The art world has a particular fascination with age, enamoured by the precociousness of youth and worshipping the wisdom of the elderly. Artists often speak of a U-shaped career path, enjoying recognition early and late years, but working in relative obscurity throughout the middle of their lives. Art is fundamentally based on experience, which is something we traditionally consider a benefit of getting older—but the world around us also changes.

We speak to an artist born in every decade of the last one hundred years, to find out how age really affects the art they make, and how they feel about their place in the world.

0s

Lily L was born in London, 2010

I like being creative; my imagination takes me to another world, just like reading does. Things don’t have to be perfect; like Picasso’s style, it’s all over the place. My earliest memory of art is sitting on my grandma’s lap making all sorts of things; like a bottle snowman, a cuddly rabbit and a plaster cast of seeds and leaves from the garden.

I don’t feel like my age stops me from doing anything that I would like to do. I can always be creative when I want to be. I am on the art council at school and we do portraits and landscapes, and I’m making a giant 3D pencil at the moment. I definitely see myself as an artist when I am older. When I am famous, my friend Viola and I have to buy Mr Griffin (our art teacher) a mansion by the beach in Italy.

I was elated to hear the news that my work was going to be shown in the Royal Academy’s Young Artist’s Summer Show in London last year, and I was really happy because I had two of my paintings chosen. I did feel sorry for my brother, Jack, because his paintings weren’t chosen. One of the paintings is of my grandma and grandpa. I painted them smiling and wrapping one arm around the other’s shoulder. I copied it from a photo of them, using acrylic paint. I wanted it to be realistic but not exactly perfect, but I think it really looks like them.

The other was a painting of me hugging my grandma. We are looking at each other. I painted her wearing her favourite jumper, which is very snuggly. This painting is very special now because my grandma has just died. I’m very happy that she was alive to see it hanging at the Royal Academy. She was very proud.

Lily L spoke to Emily Steer

10s

Sasha Alcocer was born in New York, 2002

I’ve been taking pictures since I was twelve, on an Olympus point and shoot which I still use. I started shooting around Chinatown in Manhattan, where my dad lived at the time. It was my first experience of freedom; it was just me taking pictures on the streets.

I feel I can form a connection through photography, and New York is so inspiring—you can never get bored. There are so many people from all over the world here. My dad is Mexican and my mom is Russian; who would have thought that those two people would have met?

I think being a teenager has let me be more open to new things. I’m just like: “Yeah, sure, why not?” It’s helped me define myself as an artist. Going to art shows, it’s really easy to talk to people, they’re like: “You’re so young and cute!” People think teenagers are clueless, but I know a lot more than people think I do.

It’s been weird growing up with social media, and a lot of people get caught up with the number of likes you get. It’s so fake. You try to tell yourself it doesn’t matter, but then you end up wondering if people actually like your work.

I started this project last year called Crush, where I curate art shows in my uncle’s small restaurant on the Lower East Side. It’s about bringing back that real-life connection, not just liking stuff on Instagram. It’s been almost a year now, and there have been five shows so far.

I don’t want to limit Crush to a certain crew in New York. It’s open submission, and I never ignore anyone. It’s not just young, cool people; I invite my friends, teachers, family and neighbours. It’s about being really fun and open. I think community is really important. It’s been hard to time manage; I’d like to do more but I have school too. I’m very hopeful about a lot of things; I think it’s a great time to be a creative teenager.

Sasha Alcocer spoke to Louise Benson

20s

Phumzile Khanyile was born in Soweto, 1991

As an artist in my twenties, I still feel like I’m just beginning and learning everything at once. I can still play around since I haven’t solidified any concept of who I am—I can constantly grow. The only disadvantages are that people still tend to talk over me and I’m not taken seriously; but my strategy is to listen, ask questions and acknowledge the other person.

I had my daughter when I was twenty-six, in 2017, the same year I had my first solo show. I was so consumed with the exhibition that I only found out I was pregnant at four or five months; so Azania came at a very busy time when I had to find a way to juggle being a new mom and an upcoming artist. But she always comes first: I really want to be present for her, and for her to know what I do.

I constantly have to dismantle my understanding of my practice as it’s become less spontaneous since having a child. Postnatal depression, too, makes you lose your zest for life: I’ve had to go through the process of trying to believe in myself again. I remember being explicitly told not to have a child because that would ruin my career in the arts; but because of my age I’m still able to bounce back. I follow my heart and not other people’s opinions.

My practice took a different shape after giving birth to my daughter and my self-portrait series Plastic Crowns… I had a really hard time convincing people that it had a lot of intellectual layers and wasn’t just a fun project with no depth. I’ve always believed that my life should inform my work and not the other way around.

The greatest gift would be to have kids studying my work twenty or forty years from now. I want them to learn to tell their stories the way they want to—to know that there was a girl from deep in the township who got out purely through art. I want them to experience the work, to feel it rather than intellectualize it. I have no regrets, but I wish I’d known when I was younger that I mattered, and that everything I create has value.

Phumzile Khanyile spoke to Emily Gosling

30s

Alex Da Corte was born in New Jersey, 1980

I always think about what brings one comfort in old age, or equally, when you are feeling ill or need to be cheered up in some way. The kneejerk will always be to watch a bad film like Batman Returns, it’s so familiar that it’s like you’re not watching it at all. These cultural touchstones of a certain era become like family, and they are also the things that are worthy of debunking or demystifying.

When I include a character such as Marshall Mathers or Elvira in my work, I want to think about them beyond their masks and ask how they have contributed to society. Not only that, but how have they contributed to the collective psyche of people that have grown into their middle age—if forty is middle aged.

I don’t feel like I’m middle aged, because my work is so youthful. Artists are always asking questions and looking at things in the same way that you would look at them if you were a young person—we are totally inquisitive about the world. It evades this idea that at “x” age you must do “x”.

To escape cynicism has been the most pressing challenge; to evade seeing the world through a jaded eye and remain happy to absorb and hear new things that aren’t familiar to me. I am part of the generation that bridges the gap between the analogue and the digital, and I like to think about what was lost and gained in that transition. I don’t have any interest in nostalgia, in the sense of looking back as a way to fetishize something that had no value at the time it existed.

Recently I have been thinking about PVC tubes, which I used a lot early on. I was always using recycled plastic or stuff from the store, and it was about being resourceful. Now there are so many geopolitical conversations around plastic, which changes the way I work with these things, because it embeds a different spirit in them. You should never lean on a particular material or fail to change up the way you are working. I have to constantly leave question marks at the end of my statements, to ask what is next. Because we know that change is good.

Alex Da Corte spoke to Holly Black

40s

Monster Chetwynd was born in London, 1973

In my forties I suddenly feel disturbingly capable and powerful. You have this intense clarity; all the years you’ve spent analysing and questioning build up to an incredible backlog of experience. That gives you a pretty strong sense of what you can get away with, and what you can’t.

When I was younger, I couldn’t see the trajectory other people could. But I’m very into going along with the ride and feel things very instinctively. The thing I used to fear most was being trapped in a way that meant I couldn’t be a creative person, but there are so many ways to be expressive or playful—you can do that even in a conversation.

You definitely travel through different zones as an artist: it’s like you’re having your mettle tested at the beginning, when people don’t understand what you’re about. But you’re tenaciously producing until you have a body of work that you understand in a confident way, and the discourse around it changes. It’s fascinatingly gradual and continuous, like each piece is a stepping stone.

By the time I had a child I had already had a lot of time to develop my work and be confident in it. In my opinion, it’s very important that artists have children: if people who are risk-takers, intense, driven and mindful of culture can do that, they’re nurturing a percentage of the next generation. And that percentage will be adaptable, innovative and potentially subversive thinkers contributing to the demands and dilemmas of the future.

I can’t think of any negatives to being in my forties. In Hokusai’s era in Japan, artists often took on different names at different ages. Decades in your development and rites of passage can signify a different person: Monster, which became my name in 2018, is really useful as it is non-gender-specific, and I am becoming very engulfing—the two people I was named after before, Spartacus and Marvin Gaye, had hideous ends to their lives.

Ambition has never been my main focus; the formula I’ve worked to is a recipe of action and loving what you’re doing. Just having the most insanely mischievous time, by default you’re interesting and of worth to people.

Monster Chetwynd spoke to Emily Gosling

50s

Mariko Mori was born in Tokyo, 1967

I’ve always tried to find the best way to express my ideas, but sometimes the technology was not yet available. I often collaborate with engineers and have developed new software and hardware to produce the work. The technology is just another vocabulary for me.

I feel like I was born at the right time. Sometimes I was too early, and the technology was not ready, but I could contribute to developing it. It gave me more time to really think through and decide the most appropriate media to produce my work.

I stopped shooting my own image in 1998, but I still do performances. What’s rewarding when you mature is that, obviously, you have more experience, and I think your confidence is much stronger. When I look back, I can see that I always did the best I could at the time, when I was not afraid.

There is a benefit to not knowing what you’re doing—you just do it! This is wonderful, but when you have more experience you don’t need to make as many mistakes. You are more focused, and you save yourself a lot of time and energy.

Negative things happen, and some disappointments, but it’s really your own judgment that is negative. In fact, the negative thing can give you the best direction to take. You don’t need to fight, you just need to pass through. Afterwards, you will find out that what you thought was negative is actually positive.

I think that the younger generation are on a good path. They’re very eco-minded, more willing to pursue equality and have a greater sense of being connected. I feel very positive about what I’m trying to do because I feel I can now get that support from the younger generation, and I feel positive about the future.

Mariko Mori spoke to Louise Benson

60s

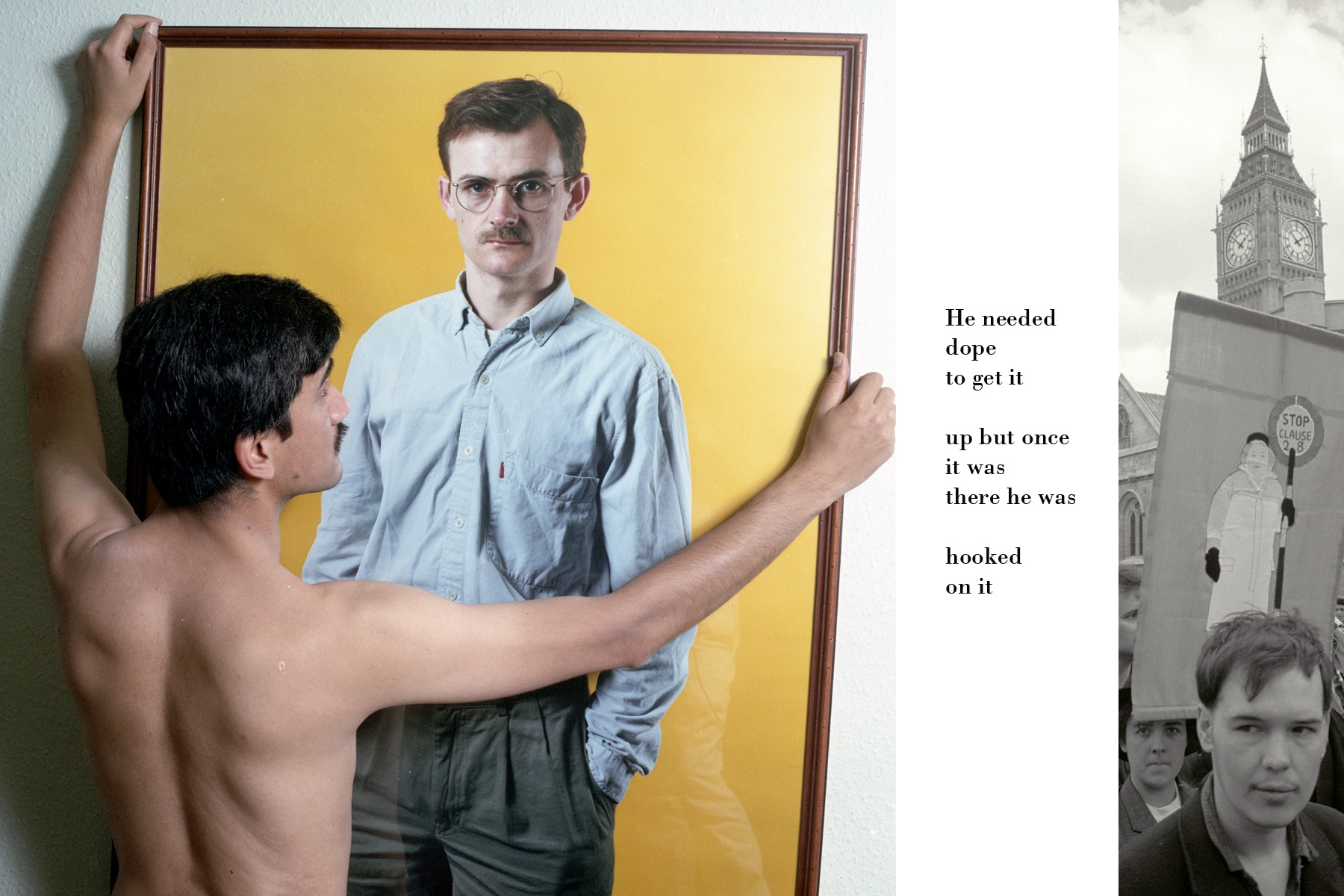

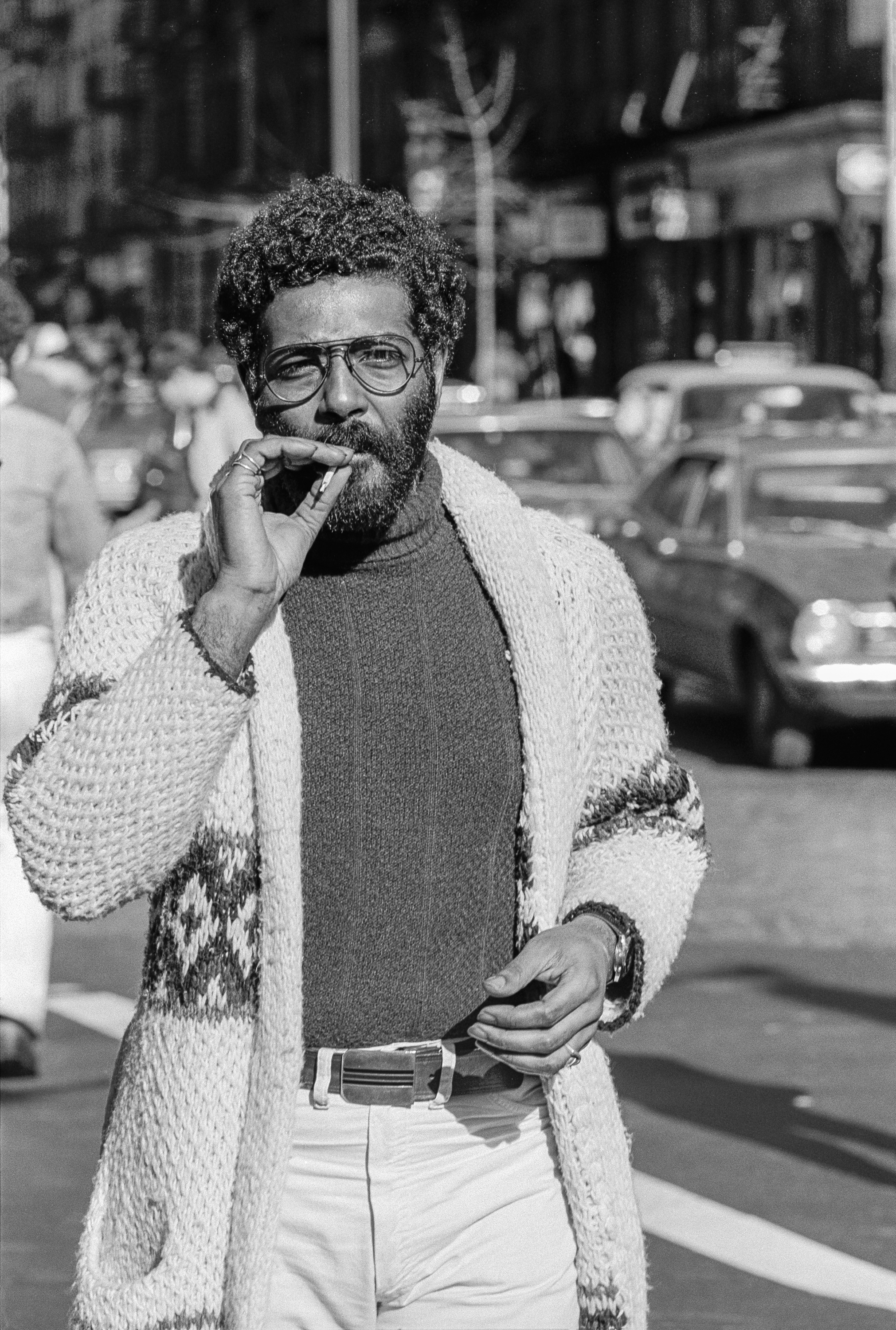

Sunil Gupta was born in Delhi, 1953

Age has taught me that my basic line of enquiry has not changed—which is, of course, what does it mean to be a gay man of Indian origin? What I have learnt about art in general is to try and shed as many of the prejudices that you learn at an early age as possible.

In the first part of my career, photography and art were separated; photography became work, in the sense that I worked for Fleet Street for a living, and art was something I did for myself, but it had no outlet at the time. It seemed to me that my subject matter of race and gay men back in the eighties was not of that much interest to the commercial art market. But in 1995 I was diagnosed with HIV, so I decided that I’d rather make art than administer exhibitions.

My art has been affected by my age. When I was younger, I was very keen to go out and make as many pictures as possible. Now I feel I need to work with the visual archive that I’ve inadvertently created over the last forty years. If I could, I would tell my younger self that I need to be a lot less anxious about seeking out ideas and executing projects and instead focus more on living a life. In the end, that’s where my projects came from.

It seems to me that here in the West we don’t think that age necessarily brings wisdom, and sometimes you feel like you are struggling to get heard. We are fixated on youth and the “new”. In Asia, I feel people of all ages are much more receptive to what I have to say as an older person.

I’ve been involved in education, on the periphery, for quite a long time now. I find the classroom a very stimulating place. It’s been the place for much more formal and particular kinds of conversations about art and photography. Nowadays, I find it interesting talking to younger generations about what we can make of our contemporary world.

I’m very excited about the coming decade as I’m going through my archive. Meanwhile, I’ve also gone back to making new work partially on the street (I can’t seem to give that up)—with the same subject matter of gender and homosexuality.

Sunil Gupta spoke to Charlotte Jansen

70s

Lynda Benglis was born in Louisiana, 1941

When I made works like Minos and Siren in the 1970s, I was thinking about my time scuba diving in California and how one might see something or feel when underwater—that buoyancy—and the idea that a woman always feels the buoyancy of her body and cycles. I think intuitively I was referring to the feeling that we float, like a mermaid or a pregnant being. Artists all through time allow themselves the freedom of doing that.

I am the oldest of five children, and I always knew I wanted to invent things. I invented stories for my sister about all of our dolls coming alive on New Year’s Day. I think that in the same way, my works have to have energy. I like the idea of the material taking on the symbol of life.

I’m having an interesting experience lately, and I had it when I was a child. I look and I have an illusion—my mind does tricks as if I’m stoned. I first experienced it with my mother when I was around six years old; I could somehow control the space of her face, and this is what is happening to me now. I like to try and see how I can make materials appear to shift.

Art is my best way of passing my time; to do something that’s pleasurable but also pleases other people. It gives me a lot of pleasure to be desired in that way. But it was a risk I had to take. I had my chances to be connected with different men in my life, and it’s not that I didn’t love them, but finally it didn’t work out. I had disappointments, but when I look at it now I see how valuable these experiences were and I feel very lucky to have had what I’ve had.

Real art doesn’t age, because it’s about connecting with an idea. Art is logical. You see it, and you understand the time; it marks the time, it explains what the time is, how people are feeling. It’s not an accident that people do art. It has to do with why. Why are we alive?

Lynda Benglis spoke to Charlotte Jansen

80s

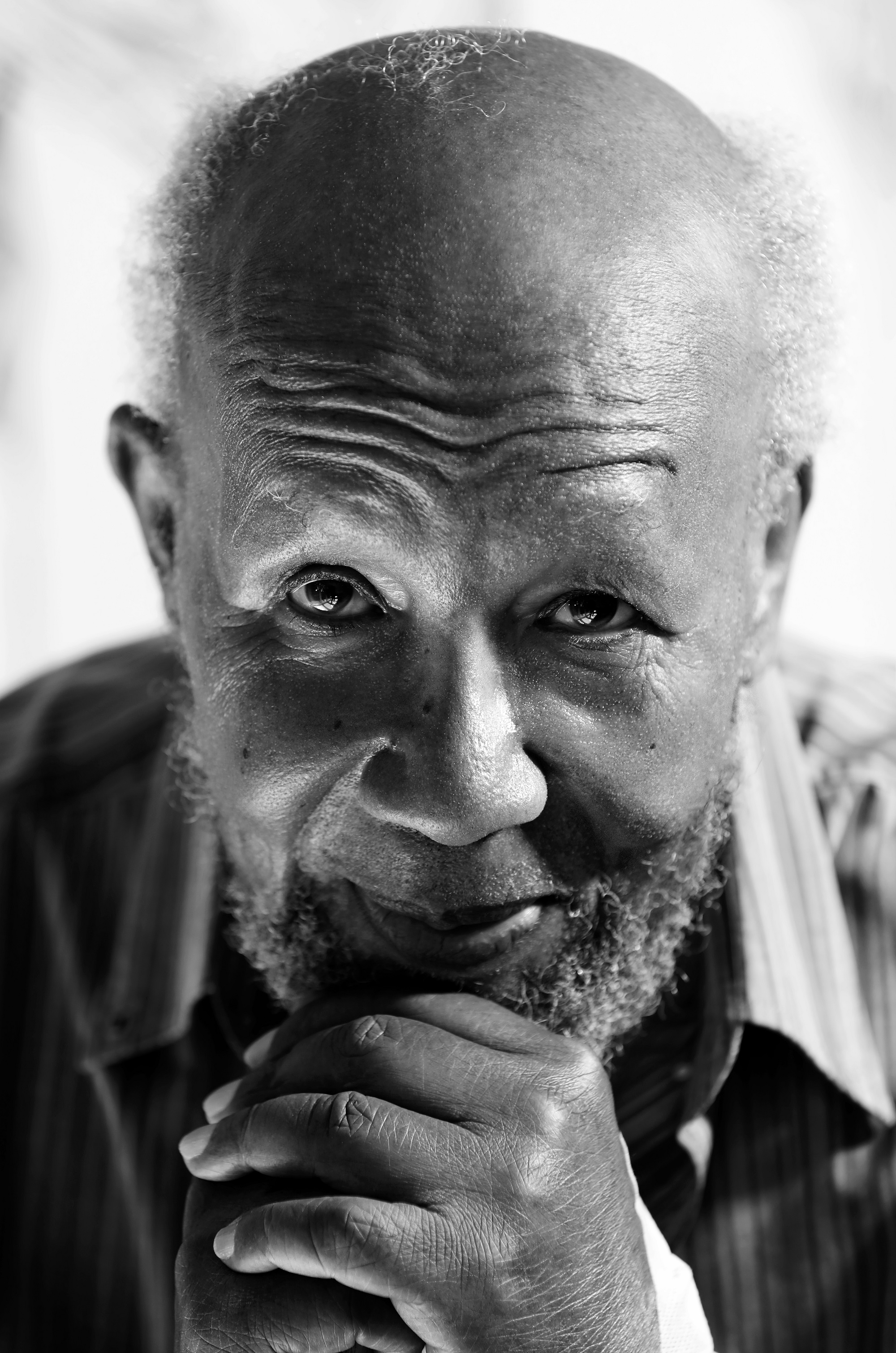

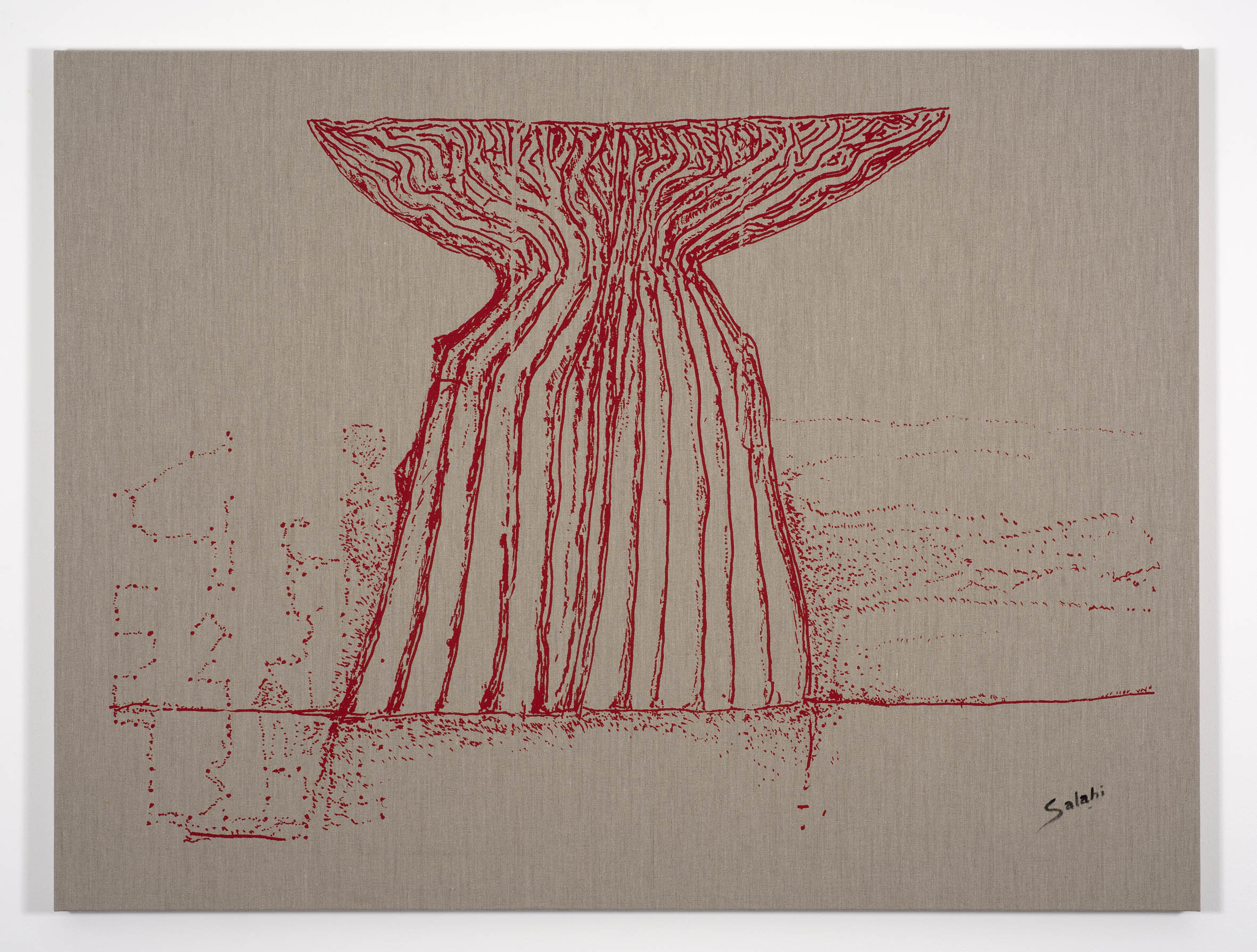

Ibrahim El-Salahi was born in Omdurman, 1930

I have heard that I’ve been referred to as the “father of African Modernism”, and I appreciate the sentiment of those who have said such things, but it would be a little arrogant to agree! I have been in the right place at the right time, and also the wrong place at the wrong time, in my life.

I was the first African artist to have a retrospective at Tate Modern. The recognition for contemporary African art felt like a very long time coming. I am optimistic about the way the art world is changing since I started out.

I have always looked at how to engage my audience. This has changed as my experience and circumstance has shaped me but remains a constant. I have employed strategies to deal with whatever circumstances I was in.

When I was put in prison, I used scraps of concrete casing, which I would draw on, and hide from the guards. When they were not looking, I would put them together to make the whole picture. Thereafter I was concerned with the notion of the nucleus and the whole, and the way I worked employed this additive approach. The visions from my earlier career had disappeared and it became more of a meditative and religious process for me.

In my last period in Qatar I worked in the Amiri Palace. My office changed through time from a grand building to a desk in the archives section, where I found small pieces of paper which I used to make a drawing every day for months. This installation of dozens of drawings is now in the collection of Sharjah Art Foundation and is one of my most important works.

More recently with my sciatica and back pain, the Pain Relief series was created using the back of my medicine packets as a malleable material on which to form images that I wanted to make in large format, transferring them by screen print to canvas. This was a direct consequence of health issues I have had to adapt to.

I am very thankful for any praise and recognition I have been given and that has been dedicated to my work, and as such it is nice to feel so valued.

Ibrahim El-Salahi spoke to Holly Black

90s

Luchita Hurtado was born in Maiquetía, 1920

Art has always been part of my life, and I have always thought of it as a kind of diary of what I’m living through. Life influences the art you make: if you’re happy, if you’re sexy, if you’re sleepy, all these things. I have always accepted myself: I accept how I feel, I accept how I live.

Having two children and working to make a living was very challenging. I married and had my children very young, and he left us for someone else. Some of the highlights of my life that I look back to are when my third husband was alive, when my children were young, and they were all with me. It was perfect, that was the way I wanted it: I wanted the cooking, I wanted the art making, I wanted it all.

I worked in the dark for so long and now in my later years there has been some recognition. I started when I was twenty. Success has never been important to me; it was such a surprise when it really happened.

I used to use my body in my work, but I use words now. It’s a temper of the times. When I used my body, it was the idea of “that’s all you have”. You’re born and you live and then you die. We make all kinds of stories, but we really don’t know whether there is a heaven or a hell. We are an energy, and it is either good or bad.

In the wider world I think there is a kind of disease going around. People are nasty to each other instead of loving each other—especially the people in charge of things. We are in very unhappy times, but it can’t be the end of the world—we should not have this kind of future for our children. I can’t be carrying signs and joining protests anymore so I just paint and live the best I can. I’m an old woman and I’m enjoying my last days. I’m supposed to be one of the most important people in the art world: that much I know. My son dressed up and went to accept an award for me in New York recently. It weighs thirty pounds, I hear!

Nowadays, I live alone, I do my own cooking and I watch television a great deal—I am very fond of television. It’s nice being this old and painless. I am so grateful that I am painless. As a matter of fact, I recently bought a shirt that says “grateful” on it, and I’m wearing it now! Because that is how I feel.

Luchita Hurtado spoke to Emily Steer

This article is featured in Elephant Issue 42

BUY NOW