I’m standing outside a room-sized glass box, my nose pressed against the red-splattered walls, watching a horror show unfold in front of me. Inside this panelled box, whose walls are elevated far above head height, a large robotic beast is mopping a thick and bloody liquid substance into a satisfying circular pool around its base. It slowly rotates, capturing liquid that is spreading back out towards the edges of the box and dragging it back in, leaving smears clotted along the floor. Five minutes later, the machine bursts into a crazed dance, waving its mop-ended arm around high above it, splattering red liquid as it goes (in total, the life-like machine has thirty-two programmed settings, including “ass shake” and “scratch an itch”). Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself is horrible, crass and mesmerizing, drawing both eye rolls and longing, dead-eyed gazes from the crowds at the 58th Venice Biennale.

This work sits in the Biennale’s curated exhibition May You Live in Interesting Times, in the half of the show that is housed at the Giardini. Over in the Arsenale the artist duo has another work, a large chair that looks as though it is carved from marble or ice (it is a mock-up of the marble chair at Lincoln’s memorial). A hose protrudes from the centre of it, every so often blasting out a ferocious jet of air that sends it into a snake-like frenzy, whipping loudly against the box it sits within, leaving large scratches on the walls. Occasionally it shoots out over the top and snaps at viewers who shriek and jump back before quickly composing themselves and returning to chin-stroking silence. The phallic connotations are unavoidable.

Perhaps it’s the miserable hour-long walk in the rain that I took to get to the Arsenale (wrong boat; the perils of Venice) or perhaps it’s the horror of the latest Game of Thrones episode that still hangs in my mind (a surprisingly popular topic at art dinners the world over), but I find myself drawn to the dark and the horrible at this Biennale. Without directly alluding to any singular horror or political moment in particular, these two works capture an uncomfortable meeting point of science and torture—the boxes call to mind cages or observation boxes. The frenzied energy inside both boxes feels animalistic. Do these creature-like forms have evil intent, or are they innocents being studied? Both the bright lights that hover above the blood-scooper in the Giardini and the gloomy warehouse space that houses the chair in the Arsenale play into this—dark corners and interrogation lights. The works hint at mass deaths, abuses of power, machines overtaking our fleshy mortal forms.

- Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2009. MS Gate which swings side to side and breaks the walls. 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times. Francesco Galli, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Also in the Giardini show, is Shilpa Gupta’s Untitled, in which a heavy automated gate swings back and forth through 180 degrees, smashing rhythmically into the wall to its left and right. Lumps of plaster have smashed out of the wall around it, and each predictable jolt and smash brings about a split second tensing of my body. The work evokes ideas of security and division, things being locked both in and out. After viewing this and Can’t Help Myself in quick succession, in my heightened nervous state I presume that the eruption of piercing screams behind me is part of yet another evil work. It is, in fact, just a baby crying.

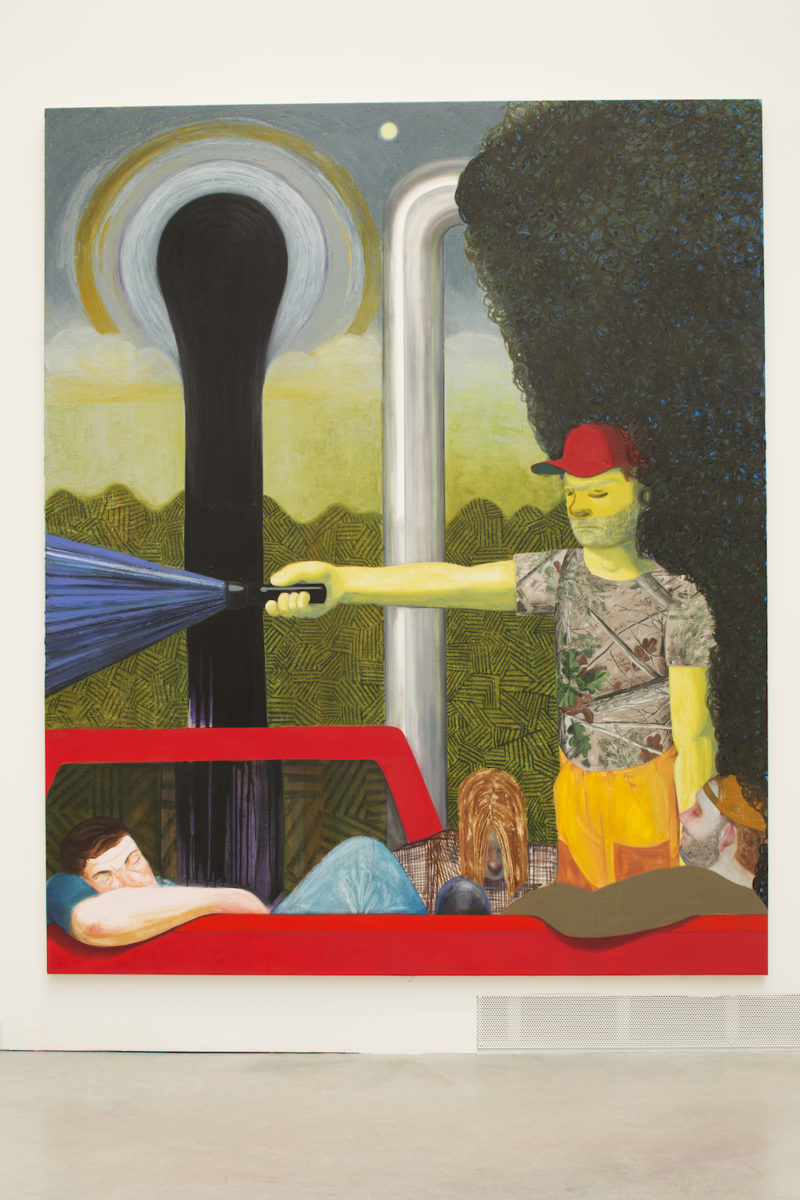

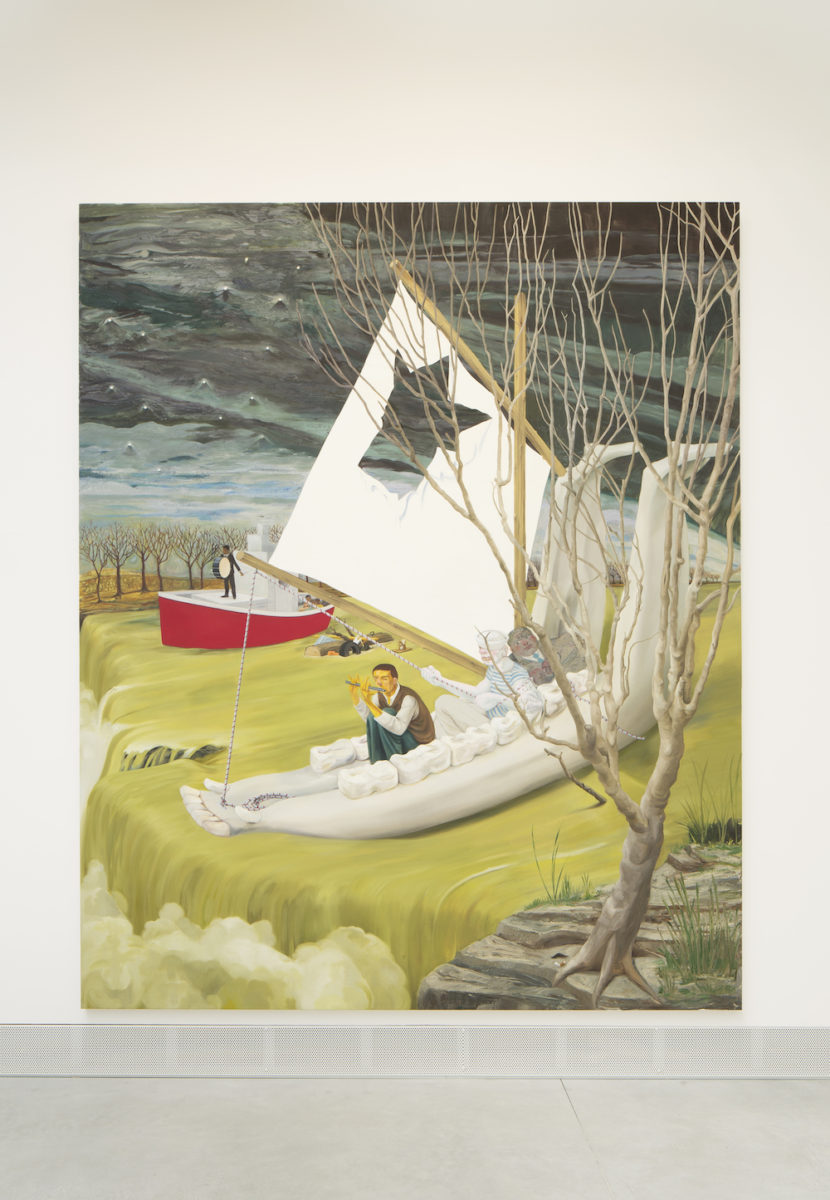

- Nicole Eisenman, Various works, 2014-2017. Oil on canvas. 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

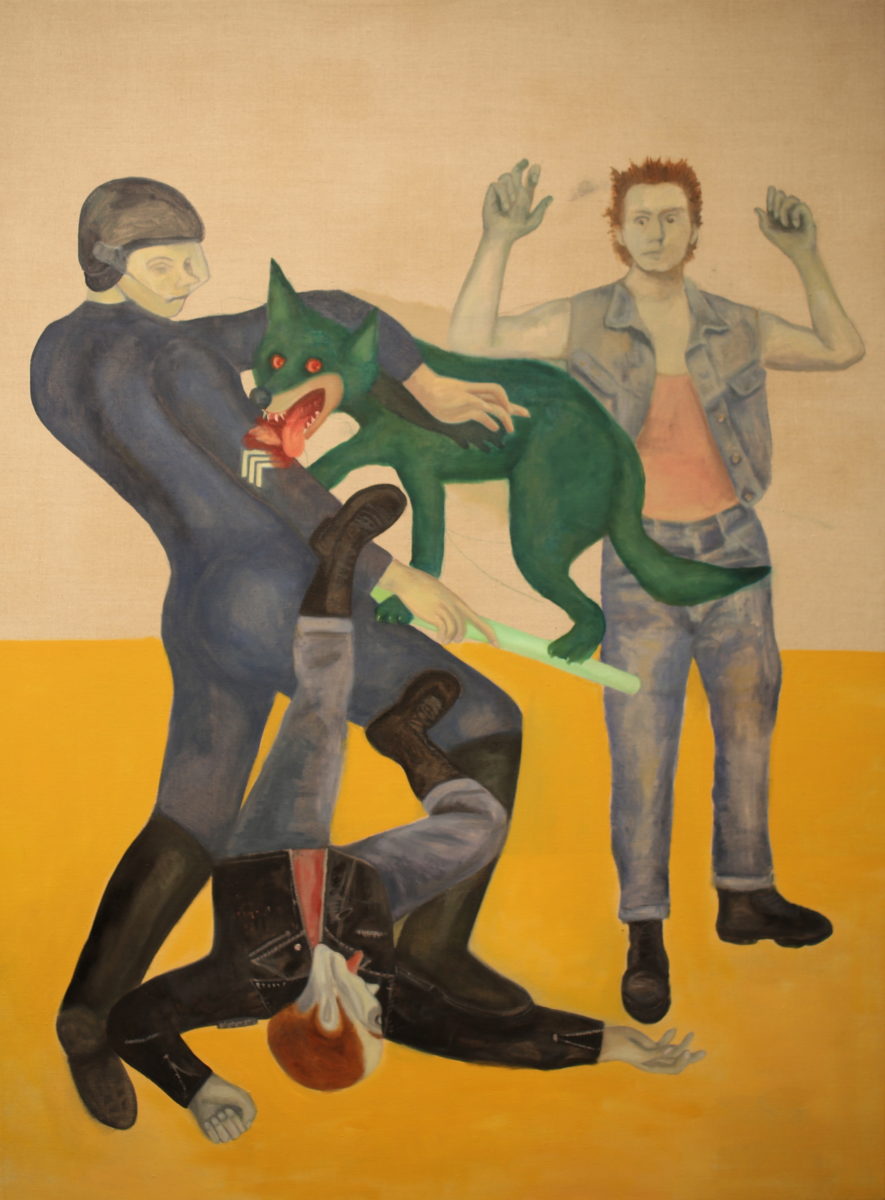

As well as these spatially commanding, loud, physical works, there is an interesting thread running throughout the two spaces of surreally violent paintings, including a room of works at the Giardini by Nicole Eisenman, which carry post-apocalyptic vibes, as human is combined with nature in chilling ways—see in particular, Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (2017), in which a man playing the flute, a frightfully pale sailor with missing teeth and a purple-tinged and nauseous-looking third figure sail down a toxic green river on a boat made from a humungous jaw bone, masted by a tattered white flag. Jill Mulleady is a highlight at the Arsenale, with one wall of paintings depicting red-eyed dogs mauling police figures and arms of bloodied and half-naked figures being bent backwards.

- Nicole Eisenman at the Venice Biennale. Photography by and © Louise Benson

Sculpture is used to chilling effect too—one of the most immersive of these is Alexandra Bircken’s Eskalation, in which forty figures made out of calico dipped in black latex are strewn over ladders and from ceiling beams, their flattened limbs hanging limply beneath them. This is a “dystopian view of what the end of humanity might look like”. Have the figures been burned? Are they old and mummified? This cavernous warehouse looks as though it was made especially for them.

- Alexandra Bircken, Various works, 2016-2019. Mixed media. 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Carol Bove’s twisted, brightly colourful sculptures also play into this idea of an invisible force that comes up again and again—it’s as though we are seeing the result of a traumatic event in lots of these works, but the antagonist is not revealed to us. In Bove’s works, clean and simple modernist forms are bent, dented, doubled over. The steel of the works appears tough, suggesting that the force that apparently twisted them into these new forms is a mighty one.

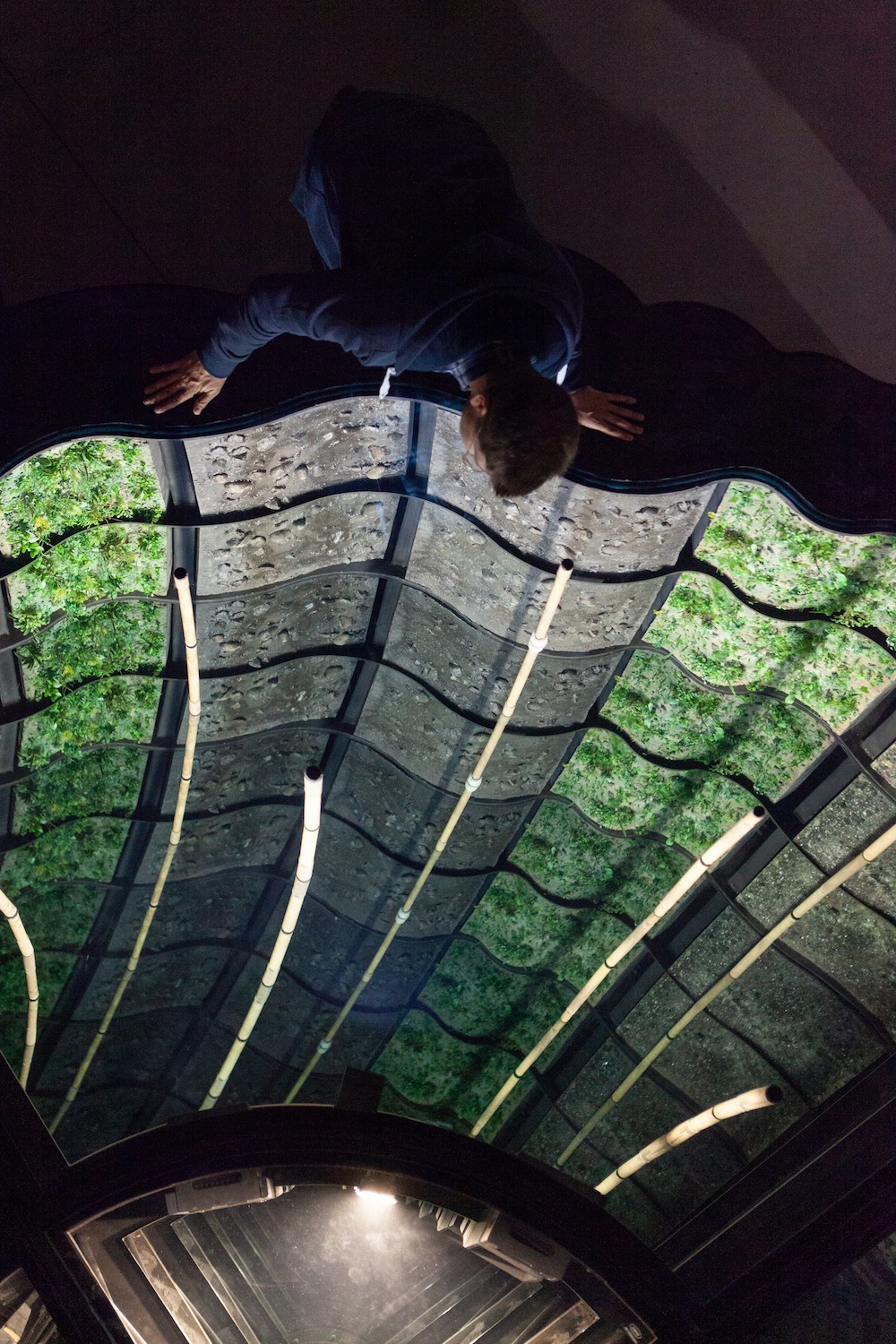

Within the dark labyrinth of rooms in the Arsenale, there are many opportunities to stare into the abyss. At the Philippine pavilion, visitors are invited to remove their shoes and walk on a raised transparent floor, beneath which a network of islands and mirrors creates an infinity effect. Inside, artist Mark Justiniani has placed objects such as plants and spices, which are relevant to the Philippines, and the many different island forms are a nod to the nation’s land mass. “We call it Island Weather because the weather is not just atmospheric weather, it’s about the state of the world,” says curator Tessa Maria Guazon (Artsy). “How fickle situations can be, and how vulnerable we are.”

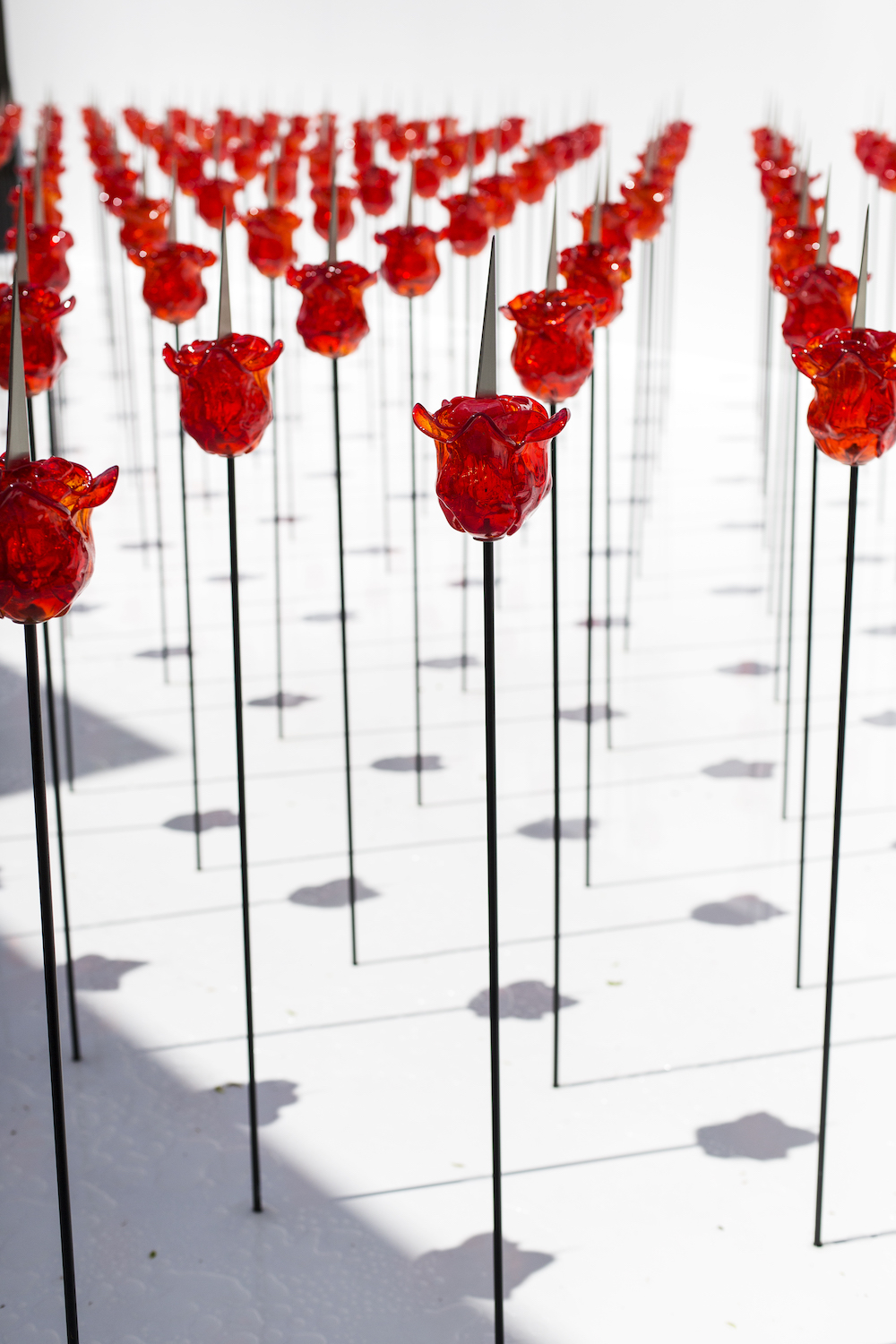

Violence is camouflaged as something far more palatable on first glance at Renate Bertlmann’s central installation at the Austrian pavilion. Rows and rows of meticulously-placed, hand-blown glass roses sit on metal stalks, bathed in sunlight. Look a little closer, and you will see sharp spikes protruding from the top of each one.

Even light is used as an assault on the viewer in places. The most unforgettable of these sits near the entrance of the central exhibition in the Giardini, where viewers are forced to walk through a corridor lit with blinding white light if they are to reach the rest of the show. Ryoji Ikeda’s work is unbearable to look into, and my eyes sting for a good few minutes after entering. Later on, I walk into Charlotte Prodger’s brilliant film work at the Scottish pavilion, heading from the glaring sun outside into the dark for a brief moment, before being bathed in a bright orange hum of light on screen, which stays in fiery form in my vision long after the frame has changed.

All in all, politics is high on the agenda at Venice. But we have moved a step further than even a few years ago. These works don’t feel like warnings of what to come, they feel like an urgent reminder of where we find ourselves right now. As the ever-on-point late musician and poet Leonard Cohen sang in the 1990s: “I’ve seen the future, brother / It is murder.” It seems as though we have arrived in the future.