When surveying the sunbaked landscapes of South Africa, it is possible that the view may be interrupted by a disturbance of vivid, geometric pattern. These vibrant bursts are the houses of the Ndebele tribe, decorated in bold lines that encapsulate sharp proclamations of colour. They feel like a dazzling signal; a declaration of territory, perhaps, or a friendly welcome.

Not to be confused with the Ndebele tribe of Zimbabwe, the Transvaal Ndebele of South Africa are composed of Northern and Southern groups, the latter of which is made up of Manala and Ndzundza populations. It’s the Ndzundza Transvaal Ndebele who are known for their striking wall painting and decadent beadwork.

Historically recognised as fierce warriors, they retained agency over their land until 1883, when a territorial dispute with the encroaching Boer population resulted in Ndebele families being distributed to work as indentured labour for Boer farmers. This forced dispersal was only accelerated in the latter half of the twentieth century due to the creation of KwaNdebele homeland as part of apartheid policy. As this imposed migration grew, Ndebele expression of identity proliferated.

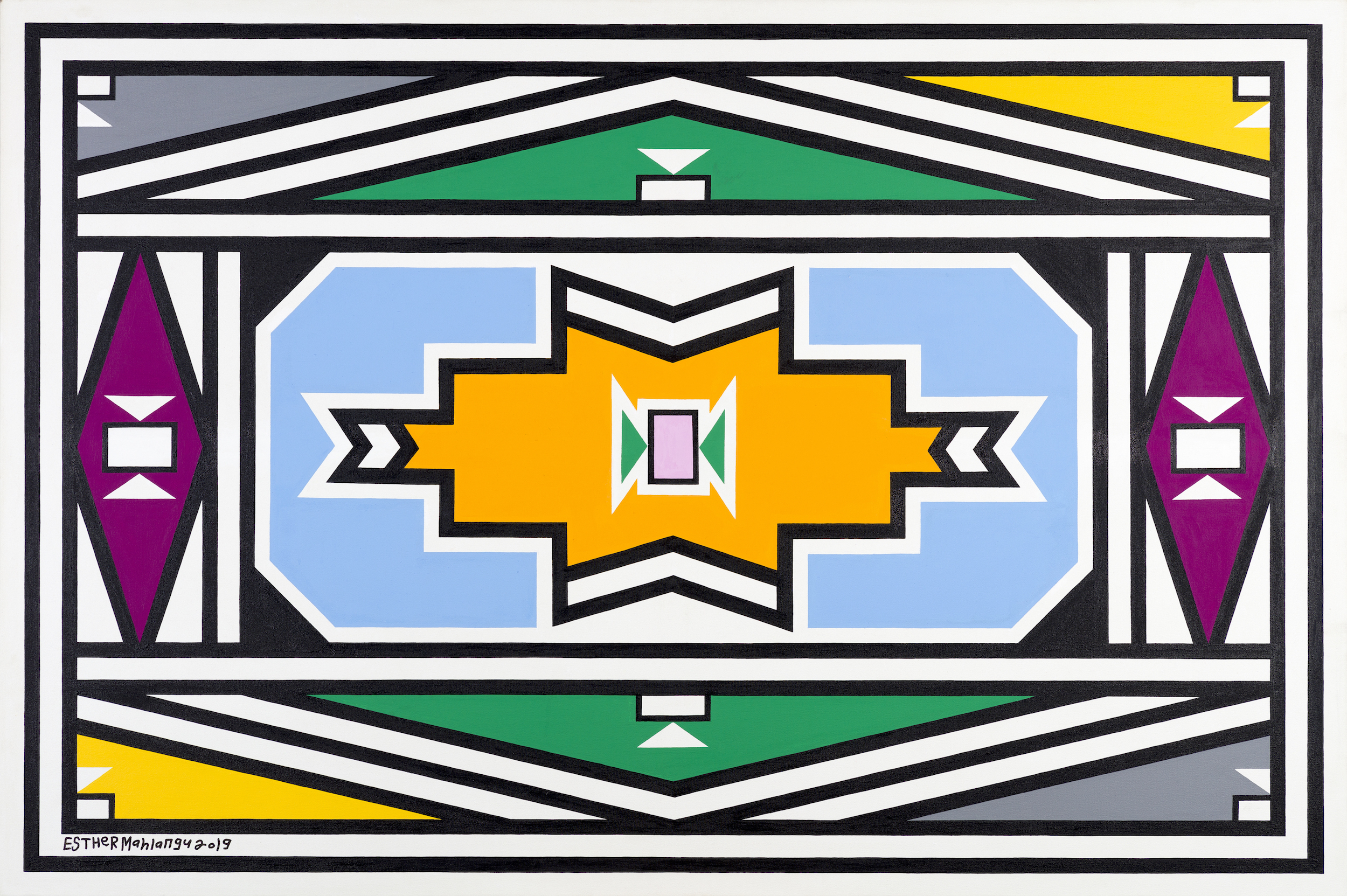

Esther Mahlangu, Abstract 01. 2020

Slowly, a new women-led culture began to emerge of painting homesteads with patches of colour, starkly delineated within black outlines. While at first the women used earth-toned natural pigments, the increase in availability of acrylic paint after World War 2 ensured an acceleration in the hues’ vibrancy, resulting in the buoyantly coloured homes we see today.

There is some debate over whether the particular design of this visual tradition is directly symbolic. While some researchers have tried to glean meaning from the shapes, others have accepted the decorative nature of the work. This is also a symptom of the colonial gaze of academia: the Ndebele community’s distrust of the other has resulted in an unwillingness to speak to researchers about such a personal manifestation of culture. Given the population’s history with the Boers, this attitude is hardly surprising.

“They feel like a dazzling signal; a declaration of territory, perhaps, or a friendly welcome”

In recent years however, Dr Esther Mahlangu, an Ndebele artist, has brought visibility to the culture on her own terms, even bridging the gap with academia by being awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Johannesburg. Having risen to fame at 54 years old, she is set to celebrate her 85th birthday with a retrospective at Melrose Gallery, as well as (in the spirit of 2020)

Mahlangu’s colour-rich, boundary straddling designs are directly derived from Ndebele visual tradition. She learned how to paint murals from the age of 10, keen to follow in the footsteps of her mother and grandmother. Mahlangu began to transition from walls to canvas as her medium of choice, and her practice evolved to adorn found objects such as war helmets, motorbikes and mannequins with the signature Ndebele visual language. Mahlangu describes the “straight lines and balance of each piece” as “non negotiable… an essential part of Ndebele painting”. She explains that she wants to pass the tradition onto future generations, so they can understand the origins of the art.

- Esther Mahlangu. Photo by Clint Strydom

She has certainly gained visibility, from painting BMW’s signature art car to embellishing the tails of British Airways planes. The Ndebele patterns have leapt from the walls of their homes into a global phenomenon. Since Mahlangu made her debut in the late eighties at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, she has exhibited at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, The British Museum and the National Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian Institution. While appreciative of her global success, she has surprisingly enjoyed very few solo exhibitions in her home country of South Africa, making Esther Mahlangu 85 all the more timely.

“The thirst for Ndebele designs in the West is ironic given their origins as a resistance to colonialism”

The Ndebele visual tradition has inspired many a muralist, from urban wall artists in Africa, to the acclaimed French artist Camille Walala. The simplicity of the geometric shapes make them ripe for appropriation, and often the motifs are used to integrate a particularly African or ethnic identity into existing styles. The thirst for Ndebele designs in the West is almost ironic given their origins as a resistance to colonialism and the Western gaze.

To return to the idea of Ndebele homesteads as a declaration of territory, is to recognise that land is political. South Africa’s history is steeped in entrenched ideas of race, battles over territory and against this backdrop, a fervent need to preserve cultural identity. The emboldening of Ndebele traditions through beadwork, clothing, ceremony and mural art is not only a form of resistance, but a bid to claim space. Dr Mahlangu, it could be said, has continued this work of visibility through the upward trajectory of her career, yet as Ndebele aesthetics are integrated into mainstream visual culture, only time will tell if this community receives the credit they deserve.