NS Harsha considers the world around him on a universal scale. The Mysore-based artist, who is renowned across India, utilizes seemingly every material at his disposal to explore his ideas. He works on paper and in paint to create his own versions of traditional folk tales, produces vast, meticulously crafted images of celestial planes on canvas and fabric, as well as enormous, site-specific installations that utilize found objects and sculptural forms.

In fact, Harsha’s practice is so broad that you would be mistaken for thinking that there were several different artists exhibiting at Victoria Miro’s Wharf Road location. For example, on first look, the colossal installation that dominates the entrance and extends up into the floor above seems to be its own beast, will little connection to the delicate fabric paintings that surround it.

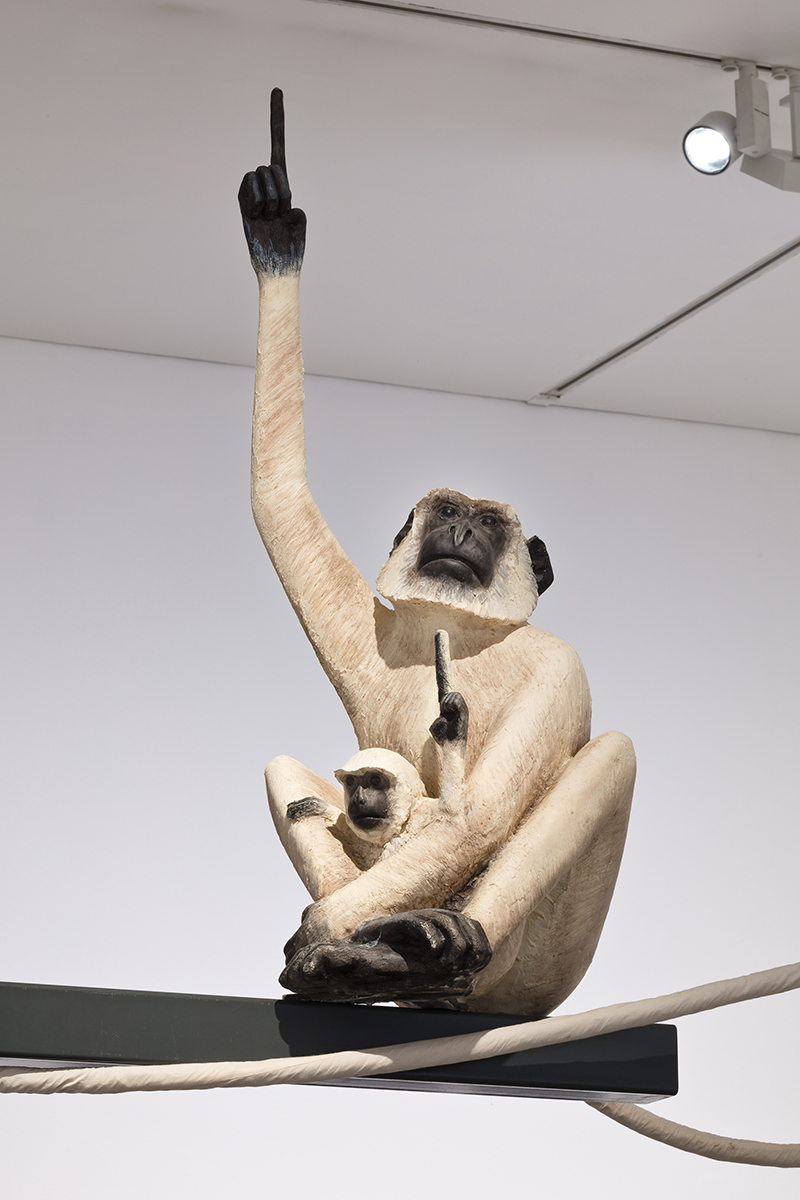

This massive sculpture features several monkeys sitting astride a large metal frame. They all ominously point upward, as if calling to an impending force descending from the heavens. It is at once compelling (we are all naturally drawn to the wonders of wildlife) but also unsettling, especially as the primates’ tails appear fused together.

NS Harsha, Warmth, 2019 © NS Harsha, Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

“Have you ever heard of a rat king?” the artist enquires, as we explore the exhibition. I am ignorant, so he explains that it is a phenomenon where hibernating rats get their tails tangled up, making it impossible to move independently—the result is fatal. Harsha tells this story with an amenable grin, despite my horror, and it is this jovial sensibility that infuses his work, even when he is dealing with subjects of existential significance.

Case in point, while considering his acrylic painting Warmth he gestures towards the huddled groups of people that appear to be floating through the cosmos and paying mind to an array of traditional and contemporary deities, including an astronaut and a terrifying skeleton clutching a newborn baby. “I added the tortoise and the donkey because it was getting too heavy!” he chuckles.

The motif of stars and planets is a common occurrence in Harsha’s work, and is found again among pieces of fabric pegged to strings, as if they are on a washing line. I wonder why these carefully decorated swatches have been arranged in triplets, and once again the answer is rooted in humble aims: “If you hang something on its own, you’re making a statement. I hung these in threes so that they won’t be taken too seriously. They look like clothing out to dry, they could be a T-shirt, a skirt, a sock…”

“We are always told that the truth is somewhere out there, but if that is correct does that means that what is right here is here is a lie?”

There is certainly something approachable about these works, which invite you to step closer and pick out the tiny details of various cosmic objects. The repeated presence of this pattern reveals something of an obsession for Harsha, who enters his own rhythm while painting an imagined universe, even when his friends pop round. “I am very interested in the idea of the cosmos,” he explains. “We are always told that the truth is somewhere out there, but if that is correct does that means that what is right here is here is a lie?”

It’s a heavy supposition, which also exists at the centre of his second major installation Reclaiming the Inner Space, on show on the upper floor. It comprises a collection of flattened pieces of packaging mounted on mirror, which appear stacked above and below thousands of carved wooden elephants. The figurines appear to burst forth like a stampede, while an intense splatter of paint is once again decorated with the dense cosmos, as if the entire fabric of space and time has been torn open.

It is a lot to take in, and it is easy to get lost navigating the complex packaging nets that encase everyday products, or glimpsing fragments of your own face within the mass. The work speaks of mindless consumerism and invisible labour, signified not only by the vision of an elephant, which Harsha points out are historically depicted carrying weight, but the craftsmanship that has gone into making these everyday tourist objects.

These ideas are related to the increased industrialization of Mysore, Harsha’s longtime home, and where “supermarkets only arrived about fifteen years ago”. He is interested in watching the gradual change in the area, which he has mapped through the epic amounts of packaging that he found readily available. “The supermarket is the darkest place there is, because every single package contains its own darkness.”

NS Harsha, Smears to Weave Her Everyday, 2019 © NS Harsha. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

This conceptual collapsing of space strikes a tone that carries through in the raw brushwork that is evident not only in Reclaiming the Inner Space, but smaller paintings, where a single mark or a thumbprint is adorned with thousands of stars. It is as if the artist has thrown his whole body into the work, freezing a moment of action in what he refers to as “feeling like the whole body and mind comes together in that one gesture—something just has to feel right”.

In many ways it is that emotive force that pulls Harsha’s work together. As a viewer you might originally consider these works disparate, but small signifiers (the prevalent cosmos, or the odd elephant) and a unifying sense of wonder gradually knits everything together. It seems that Harsha is on a constant search to make sense of the universe on his own terms, in whatever fashion that calls to him, but he will always maintain a modest outlook concerning the power of his art: “the artist doesn’t just make the work, the works makes the artist too.”