In New York, to coincide with the publication of a book by Steidldangin, Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s iconic Hustlers (1990–92) series – the basis of his first museum solo exhibition, held at MoMA in 1993 – went on display. In London, meanwhile, Zwirner presented his most recent collection, East of Eden, a series of large-scale images reflecting on “the collapse of everything” and “loss of innocence” triggered by the financial meltdown in the US in 2008. Tropes and set-ups familiar from his earlier work recur–there’s a pole dancer, theatrically heightened tableaux redolent of his celebrated fashion-based work for W magazine – but also some more unexpected elements: not least, evocative, widescreen Californian landscapes.

Sitting with his arms tightly crossed over his chest, diCorcia (known as ‘PL’ around the gallery) is a master of candid photography and proves a no less candid interviewee. We begin by talking about the London show, his first in the capital with Zwirner.

“It was definitely not an economic decision [to mount it],’ he says. ‘I don’t know if they make any money off a show like mine. One of the virtues of David Zwirner is that he does carry people for a long time. It may not seem like that because he’s turned into a bit of a juggernaut and taken on some very obvious, expensive artists. But from his inception, I guess 15 years ago, he’s had people that make no money. Eventually, maybe it does pay off. There are very few galleries these days that do that, certainly not of the size that he’s become.”

Why won’t your London show make money?

“To be honest, I don’t think Great Britain is the most sophisticated photographic market, they’re still a little bit stuck in the past. Although I think the work that I do has had a lot of attention paid to the way that it looks, it’s not decorative.”

So the US is a more sophisticated market for photography?

It’s a much bigger market. The East Coast, the West Coast, whatever’s in between.

What’s the difference between the UK and US?

For one thing, there are photography collectors [in the US], people who concentrate in that field. The economics of the art world, the speculative aspect, has come increasingly into play. The hysteria about the prices that people charge for things… is very often based on the idea that you can resell it for even more. In the photography world, with very few exceptions – and mostly the exceptions being those photographers who distance themselves from the word “photography”, like Cindy Sherman or Andreas Gursky or whatever – the speculative aspect of buying a work is not as prominent. Some art collectors buy work and it goes straight to a warehouse. That just doesn’t happen in the photography world.

DiCorcia is a master both of the faux-candid image (Hustlers, Heads) and of more obviously staged tableaux (his shoots for W). The pictures in East of Eden feel very deliberate; some of the titling is biblical. Is the machinery around his work becoming more elaborate?

‘Not really. I’ve always taken advantage of opportunities presented by other opportunities, in the sense that I might be doing some kind of commercial job and take advantage of the fact that I have a crew and a location. There are a couple of examples of that in this exhibition.’ For instance, Cain and Abel – showing two men, who may or may not be falling into a gay embrace on a bed, overseen by a naked Eve – was generated by a shoot for a book about Valentino for Rizzoli. ‘I didn’t pay to rent that hotel room. I just used it because I knew I had it.’

Though it’s given him significant opportunities for his own work in the past, he says that he no longer does much commercial work.

‘I tend to refuse to do editorial assignments any more because that’s become a joke. They’re kind of not interested in anything interesting. They don’t have any budgets. I don’t care what their name is, Elephant or Vogue, they generally have some sort of corporate entity that has the bottom line at the forefront of the ethos, so I don’t want to do that any more. The example of having worked for W for those 11 years – that world does not exist any more. Partly it’s a matter of personalities: who’s willing to say “OK, do this”, or who’s willing to go over budget, who’s willing to fly everybody over to some corner of the world and spend a week in order to produce – well, as you probably know, in magazines there’s a relationship between budget and how many pages it’s going to make… I never had anyone during that period tell me anything except that we gotta get the Armani dress in here somewhere, because he’s the biggest fashion advertiser in the world. But other than that they just let you do what you want. And if you said you wanted to shoot in the opera house, they’d figure out a way to do it. And you didn’t have to spend all day in the opera house shooting the entire story, you could just go and do one picture. That never happens any more.’

East of Eden is about a loss of innocence and disillusionment; it sounds as though he has experienced that disillusionment personally.

‘I was as affected by things that I’m referring to when I talk about disillusionment as anyone else in the United States,’ he says. ‘The bottom dropped out of a lot of things. The last story I did for W, for instance, was done in 2008.’ That was also about the time he joined David Zwirner. There was, he says, a feeling of ‘what next?’, so he did what he has often done in the past: ‘I tend to try to develop a conceptual background, sometimes simplistic, as a jumping-off point for what I’m going to do. Sometimes it retains itself throughout the series, sometimes it just gets you out the door.’ The jumping-off point this time was the Book of Genesis, although he’s not sure that that’s apparent in a lot of the final images. ‘In this case I’m willing to bet that most people need a press release to work out what that series is about,’ he says.

The prints are large-scale – but of course diCorcia is one of the seminal figures in the late twentieth-century shift to Big Photography. ‘When the Düsseldorf School broke out, everything seemed tiny. They very deliberately tried to disassociate themselves with photography through scale… I don’t think the size of my prints increased simply for that purpose. If you think about it, one of the last projects I did was the Polaroids [Roids, shown at Sprüth Magers in London in 2010] – they’re tiny. There just happens to be a lot of them. I think this whole size thing came because photographs and paintings were being shown in the same room and it’s really hard: I think photography suffers a lot when you put it in the same room with paintings. It loses its attraction, its whatever – it’s almost impossible to suspend disbelief somehow.’

‘There’s no commercial consideration,’ he says of his work. ‘I don’t go: This one’s going to be a big seller, or anything like that. And, to be honest, the ones that do actually wind up being big sellers are rarely my favourite. They always seem a little bit oversimplified. In this show I would say the two dogs watching pornography is not the photograph I’m most proud of because it’s an illustration basically, and illustrations are always by their nature clipped in their possibilities of meaning. I could say that about the Hustlers too. The most popular one by far is the one where this drag queen mimics Marilyn Monroe. Everybody loves that one. It’s so obvious.’

Hustlers, of course, marked diCorcia’s arrival in the major league. The project was funded by a National Endowment for the Arts bursary (along with Guggenheim Foundation money) and was made against the background of the early 90s US ‘Culture Wars’, a post-AIDS pitting of conservatives against progressives that shone particular light on federal funding for the arts: 1989, the year diCorcia received his grant, marked the controversy over plans to show Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Perfect Moment at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC with NEA support.

Was Hustlers – a series of staged portraits of male prostitutes in LA, captioned with their names, hometown, age and (most controversially) the amount of money they charged – a deliberate shot fired in the Culture Wars?

‘I don’t know that it was conscious,’ says diCorcia. ‘I lived in New York City in a world which was, let’s say, very inclusive… My brother was gay. I would say 50 per cent of the people I knew were, both men and women.’ Though shot on the opposite coast, Hustlers grew naturally out of that context. ‘The idea that these guys were commodities and objectified has a direct relationship to paying them, and I was using the government’s money to pay them. I don’t know if that was a eureka moment or I carefully planned it out, but once it occurred to me it seemed so kind of perfect I just went ahead with it.’ He doesn’t recall the right-wing lobby reacting to the images, which managed to enter the artistic mainstream – after all, they were shown at MoMA. Rather: ‘The questions at that time were: why did you choose just men? Why don’t we ever see anything of their personal life? How come there’s no depiction of what they do – which would have been the normal photojournalistic approach to that.’

The reaction against ‘normal photojournalism’ was the starting point for Hustlers, then: ‘photojournalism is just telling you what you already know, it’s fulfilling your expectations, and that’s fine if it serves a purpose. But as an art form it doesn’t really have much depth. As a photographer with photojournalism as the predominant mode of photography when I started, I was trying to change out. I guess the point was, you can know a lot about life through photography but you’re probably not learning very much about the particular subject. So there couldn’t be a better way to do that than with people who portray themselves as something that they’re not.’

How would you situate yourself in terms of the photographic tradition? With someone like Larry Clark, for instance…?

‘The usual question is more like: Do you have a fascination with the underbelly? [Laughs.] And I would say: Yes, maybe. Larry Clark doesn’t go and photograph suburban youth. Of course, everyone knows that I went to school with Nan Goldin and David Armstrong and people who have a reputation that is based upon what people assume to be their lifestyle. I’ve never wanted to make work that people would assume had something to do with me, because I feel like that’s always the case. Artists’ work always reflects them in some way or another. To have it actually be about them, as with Larry Clark and Nan, is not interesting to me.’

Though you sometimes use your own family in your work.

‘Yeah, but you wouldn’t know that they’re members of my own family. It’s easy to use members of your own family, they’re available.’

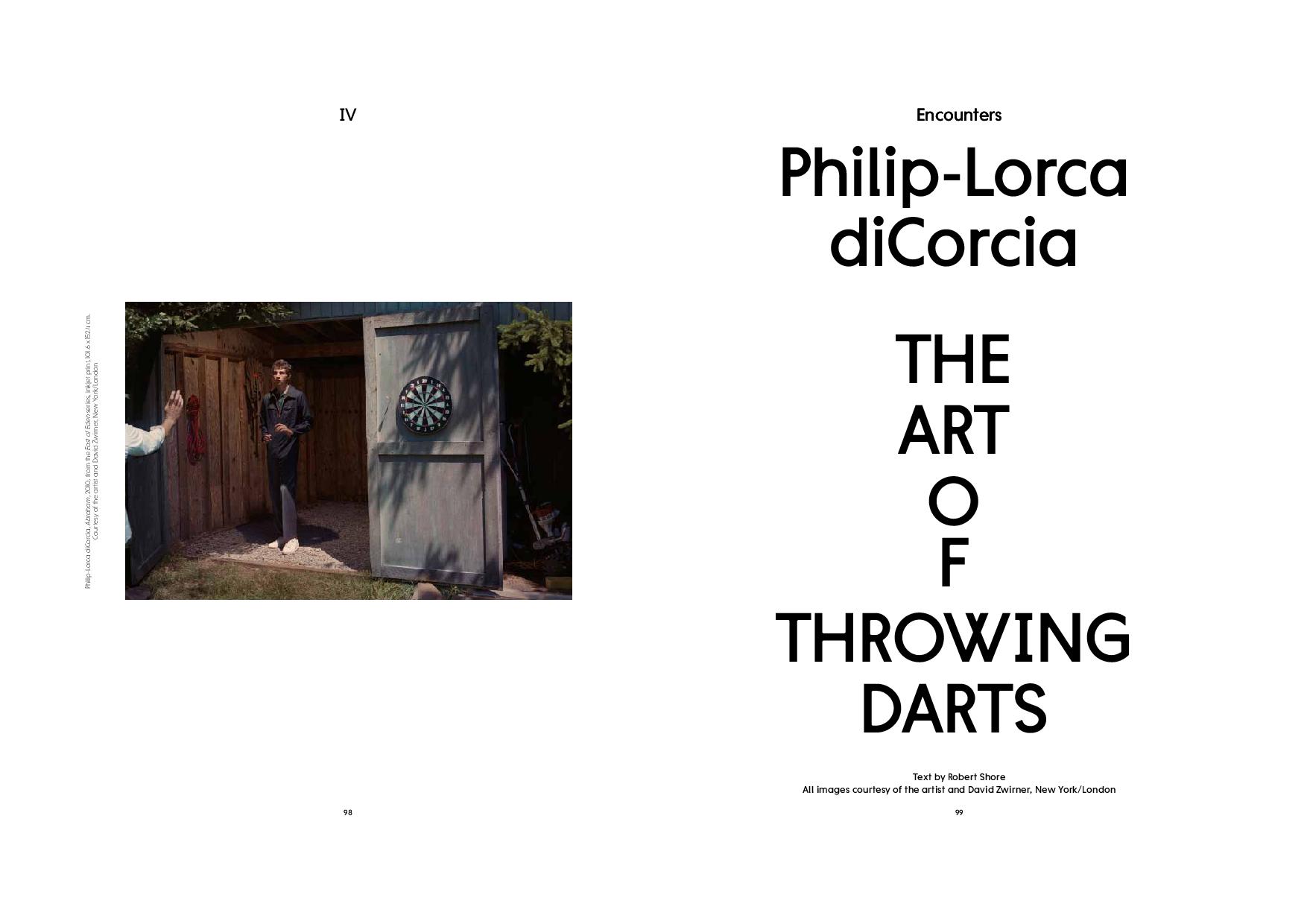

It’s your own son you’re throwing a dart at in the Abraham shot in East of Eden. How did he feel about that?

‘He’s used to being photographed – not just by me, but by Nan, for instance. And he didn’t mind at all. I’m not sure I explained to him exactly what I was doing [laughs], but of course throwing darts at your own son is…’ He pauses. ‘I didn’t plan to do that, to be honest. Some of the best photographs are the ones where you’ve sort of got a vague idea in your mind and head towards it and then get diverted into something that you didn’t expect and it turns out to be better.’

Though they may not know quite how the image will turn out, most of diCorcia’s subjects know they are being photographed. He famously departed from this practice for his Heads series, shot in Times Square in Manhattan between 1999 and 2001 using strobe lighting. One of the unsuspecting subjects, Erno Nussenzweig, was very displeased that his image had been used in this way – although most critics found the works unusually and existentially revealing – and sued. ‘He had his religious reasons. But, quite frankly, I think $1.6 million, which is what they sued me for, was also sort of a motivation,’ reflects diCorcia now. ‘The way that the litigation system for those things in the United States works is that it costs so much to defend yourself, you generally make a settlement because you’re going to pay your lawyer that much anyway. I had a lawyer who worked pro bono and he did it because it was a constitutional rights issue… But the actual law that they [Nussenzweig’s team] invoked was that you cannot use a person’s image in commerce or advertising without their permission. So they were claiming that an art gallery is commerce and the catalogue was advertising – and, you know, in a way I don’t disagree with that. Quite frankly, if somebody did the same thing to me I wouldn’t be happy. [But] I wouldn’t sue them. How art, which is very clearly about money these days, slips the noose by being “freedom of expression” was a lot of what this court case was about.’ As the judge said: ‘[F]irst [A]mendment protection of art is not limited to only starving artists.’

DiCorcia’s initial art education happened in Boston. ‘When I got out I didn’t have a grand plan,’ he says – the lack of a grand plan seemingly being something of a motif in his professional life. There was a recession on at the time, so he opted to go to graduate school and ended up at Yale, in the department founded by Walker Evans. ‘It had a very particular point of view,’ he says. ‘Half the people that were there when I went for my first interview took pictures of rocks and ferns with black-and-white large-format cameras. I actually think I wouldn’t have got in two years later. It was in a transitional period. Walker Evans had just died [in 1975] and they were looking for a replacement, so that was the way it went. And now I teach there, and it’s a completely different place.’

At the walk-through at the gallery a couple of days earlier, someone had suggested that, actually, diCorcia no longer teaches there because he’s quit. Is that true, or is the matter still up in the air?

‘No, I did [quit]. I’m not sure they believed me,’ he says. ‘There were probably some petty reasons. But it’s also that, in order to be good at that, to feel like you’re not just sitting up there bullshitting [your students], you have to have some relationship or enthusiasm about the work, and increasingly the work that comes out of photography as an art form has no relationship to any actualities.’ He says that he sees a significant shift in the art being produced, involving a level of abstraction that he seemingly finds it hard to engage with. ‘The work is very different… I started out using photography as a kind of conceptual tool, as was in the 70s common usage, and that’s how I got into it. And now strangely it’s come full circle, it’s a conceptual tool. I was interested in it then, I’m not interested in it now. Having to critique people’s work is not something I take lightly because they don’t take it lightly. Your words can be quite disturbing to somebody who’s spent a lot of effort and emotional currency in doing something… I don’t just say “I don’t like it”, I have to explain why, and it’s become more and more difficult to come up with the energy to be bothered with that.’

At that walk-through a few days before he’d also made it clear that he doesn’t care for the impact the Canon 5D has been having on his students’ work. Why does he hate the little 35mm still-and-moving-image marvel so much?

‘I don’t hate it, it’s just so prominent. Everyone has one. It’s too complicated for me,’ he shrugs. He still shoots using analogue film. The negatives are then scanned, which allows for digital manipulations such as the removal of the bellybutton of the Eve figure in Cain and Abel (Eve was generated from Adam’s rib so there would have been no umbilical cord to tie off).

He says he doesn’t like the way digital cameras render the world. The profusion of images that goes with filmless technology also bothers him.

‘Although you can get a contact sheet made from what you do – I don’t know, there’s something about having so many images around,’ he says. ‘When people shoot digitally, you never have to change the film. Instead of 150 images, you wind up with 2,000. It’s ridiculous. I might have considered using large-format digital, which has an easier capacity to control the things I like to control – what’s in focus, what’s not in focus. That’s almost impossible with 35mm digital. It’s boring to even explain why but it’s true. And the larger ones are incredibly expensive and outmoded in two years.’

DiCorcia has started attending art fairs – not many, perhaps (‘I’ve been to half a dozen in my entire career’), but all since he moved to his new gallery.

‘Almost all of it was intentionally in support of David Zwirner. I never went to art fairs before. Art fairs in their prominence and their commercial impact basically have come to dominate and I just wanted to help these people because they’re trying to help me: by showing up, by going to the dinner, by doing all of that stuff, like being a player and not trying to seem as if I’m above the fray. But I don’t find art fairs interesting… It’s such a blatant display of commerce. And also you get to see all the customers and that’s a kind of rude awakening as well.’

Has the kind of person who buys art changed so very much? ‘I didn’t have to see it [before],’ he deadpans. Art education is becoming ever more popular, and the art world ever more globalized. ‘I went to graduate school at a time when going to graduate school as a pathway to an art career was a waste of time,’ says diCorcia. ‘Now, in every corner of the world, there are artists that are no different in terms of their training and their knowledge than anyone in New York or LA. And once certain trends within art get established, they get played out all over the world, not just in the centres, the traditional five cities or wherever.’

Is that an interesting phenomenon? Are the variations interesting? ‘Well, it makes it harder to remember anybody’s name.’