In Rebecca Jagoe’s work, which encompasses writing, performance, sculpture, textiles and embroidery, they directly confrons the mainstream, rigid understanding of gender as the prime arbiter of how one’s body is both treated and received. They cite the violence inherent in conventions of Western medicine, and the harmful impact it can have on an individual’s sense of personhood, including chronic illness, and an insidious sense of shame and disgust with one’s self and body. “Gender has been the overwhelming metric for understanding the functionalities of the body in Western thought,” Jagoe tells me, “whether you are talking about reproductive organs, which should not be inherently gendered anyway, stomachs or legs.”

In a 2019 two-person presentation with Nils Alix Tabeling at London’s Jupiter Woods

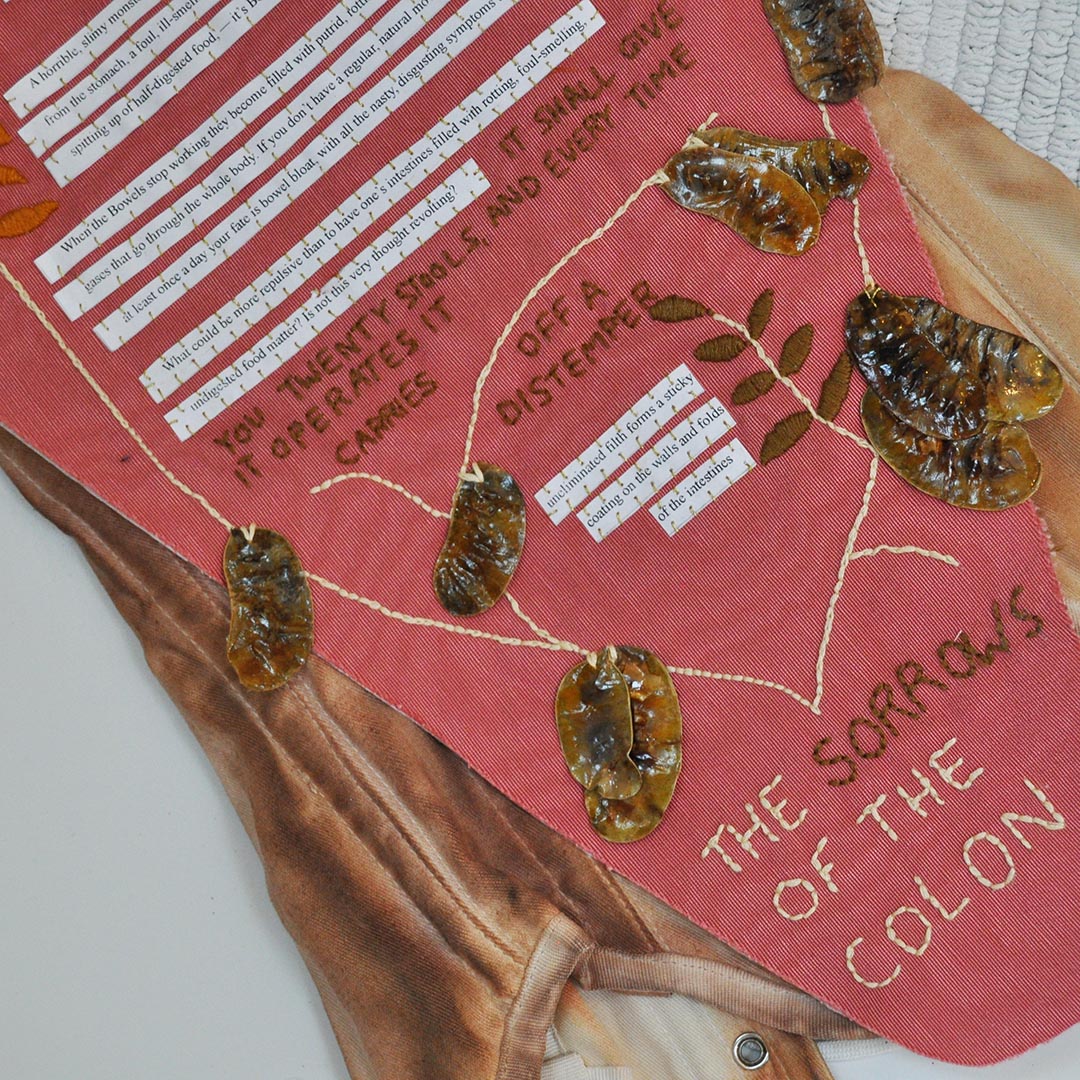

, Jagoe explored the body through sculpture, performance, writing and interactive workshops. Their recent exhibition Florilege placed additional emphasis on illness, shame and gut health. A 35-minute performance titled You Are What You Eat (2019) delves into Jagoe’s existing conflict with food and disordered eating patterns: “Dependent on the time, the amount of food and drink you have ingested, and the number of bowel movements you have passed, your weight may vary by up to 2 kilograms per day,” the performance transcript reads, highlighting the arbitrary or impossible notion of being able to accurately measure one’s own heaviness. “I have always maintained that my own true weight is my weight without food, after a bowel movement, first thing after getting out of bed.”

This isn’t Jagoe’s first mention of feces, and it won’t be the last. “Digestion is something that has been designated morally ambivalent for a long time in Judeo-Christian rhetoric and proselytising,” they say. “A lot of the work was around the desire not to have a body, or to have a body that functioned cleanly and obediently within diagrammatic constructions. The unknowability of my own body, particularly my own guts, is horrific.”

Jagoe also explores the experience of bulimia in her work. It could be said that vomiting provides momentary relief in the stressed brain and body, providing brief respite from hovering anxiety. “Purus, purgare, purgier, purge: the word derives from the Latin ‘to purify’, to rid the body of that which would contaminate it. You yearn to feel pure and clean and empty and hollow; a perfect vessel for moral sanctity,” Jagoe elaborates. “The inability to purge is the absolute worst fear of one who will purge.”

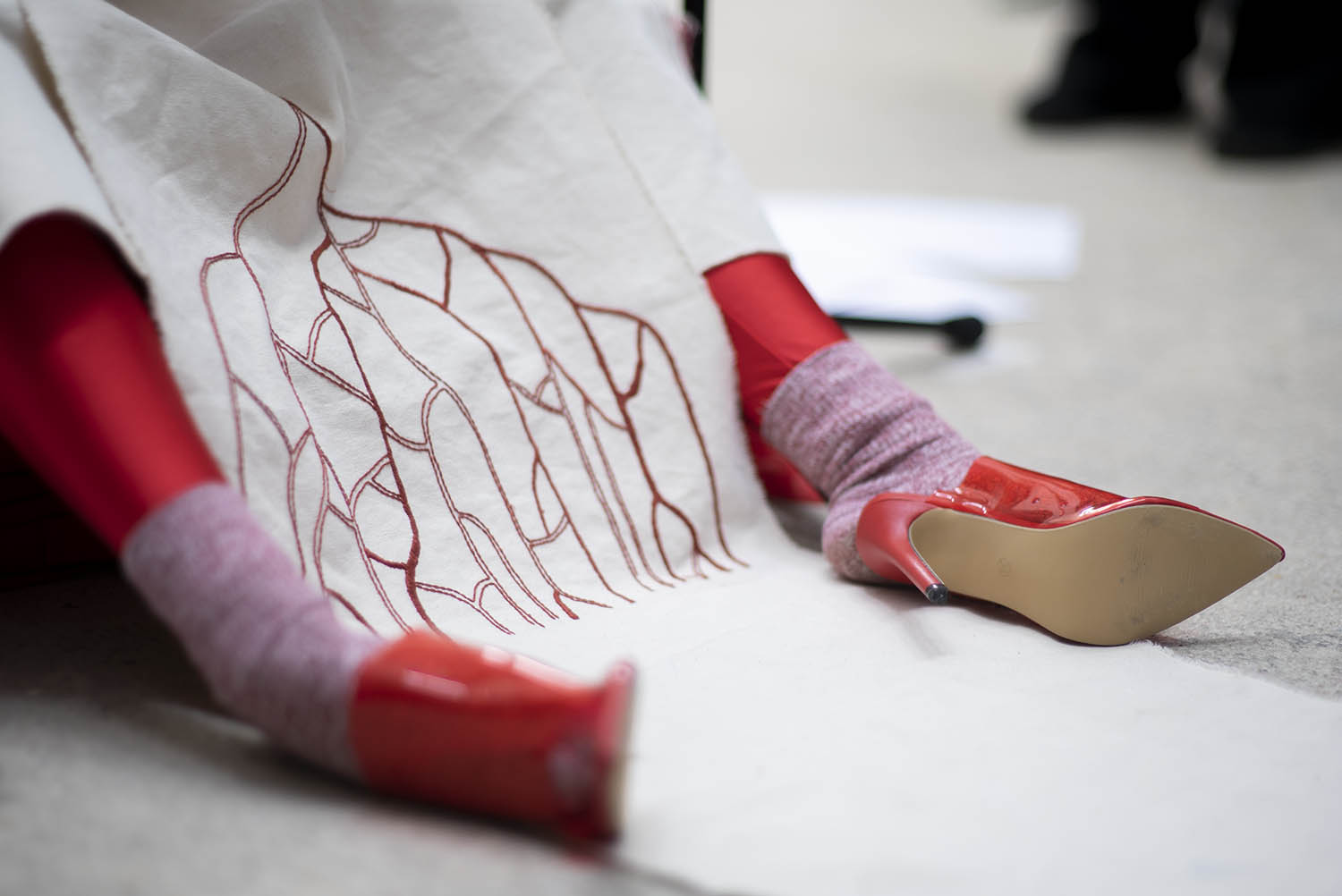

- Ribolitta II, 2017-18. Performance with Jessica Worden, using vinyl and salt dough costume. Performed at Whitechapel Gallery, Odratheque, Musarc Festival, and Every Thing at Assembly Point. Shown here at Odratheque. Images courtesy Yiannis Katsaris

Jagoe has continued their exploration of gut health, with the recent release of their podcast, Shiten Mouth Ful of Tordes, conceived in collaboration with Wysing Arts Centre. The title, according to the artist, is a middle English proverb roughly translating as “to fill one’s mouth with shit”. The programme brings together Jagoe’s ongoing work in writing, as well as her research and musings that examine gut health and herbal cures associated with laxatives, the latter of which influences Jagoe’s work due to their personal 14 year stalemate with an eating disorder and abuse of self-administered drug evacuants.

“Digestion is something that has been designated morally ambivalent for a long time in Judeo-Christian rhetoric”

Using their own personal narrative throughout, Jagoe cites the work of Hildegard von Bingen, a German nun living in the twelfth-century, who wrote prolifically about the relationship of the individual self to culture at large, as well as the association between astrology and gut health. The arguments posited by Hildegard (as Jagoe playfully refers to her) prove that “bodies are ruled by the micro and macro”, they say. “What is wonderful about a lot of medieval lore is this direct relationship between the interior body and exterior geography that is incredibly intimate.”

Intimacy as an antidote emerges in Jagoe’s writing and editing practice, perhaps most explicitly with On Care, a new anthology co-edited by Jagoe with Sharon Kivland, published in August. On Care compiles a chorus of voices, including those of artists Sophie Jung

and Victoria Sin, and writer Jamie Sutcliffe, to discuss the politics of care under neoliberalism, examining those deemed “worthy” of care, and those who are not. Significantly, in noting that care is “a matter of responsibility… an imperative”, the book ultimately defines it as “a way of approaching the world beyond selfhood”.

In our conversation, Jagoe cites Lynda Benglis as having a strong influence, and the idea makes sense. “But I certainly wasn’t brought up to question the hegemony of Western scientific thinking, and so often my body, my health, both mental and physical—though arguably that distinction is arbitrary and Cartesian—has been explained to me, as phenomena that other people more fully understand. You do not know you are ill, is the implication, you do not know if something is wrong, only we can decide that.”