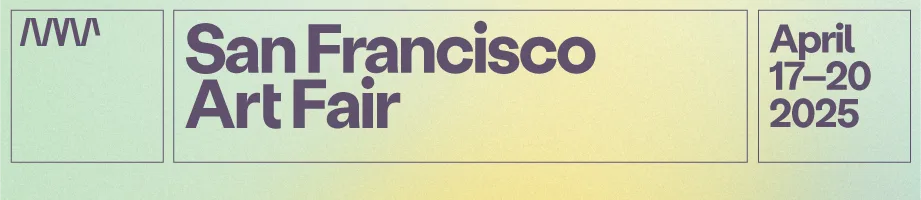

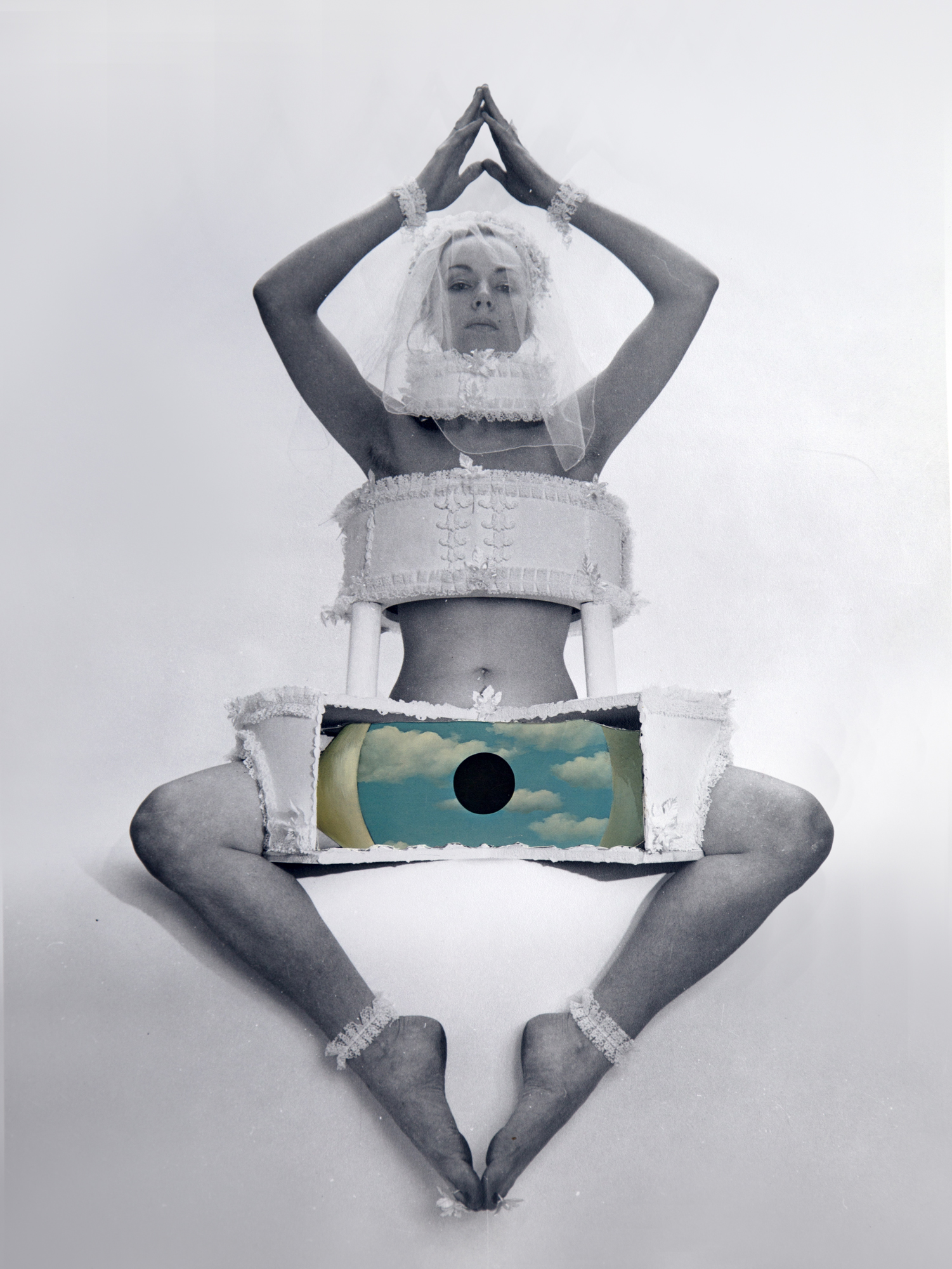

Transgression radiates from the work of British artist Penny Slinger. It has spanned everything from experimental theatre productions to sardonic nude self-portraiture in which she appears as a wedding cake, complete with a removable slice exposing her genitals.

With her progressive perspectives on abjection, sex work, desire, and the limitations of gender roles, Slinger anticipated the rising feminist movement in art. Her collage work from the 1970s, meanwhile, has since been heralded as a precursor to the punk movement’s disobedient aesthetics. Her visceral commentary on the constraints placed by society upon women has gone on to influence artists such as Linder Sterling and Throbbing Gristle co-founder Cosey Fanni Tutti. Yet at the end of the decade, she would turn her back on the art world to go it alone.

Does Slinger still want to shock audiences with her art? “Shock tactics,” Slinger explains on a video call from her studio in Los Angeles, “crack open the hard shell to allow access to the sensitive awareness that lies within. If art cannot shift your perception and sense of reality in some way, then it is not doing its job.”

Emerging as an artist in the late 1960s, Slinger studied art at Farnham and then Chelsea College of Arts. Working across media, in sculpture, painting, photo-collage, experimental film and performance, Slinger quickly tapped into the visual tactics of surrealism.

“I felt the art scene was elitist. I wanted to reach out further”

The movement’s concern with sexuality, the subconscious and dreams offered her a redolent visual language for mining the mysteries of female consciousness. Her interest in the subversive potential of collage started young. “I started experimenting with collage when I was a little girl sick in bed. I would take magazines, tear things to pieces, and create collages with different areas of colour,” she says. However, it was an encounter with the work of Max Ernst, a central figure in the Dada and surrealist movement, that really showed her the possibilities of the medium.

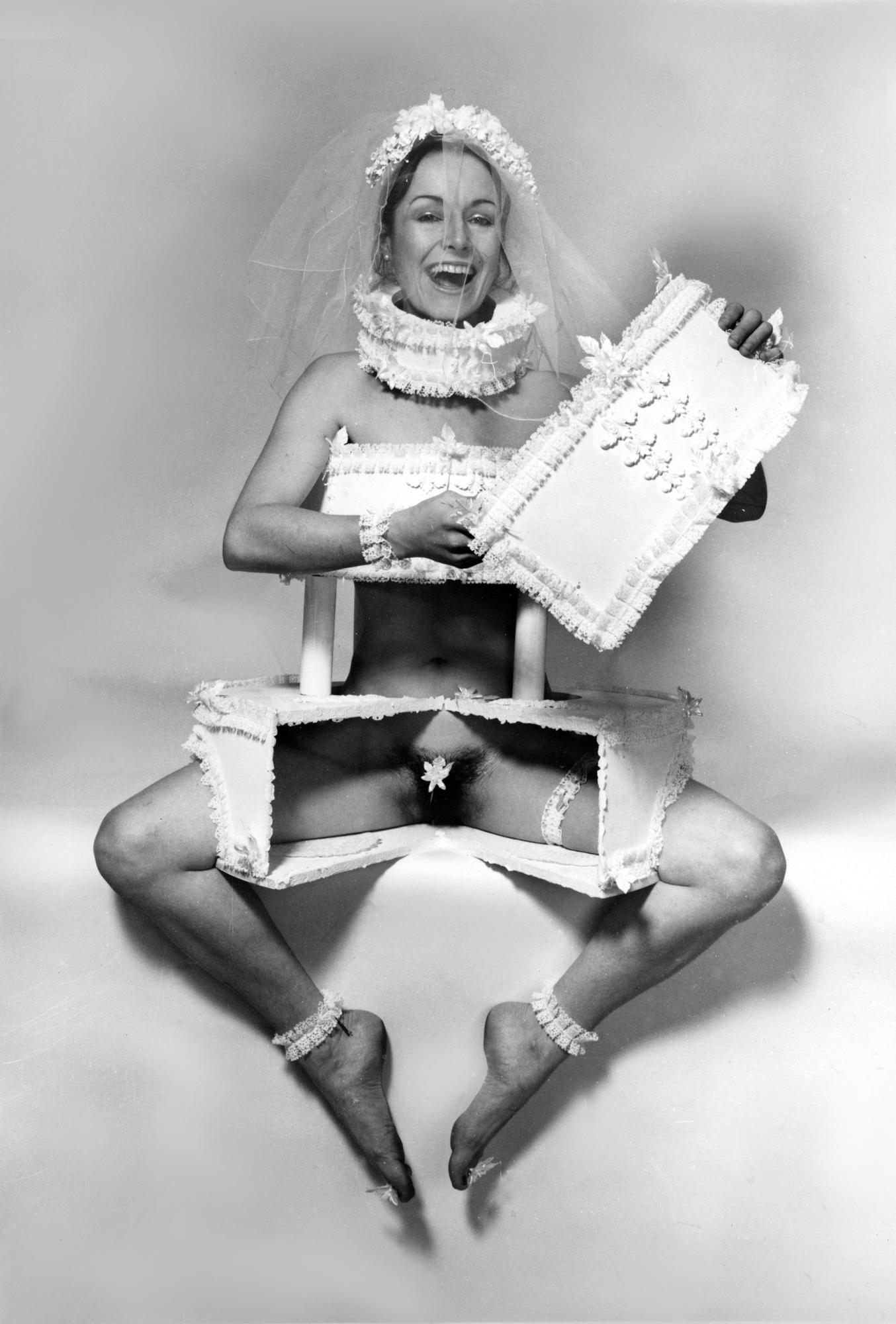

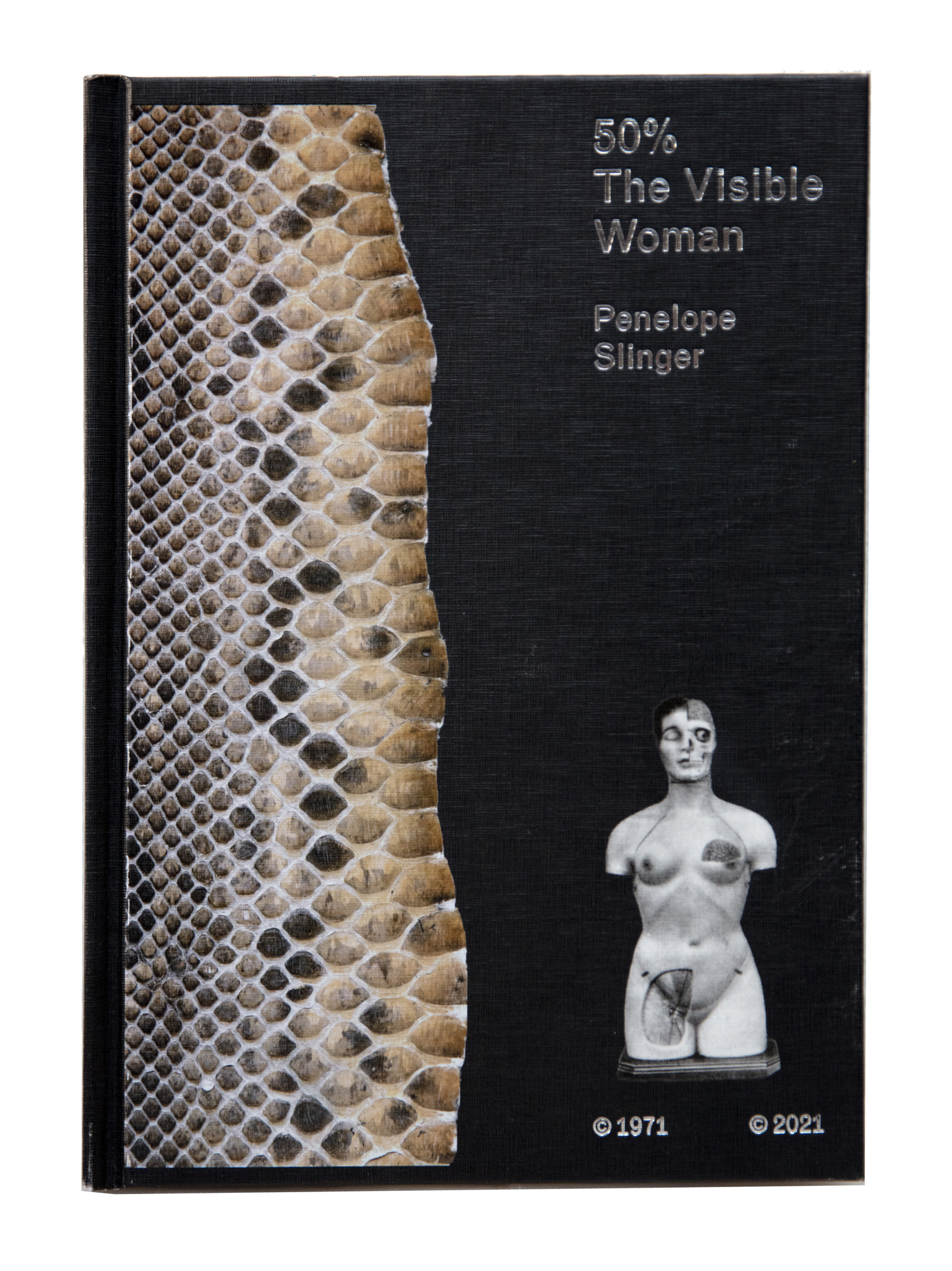

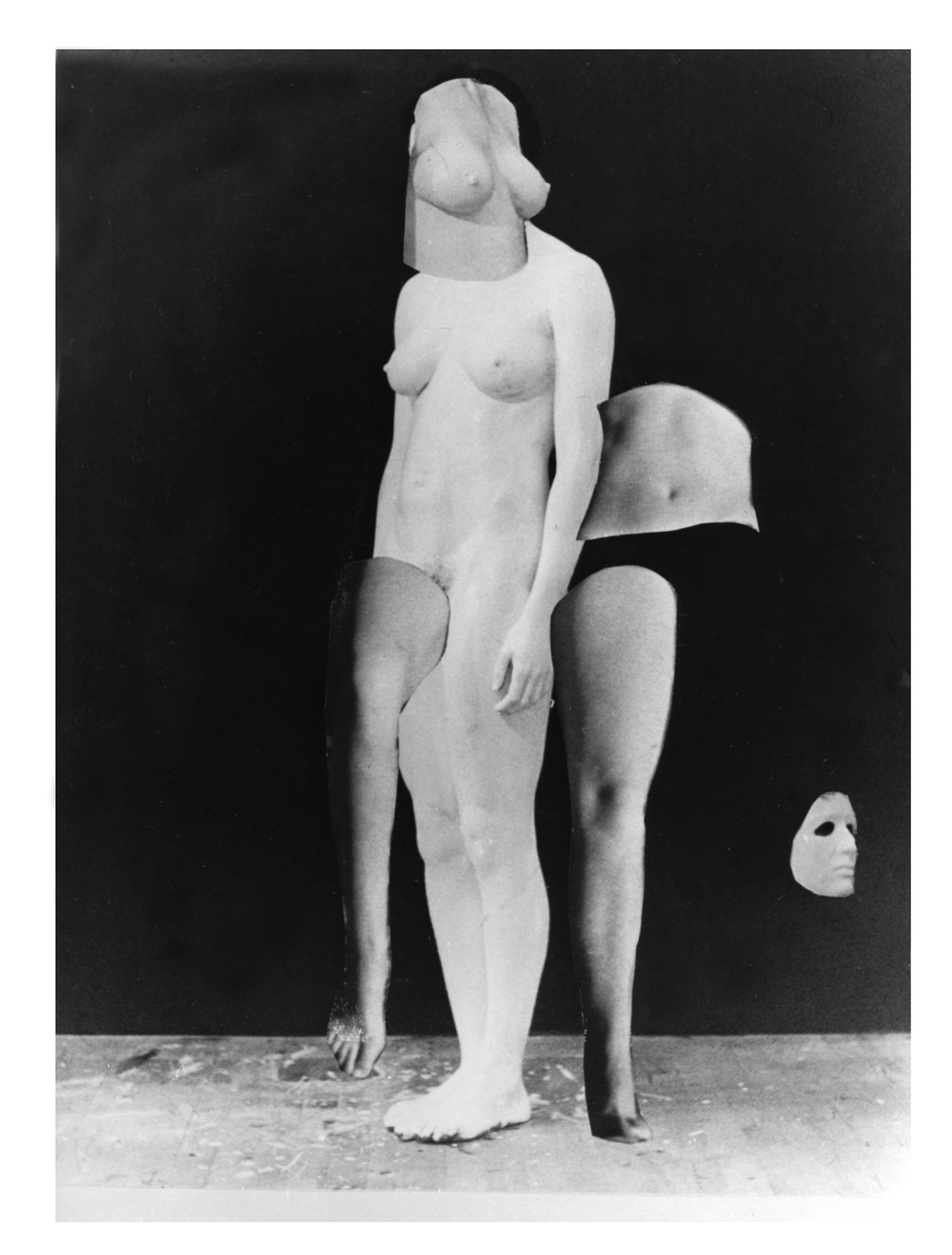

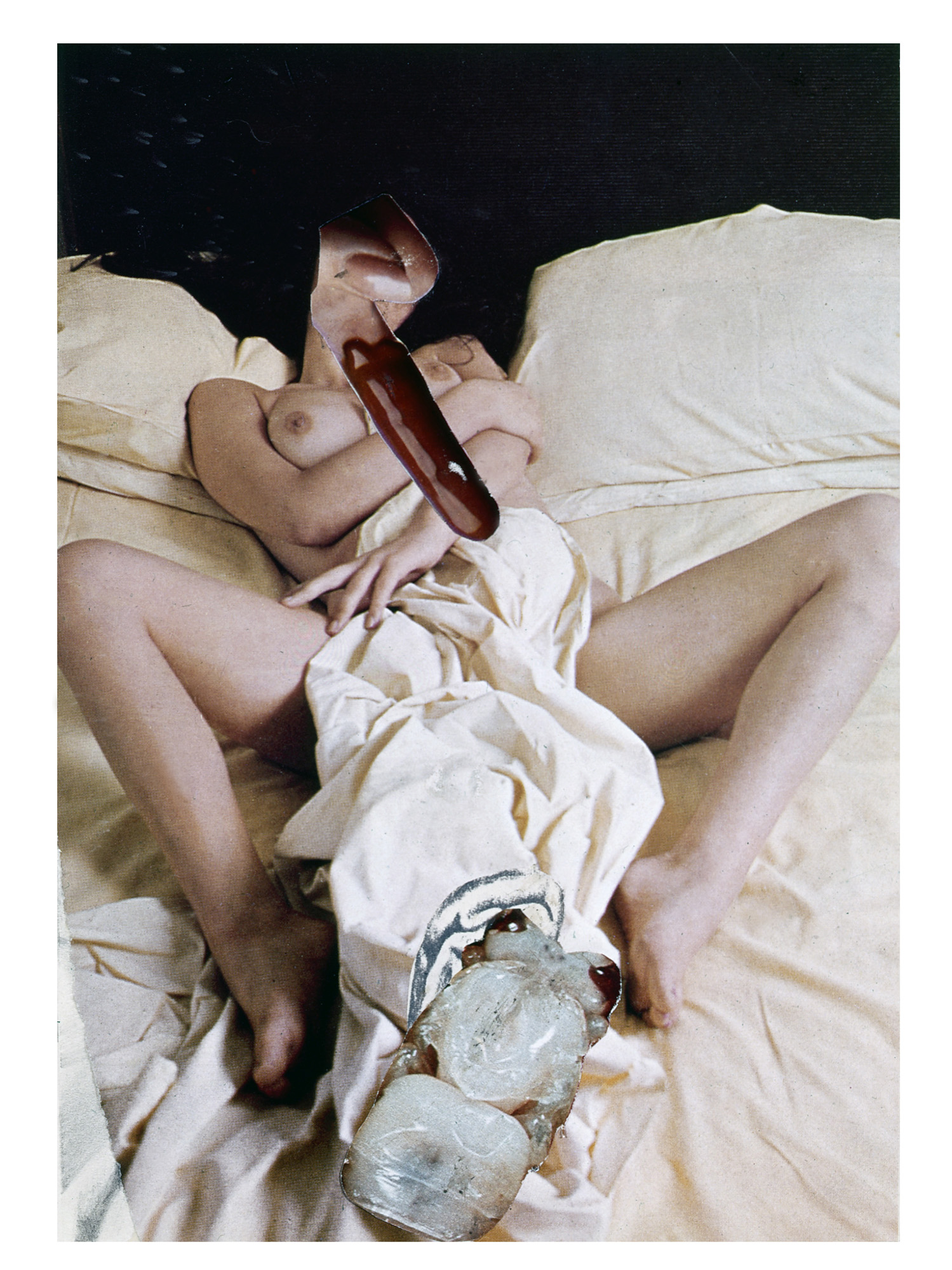

Her first publication, 50% The Visible Woman (1971), was influenced by Ernst’s surrealist approach to collage: “I had found a language that I could shape and form in my own unique way,” Slinger explains. A powerful reckoning with the psychic weight of being a woman in a man’s world, 50% The Visible Woman marries poetic writing with imagery of fantastical headless beings in violent, transformative scenarios like childbirth, disembowelment, and entrapment.

Collaboration and creative partnerships have been essential to Slinger’s development as an artist. At the start of the pandemic she began working with her partner Dhiren Dasu on an ongoing series of nude self-portraits, which show her trapped inside cabinets. Created while they were isolating, the digital photo-collages is fittingly titled My Body in a Box.

It reflects a continuation of her interest in the body not just as a subject but as a medium and even a raw material. “At the age of almost 75, I’m using my body as a muse again,” she says. “I want to break through this glass ceiling of ageism.” Slinger cites the importance of visibility as an older woman artist to share knowledge across the generational divide. “The wisdom of accumulated experience can’t be passed down to the next generation because the platforms simply aren’t there.”

“This was my attempt to express the dynamic of this newly found full-colour universe that I felt myself living in”

In 1970, she joined the newly established women’s feminist theatre troupe, Holocaust, led by prominent Welsh playwright Jane Arden. She would star in Holocaust’s play exploring the female psyche, A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets, and Witches in 1971, later adapted to the haunting and hallucinatory feature film, The Other Side of the Underneath (1973).

Slinger art-directed both productions, and even performed topless and on stilts. It was a transformative experience for the young artist, and an eye-opening practice in the potential, and pitfalls, of collaboration. The harrowing aftermath of the film, which is explored in Richard Kovitch’s recent documentary Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows (2015), fed into her creation of An Exorcism.

A year after her work with Holocaust, Slinger embarked upon her Bride’s Cake series, for which she created life casts of her body. Her stomach, breasts and mouth were transformed into wedding cakes and food platters, in an exploration of the relationship between women, eroticism, and food. The resulting exhibition, held at the Angela Flowers Gallery in 1973, has since proved a key moment in feminist art.

Slinger was unable to stage a live performance on the opening night due to restrictions set by the gallery. It was the first of a string of disappointments that left her increasingly disillusioned with the art world. “When you have big dreams, the inability to manifest them, the feeling of not being understood and appreciated is hard to swallow,” she says.

Twentieth Century Reconstruction, collage from 50% The Visible Woman, 8 x 10”, 1969, copyright Penny Slinger, courtesy Blum and Poe

She left Britain in 1979, never to return. “I felt the art scene was elitist. I wanted to reach out further,” she explains. “That’s also why I started to do books and publications.” She moved to New York and then the Caribbean for 14 years. Slinger set up the New World gallery in Anguilla and worked on an extensive series focused on the Arawak, an Indigenous people of South America and the Caribbean.

Her earlier discovery of Tantric art had been a key turning point. Walking into a now legendary exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1971, Slinger felt an immediate affinity: “There were bird-headed people and multi-armed beings, harking back to the kind of symbolism I’d been familiar with in surrealism, but here denoting something else.

“The tools of surrealism dredged the depths of the subconscious, and Tantra reached for the heights of the superconscious”

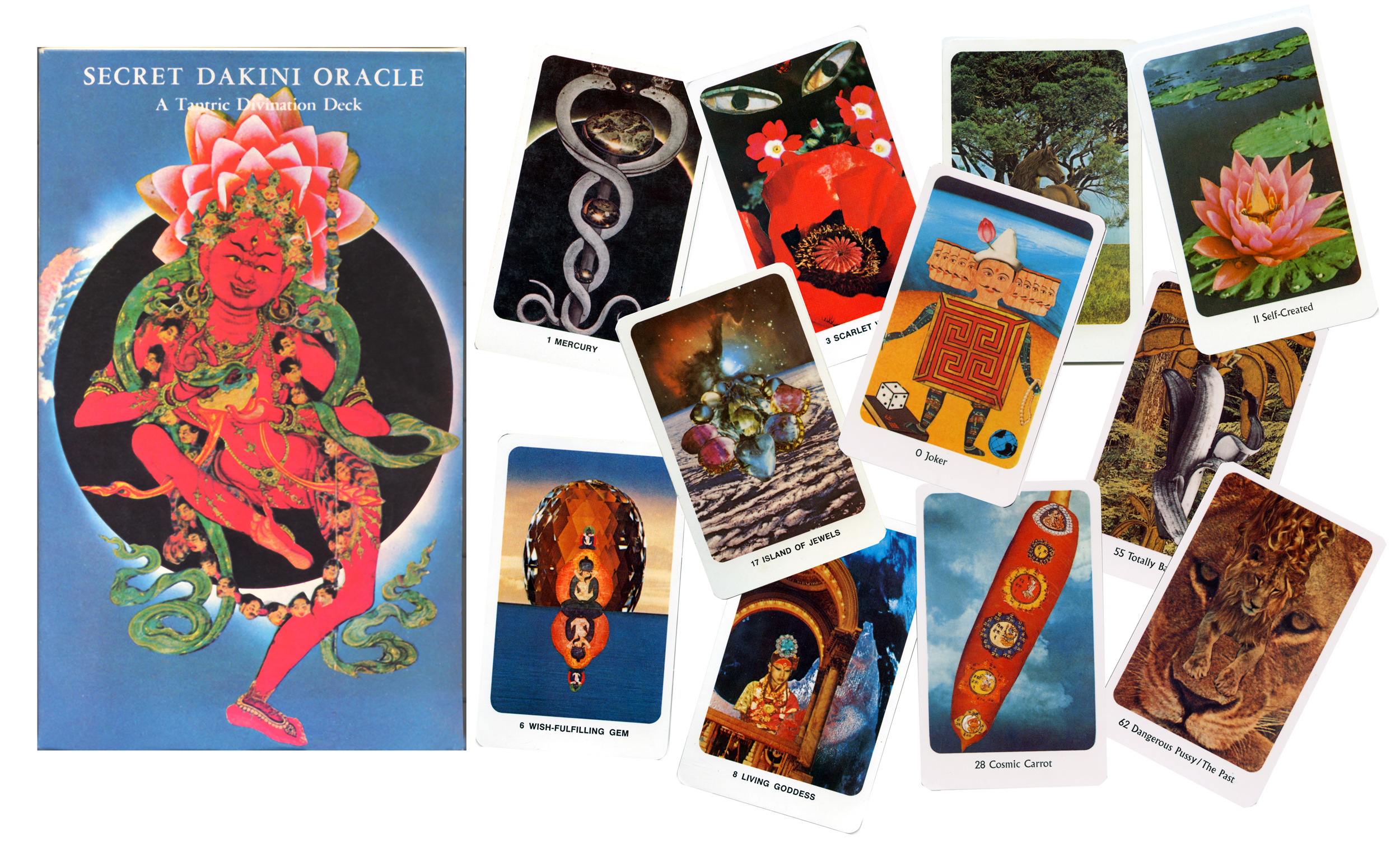

Slinger and her then-partner Tantric scholar Nik Douglas’s Mountain Ecstasy (1977) series and Secret Dakini Oracle deck (1976) are the perfect encapsulation of the transformative power of both collage and Tantra. An erotic cornucopia of polymorphous beings, tumescent genitalia, and stunning landscapes, Mountain Ecstasy was composed of found imagery collected on travels to India, Nepal, and Thailand. “This was my attempt to express the dynamic of this newly found full-colour universe that I felt myself living in,”she says. “It was saying that everything can be seen as part of this sensual dance of creation.”

In the mid-1990s, Slinger returned to the USA and lived in Boulder Creek, California with the microbiologist, Yogi and ‘Father of Spirulina’ Christopher Hills, who she married in 1996. A superfood pioneer, Hills set up the Goddess Temple for the practice of Goddess spirituality up in the Redwood forests of Boulder. Slinger hosted numerous multimedia events there and became the Temple’s guardian after Hills’ death.

“I suffered under the delusion that I could create my own career, that I could get into the art history books without the art world”

Swapping English dolls houses and country estates for Buddhist and Hindu temples, Slinger’s creative path may seem anything but linear, but she sees a clear through-line. “I see it as a curve: the tools of surrealism dredged the depths of the subconscious, and Tantra reached for the heights of the superconscious,” she explains For Slinger, the principles of Tantra extended the use of archetypal imagery in surrealism and offered a natural next step for her.

“For a number of years, I suffered under the delusion that I could create my own career, that I could get into the art history books without the art world,” Slinger reflects. But in 2009, people began to pay attention again, as part of a wave of new interest in the female artists of surrealism who had been excluded from the canon. She found herself included in significant group shows Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism at Manchester Art Gallery and The Dark Monarch: Magic and Modernity in British Art at Tate St Ives.

This interest in the spiritual aspect of Slinger’s work has grown gradually, in tandem with a growing engagement with esoteric art and the work of visionary female artists like Hilma af Klint. “It’s been much easier for people in the western world to understand the more psychologically based surrealist work,” she says, ruefully.

Back in the 1970s, Slinger put on several exhibitions merging the surrealist and spiritual collage work. “People didn’t get it. They were not ready to accept all that in one go.” It feels like they are ready now.

Sophia Satchell-Baeza is a writer and researcher with a focus on experimental and artist’s film, psychedelic art, and 1960s and 1970s countercultures

Brooke Olsen is an LA-based photographer