Earlier this year, the first signs of pandemic “lockdown life” were the closure of physical communal spaces: schools and colleges, galleries, museums, theatres, music venues, bars and restaurants. Self-isolation quickly amplified every element of life, jolting the rhythm of the everyday, which skittered between torpor and high tension. As many countries now find themselves out of lockdown to some extent, a discomfort remains around spaces which support mass gatherings, and music venues have been some of the worst hit.

In place of people not being able to get together physically for live music events, a digital flurry of online gigs, film clubs and album-listening parties have emerged. Earlier in the year, stadium-sized acts started to stream intimate “living-room” sets and invited questions from the global crowd. On the grandest mainstream scale, there was Lady Gaga, at the helm of a World Health Organization online concert One World: Together at Home, in support of under-protected and underpaid healthcare workers.

- Christine and the Queens livestream

Technology sparks connections and simultaneously creates dissonance; often, this remote community feels bittersweet (seeing a blur of friends’ faces at my first “Zoom rave” just made me feel melancholy). Occasionally, it feels off-key: nobody needs to endure a string of US celebs simpering their way through a John Lennon singalong. But most significantly, remote collaborations and communities suggest new possibilities that should resonate far beyond this highly unusual year. This has been a time for independent spirits to thrive, and it’s been galvanizing to see and hear innovative artists create their own makeshift gigs. They include Soweto Kinch’s politically charged “Lockdown Sessions”; Christine and the Queens’ endearingly surreal “Version Confinée” performances; and a blaze of turntable battles hosted on Instagram Live.

“I use culture as my vehicle to connect communities, cultivate creativity and celebrate human diversity”

Artists have arguably always collaborated remotely, whether exchanging and shaping ideas by letter or digital forms. In the mid-nineties, US media artist and programmer Nora Farrell and composer William Duckworth launched pioneering “internet band” project Cathedral. It was described by Duckworth as comprising three components: “the website itself, which features a variety of interactive musical, artistic and text-based experiences; the PitchWeb, which is one of the virtual instruments designed for the site to allow listeners to play together online; and the Cathedral band, a group of improvising musicians that gives periodic live performances from venues around the world”. Similarly, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, indie super-group The Postal Service were famed for their old-school means of communication: bandmates would initially post CD recordings to each other, adding their own parts. And let’s not forget, archaic social media sites such as MySpace were once hotbeds of musical connection.

“The collaborative spirit is my eternal spirit,” says multimedia innovator Michael Barnes-Wynters. Growing up in Bristol, the eldest child of three in a Jamaican household, young Barnes-Wynters’ creativity was encouraged by his mother, who allowed him a section of wall on which to “doodle” ideas. He recalls: “Giving me that opportunity manifested itself into my finding neglected, overlooked and unsanctioned spaces to instigate opportunities for folk to step into these found spaces and collaboratively create magical moments.”

By early adulthood, he was living in an infamously musical house-share on Bristol’s Cheltenham Road (name-checked in music histories such as John Robb’s book The Nineties: What the F**k Was That All About?) alongside seminal producer-engineers Rob Smith (Smith & Mighty) and Dave McDonald (Portishead), and using his pre-digital communication skills to make art collaborations happen. It was a technique that continued when he moved to Manchester in 1993, where he developed his Doodlebug platform, associated with “bedroom talents” turned major stars including Mr Scruff, Twisted Nerve’s Andy Votel and singer-songwriter Alison David.

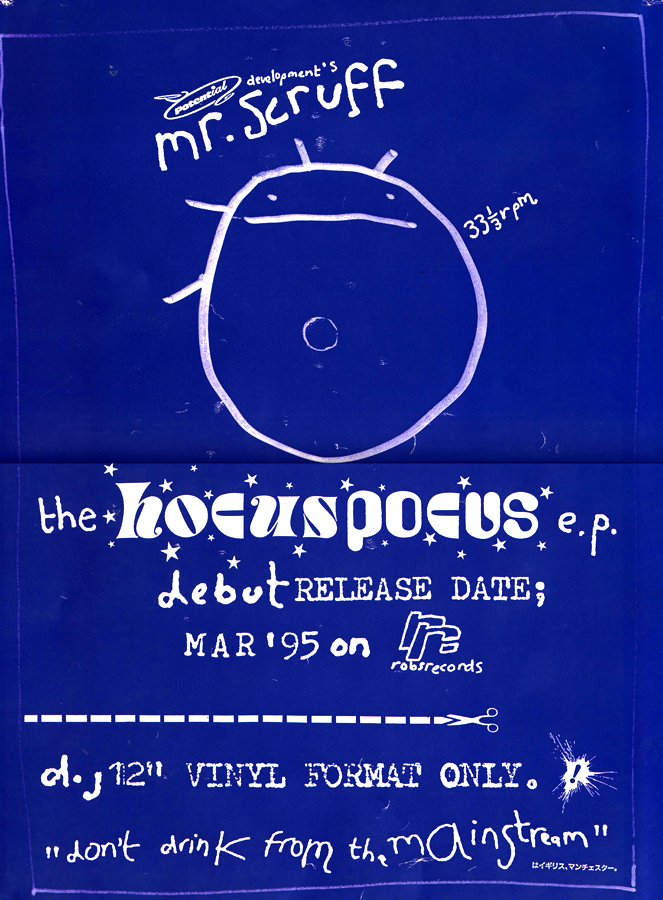

“Working collaboratively in the mid-1990s with the then-unknown Andrew Carthy (aka Mr Scruff), using our telephone contacts, fax machines and the post, proved successful as we were able to create a world in which we invited everyone to enter with his first release, named after one of my limited-edition club nights, the Hocus Pocus EP [1995],” says Barnes-Wynters. “I use culture as my vehicle to connect communities, cultivate creativity and celebrate human diversity, to ultimately empower ‘the underdog’ to become today’s future creative entrepreneurs and community leaders; this philosophy is at the heart of everything I do.”

Barnes-Wynters’s prolific creative flow has pulsed across genres and scenes ever since, whether it’s connecting global artists in his liaison role for the Womad festival; creating annual International Doodlebug Days (1998–2006) across Manchester, London and Tokyo; or as a senior curator of independent artist platform Contact, and “community-based radical arts space” Niamos.

Now based in Hull, one of his latest projects, Take Back Control TV, was originally developed for The Lowry gallery in Salford, but takes on a new online life of its own, drawing from the febrile history of public access and community-television programming, and inviting new submissions to the mix. Barnes-Wynters relates the Chinese-language interpretation of the word “crisis” as comprising the symbols for “danger” and “opportunities”. This is, he says, “the lane in which we creatives live and flex”.

- Self Esteem portrait by Charlotte Patmore

The physicality of experimental pop star Self Esteem’s work is part of its brilliant allure; it’s there in the taut electro rhythms of her tracks including Your Wife, and the splendidly weird and slinky choreography of videos such as The Best. If Self Esteem (aka Rebecca Lucy Taylor) can’t get physical, then she definitely gets digital; while countless acts have streamed “lockdown gigs”, Taylor agreed to host an entire music festival via Instagram: the femme-centred Pxssy Pandemique.

“Hosting the festival taught me a lot: how you shouldn’t fixate on micro-managing things, how beautiful things can emerge unexpectedly,” says Taylor, laughing. “I just set it up in my mum and dad’s bedroom, where my wi-fi is strongest, and chatted with my friends throughout.” While the festival wasn’t entirely glitch-free—the webcast got blocked following performance artist Natalie Wardle’s set, which featured fleeting nudity—Taylor embraced its sense of community, and credits “technology, plus going solo” (she was previously half of acclaimed Sheffield indie-folk act Slow Club) for her creative autonomy.

“I do like working remotely, because I get to take advantage of these surges of energy, and when I can be ‘switched on’,” she explains. “Being able to upload your own material definitely works for an artist like me, who’s got a fuck load of catalogue. Producers have always sent me beats, and I’ll write over them; if I’m on a similar wavelength with someone, the physical distance doesn’t matter. In fact, I like working with people who don’t have the same goal; the hardest and best aspect of being a solo artist is that I only have my own angle on things.”

“Hosting the festival taught me a lot: how you shouldn’t fixate on micro-managing things, how beautiful things can emerge unexpectedly”

Remote performance definitely brings its own sense of intimacy, as Taylor has since streamed live sets from her childhood bedroom. “It’s the scene of 10,000 tantrums!” she chortles. “I can’t sleep in that room now, but I can play a gig in it.” She adds, “I have started to have a rapport with an audience, in a way that I hadn’t imagined. The IG Live chat comments have felt so full of love and positivity, from the people who respond to the shit I’m doing.”

“Art is how we face the world when we can’t face the world,” murmurs Will Gould, the frontman of gloriously florid Southampton rockers Creeper. Since their 2014 formation, the band have fostered a heady rapport with their fanbase, incorporating internet trickery and interactivity (including an online text-based game, Mainframe). However, the build-up to their second major label album, Sex, Death & the Infinite Void, also proved a painful personal challenge and, ultimately, a triumph of creative camaraderie.

In 2018, Creeper guitarist and co-writer Ian Miles was sectioned, following serious mental health issues; he and Gould had been due to fly to LA to create the album, but Miles’s wife persuaded Gould to continue with the sessions. “I had to be talked into it,” admits Gould. “Her fear was that if we put the band on pause, we’d never come back, and that when Ian finally came around, he’d have lost the biggest thing in his life. There was an empty seat next to me on the plane going out there; it was a very heavy thing.”

Gould would gradually renew his connection with his friend and bandmate, via long-distance calls and FaceTime. “Ian’s wife got him an acoustic guitar, and he started to communicate with music,” recalls Gould. “He’s a hyper-creative individual. He started painting for the first time and making these amazing works.” He continues, “We were in different time zones, of course. Me and Xandy [Barry, album producer] would record a version of an idea, and send it to the UK when we were leaving the studio; Ian would record the guitar parts, and we’d find them when we woke up. It was like working around the clock; when we put our tools down, Ian would pick them up.”

Gould would eventually succumb to exhaustion following the LA sessions, but he recalls: “Just as I started to tap out, Ian took over the sessions in London. I think the record has a lot of British glam rock and Britpop influences, and an American sheen, including the LA Philharmonic. We were able to do that via this remote working space, and a big Dropbox folder! Technology is the magic of our current age.”

“What’s surprised me is that you can get a sense of intimacy and connection within a remote session”

My first experience of Swedish-born DJ and producer Johan Hugo was through his sweaty yet scintillating Secousse parties, organized with Radioclit partner Etienne Tron at Notting Hill Arts Club, a buzzing West London basement venue. Since then, Hugo has relocated to the coastal town of Margate and created contemporary global music through projects including The Very Best (featuring Malawian vocalist Esau Mwamwaya and guests such as Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig), and his productions for the likes of MIA, Lazarus, Mumford & Sons and Senegalese superstar Baaba Maal. Hugo’s home studio remained remarkably busy during lockdown.

“This period has been eye-opening for me,” he says. “I’ve always done a lot of remote work; when the internet first exploded we’d send beats to a rapper, and they’d send a feature vocal back, but now we’re doing sessions on Zoom and using tech that allows you to mix live in real time and in high fidelity. What’s surprised me is that you can get a sense of intimacy and connection within a remote session. I put a table and screen where the other person usually sits in my studio; it’s my natural thing to turn to my left and look at someone.”

Hugo maintains that chemistry is still the key to remote community, as much as it would be in person. Still, he has a knack for persuading collaborators to come on board. As a teen, he would regularly call up his heroes, such as the Boston poet-rapper Mike Ladd, who he eventually met and befriended IRL. Hugo reminisces about the unpredictable thrill of old-school communication (“You’d be sending out beats, not knowing if you’d ever get something back”) but also revels in an age where tech brings immediacy and intimacy. “I’ve always found the challenges in music really exciting and inspiring; I do think that it brings something out of us,” he says. “It’s humbling, because everyone is in a place where they’re not as secure, which creates a more level playing field and removes ego. Once you just go for it, things get done.”