As autumn chills swiftly approach, there’s plenty of time to scroll mindlessly through old holiday selfies and lament ever-fading tan lines, but your time could be better spent flicking through a gorgeous new book that chronicles poolside photos from throughout history. The Swimming Pool in Photography examines the phenomenon of these manmade bodies of water, from early facilities designed for “bathing” (the emphasis being on cleansing as opposed to exercise) to the glitzy offerings of luxury hotels and private dwellings.

Although this title focuses heavily on aspirational visions of perfectly curved modernist diving boards and heavily tinted shots of grinning poolside pageantry, it is also keen to point out the important sociopolitical history behind pools. In the opening essay Francis Hodgson states that “the swimming pool has been at different times and places suburban, exotic, utterly private, boisterously public, a threat or a blessing.”

He references the establishment of public baths in Victorian England (where previously the poor had no means of washing) and the history of racial segregation in the US (where pools continue to be something of a battleground even in 2018) including the startling fact that, following the decision by African-American Freedom Riders Kwame Leo Lillard and Matthew Walker Jr to swim in a pool in Nashville in the summer of 1961, every public facility in the city closed for four years.

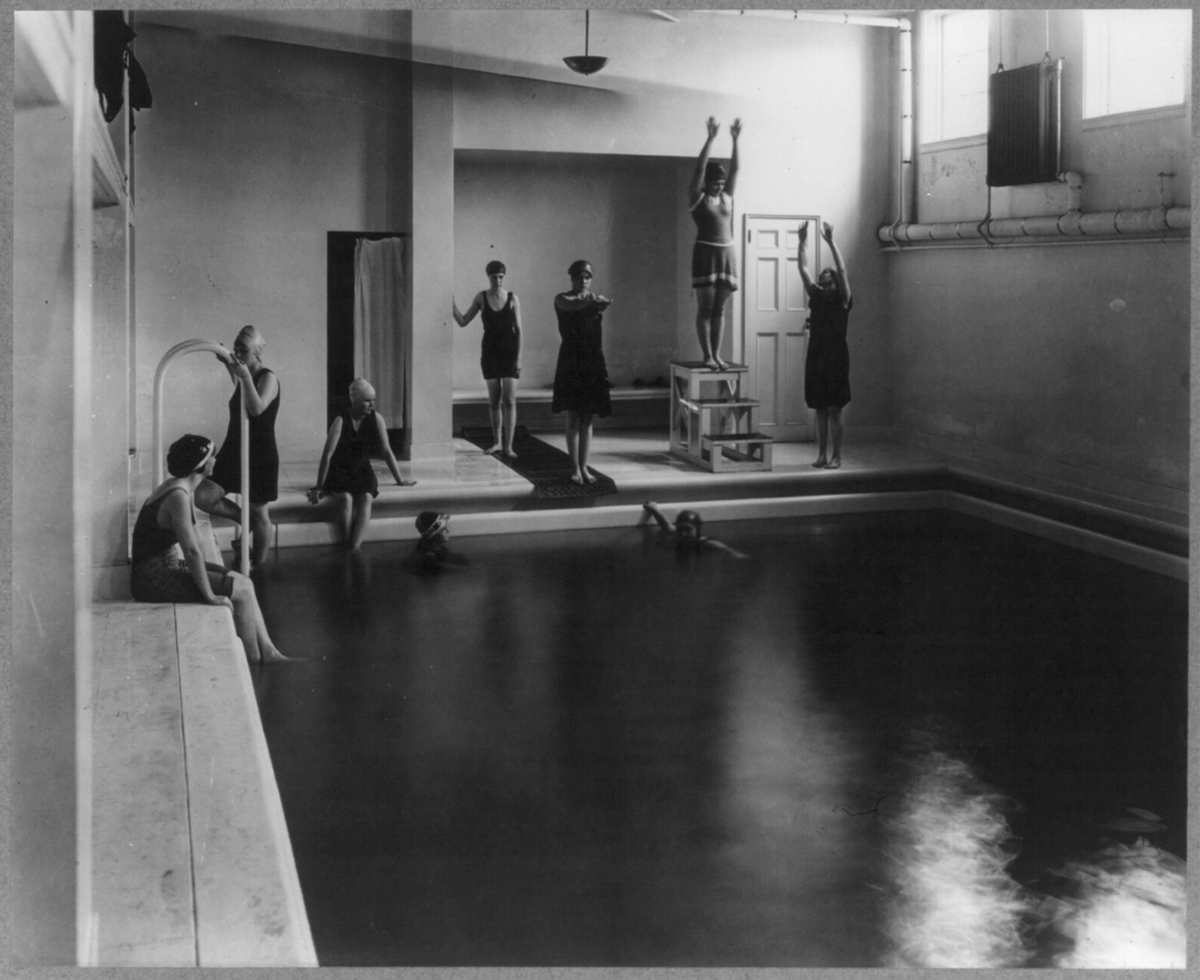

Above: Washington, D.C. Mount Vernon Seminary. Girls in swimming pool, 1864-1952 © Library of Congress. Below: Rooftop Pool at Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse © Pixabay

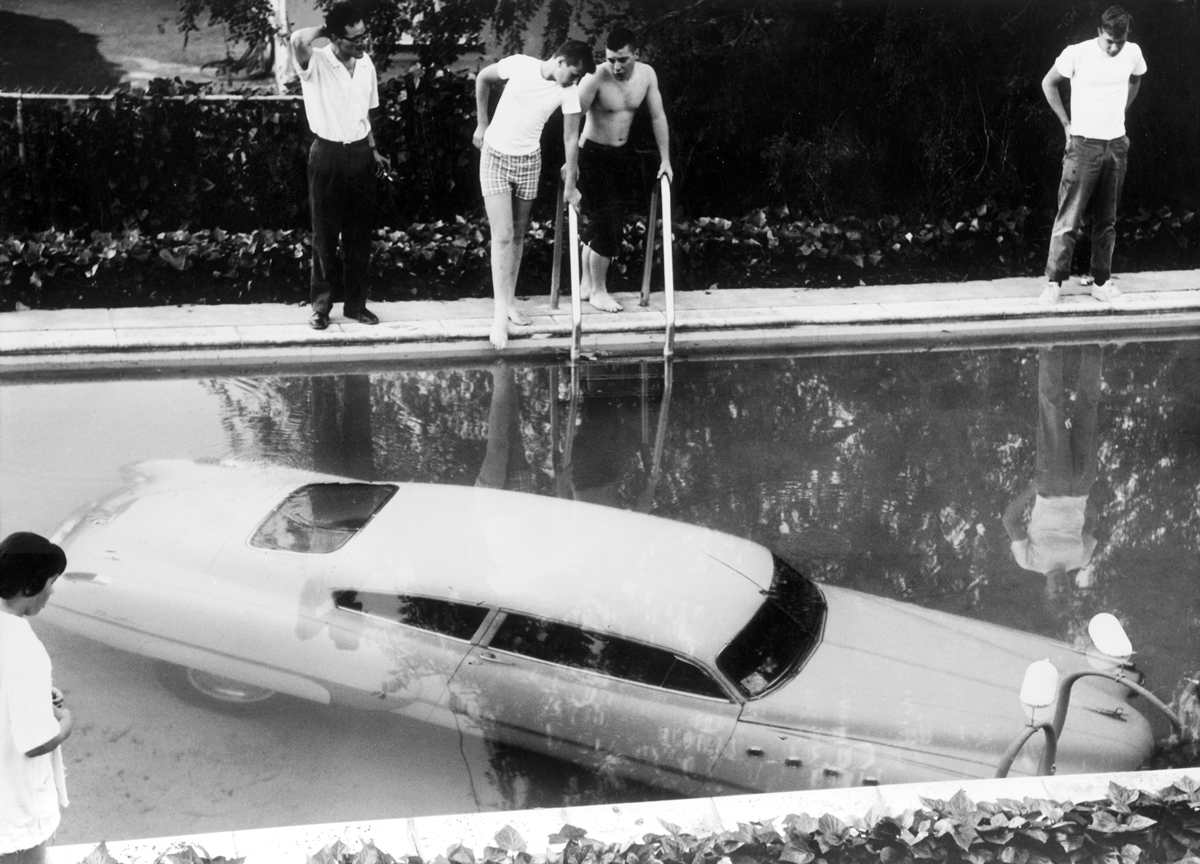

Sadly there are no photos documenting these forms of activism in this book (perhaps few exist), but there are some extremely sombre images of abandoned or devastated locations in Liberia, Afghanistan and various cities in the UK. These drained voids seem to represent something particularly unsettling, as their state is the very antithesis of what they were designed for. It is telling that these shots serve as something of an epilogue to the wildly jubilant photos that come before.

All in all, most of these images are joyous aesthetic marvels. Alex MacLean’s bird’s-eye views of Floridian hotel pools form their own wild jigsaw puddles, while other vacant bodies of water become an extension of cutting-edge architecture, such as Le Corbusier

’s rooftop venture (which in reality is more of a children’s paddling pool).

This book also spends plenty of time focusing on the multifaceted human activities that take place in and beside the pool. Black-and-white shots of men and women gracefully plunging into the water are shown along with huge crowds jostling for space in theme parks and pleasure towns (one of Martin Parr’s favourite subjects). A mother and child brace the thrill of a dip surrounded by snow in Colorado, and there are plenty of examples of swimsuit models lining up by the water’s edge and posing, lest we forget that swimming and its acquired attire has often called into question issues of gender equality and misplaced concerns around morality.

Allan Grant’s particularly camp portrait of Jayne Mansfield sporting a fluffy bikini and surrounded by floating bottles moulded in her own image is probably one of the most ostentatious and impractical images to grace these pages. Ultimately, it is the most accurate portrayal of the unadulterated (and Instagram friendly) fantasies that so many of us dream of when we imagine ourselves by the pool.