Has historic surrealism been an inspiration for your practice?

I’ve always felt a strong kinship with artists who work with the unconscious, psychology and metaphysical ideas. Magritte is a big influence, the archetypal quality of his images always stuck with me and I enjoy the repressed emotions in his works. But there are a lot of artists who have connections to surrealist imagery but don’t belong to the movement. Marcel Duchamp (especially his Etant Donnés), Louise Bourgeois or, more recently, Robert Gober; they are all very important to me. With the exception of Frida Kahlo, I wasn’t at all familiar with female surrealism until the Dreamers Awake show at White Cube Bermonsey [where I exhibited]. I was thrilled to read the curator Susanna Greeves’s catalogue essay. She shines a light on some of the female artists at the origins of the movement and how they tackled the question of what a woman is, in the times they lived in.

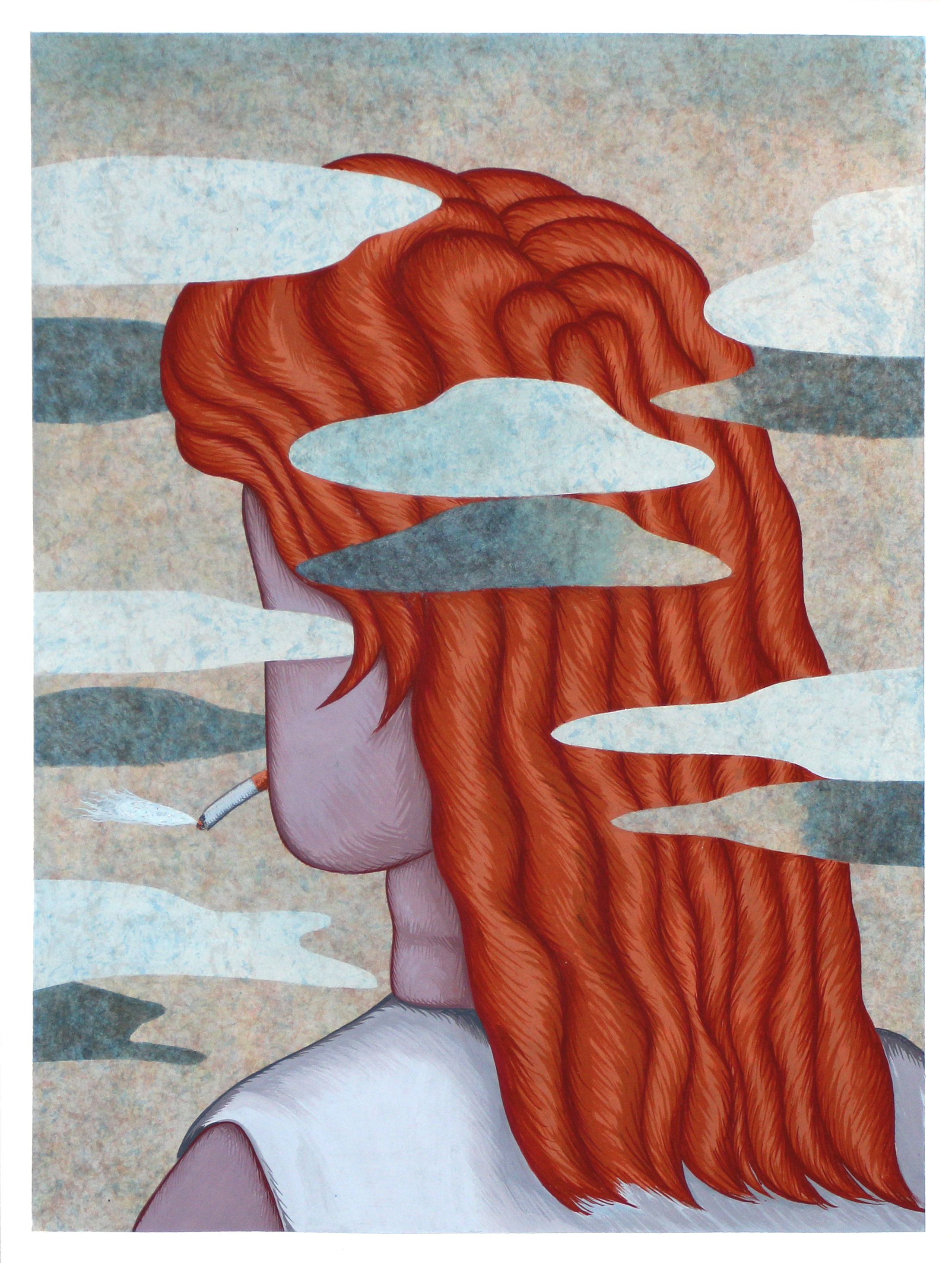

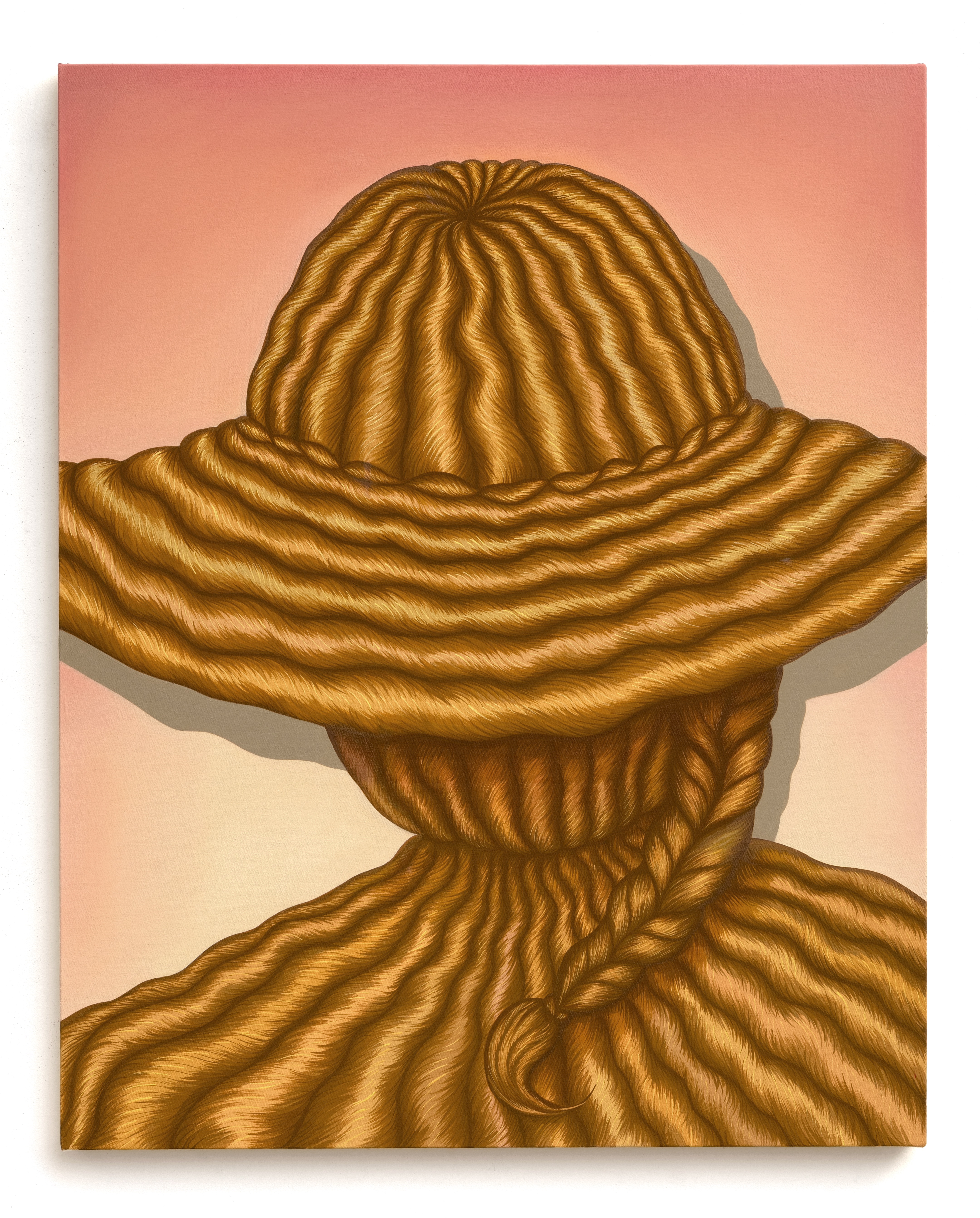

There’s a subversive sexuality in your work; the ropes of hair, full fleshy bodies, hairy food and incredible manicures. Where do these motifs come from?

The hair motif is connected to something deeply personal, but it’s also tied to universal symbols. Hair evokes something primordial, it’s a part of our body that grows relentlessly and that we can cut off without pain. It refers to something animalistic, like fur. My work deals with ideas of the wild and the tame; nature and culture in the female psyche. Hair is eventually combed and braided and nails manicured. Women transcend these physical attributes for seduction and status. As a woman, I am interested in the way we fashion our own image, to be seen, not only by men, but the world.

“There is a satisfaction to painting––looking at facial traits and expressions––but I didn’t feel like giving into that satisfaction”

Your figures always appear to be anonymous, with no facial features and presented from unusual angles. Are you creating a universal figure?

You are absolutely right. I realized that painting faces made me feel very uncomfortable. I didn’t want my subjects to be portraits; too specific or personal. There is a satisfaction to painting––looking at facial traits and expressions––but I didn’t feel like giving into that satisfaction. I felt that I could allude to my characters’ feelings or personalities by dropping visual clues here and there, and I leave it to the viewer to piece the image back together. The fragmentation of the self is a big theme in my work, so representing partially obscured faces became unavoidable.

There seems to be something compellingly sinister, yet strangely humorous, lurking in your paintings. Is that balance something you are looking to convey?

I am always attracted to the sinister and the dark. If I was a movie director I think I would make horror movies or thrillers! I am a big fan of Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch. Maybe balancing humour with darkness is a way of taming my fears by making fun of them; making them a little grotesque. I also like making something repulsive attractive, and vice versa. It’s like the alchemical process of transforming opposites. It’s also about reclaiming a symbolic power over what we can’t control in life.

Are anxiety and angst-inducing emotions something you relate to in your practice?

That question rekindles something I had completely pushed to the background. I initially started making art as a means of expressing my anxieties and my fear of death. But over time, the practice itself, which became a source of release, overtook my fears. I have made art on such a regular basis for most of my life that I almost forgot that it originally came from a place of existentialism. My angst still comes through in my themes, however the practice is meditative, fun and challenging now.

“In Japan, I came to understand that my strength lies where my pleasure is and that spending days drawing weird cartoons is totally fine”

Could you tell me a little bit about your colour palette? You often use very vibrant hues, sometimes juxtaposed against dramatic shadows.

My husband used to say I must be colour blind, and I do think it took me some time to feel comfortable with colours. Now I enjoy purposely using awkward, clashing combinations. The dramatic shadow came later, helping to add a shallow depth to my compositions and making them look oddly staged, like the theatre of one’s mind.

How did your time in Tokyo influence your practice?

I lived there in my first year after graduating. It was very formative because I suddenly became aware that I could do whatever I wanted artistically. Somehow, I never felt that freedom at art school. France is a very academic country and I had many voices in my head: my teachers, students and the weight of art history. In Japan, I came to understand that my strength lies where my pleasure is and that spending days drawing weird cartoons is totally fine. My year in Tokyo was very hard in many ways as I was extremely isolated and completely lacking in self-confidence. At the same time, it was there that I started to perceive a possible path for myself as an artist.

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35