Needlework might not be the first art form that comes to mind when considering the vanguard of contemporary art that is the Venice Biennale. Twee, crafty, quaint, naïve: all are words that have been employed to describe a practice historically seen in terms of domesticity and the “feminine” sphere, and pigeonholed under “applied” or “decorative” arts.

This year, however, the creative capacities of needle and thread are given their dues. While big, bold, sculptural textiles are nothing new in Venice (think Sheila Hick’s enormous, knitted balls at the 2017 Biennale), the individual stitch is much more evident this time round. It is used to subvert stereotypes and retell the stories of cultures that are often misunderstood or misrepresented.

The Polish pavilion leads the way, inviting a Roma artist to exhibit for the first time in its history. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas has filled the space with 12 installations that allude to Hall of the Months’ fresco series from the Renaissance Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, Italy. In her version, she battles with anti-Roma rhetoric and tells histories from a female perspective, celebrating real individuals alongside mythological characters and astrological symbolism. All of this is done through ‘collaged’ textiles which are often torn-up garments belonging to the subjects of her works, or otherwise discarded materials. They are brought together by the most basic of running stitches, allowing for roughly hewn edges to fray.

In this new version of a Renaissance palace interior, dubbed Re-enchanting the World, the familiarity of the artist’s materials and simplistic stitching method encourages viewers to get up close and personal with the works. The installation is inviting and enveloping, in a way that a traditional fresco is not, perhaps because most people have at least some connection to mending and making (even if it’s a ham-fisted attempt to darn a sock) while fastidiously painted pigments remain elevated and removed.

“Stitching is used to subvert stereotypes and retell the stories of cultures that are often misunderstood or misrepresented”

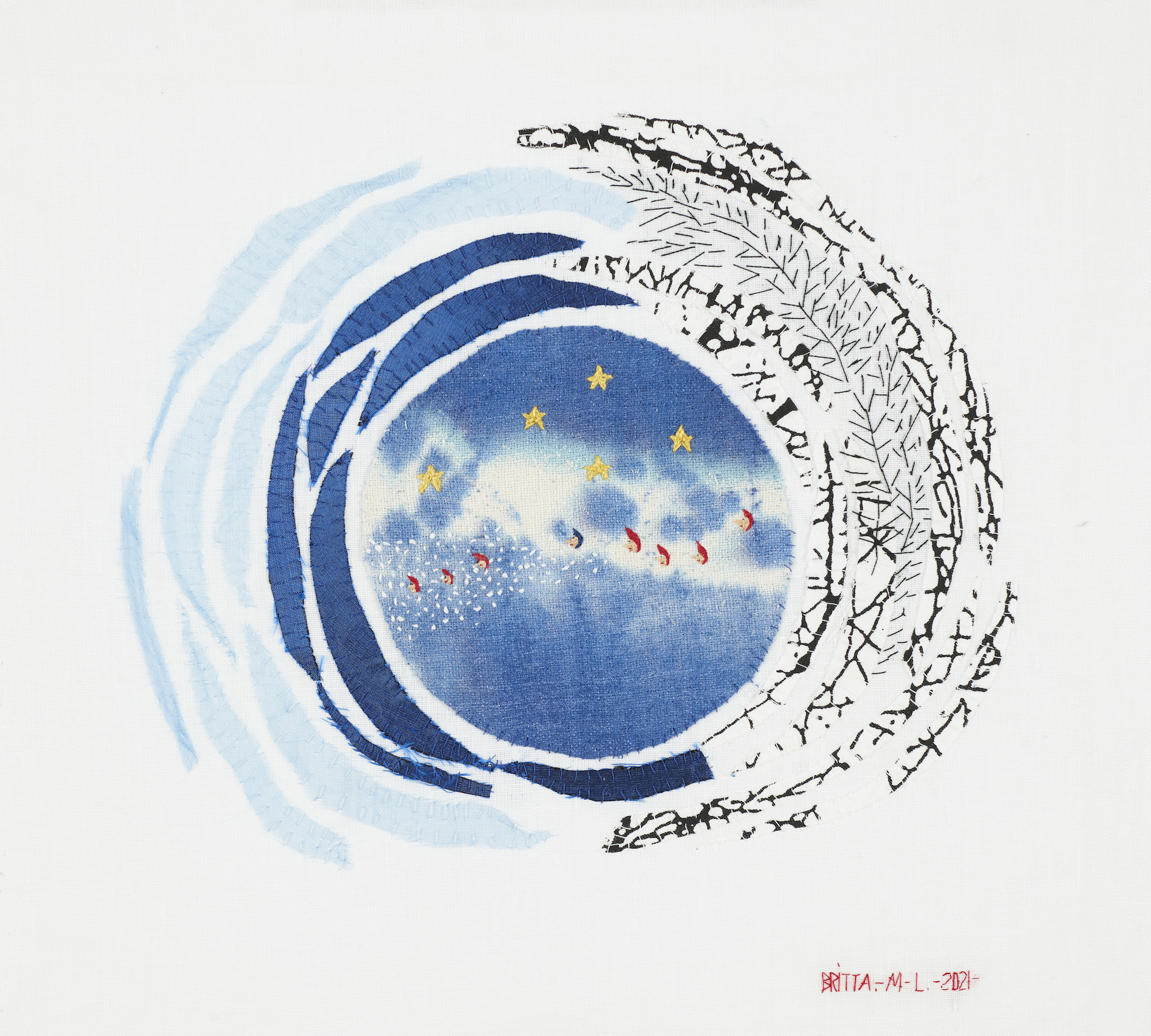

Britta Marakatt-Labba employs needlework on an even more intimate scale. Her beautiful diminutive works could easily be missed among the packed walls of the Arsenale, but given time, they offer a slice of life in Sàpmi, the home of the Sàmi indigenous community that has also taken over the Nordic Pavilion for this Biennale.

Marakatt-Labba was born into a family of reindeer herders, and her works reflect the realities of that existence, where sparse trees and dense snow are picked out in embroidery and appliqué, as well as more spiritual connections to the cosmos. A shining example is Milky Way where tiny, stitched scenes appear in a whirl of liquid colour.

Close by, Violeta Parra’s arpilleras form part of a larger history of embroidered protest within Chile. These dense, sewn works, traditionally made by women, combine braiding, patchwork, appliqué and more, to tell the realities of life under oppression, as well as weaving stories of ancestral legacy and pre-Columbian art. During the 1960s, Parra began making her own, despite already having a successful career as a singer-songwriter. She deemed these works “songs that paint themselves”.

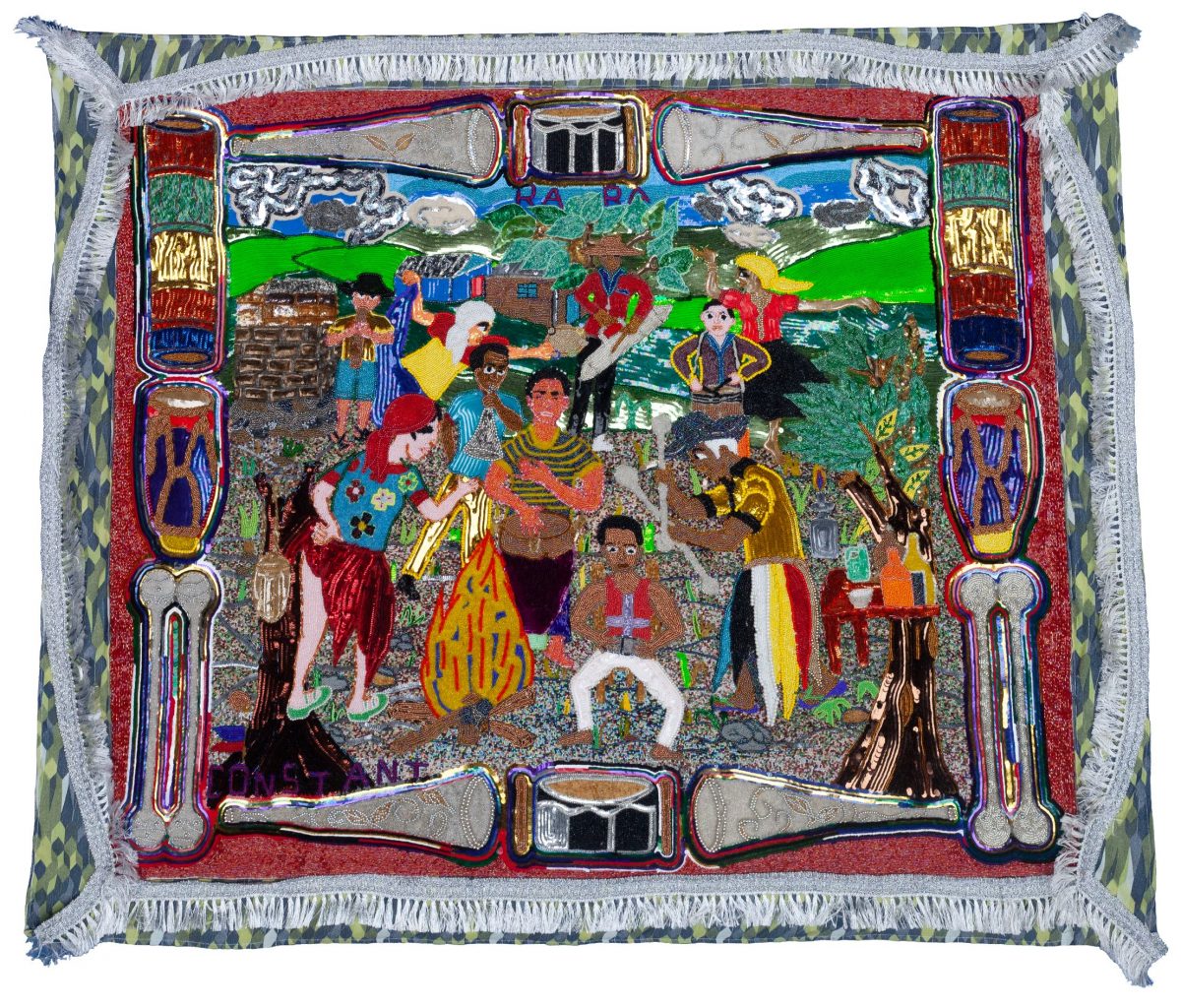

Although the humble qualities of the stitch are given their dues, the vibrant capabilities of needlework are also celebrated in the astonishing, heavily laden Drapo Vodou (handmade flags) of Myrlande Constant. After years of working in an all-male environment, she broke away to redefine the aesthetics of this traditional Haitian artform. She merges contemporary culture with religious symbolism, where plentiful feasts, musical instruments, spiritual figures and sea creatures come together, in astonishingly dense, glitzy canvasses filled with abundant textures. The physical weight of the objects is charged with the labour and skill of the embroiderers who bring them in to being.

“Sparse trees and dense snow are picked out in embroidery and appliqué, as well as more spiritual connections to the cosmos”

The weight of the art is once again felt in Igshaan Adams’ epic piece Bonteheuwel/ Epping, which forgoes the needle in favour of its close creative neighbour: weaving. The work is informed by the desire lines (unplanned routes favoured by individuals) between the Bonteheuwel train station in Cape Town and Epping, one of the city’s industrial neighbourhoods where many people go to work.

The architecture of the former Apartheid regime, and the resistance shown by everyday commuters, is reimagined by Adams through immense textiles which might seem closely aligned to traditional tapestry. In fact, they are formed from found materials such as plastic, bone, stone, nylon, cotton and wire.

The intricately woven patterns are a thing of beauty, but they speak to the contradictions and multifaceted existence of growing up somewhere like Bonteheuwel, where the innate joys of family and home stand at odds with the embedded history of segregation and oppression.

“The patterns are a thing of beauty, but they speak to the contradictions of growing up somewhere like Bonteheuwel”

At a time when slick fabrication and immense technological feats dominate the artistic vanguard, it is refreshing to see the evidence of time and labour so undoubtedly visible in these works. In the eyes of these artists, each thread is far more than a mere mark of process. It is a vital part of a conceptual framework that celebrates everything from indigenous traditions and religious ceremony to the invisible labour and hidden social systems in which we all live.

Holly Black is Elephant’s managing editor