The gym is an odd place. People of any age

, creed or colour gather here at all hours, in what would appear to be

a highly sociable environment; communication though is reduced to few sentences, many of them including the words “reps”, “sets” or “abs”. Loud pop music resonates in its neon-lit rooms, but everyone is playing their own Spotify playlists through headphones, regularly interrupted by unsolicited commercials. Sweating (as well as grunting, moaning, grimacing) is not something to be ashamed of; it’s actually a matter of pride—proof that we are making an effort. The gym is a fascinating world: an independent microcosm determined by its own rules and shaped by its own language.

“Loud pop music resonates in its neon-lit rooms, but everyone is playing their own Spotify playlists through headphones, regularly interrupted by unsolicited commercials”

In Against Ordinary Language: The Language of the Body (1992), Kathy Acker (who used to be a fitness enthusiast herself) states that bodybuilding—a gym-based activity, consisting in strengthening and enlarging the muscles—is an antagonist to verbal language; the gym, in a sense, encourages our inarticulate self. “Language in the gym is minimal and almost senseless, reduced to numbers and a few nouns,” she points out. Rather than putting together words to let meanings proliferate, at the gym we put together numbers and keep on counting: we count the weights, the reps, the seconds between each lift. We count to ten, fifteen, twenty, and then we start again, until the end of the workout session.

Counting is a way to measure time; by measuring it we can control it. The timespan of a workout is rigorously structured by numbers: as in a Platonic geometric universe, a rational, mathematical order seems to define the gym ecosystem. Think of the activity of lifting weights: the muscular endeavour is regulated by a simple equation (x reps of maximum weight = y muscular growth) in which repetition (of a specific movement on a specific muscle group) is key.

In 1914, the founder of futurism Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote about a “geometric and mechanical splendour” that denoted a brand-new vision of beauty: one of its elements, according to the Italian writer, was “the aggressive optimism that results from a devotion to muscles and sport”, to be mentioned alongside “the happy precision of well-oiled gears and thoughts”. Repetition makes the link between mechanics and bodybuilding quite literal: by repeating the same movement on a machine for a fixed number of times, the bodybuilder increasingly assumes robotic traits. To put it differently: the gym is like an assembly line; what is produced here is a standardized ideal of beauty that the gym-goer—an efficient, semi-robotic worker—creates through the incessant lifting, pushing and pulling.

A minimalist gym, equipped with only exercise mats, is the set of Lucy Beech and Edward Thomasson’s performance 7 Year Itch (2012). The six couples involved in the performance begin executing a series of repetitive movements that initially resemble a cardio workout. Gradually acquiring speed and intensity, the movements reveal their actual meaning: the performance turns out to be a choreographic rendition of sexual intercourse, from the beginning to the final orgasm—as the performers’ moans of pleasure unequivocally suggest. Sex is decomposed into a limited set of gestures, repeatedly and efficiently performed: the metaphor of the gym offers the artists a model for addressing an intriguing topic—the automatization of desire.

After all, when exercise gets too intense, the automated bodies of millions of gym rats might go haywire. An obsessive workout, let’s say, can turn us into stereotyped, lifeless silhouettes. My mind goes to Ei Arakawa’s series of sculptures Smell Image (2012), colourful faceless dummies perpetually frozen in yogic positions; the “smell” mentioned in the title, rather than the consequence of the intense sweating at the gym, refers to the perfume bottles that lie next to them (an allusion to the image of the body in perfume adverts, according to the artist). Arakawa’s fit but inert figures make me inevitably think of Giorgio de Chirico’s silent companions: the mannequins that appear in most of his paintings, standing in the middle of uninhabited squares, depict the disquiet and alienation of the twentieth-century man. But there’s more. In a late work from 1968, titled Rest of the Gladiator, De Chirico would seem to visually foretell the annihilating drifts of contemporary fitness culture. Here a muscular, six-packed man with a mannequin head (forefather of the “lifeless” gym-goer) is standing behind a naked gladiator taking a rest after the fight. In the background is a third marionette character appearing behind a window (or maybe a mirror?), whose body (equipped with a dummy head and a face with no features) is visible from the waist up. This figure calls to mind thousands of Grindr-esque faceless torsos proliferating dating apps and websites, where a glimpse of pumped-up pecs (the product of tenacious gym activity) has become the necessary premise to instigate sexual desire.

“The gym is a stage where a very specific archetype of beauty is produced, performed and consumed daily”

The topic of gym-induced automation is addressed by director Jean-Luc Godard in his sophisticated short film Armide, one of the ten chapters of Aria, an anthology film produced by Don Boyd in 1987. The setting is a gym; the characters are two young women and a group of male bodybuilders. Enraptured by their muscles, the girls (who work at the gym as cleaners) actively try to seduce the bodybuilders: they move gracefully around them, touch their bodies and finally take off their clothes. Despite such distractions, the men keep on working out assiduously; they look detached and emotionless while performing their robotized movements in front of the undressed women. Godard’s camera focuses on the repetitive choreography of the bodybuilders, who look like lifeless (and careless) machines of seduction. The comical effect is emphasized by the contrast between the gym repetitions (quite dull in themselves, choreographically speaking) and the dramatic opera music composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully. “My eyes do not charm him,” says one of the women; “He is made for love,” says the other. At the end of the film, a close up shows the girls cheek to cheek, shouting in succession the words “No” and “Oui”, and moving their heads alternately up and down: an epilogue that takes the mick out of the athletes’ robotic gestures.

However, what is regarded as non-human (the gym rats’ “mechanical” bodies) might be even perceived as something beyond-human: which is the reason why Godard’s bodybuilders can also resemble mythical and untouchable idols, here on earth to be venerated. Their gaze is unperturbed, indifferent to human despair (that of the two girls, whose love offers are blatantly ignored); their vigorous shapes make Olympian deities out of them, holding barbells and fitness gears as divine insignia. The gym, after all, is a sort of “sacred environment”, as stated by Acker: the outside world (the everyday reality) is not allowed inside its perimeter; contemplation and adoration is what is left to those who are not let in.

In some of his works, Australian artist Michael Zavros has represented the gym as a holy temple for aesthetic perfection. The New Round Room (2010-12), for instance, is a view of the Grand Trianon’s interiors in Versailles, meticulously painted in all its details. In front of the window we see a weightlifting bench, transforming the lavishly decorated room into a contemporary gymnasium. The shiny gym equipment lies at the centre, like an altar or a devotional statue—a symbol of twenty-first–century beauty, defined by effort, productivity and KPIs (key performance indicators). Echo (2009), a previous painting by Zavros, depicts an angle of Versailles too, this time the celebrated Hall of Mirrors. Here, chrome weightlifting gears are disseminated in the room and partially reflected by the mirrors on the walls. The view is still magnificent, despite the sombre palette made of grey, black and white: the absence of colour in fact gives the fitness tools a more sacred, sacramental quality.

Either a temple for the cult of perfection or the alienating setting of machine-like choreographies, a place of divine super-humanity or the hangout for robotic non-humans, the gym is a stage where a very specific archetype of beauty is produced, performed and consumed daily. And all of us—the obsessive gym-goers—are the unaware actors in this play. In Alexandra Bachzetsis’s performance The Stages of Staging (2013), the interior of a gym slowly turns into a film set. Mats and exercise gear lie next to screens and shooting equipment; the athletic training morphs into frenetic dancing, interrupted by quieter acts where the performers make personal confessions in front of a camera. For Bachzetsis, the gym is a stage where the drama of life is played out; a place where individual aspirations and desires are consistently fuelled by the relentless workout. This draws up images of Fifteen Million Merits (2011), an episode in the TV series Black Mirror: set in a future not so far away from us, it portrays a society where people can earn their living by riding on stationary bikes in a gym-like automated space. These alienated worker-gymgoers generate power in exchange for “merits”, a form of currency used to buy food, goods and entertainment. Here, exercise means money, and money means realization: the fitter you are, the more successful you can get. An equation that well suits our hyper-efficient, fitness-oriented reality.

But that’s enough talk. I’d better run to the gym.

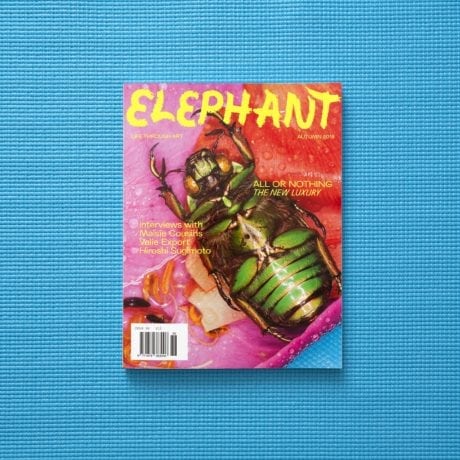

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36