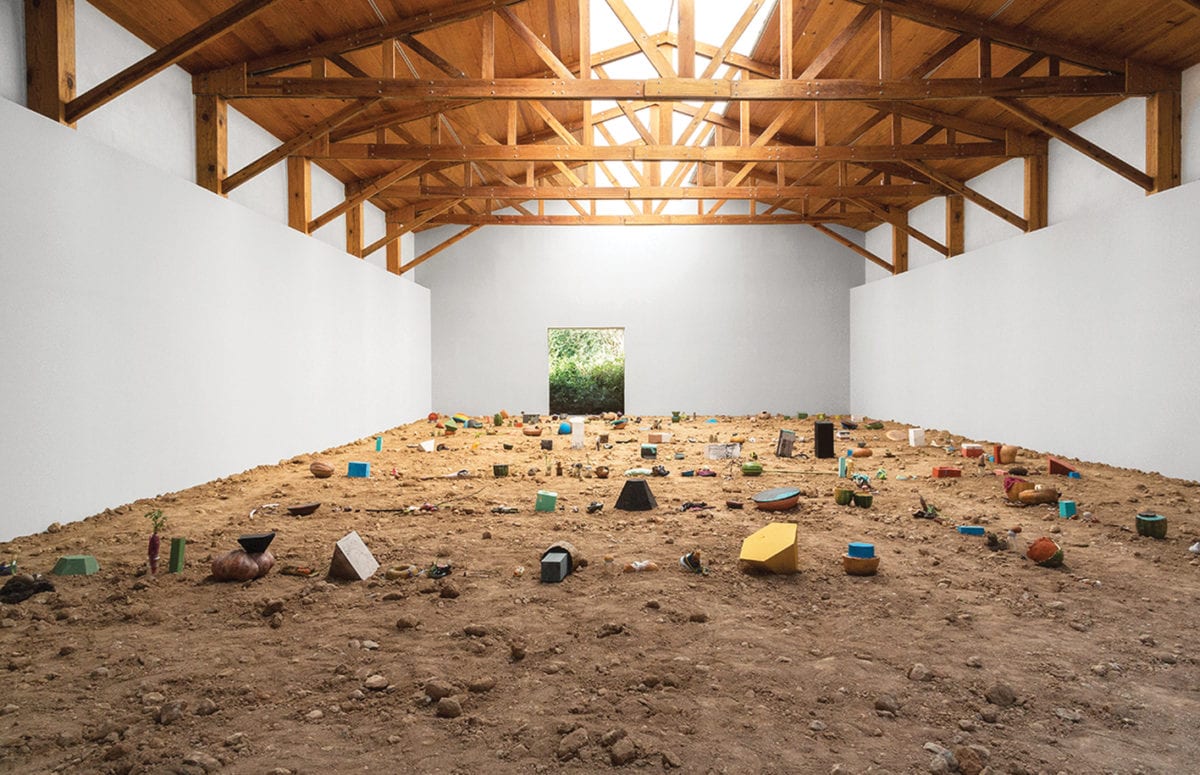

- Kurimanzutto, Mexico. Photo by Onnis Luque, 2016

When I meet Mónica Manzuttoand José Kuri in their Mexico City home—an exotic oasis where lush vegetation, artworks and rescue dogs coexist in elegant harmony—they are feeling worse for wear. It is several days after the opening party for Sarah Lucas’s exhibition at their gallery nearby, which involved drag performances and much egg throwing, and Kuri still seems to be feeling the pain. “It was fantastic, I’m still recovering,” he says in a hoarse voice.

Kurimanzutto, which turns twenty this year, is Mexico’s most influential commercial gallery. Its roster of thirty-three Mexican and international artists includes Carlos Amorales (who represented Mexico at the 2017 Venice Biennale), Minerva Cuevas, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Leonor Antunes. The gallery occupies a pivotal position within Mexico’s thriving contemporary art scene, which boasts an impressive array of museums, galleries, artist-run collectives, an annual art fair, Zona Maco, and an alternative fair Material. But in the late nineties, when Kuri and Manzutto began organizing experimental exhibitions for their artist friends, the infrastructure was sparse, with few galleries and collectors interested in the work.

Hailing from Mexico and Argentina respectively, Kuri and Manzutto met at university and had no formal art history training but shared a passion for art. Kuri’s childhood friend, the artist Gabriel Orozco, suggested they form a nomadic gallery to exhibit young artists such as Damián Ortega, Abraham Cruzvillegas and Gabriel Kuri (José’s brother), who Orozco had been teaching. At the time, those artists and their peers were making conceptual, socially engaged art in a rejection of neo-Mexicanism, which glorified a stereotypical notion of Mexican identity in kitsch folkloric paintings. Orozco’s contemporaries, by contrast, made poetic and powerful art that commented, obliquely or directly, on issues such as political corruption, the impact of neoliberalism, NAFTA, globalization and the drug cartels.

So Kurimanzutto began life without a home. “Using the city as our gallery was very attractive. Mexico City is a great city with a lot of possibilities so we thought we should take advantage of that,” says Kuri. Their first show, Market Economy in 1999, took place in a market stall and lasted one day. Among the fourteen artists who participated, Ortega memorably reconfigured plastic action figures with crab parts and fresh produce to create weird hybrid transformers that simultaneously embodied fragility and strength, decay and durability, and spoke of the globalized era as toys flooded Mexico from China and Taiwan. “There was clearly some sort of game there, opening a gallery inside the market and selling the work for the prices of the market goods,” notes Manzutto. “That was the first time we understood how important the idea of not having a fixed base was going to be and the kind of energy we would have.”

- Adrián Villar Rojas - Los Teatros de Saturno, 2014

Innovation being a natural bedfellow of flexibility, shows ensued in a carpet store, in the airport, in a supermarket parking lot, in a cinema and in the container of a semi-trailer truck. For the first two years, all the artists featured in their shows “so we could grow together”, says Manzutto. “We were just working from a telephone line which was our apartment. Me and Monica, and whatever the artists needed for an exhibition,” says Kuri. “We recently checked our papers and found we were living off $300 or $400 a month, but we didn’t notice. We felt very lucky to be doing this.”

With no overheads or financial obligations, the pair, who have been together for more than twenty-five years, travelled frequently and forged relationships with international museum directors and curators. They made ninety percent of their sales abroad until Mexico’s domestic art world caught onto the talent on its doorstep. Now around forty percent of the gallery’s sales come from Mexico. But the key to their success, says Kuri, lies unquestionably in the close friendships they have with their artists. “We still go to them to discuss our shows and ideas,” Manzutto tells me. “It’s very collaborative.”

“We recently checked our papers and found we were living off $300 or $400 a month, but we didn’t notice”

“One of Kurimanzutto’s great contributions was that they consolidated this historical moment of artists working in the nineties by tapping into and creating a market for those artists at an international level and giving them visibility in biennials, fairs and institutions,” says Chris Sharp, an independent US curator and cofounder of an alternative gallery space in the city called Lulu.

By 2008, Kuri and Manzutto had the responsibility of children, and the gallery needed its own permanent space. That year they opened a spectacular premise in a former cake factory. Bursting with tropical foliage, flooded with light, the converted complex comprises an office, library and a wood-beamed exhibition hall imbued with a distinctly Mexican ambience. At its core is an inviting social area with kitchen and bar, an essential consideration for the gregarious couple—“things happen when we are there with our friends and artists drinking and dancing,” says Manzutto.

“One of Kurimanzutto’s great contributions was that they consolidated this historical moment of artists working in the nineties by tapping into and creating a market for those artists at an international level”

Nowadays Kurimanzutto’s Mexican artists have become international stars and regularly feature in biennials and prestigious museum shows around the globe. Equally important to the gallery’s founders is the dialogue between Mexico and their foreign artists. “It’s part of what we can give back to them when they come here,” says Manzutto. For instance, Vietnamese-born Danh Vō has been researching natural red pigment used by the Spanish conquerors, which connects to his interest in the economics of colonization. In 2012 the gallery staged Sarah Lucas’s first Mexican show in the Museo Anahuacalli, which houses Diego Rivera’s extensive collection of pre-Hispanic objects, rather than in their own gallery. Lucas was also given a residency in Oaxaca, enabling her to respond to Mexico’s heritage and her surroundings.

Kuri and Manzutto continue to orchestrate creative exchanges beyond the gallery’s boundaries, such as last year’s exhibition at Thomas Dane Gallery in London in homage to the pioneering sixities art gallery Signals London which ran from 1964-66. The historic show comprising 120 works was Kuri’s brainchild and captured the experimental, cross-disciplinary spirit of Signals, which was founded by David Medalla, Gustav Metzger and Marcello Salvadori with the aim of forging new relationships across different aesthetic tendencies such as constructivism and kinetic art among artists from Latin America, the US and Europe. Kurimanzutto has just opened a small outpost in New York where they plan to present a handful of site specific artists’ projects annually but, as Kuri says, Mexico remains their centre of gravity. “I think the more local we are the more relevant we are. Otherwise we will dilute ourselves.”