If you’ve found yourself having more casual conversations about murder lately, you’re not alone. The past couple of years have seen a true-crime boom. Murder podcasts regularly top the iTunes charts; Netflix promotes in-depth dives into the minds of serial killers as “bingeable”; and those of us with one eye on ethics are having to write op-eds telling people off for romanticizing Ted Bundy. Murderers, especially serial killers, often regard themselves as geniuses, as “artists”—perhaps that’s because society is so fascinated with the warped minds behind some of the grimmer crimes. But what’s the view from the other side of that metaphor? How does art feel about murder?

The connection between the two goes way back. Shortly after The Ratcliff Highway murders—the first true-crime sensation—swept across British breakfast tables in 1811, Thomas de Quincey wrote (in high irony) “As the inventor of murder, and the father of the art, Cain [of Cain and Abel, Adam & Eve’s sons from the Book of Genesis] must have been a man of first-rate genius.” The philosophical mess he was mocking hasn’t grown less entangled. The foundations on which the comparison is built are, however, under increasingly hostile scrutiny these days, in both the art and true-crime worlds. When art which tackling real-life murder is involved, that scrutiny can intensify to the point of combustion. Just ask Dana Schutz.

“Murderers, especially serial killers, often regard themselves as geniuses, as ‘artists’”

So where can you direct your gaze when contemplating the abyss? Towards the victim? Pierre et Gilles’s Le Dahlia Noir + January 15, 1947 (2003) pushes the murder-as-pop-spectacle problem to the limit, leaving you with an emptied-out feeling of having seen something you normally try to avoid acknowledging. Leaning in gleefully to the noir-tinged glamorization of the infamous Black Dahlia murder, they play with the media’s sexualization of victim Elizabeth Short by casting retro-femme burlesque queen Dita von Teese and burying her dismembered body in the literal tinsel of tinsel-town. The painting reveals how much her personhood has been erased by her iconic victimhood, but at the same time participates more than a little in that objectification.

What about looking at the criminal? There’s something almost obscene about Juergen Teller’s portrait of American football star turned double murderer OJ Simpson. The disturbingly conspiratorial air of the work is practically a signature of Teller’s style; he’s famous for achieving a shocking intimacy with his celebrity subjects. His choice to photograph Simpson is morally grey; he has so much cultural cache that the portrait can’t help but contribute to his subject’s rarefication, but at the same time it’s the cache we gave Simpson which brought him into the photographer’s orbit in the first place.

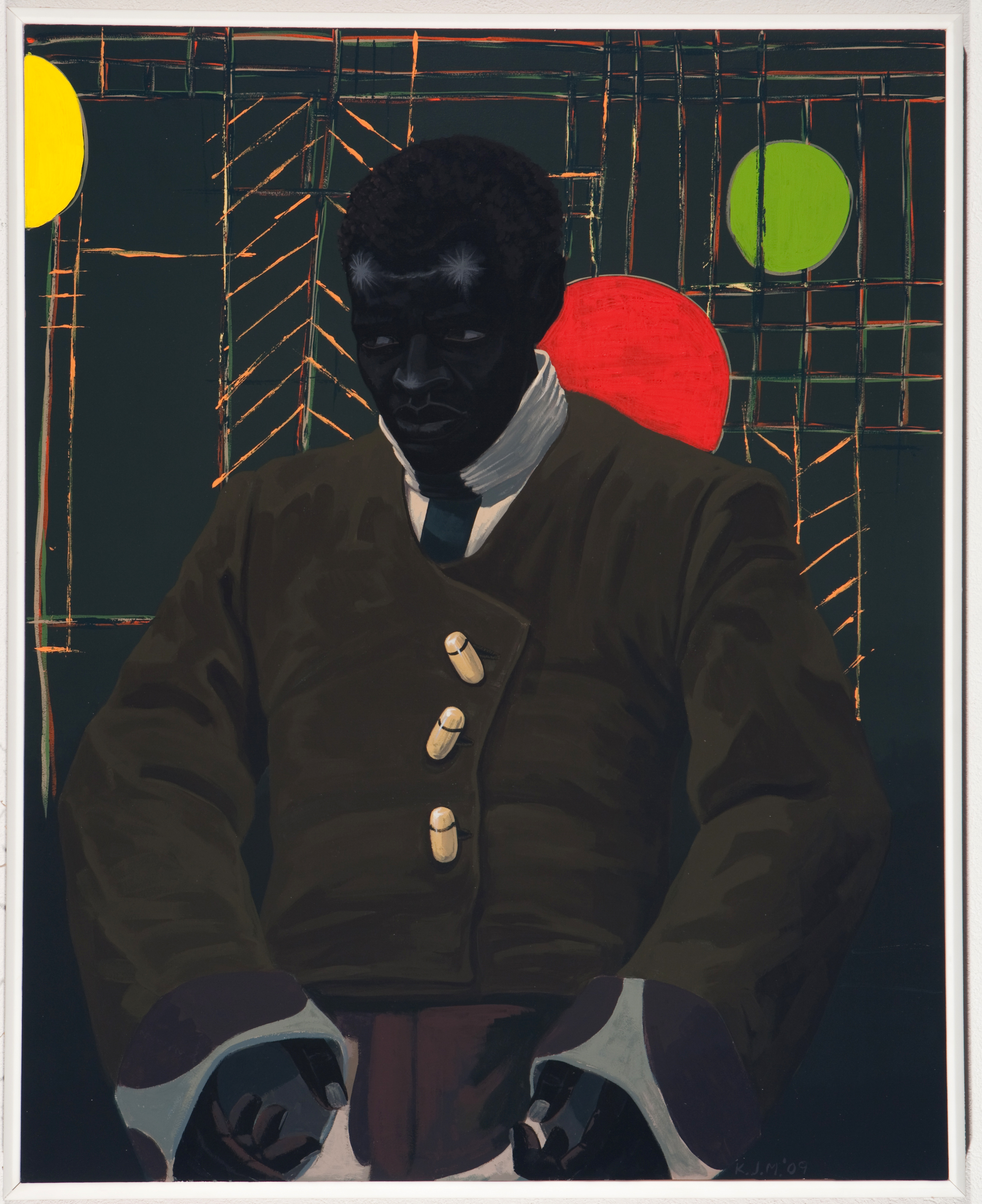

Kerry James Marshall’s The Actor Hezekiah Washington as Julian Carlton Taliesen Murderer of Frank Lloyd Wright Family (2009) is more thoughtful, highlighting the social facets of the mystery. The man’s motives were never ascertained, but there’s a strong whiff of intergenerational racial trauma about the circumstances. Casting an actor and staging an old-fashioned portrait, Marshall focuses on the story and encourages a more “literary” analysis. Marshall does not sensationalize, merely quietly speculates on the dynamics, both psychological and social, which led to the murder, capturing the objective violence of the crime in the moodiness of the painting.

“Caravaggio killed people, and he’s hanging in the Louvre”

Other artists prefer interrogating witnesses to psychological profiling. Jordan Wolfson

frequently requires his viewer to see something they really don’t want to. His 2017 VR installation Real Violence forced anyone who put on the headset to watch a violent attack in which the artist beats another man “to death”. Participating is a gut-wrenchingly complicated choice; all you’re seeing is violence, which you’d look away from in almost any other context—movies and gaming are another matter. He shows us how easy it is to make exceptions for art and artists. Wolfson is, by his own admission, not really a moralist—the tone of his work is more often “Look what I made you do, look what I made you see.”

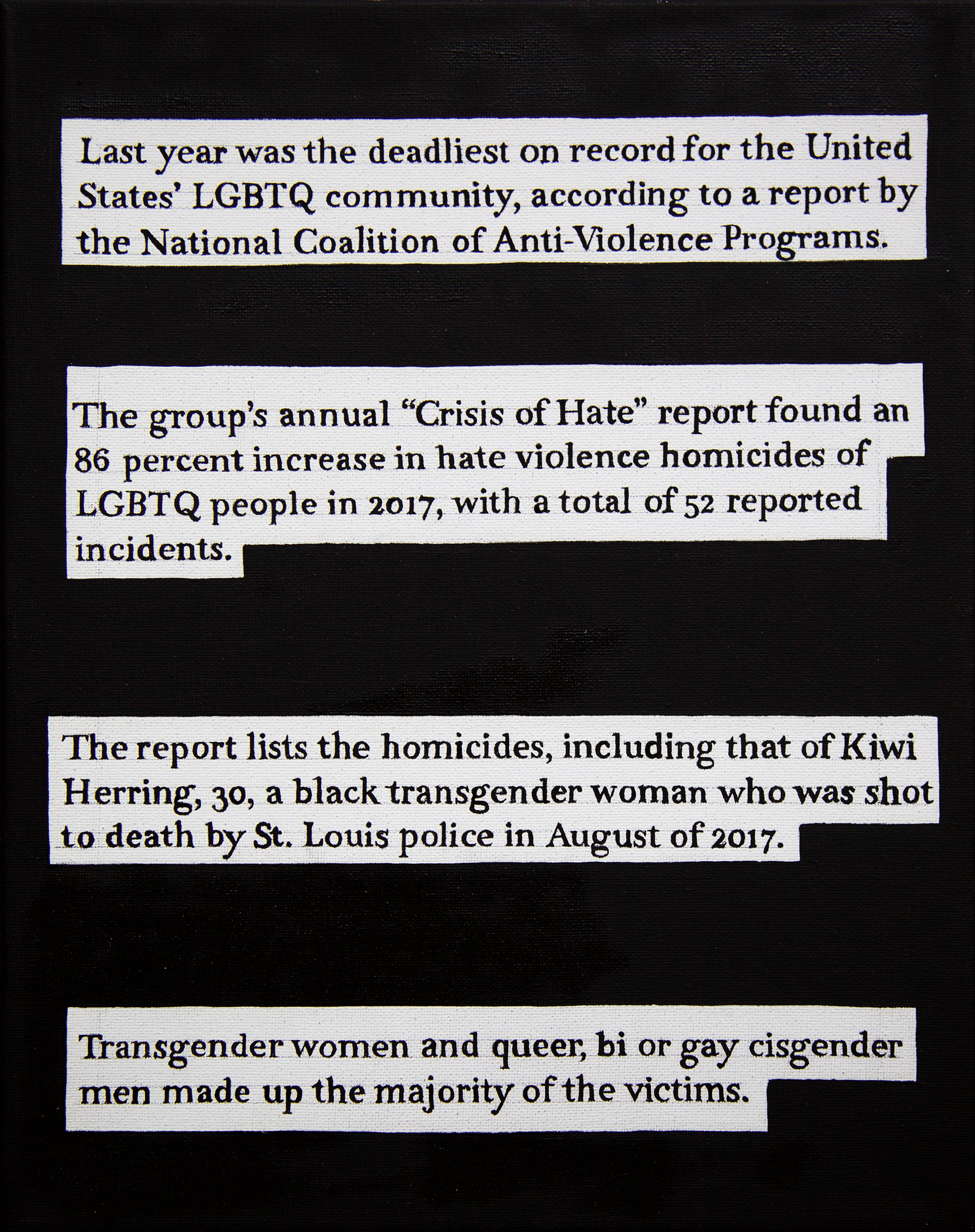

If that sounds slightly like the perverse delight of a serial killer staging a scene, Mike Kelley might agree with you. Pay for Your Pleasure (1988) held a mirror up to male artists participating in the same fiction of being the “exception to the rule” as murderers. In the work, portraits of key historical thinkers, alongside quotations linking art and crime, line a hallway. In one such pairing, we learn that according to Oscar Wilde “the fact of a man’s being a poisoner is nothing against his prose”. Wilde is an exemplary conundrum; by the standards of his day he was a criminal, and it is certainly nothing against either his prose or his poetry, but murder is more than just a metaphor for crime. (McDermott and McGough’s Oscar Wilde Temple includes works documenting LGBTQ+ homicides, gently undermining the playwright’s hyperbole even as it honours him.) When Kelley’s work was shown in Chicago, at the end of Kelley’s hallway was one of infamous serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s (dreadful) paintings, alongside a box for donations to victim’s rights groups. Look, Kelley says, he thinks he’s an artist too.

So what if Gacy’s paintings were good? Caravaggio killed people, and he’s hanging in the Louvre. Many of our ideas about art still rest on the idea of a genius who can, and should, rupture our reality. “The simplest surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly into the crowd.” We don’t know of anybody who acted on Andre Breton’s suggestion directly—but what if they had?

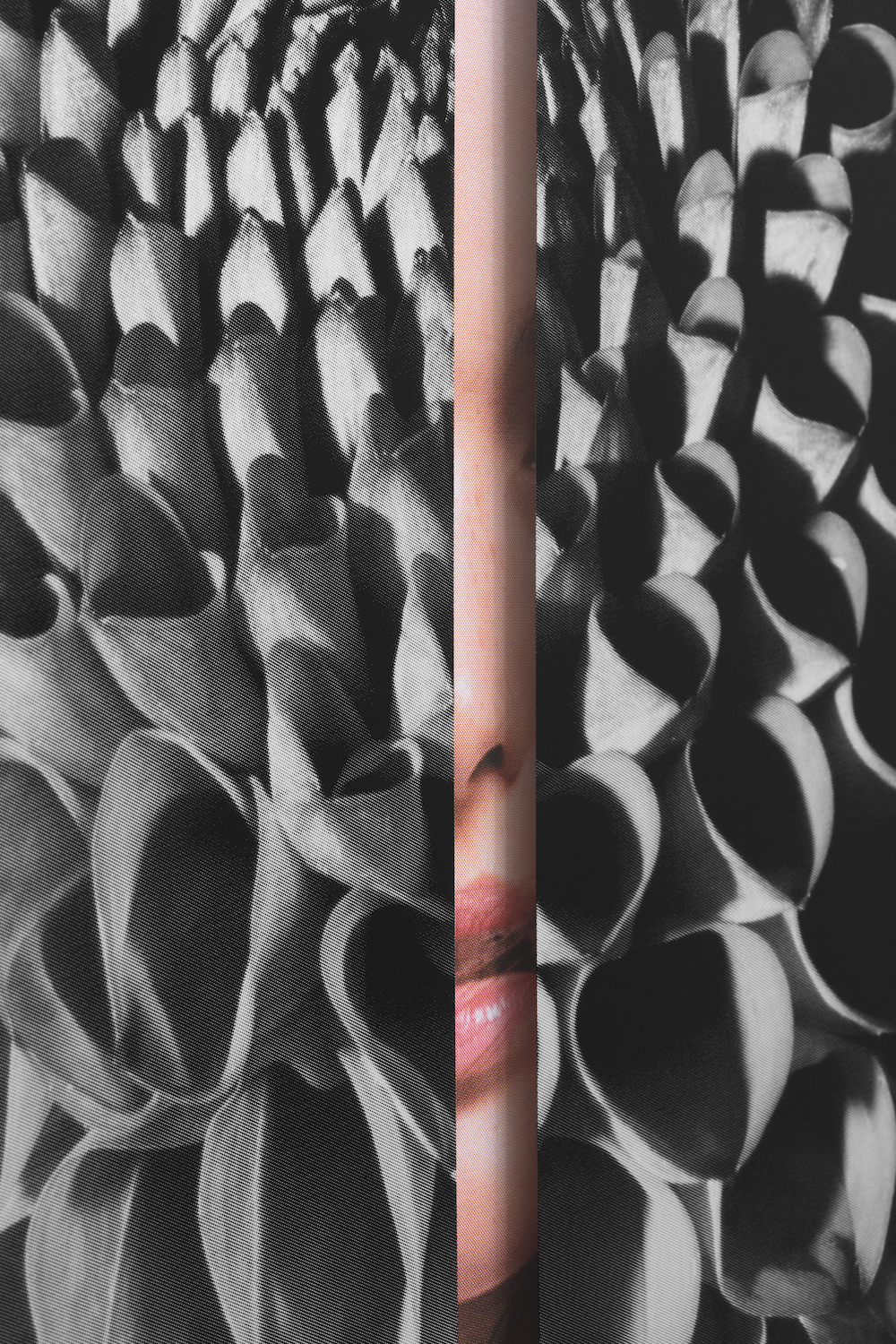

Perhaps the ethical conversation in the newly invigorated true-crime debate will help disentangle this messy, unhelpful intrigue over “geniuses”. Kathryn Andrews’s Hollywood Dahlia series (2019), deliberately focuses on the damage done to femininity by the long tradition of (unironically) “considering murder as one of the fine arts”, tackling the Elizabeth Short case without giving the unknown murderer the satisfaction of marvelling at his work. Andrews focuses on the victim, almost totally obscured by the sinister black dahlia—the moniker smothering her, even in death—pointedly re-enacting what both the murderer and society did to this human being. It feels like a step in the right direction.