Installation view, Unanswerable, Hauser & Wirth London, 2018

Photo: Alex Delfanne

The ink and acrylic painting Montage embodies the same sense of physical and psychological danger, which runs throughout the show. Composed of five spliced panels––akin to a filmstrip or freeze frames––a figure is depicted reclining in bed, teetering on a window ledge and captured in the act of jumping or falling. “The notion of fragmentation, especially of the body, is prevalent in our culture,” Simpson explains. “We’re fragmented not only in terms of how society regulates our bodies but in the way that we think about ourselves.” Golden perceived the work as a “tumultuous dream”, the sense of conflict, tension and unease conveying the undertones of life in America.

“These magazines are the primary bible for black imagery. The writing was unapologetic. It was about representing the fullness of a black world.”

The majority of Simpson’s images are mined from her collection of vintage Ebony and Jet magazines from the fifties to the seventies. “They informed my sense of thinking about being black in America and are both a reminder of my childhood and a lens through which to see the past fifty years of history.” In conversation, Golden and Simpson explore the significance of the publications in relation to notions of the archive, black cultural manifestations and the history of representation. “These magazines are the primary bible for black imagery. The writing was unapologetic. It was about representing the fullness of a black world.”

Photo: Alex Delfanne

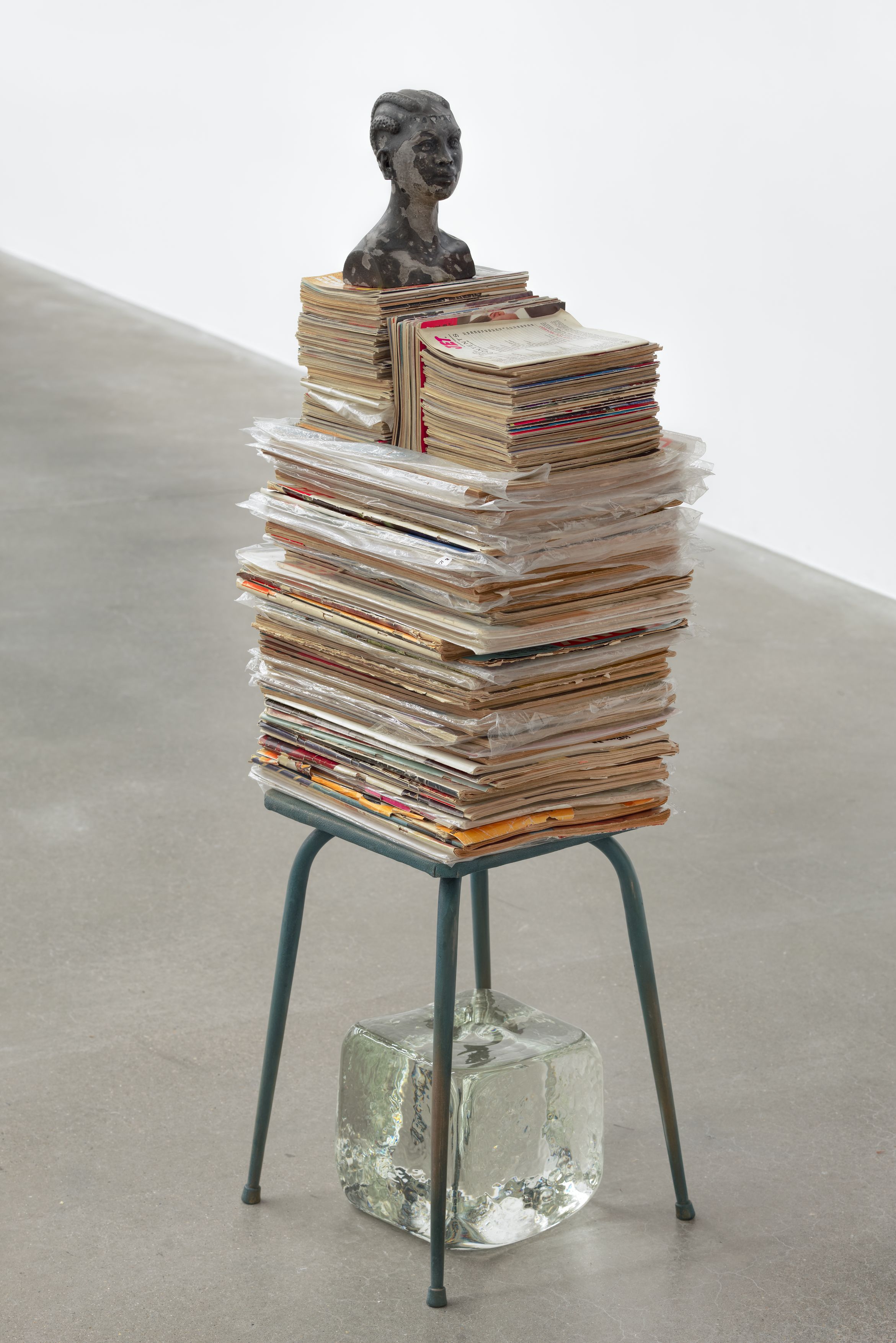

In 5 Properties and 12 Stacks, copies of Ebony and Jet are stacked up and arranged. Glass sculptures weigh down the magazines, their slumped, free-form liquidity functioning as prisms and lenses, obfuscating the print imagery. “There’s something about ice that has come into the work that indicates either freezing or endurance,” Simpson remarks. “In America today there has been an onslaught of a return to a past that is dying out.” The suspended state of water indicates the suspended state of history.

Ice 5, 2018

Photo: James Wang

Throughout Simpson’s multiple, large-scale Ice paintings, dark foreboding landscapes are evoked, merging geological ice formations and glaciers with volcanic eruptions. Appropriated imagery from the Associated Press and other sources are collaged and then covered in painterly washes of saturated ink. These canvases are then added to, with other smaller cuttings or montages from newsprint or magazine imagery. The colour scheme is disciplined, limited to black, grey and acid blue. Like the ice, the inhospitable and dangerous landscape is another cutting remark about the political situation in America. “What happens when hell freezes over?” she laughs.

All images © Lorna Simpson, courtesy Hauser & Wirth