Considered and reconsidered by artists and writers alike, the lobster has been a surrealist mascot, a fashion accessory, and is now entering a new phase as an emblem of right wing ideology. An enduring but mutable symbol, it has stood for extravagance, maritime nostalgia and sexual innuendo. There is, however, an unavoidable violence to the lobster: “He is the old hunting dog of the sea”, writes Anne Sexton in her poem Lobster. Hefty claws and an armoured body hint at the creature’s aggressive tendencies, but, of course, violence is folded into how we cook them, too. Sexton observes that we “take his perfect green body / and paint it red”, a reminder that the scarlet shell we so often see in the visual arts is the result of violent human intervention: it’s only after boiling that a lobster changes colour.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Still Life with Lobster and Nautillus Cup, 1634

In the wild, lobsters are confrontational loners who abide by strict hierarchical rules based on violent displays of strength. This is why right-wing psychology professor and public intellectual Jordan Peterson has adopted the crustacean as an emblem for his paternalistic philosophy: his brand of intellectual machismo argues that returning to a more traditional, heteronormative society is the answer to our contemporary ills. In short, Peterson’s teachings suggest that, because we share some ancient DNA with the crustaceans, the same kind of rigid social organisation is best for us humans, too. To support his cause, Peterson has recently launched a line of lobster-printed merchandise: the navy blue t-shirts feature small red lobsters with large claws arranged in a uniform pattern, like a regiment of angry insects.

“The scarlet shell we so often see in the visual arts is the result of violent human intervention: it’s only after boiling that a lobster changes colour”

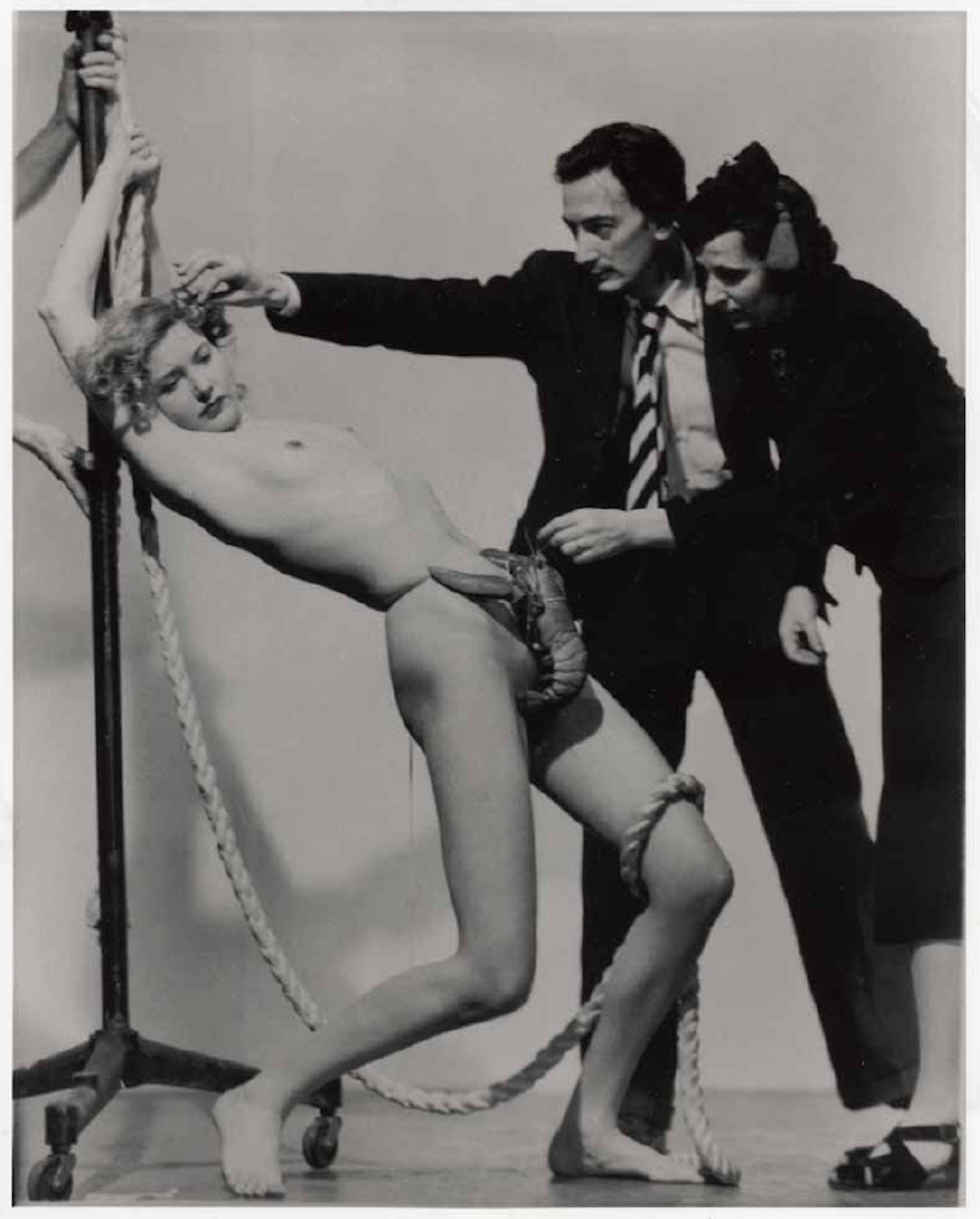

Aggressive looking and undeniably phallic, the lobster makes sense as shorthand for patriarchal dominance, but its symbolic history in the arts is more nuanced and complex. The most iconic art lobster is Salvador Dalí’s mixed media piece Lobster Telephone (1936), which established the crustacean as a mouthpiece for playful sexual expression. The surrealist movement was certainly not free from sexism and gender bias, but the movement’s aim was to be an avant-garde that challenged societal norms by embracing the chaos of the unconscious. The subtitle of Peterson’s book 12 Rules for Life is, however, “an antidote to chaos”. The lobsters in Dalí’s work are sensual creatures, exploited for maximum potential for innuendo; Peterson’s iterations are rigid and flat—much like his perspective.

Dalí was captivated by the lobster’s capacity to stand for both phallic symbol and castration instrument, and frequently evoked this duality in his work. In 1937, he collaborated with designer Elsa Schiaparelli on a dress for Wallis Simpson, painting a lobster onto its silk tulle skirt. If worn, the creature’s fanned tale sits provocatively over the vulva, while its body extends down to the hem like a huge, red phallus. It’s a piece that revels in the contrast between elegance and base sexuality, soft femininity and its tough masculine counterpart. Here, the lobster is an embodiment of Freudian sexual neuroses, at once a yonic and a phallic symbol.

Ever-perverse, the lobster is no stranger to a re-brand. As David Foster Wallace explains in his essay Consider the Lobster, the name comes from loppestre, which mixes a distortion of the Latin for locust with the Old English loppe, meaning spider, giving us, as he puts it, ‘giant sea insects’. The American variety was once so abundant it was known as “poor man’s protein”, until overfishing meant supplies dwindled and its stock went up. Though its European counterpart has always been more rare and expensive, and in the seventeenth century lobsters began appearing in still-life paintings as a symbol of wealth and indulgence. In Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s Still-Life with Lobster and Nautilus Cup (1634) a table is piled high with valuable treasures including silverware, fruit and a bright red lobster, one claw drunkenly lolling off the table. It simultaneously shows the allure of a life of excess and warns against it: this lobster is a dead one.

“Aggressive looking and undeniably phallic, the lobster makes sense as shorthand for patriarchal dominance, but its symbolic history in the arts is more nuanced”

Jeff Koons teases these classical associations with status in his piece Lobster (2013). Almost five foot tall, this sculpture of an inflatable pool toy is nostalgic and playful, again calling on sexual innuendo. Koons uses aluminium and polychrome to match the tactile qualities of inflated plastic, right down to its puckered edges, enjoying the contradiction between medium and subject matter. Here, the lobster’s violence is neutered: hung upside down by a steel chain, it is on the one hand a blow-up phallic toy, while on the other, the yonic fan of its tail alludes to sexual duality, recalling the same intention of Dalí and Schiaparelli’s sartorial innuendo.

That a marine scavenger like the lobster has endured as a fashion symbol is testament to its widespread appeal, though contemporary iterations tend towards camp, cartoonish representations: New York designer Kate Spade’s novelty handbag is more Disney than Dalí. Likewise, while jeweller Tatty Devine’s articulated plastic necklaces snap their claws against the collarbone when their tail is pulled, the mood is playful rather than menacing. These are joyful objects, designed to bring a smile to someone’s face.

Just as important to Dalí as to Koons, play is a recurring theme in how lobsters appear in the visual arts. Performance artist Rebecca Goyette’s “lobsta porn” films expand on this, marrying an exuberant, camp aesthetic with a return to the realities of lobster biology. They take as inspiration the biological quirks of lobster sex, in which the males have two penises, and the females shed their hard shells and squirt urine into their chosen mate’s den as foreplay.

Pornographic parodies that trace the boundary between consumption and sex, pleasure and violence, humour and titillation, the films celebrate the lobster’s perversities—actors wear speedos with multiple silken penises attached, or extravagant pink vulvas. Their hands are covered with padded latex claws (like boxing gloves), and their skirts extend into tails that float behind them as they swim. Mostly the outfits are varying shades of red, orange or pink, but in Masshole Love Goyette appears as a powerful blue lobster queen. The editing mimics the genital close ups and bodily sound effects of porn, and the artist and her cast simulate sex on boats and in the sea. The films explore shame and pleasure, updating the lobster from a lonely phallic object to a symbol that’s queer, social, and centres feminine sexual agency.

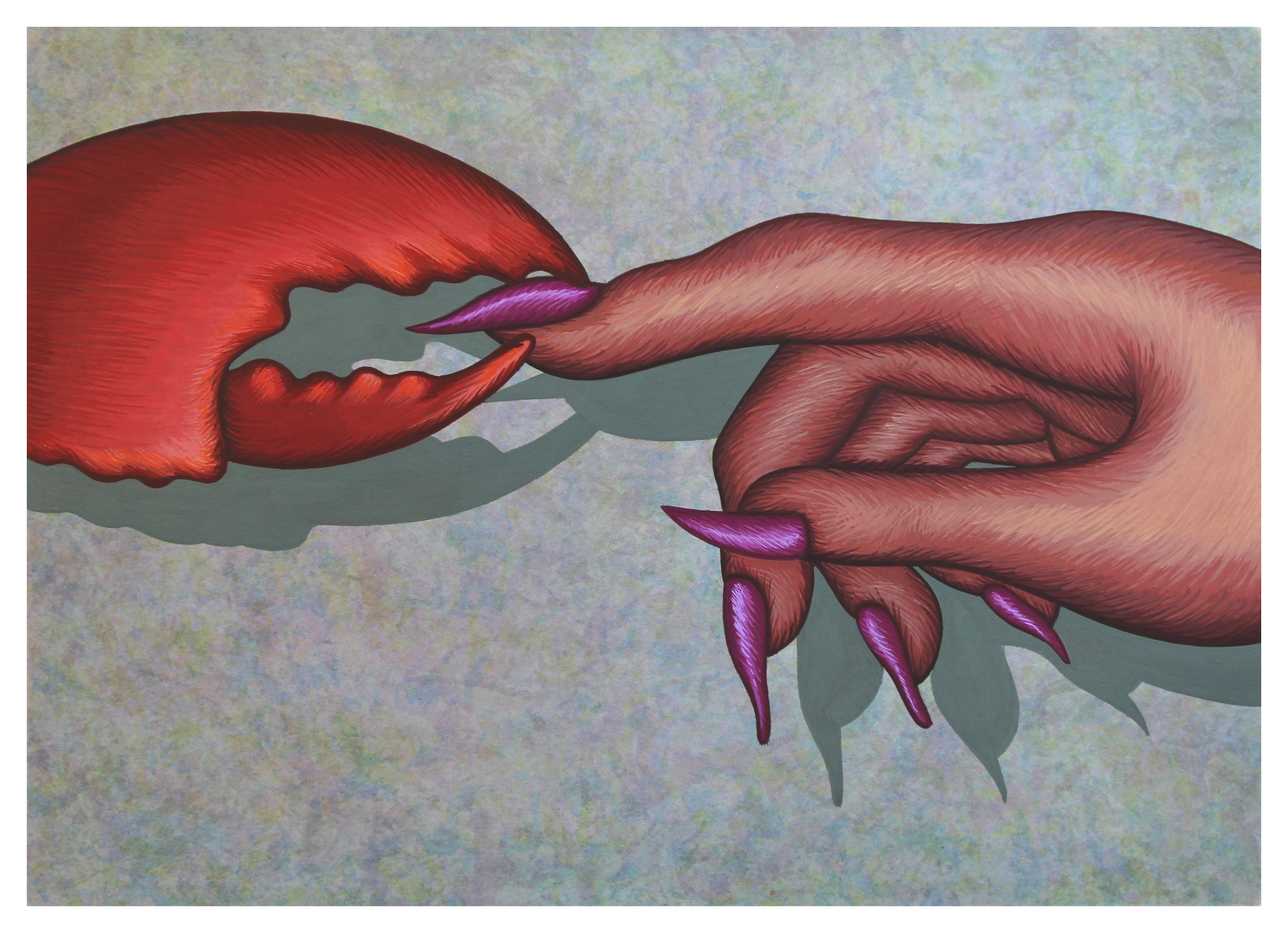

Julie Curtiss is another artist who places the lobster within a feminine symbolic. Curtiss (who counts Rene Magritte and Louise Bourgeois as influences) paints a surreal, textured world where thick ropes of hair and painted nails are recurring motifs. In Link (2018) is a close-up of a lobster’s claw and woman’s hand meeting pincer to purple talon. It echoes Michelangelo’s Adam and God touching fingertips across the void between mortal and immortal worlds, except here, claw grips nail in an ambiguous gesture: is this cross-species handshake threatening or friendly? Charged with eroticism, it conjures the master/slave dialectic, toying with the power balance between humans and animals, predator and prey.

“Associated as much with castration as with masculine potency, the lobster’s symbolic flexibility has kept it relevant through the ages”

By contrast, the hyper-real anatomical detail of Tristan Pigott’s Lemon Peeler (2016) is a reminder that the lobster is not just a symbol but a living organism. Though the painting’s palette is artificial, even kitsch—the lobster’s shell is a custard yellow—it raises questions about when and how living things become inanimate objects: because of its unnatural colour, it’s impossible to know whether this lobster is alive or dead. The naturalistic detail makes it easy to anthropomorphise the look in its beady eye as one of disapprobation. After all, yellow is a colour associated with cowardice, and perhaps the colour of its shell stands as a rebuke to the barbaric cooking practices Foster Wallace was at such pains to point out in his essay—we may be one of an adult lobster’s only predators, but it’s hardly a fair fight.

Associated as much with castration as with masculine potency, the lobster’s symbolic flexibility has kept it relevant through the ages. Where Dalí and Koons enjoy its capacity for sexual suggestion, the fashion industry exploits its status as a luxury object, recalling its role in the still life tradition. While the lobster may currently appear as a mascot for Peterson’s reactionary philosophy, contemporary artists offer a welcome counter-perspective. Goyette, Curtiss and Pigott’s playful, queer pieces give the lobster a chance to resist this appropriation, using their different styles to open up new ways of seeing this familiar yet seemingly inexhaustible symbol.