Nick Cave is the ultimate man-as-brand, bringing his unique and instantly recognisable aesthetic to everything he engages with. He seems to live and breathe the elements that make him and his music so individual, and it would be difficult to say where the man stops and the megastar begins. He is also one of music’s foremost crossover artists, infusing his work with elements of literature, poetry, fashion, biography, religion and more.

It makes perfect sense then, that his 2014 scripted documentary 20,000 Days on Earth would be directed by artist duo Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard

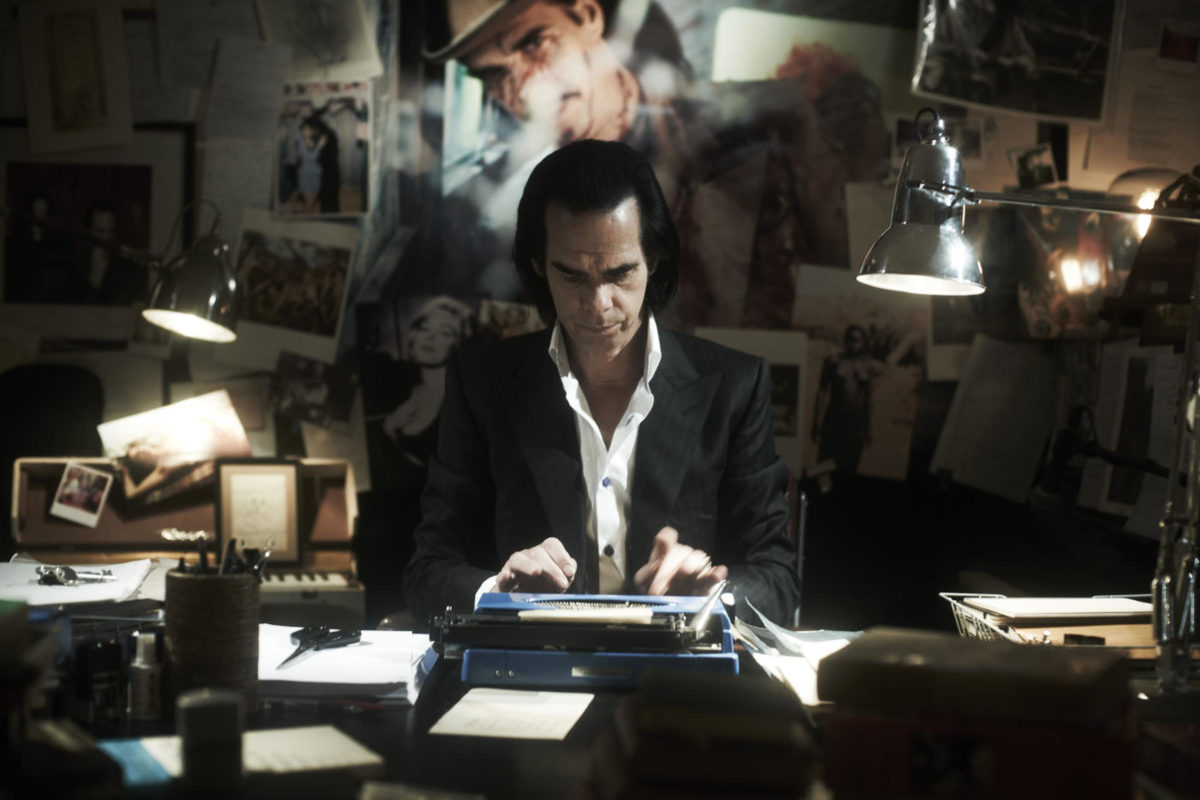

, who also nimbly straddle the worlds of sound, music and contemporary art. The resulting film, which Cave retained a high level of creative control over, reads less like a typical warts-and-all music documentary, and more a highly considered and stylised glimpse into a rigorous creative process.

Forsyth and Pollard bleed Cave’s distinct look and feel into every element of the film’s inky aesthetic, which happens to chime incredibly well with their own. 20,000 Days on Earth invites its viewers to fall into Cave’s world, which blurs fact and fiction, and brings together the everyday, gut-felt emotions of falling in love or being dumped alongside glamourised murder and fantastical mythology. In this world, there is no simple truth to grasp; the joy of it lies in surrendering to the story.

“20,000 Days on Earth invites its viewers to fall into Cave’s world, which blurs fact and fiction”

The musical documentary format has been well used over the years, leading to infamous spoofs such as Spinal Tap, as well as recent Netflix offerings which delve behind the scenes with pop icons such as Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift. There is often the promise of glimpsing the “real” person, and seeing what goes on behind their superhuman public fronts.

This almost always feels like a pretence; there is no logical reason for a multi-millionaire musician to put something out that doesn’t chime with or play into their trademark persona, even when (closely managed) revelations are involved. Plus, in the age of social media and oversharing, the binary of public and private realities is becoming harder and harder to untangle.

20,000 Days on Earth does away with the pretence of proximity, revelling instead in the creative and experimental elements that make Nick Cave the tremendous cultural presence that he is, and reflecting on his own godlike image. In doing so, it digs into what really comprises a musical artist at Cave’s level. Truth and façade are consciously recurring themes, running through his intimate yet staged conversations with a shrink-like figure, his musings on the consistency that is required of rockstars (reinvention, he tells Ray Winstone, is not an option for him), and his dramatically shot conversation with Kylie Minogue, who sits in the back of his car while he drives through Brighton’s dark streets.

Cave exists within an unusual sphere for a rockstar. Despite the consistency of his vision and public character in many ways, he has evolved musically numerous times. Unlike many musicians who came to prominence more than a couple of decades ago, he doesn’t sell himself based purely on his older material. He seems no more tied to his debut 1984 studio album From Her to Eternity, or his 1990s period of Let Love In and stirring Murder Ballads, than he is to the haunting beauty of recent albums Skeleton Tree and Ghosteen.

- 20,000 Days on Earth. Courtesy Lifestyle Pictures / Alamy Stock Photo

“Truth and façade are consciously recurring themes”

He has nimbly moved his sound between punkish rage and spine tingling serenity over the years, and both exist happily alongside one another in his live performances. It is rare for someone to experiment so hugely in sound and still hold onto a very solid core of what makes them individual. He also retains an untouchable cool while opening up much of his process to fans, from selling “Red Right Hand” charms on his website, to answering personal letters via the Red Right Hand Files newsletter.

One More Time with Feeling, the 2016 film that followed 20,000 Days on Earth, conveys the raw reality of loss, as Cave’s family grieve the death of his teenage son, and documents the influence of this experience on Skeleton Tree. Most recently, he has opened up his archive for public exhibition at the Black Diamond in Copenhagen. The Gucci-supported show brings together hundreds of items in a “multi-sensory exploration of his many real and imagined universes”.

Towards the end of 20,000 Days on Earth, Cave describes songs as “veneers”. The truth lies behind the words, he says, but the real pleasure can be found in seeing that flash of something, and feeling rather than fully understanding it. This film doesn’t try to show the banal truths of Cave’s life, just as his music never does. But it does offer full immersion into authentic feelings and themes that are far greater than that. In the end, it’s the things that lie beyond our direct realities that have the power to really move us.

Stranger Than Kindness: The Nick Cave Exhibition, supported by Gucci

Until 13 February 2021 at The Black Diamond, Copenhagen

VISIT WEBSITE