It’s unmistakable at fifty paces: the perfectly coiffed woman in seductive peril or the hard-boiled man in a trench coat surrounded by lurid scream-quotes promising lust and death. “Pulp” is a schlocky, kitsch and fun aesthetic that is still being explored by contemporary artists, who are finding their own uses for the particular balance of chaotic violence and chrome-plated, red-lipped, nicotine-stained beauty. The style has a long history, stretching back through film, pop art and comic books to the biscuit-box kitsch of Victorian fantasy, and its eager adoption by advertisers and illustrators alike.

It has (in many cases deservedly) had a bad rap for being misogynistic, decorative, camp yet homophobic and just plain simplistic. In the nineties, artists like Richard Prince and the Connor Brothers exploited the aesthetic for its digestibility and commercial potential, doing nothing to critique its often woefully reductive tendencies. The pulp aesthetic was in danger of only being associated with the kind of “quirky” canvases available in your local ArtRepublic, or tragically risqué birthday cards.

The aesthetic associated with pulp illustrations has, however, also informed the creation of some incredibly important art and media, from Lichtenstein’s morally ambivalent comic book panels to Hopper’s quiet, noir-tinged snapshots, to Tarantino’s ubiquitous masterpiece. Works like these play with the inextricable link between pulp aesthetics and storytelling. The visual shorthand of “pulp” images was refined and perfected in advertising, comics and on the covers of Penny Dreadfuls, shaping the visual language of popular storytelling until it became inextricably entwined with narrative illustration.

Hopper’s works, filled with the heat of summer; the glare of electric lights at night; and the loneliness of an atomized, modernized society, pares back the demanding tone of a pulp book cover—they don’t scream “She went too far—too often” or “Their loneliness drove them into each other’s arms”, giving away the story before you even open the page, but they do convey an unmistakable sense that there is one, somewhere, that the simple glimpse of a moment can’t show you.

“‘Pulp’ is a schlocky, kitsch and fun aesthetic that is still being explored by contemporary artists”

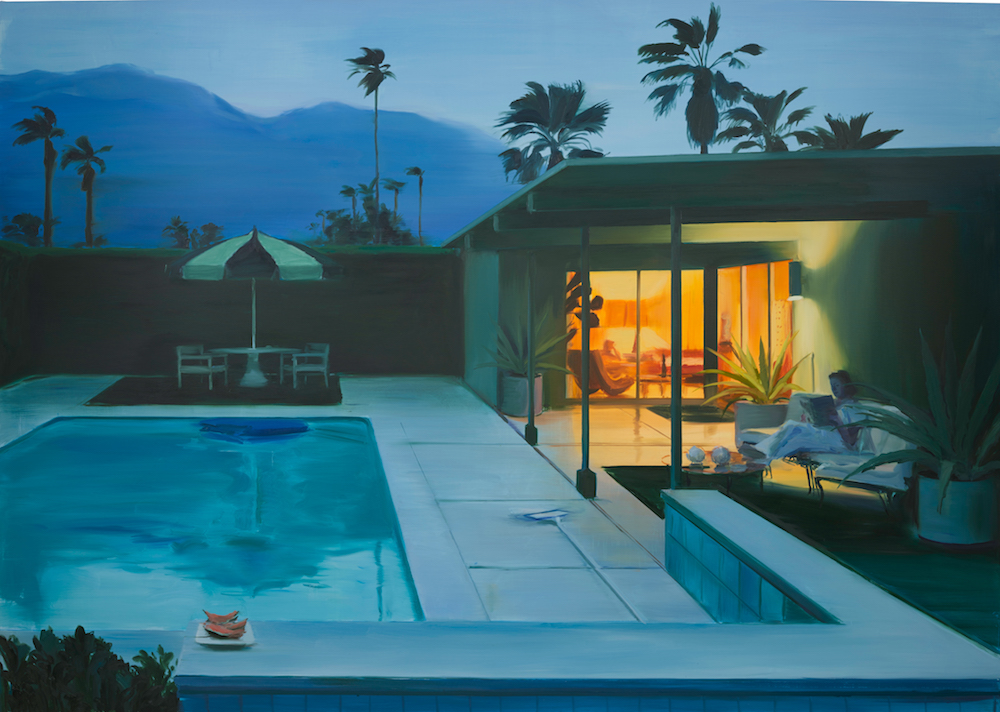

Caroline Walker, Desert Modern, 2016. Courtesy Grimm Amsterdam, New York. Photo by Peter Mallet

Often a top-note of pulp is invoked to explicitly deny the viewer the satisfaction of a complete story. Caroline Walker’s quietly observant oil paintings, often of nighttime scenes and composed at a distance that suggests voyeurism, focus on the intimate loneliness of the figures she paints. These figures, often domestic or service workers, are not pitied or valorised by the pictures—there’s simply a strong sense of a vast inner life, a whole individual identity and story, from which both the artist and the viewer are shut out.

These stories don’t have the full blown melodrama of pulp, or even the tinge of repressed violence or sexuality present in many of Hopper’s works, but the simple act of painting them highlights their existence, and creates a sense of curiosity about the still-vibrant lives of these human beings, however mundane.

More dramatic and more enigmatic, yet still playing with ideas of the inner lives and unique narratives of individuals, is the work of Alex Prager, whose films and photographs often feature an unknowable yet familiar protagonist in a crowd. The costumes and set dressings Prager pulls together create a postmodern timelessness, which relies heavily on the streamlined visual vocabulary of pulp—perfected in popular visual culture over decades to convey vast amounts of information about character and role.

In Prager’s works however, this is flipped on its head to create a dreamlike quality—everything is familiar but it’s not actually conveying much (if any) information. The unknowable inner life of the protagonist in their mysterious story is in sustained tension with the undeniable familiarity of the images. It evokes a sense of being isolated in your own individuality, feeling like you’re the protagonist in a story which should make sense, but is ultimately chaotic.

“The feminist appropriation of pulp aesthetics isn’t unique to contemporary art”

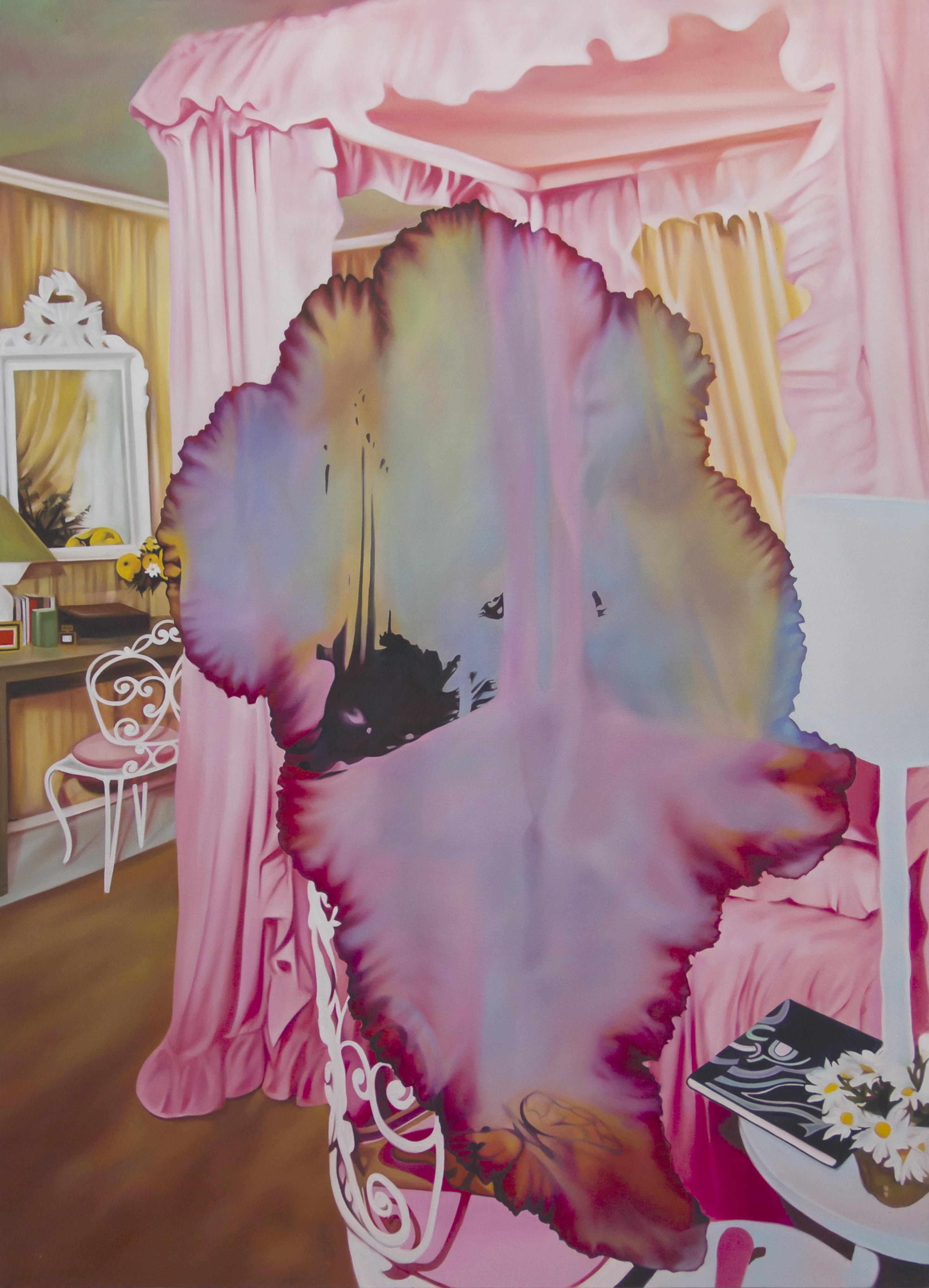

The sense that spaces can be settings for stories or events is a strong underlying element in Ariana Papademetropoulos’s water paintings. Made on a vast scale from old photographs, these works employ the colour palette of an old, cheaply printed pulp novel cover with water damage—the inks running and merging, becoming more vivid and more washed out, distorting the image underneath. These paintings of kitsch and over-the-top retro interiors are striking for their emptiness. They carry and impression of the just-vacated; the sigh a room lets out when everyone leaves. Rather than wondering about the inner life of an anonymous protagonist, the viewer wonders what these rooms have seen, what heightened scenes (to match the lurid colours) took place in these spaces?

The idea that “walls have ears” is echoed in another pulpy standby—sensationalist voyeurism. Many of the most successful pulp novels were tell-all exposes, the crimes of passion, the dirty secrets of affairs and blackmail and, of course, the scandalous lives of homosexuals. Although the content-starved queer community had a complex relationship with these books, the stories were fundamentally exploitative. The highly sexualized women on the covers of pulp novels were tantalizingly “unavailable” to men, even as the way they were drawn lured them in.

Flipping this unhealthy patriarchal dynamic on its head, Jenna Gribbon’s paintings are unabashedly queer, reclaiming the female gaze and owning the right to find and render women attractive. She uses a pulp-infused painterly style to revel in the sensual potential of her subjects the way the old illustrators did, but from an entirely different perspective.

“The highly sexualized women on the covers of pulp novels were tantalisingly ‘unavailable’ to men, even as the way they were drawn lured them in”

The relationship between pulp and film and feminism is also a theme in the work of artists like Cindy Sherman, who play with the idea of the female protagonist, and of the artist/individual as the main character in a story. Those works, like Prager’s, often convey a sense of anxiety and unease with the narrative in which the protagonist finds themselves. And the feminist appropriation of pulp aesthetics isn’t unique to contemporary art—designers across television, fashion and music are also still drawn to the artificially heightened qualities of pulp visuals. Netflix’s teen-noir Riverdale, for instance, has built contemporary feminist and queer perspectives into its foundations, but also features capes, funeral-specific cheerleading uniforms and a lot of red lipstick. They tend to be melodramatic in the extreme, and set their characters adrift in a menacing and inexplicably chaotic reality.

We live in a culture which encourages us to project the illusion that we are protagonists in a coherent, well-written, and preferably entertaining story. But reality isn’t succinct and linear, and it certainly doesn’t always have a happy ending. The conflict inherent in the noir-burlesque aesthetic of pulp illustrations, between the idealized beauty and the a-moral darkness framing it, affirms our suspicions that we live in a world which tends towards the kitsch, the cruel and the melodramatic. It doesn’t deny our desire to live in a story, but it brings the ultimately artificial nature of narrative to the fore. For women, the power to construct and control our own narratives is still radical, but evoking the knowing artifice of pulp paradoxically allows the artists to do so while keeping one foot in imperfect, entropic reality.