It was as if the last few weeks of blistering, rallying cries had fallen on deaf ears. As if the protests and the posts amounted to nothing. On 7 June, Black Lives Matter protestors finally toppled the 1895 Grade II-listed John Cassidy statue of Edward Colston that had occupied The Centre in Bristol for more than a century, despite calls for its removal that had spanned decades.

A few weeks later I stood in front of the empty plinth in Bristol, a city I spent a lot of time in as a child, wondering what might take up that place. Artists like Turner-prize winner Lubaina Himid and John Akomfrah have brought Bristol’s specific role in the Atlantic slave trade to light in major solo exhibitions in the city in recent years. Perhaps, I thought, they might be the ones to give a new shape to the heart of this city that could better reflect its community.

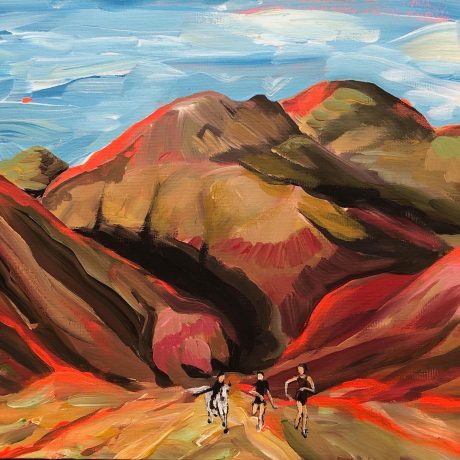

On 15 July the possibility of that place was violated. YBA Marc Quinn, a white artist who lives in London, took it upon himself to be the person to occupy that space. According to reports, Quinn was shown a photograph in the newspaper of Jen Reid, the BLM protestor who stood on the empty plinth after the statue was felled, and decided to make a sculpture in her likeness. The sculpture is titled A Surge of Power (Jen Reid). Reid is, interestingly, credited only in parenthesis, despite her apparent collaboration in the whole process.

The words of the title are taken from her own description of feeling an electrical current coursing through her when she stood on the empty plinth during the historic protest and raised a fist in a Black Power salute. It is a gesture that beckoned to the “enslaved people who died at the hands of Colston”, Reid said, as much as to her own family and future. The statue was installed in stealth and without consent in the early hours, by a team employed by Quinn; the steel and resin work and its erection was paid for by the artist himself.

“This is how you continue to prove that history is always, emphatically, written by white men”

“THIS is how you make history!” Countless articles and social media posts were quick to clamour in praise of Quinn’s performance, many of which were shared by the artist to his professional Instagram account with pride. Yes, I thought, this is exactly how you make history, and how you repeat it. This is how you continue to prove that history is always, emphatically, written by white men. Because it is they who wield the power to create history. They are the ones who have the financial means to make a sculpture and install it in a public area, without permission, and without fear of reprimand. People who, despite being removed and detached, lacking in knowledge and research, feel free to make grand public gestures on the subject.

Marc Quinn has never focused on themes of racism, colonialism and black history in Britain. To me, his work has always represented the glibness of contemporary culture and its vacant, self-serving gestures. He has made sculptures about experiences that weren’t his own—notably his marble sculpture of a pregnant Alison Lapper, displayed on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square from 2005 to 2007—that presumably he profited from, and continues to. Similarly, he stands to gain considerably more than his latest subject Jen Reid from the sculpture and its subsequent attention.

I go to Quinn’s Instagram page to ask how much Jen Reid was paid for her participation in his sculpture. He has turned off the comments. All that remains under his posts about the performance is the praise. “Well done Marc, you caught the moment”; “You deserve the success that follow [sic]”. In an IGTV post Quinn shared on his account, he stated how “the horrific death of George Lloyd” had brought Black Lives Matter to the public consciousness—seven years after the movement began.

The initial response from the press and from some of the most prominent figures in the British art world was overwhelmingly positive, given that the sculpture focused on a black woman in a position of power. But while that narrative holds true, there is a more insidious and nefarious system at play here. And yet again, it was up to black artists to raise critical voices on their own social media accounts, as if this is now part of the practice of every black artist.

Among the first was a number of searing video posts by Larry Achiampong, who called out the way the anti-racist movement is being treated like a “fucking festival”. The visceral pain, anger and exhaustion are palpable, leaving Achiampong speechless. “White people need to start saying NO to things and asking if there’s someone more suitable,” Joy Labinjo wrote, while Michaela Yearwood-Dan pointed out that, in a career that spans almost four decades, Quinn had “only just realised racism was important enough for you to make work about”.

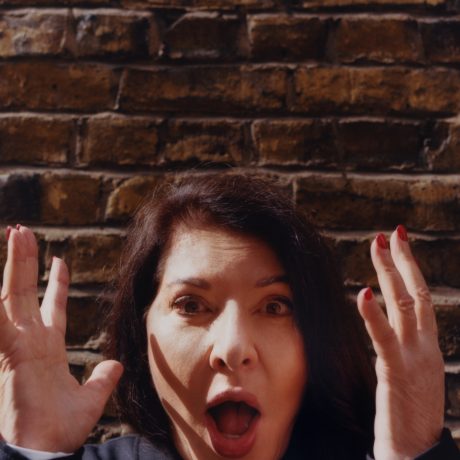

- Marc Quinn portrait landscape (right); A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) 2020, Marc Quinn, 2020. Image copyright Marc Quinn studio (left)

“Quinn could, and should, do better to confront why he ought to be the person to commemorate this moment”

Quinn’s performative sculpture in fact bears a close resemblance to the work of Thomas J Price, recently announced alongside Veronica Ryan as the two artists commissioned to create new sculptures in Hackney honouring the Windrush Generation. Price was among the first artists to speak to the press about Quinn, saying it felt like an “opportunistic stunt”. Price also wrote a riposte to the work, published yesterday by The Art Newspaper, in which he states, “while many non-Black people took a moment to consider how to de-centre themselves in discussions about race, Marc Quinn, an established white male artist saw an image.”

“I think it would be more useful if white artists confronted ‘whiteness’ as opposed to using the lack of Black representation in art to find relevance for themselves,” Price states. At the very least, if Quinn could not bear to pass up the opportunity to capitalise on the momentum of this moment, he could, and should, do better to confront why he ought to be the person to commemorate it. He needs to go beyond his current explanation of an uncontrollable urge to simply evoke an image.

What Quinn has successfully proved is that a large majority of non-Black people still do not understand systemic racism and how it manifests itself. Sadly, despite the statue being removed by Bristol City Council less than 24 hours after it appeared (it is being held by a museum ready for Quinn to collect) Quinn is now at the centre of this narrative. His name and his work overshadows the experience of Jen Reid, the black woman who attended the protest, and what that was intended to represent. It was she who was involved in the movement, and who performed the real act of defiance and power.