“I never put something on Instagram because I think it’s shocking or funny to be chopping a snake up; I just think it’s interesting to show what I’m doing in the studio.” I’m speaking with British artist Polly Morgan

in her South London workspace, which is housed in the basement of her home: a converted pub in Peckham. There are two freezers full of animals, taking the form of disembodied chunks and whole creatures, stuffed so close together they almost appear vacuum packed. The walls are loaded with saws and tools for butchering and re-forming the many bodies that inhabit her works. “I’ve taken what I think of as really beautiful images of the skinning process, and instantly they get blocked, and you just think about all those food bloggers who are photographing steaks on their plate and think: why? The minute you can see an eyeball or anything, people get hysterical. If you’re a meat-eater or you’re wearing leather shoes, you’re in a glasshouse; you can’t start throwing stones. It’s your duty to understand where it comes from.”

Morgan’s work initially boomed before social media had really hit its stride, when many artists are embracing the platform as a means to provide more open access to their process behind the scenes. Conversations around the source of our food have changed since she started making work too, such as a rise in veganism, and with it more discussion around the hypocrisy that surrounds our differing relationship to animals as pets, consumables, clothing and art. Morgan points out that although not many people have a problem with images of cooked meat on the platform, an image of chopped up snakes that she posted was not so well received, although they had in fact died of natural causes. As she points out, this is a common standard of the taxidermy world, though one she is often prompted to confirm.

The artist uses her platform to show very openly and honestly behind the scenes, with practical videos and images of the butchery and skinning process. She doesn’t just present perfected finished pieces; we see the source and the occasionally shudder-inducing nature of how they came to be. She gladly discusses the reasons why we might respond in this extreme manner to her work. When we meet, her studio mate Robert Cooper, another British artist who works with animals as a material, has just felt the wrath of Instagram users. The provenance of two found images he posted, one of a live deer in the back of a car and one of a dead deer in a jar, were misunderstood to have been taken by him: the first apparently showing a kidnap, the second, the evidence of a brutal murder.

“The minute you can see an eyeball or anything, people get hysterical”

Both artists tell me about the responses they have received online, from Instagram users who often jump to conclusions that they then don’t wish to be proved wrong about. The two have since set up a YouTube video series, which shows even more of their working method: in the first minute of episode one, we see a snake being diced up with a circular saw. The videos also offer a comical insight into their very hands-on working practice—the tests and moulds that go wrong, as well as those that lead to exciting results.

While Morgan has refused to let online offence affect her practice and the way she shares it, she has moved away from the more figurative presentation of mammals and birds that first raised her profile. Now, she is embracing something more abstract and architectural. “Taking an animal and making it look like that animal, people come to it with so much baggage already,” she tells me. “They’re not really looking at the work as a whole, they’re responding to it as a ‘cute’ squirrel or a ‘repulsive’ rat. In the beginning I found it quite a fun challenge to work with this. One of my first works was of a rat, and a lot of people reacted quite well to it and thought it was beautiful.”

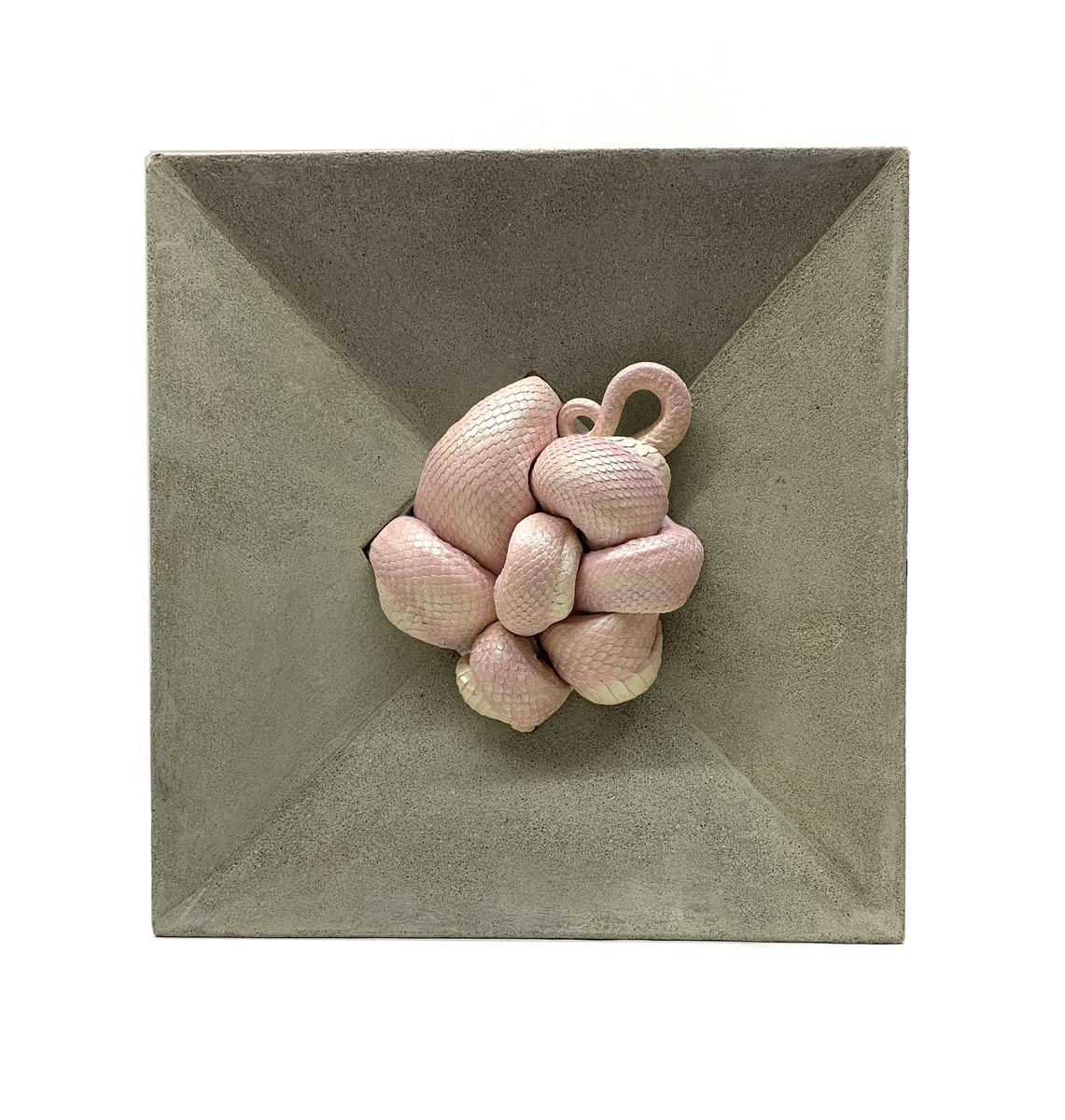

But while her works now include recognizable elements of animals—the distinctive markings of snakeskin, or the muscular curves of a serpent’s body—they appear more as a malleable material than as explicit subject matter. When I visit the studio, Morgan shows me a selection of pieces that reference brutalist architecture, grey blocks with tight bunches of snakes’ bodies spilling out the top. “There were a lot of elements in the works with the birds that gave a them a kind of narrative,” she tells me. “It became a lot more abstract when I started working with the snakes. The first works with snakes looked like modernist, abstract sculptures on plinths and blocks of marble. Those were kind of the bridge. I wasn’t enjoying my work anymore. I wanted to be able to manipulate the bodies and the forms more, but when you do that with a mammal or a bird it looks kind of steampunk. They can look a bit gimmicky.”

The snake works take a further step away from the source animal than Morgan’s previous sculptures—most are casts of bodies (slices of snake fill the artist’s freezer for regular reuse) and she often recreates the skin on top of these. The heads are rarely used. “There is a visceral reaction and that’s why I don’t use the heads,” she tells me. “I don’t want it to be a confrontational thing. It represents the spillage of flesh, or the spillage of anything. I see the concrete as being corset-like, trying to contain, and the snakes trying to spill out. For me they’re representative.”

“I don’t want it to be a confrontational thing. It represents the spillage of flesh”

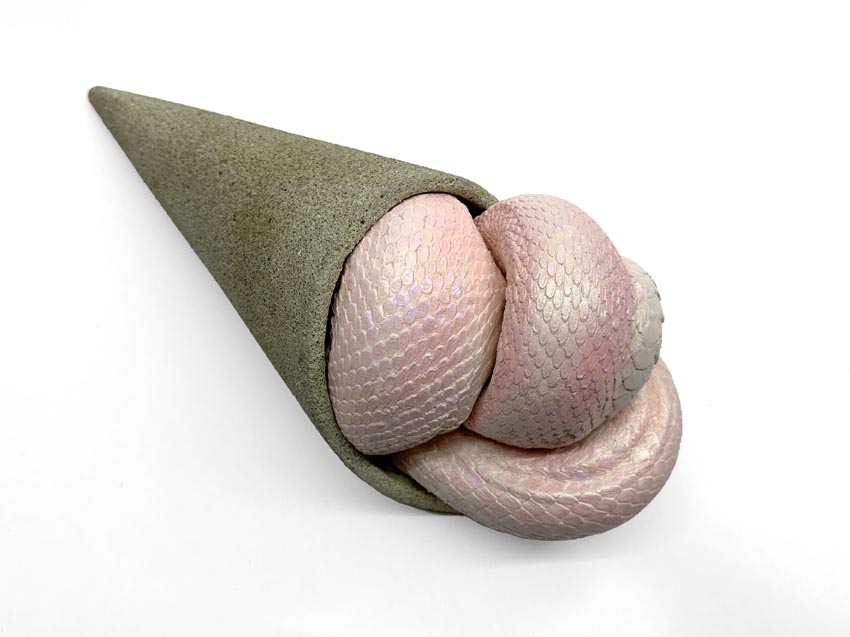

For the more architectural forms, Morgan takes inspiration from buildings as well as items that “constrict and contain the body”, such as shoes. She draws these on the architectural programme SketchUp. Despite the evil associations we have with snakes, there is a brightness and occasional humour to the work (some smaller pieces show snake bodies squeezing into ice cream cones), which sits at odds with the typically dark associations we have with taxidermy as a technique.

Work in progress, 2019-2020

“People instantly assume that my work is about death or that it’s morbid, but death is simply a logistical thing for me,” Morgan tells me. “I obviously cannot work with a living animal, so I have to wait for it to be dead to be able to work with the skin or the body. I’m not celebrating death; I hate death. I’m not scared of it, I would just rather not yet!” In the end, she hopes for the use of animals within art to be seen in much broader terms than the associations we currently bring to the form.

“It was an untapped medium when I started,” she tells me. “There is such a breadth and spectrum that things are placed on with mediums like sculpture or painting, from figurative to abstract and back again. With taxidermy there never really was that—I suppose Damien Hirst had that very clinical, medical style, which definitely started it off. But it’s a challenge to take it as far from the stuffy museum type of display as possible. I think people struggle to see something as an art that has so traditionally been a craft.”