Trigger Warning: This article contains mentions of suicide, grief, and sexual abuse

Families are funny things. The word itself contains a hothouse of associations and expectations: security, support, comfort, tradition, hierarchy, longevity. But while conventional definitions of family are so idealised and entrenched, the reality is rarely straightforward. Currently showing at Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland, Chosen Family – Less Alone Together visualises the concept of family in all its complications and contradictions. Curated by Nadine Wietlisbach with the support of Katrin Bauer, the exhibition draws on international loans and works from the museum’s collection, as well as the personal photo albums of families in Winterthur and across Switzerland.

Some of the featured photographers delve into their own family histories, making sense of an often difficult past. Some present themselves and their family members in staged settings, breaking apart and re-framing family structures in order to reflect on prescribed roles. Other photographic explorations focus on the idea of the elective family, those tight-knit communities forged outside biological bonds which challenge received notions of what a family should be. Chosen Family

sheds light on grief, estrangement, individual and collective trauma, role reversals, queer constellations, and many poignant topics in between. Here are some highlights.

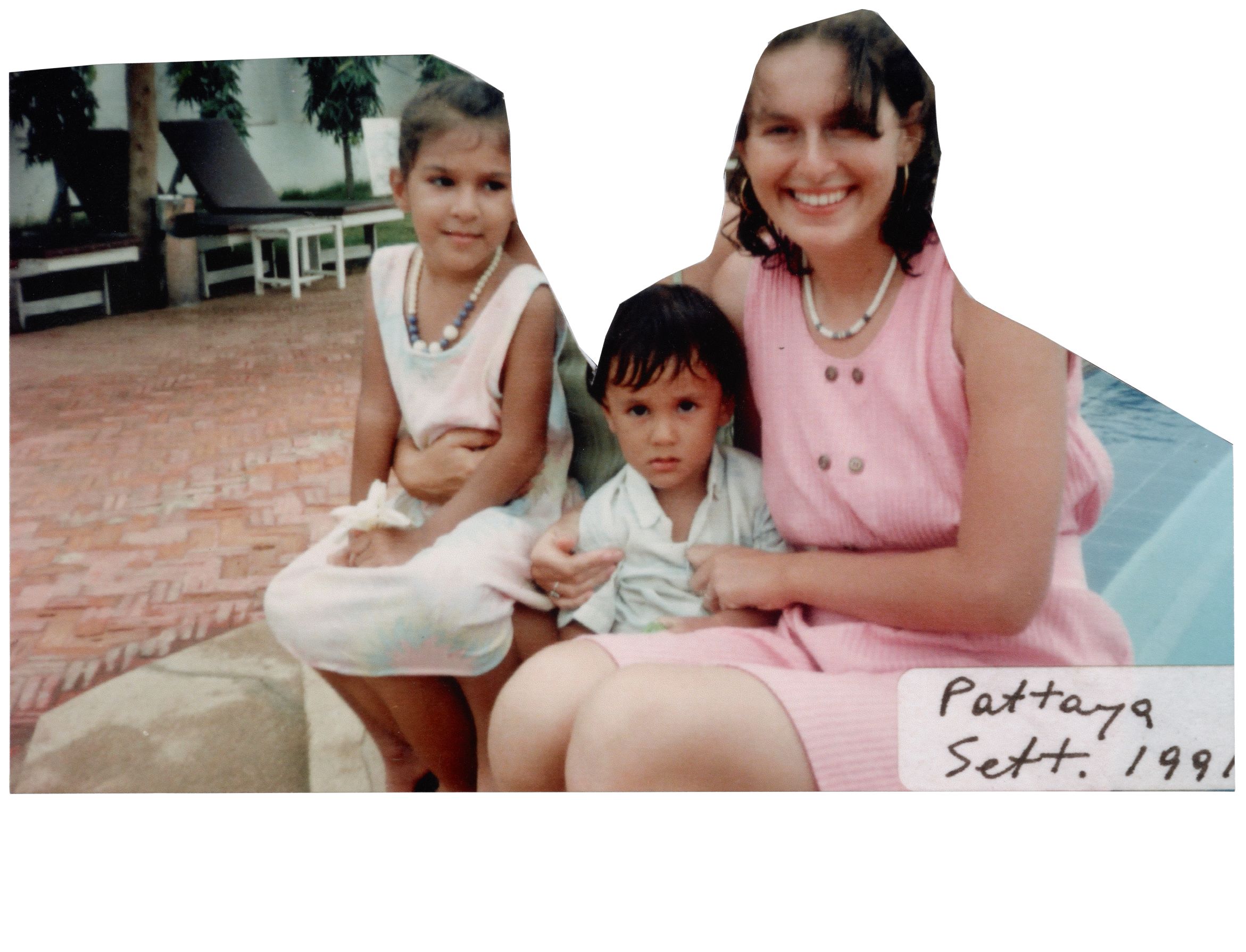

Alba Zari, Family Archive, from the ongoing series Occult, 2019 and onwards

In Occult, Alba Zari embarks on a forensic photographic exploration of her upbringing. The Italian artist was born into the fundamentalist Christian sect The Children of God, which her grandmother and mother were indoctrinated into aged 33 and 13 respectively. The sect was known for separating children from their parents, encouraging sex with minors, prostituting women as a means of recruiting new members, and carrying out colonialist practices under the guise of Christian missionary work. Using family photo albums, archive images from other members, and official texts and visuals of the sect, Zari pieces together the fragments of a personal and collective trauma, and denounces the sect’s propaganda machine.

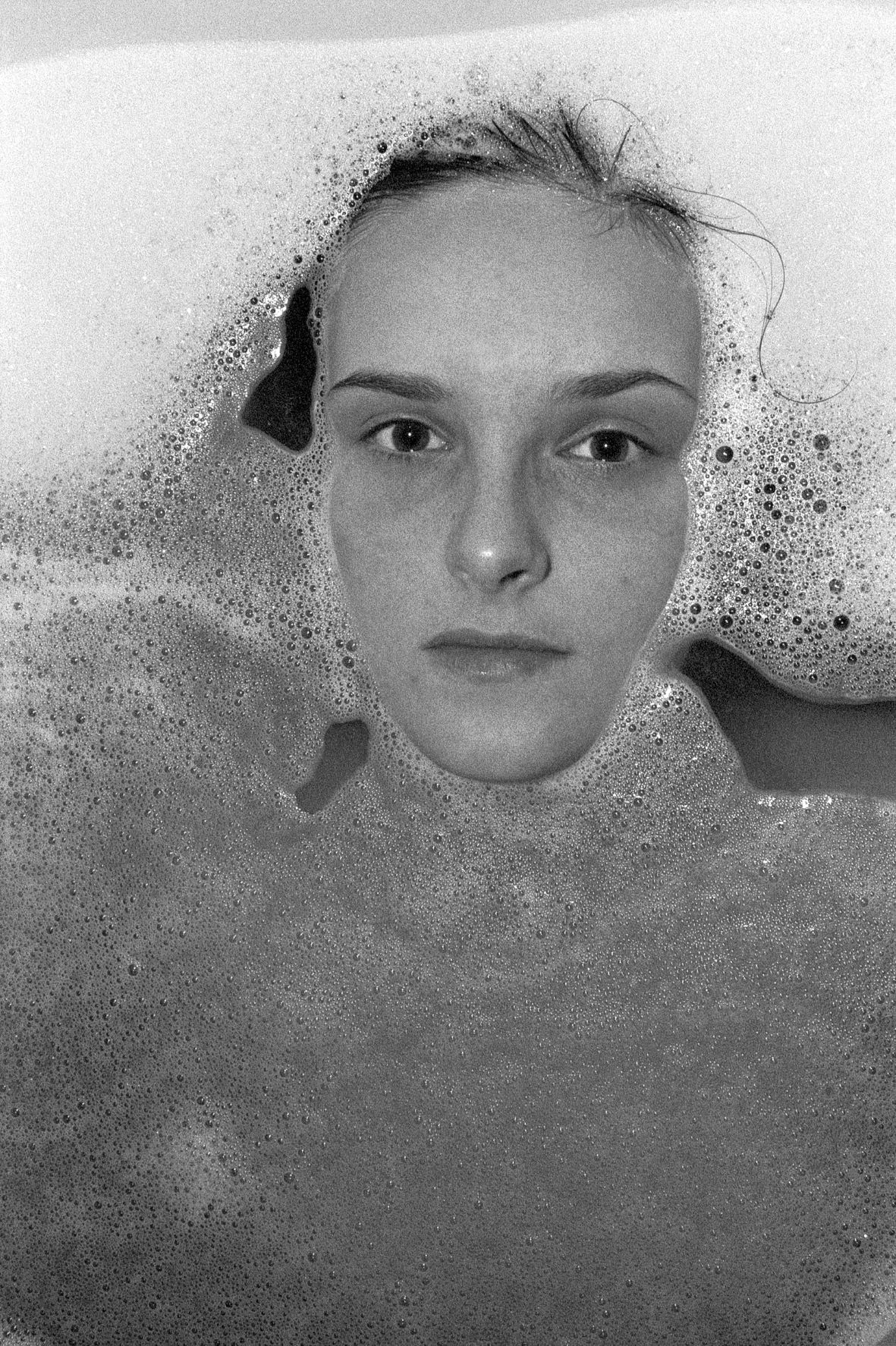

Seiichi Furuya, Graz, 1979, from Portrait of Christine Furuya, Graz/Wien, 1978–1984

Over a period of several years, Japanese photographer Seiichi Furuya took thousands of portraits of his wife Christine Gössler. “In facing her, in photographing her, and looking at her in photographs, I also see and discover ‘myself’,” Furuya said in 1980. When Christine took her own life five years later, Furuya returned to the portraits as a form of grief work, repeatedly making new compilations of them over the decades. It was a way for him to find the “truth” of what happened. Even though he was always left searching, his project evinces the power of photography as a medium for mourning.

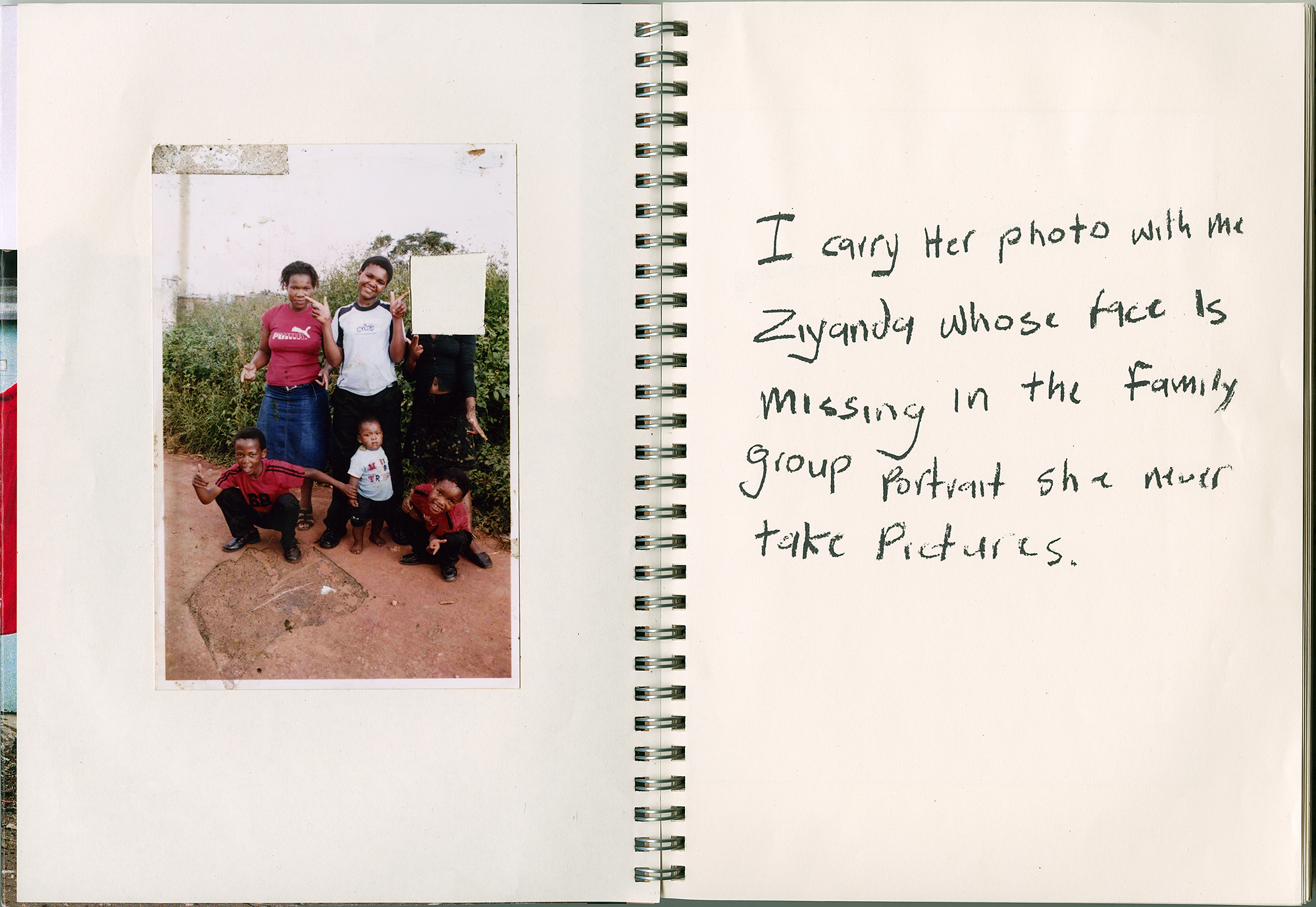

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from I Carry Her Photo with Me, 2017

In 2002, when Lindokuhle Sobekwa was seven, his 13-year-old sister Ziyanda ran away from their Johannesburg home. She returned more than a decade later, dying shortly afterwards from illness. The only photograph Sobekwa had of Ziyanda was a family portrait, from which her face was cut out to use at her funeral. Sobekwa’s handmade photobook I Carry Her Photo with Me is his attempt to weave together her story. He sought out people who had known Ziyanda in order to retrace her life. “The project is really for myself, but also for my family and anyone who can relate to it,” he says. “The experience of disappearance, of losing someone, and of grief is a universal thing.”

Pixy Liao, It’s Never Been Easy to Carry You, 2013, from Experimental Relationship, 2007-ongoing

“As a woman brought up in China, I used to think I could only love someone who is older and more mature than me, who can be my protector and mentor,” says Brooklyn-based artist Pixy Lao. Then in 2007 she met her current boyfriend Moro, a man five years her junior: “I felt that the whole concept of relationships changed, all the way around. I became a person who has more authority and power.” Through staged scenarios performed by the couple, her photo series Experimental Relationship plays with “the alternative possibilities of heterosexual relationships”. Liao assumes the position of strength in this image, a comically literal representation of the emotional weight of love.

Charlie Engman, Blue Mom, 2017, from MOM, 2009–ongoing

Charlie Engman started photographing his mother Kathleen in 2009 while on a break from college. What began as a casual process evolved into an intense and ongoing collaboration. Muse, model and equal in the image-making process, Kathleen poses in myriad settings (some mundane, some fantastical), her identity transformed beyond recognition at times through costume and makeup. Their photographs push the boundaries of familiarity and question what it means to know your subject, challenging the one-dimensional image of motherhood.

Diana Markosian, The Arrival, 2019, from Santa Barbara, 2019–2020

In 1996, when Diana Markosian

was seven years old, her mother woke her in the middle of the night and announced they were leaving Moscow. Inspired by the sun-drenched vision of California in the 1980s soap Santa Barbara, her mother had used a matchmaking agency to find a man who could help her resettle there. “The Soviet Union had long collapsed, and by then, so had my family,” says Markosian. “We left without saying goodbye to my father, and the next day landed in a new world.” To reconcile this history, Markosian cast actors to play her family, collaborating with the original scriptwriter of Santa Barbara to reimagine their journey in staged photographs and narrative video. This image depicts the moment where the fairytale of the American Dream ends and the harsh reality begins.

Dayanita Singh, Shalu dances on Ayesha’s second birthday, 1991, from The Third Sex Portfolio, 1989–1999

In 1989, in the Turkaman Gate neighbourhood of Delhi, Dayanita Singh met and began photographing Mona Ahmed, who identified as a hijra or “third gender”. The pair developed a friendship and Singh was allowed into the closely-guarded hijra community to photograph the extended birthday celebrations of Mona’s adopted daughter, Ayesha. Rich with whirling dancers, music and laughter, Singh’s black-and-white photos are a joyous snapshot of a community that rejects gender binaries and forges familial bonds of its own. Criminalised under British colonial rule, hijras still face discrimination and persecution today.

Anne Morgenstern, from Whatever the Fuck You Want, 2018–2020

For queer sex magazine, Whatever the Fuck You Want, German photographer Anne Morgenstern lensed queer intimacy with tenderness and candidness in equal measure. Devoted to sexual openness, the magazine aimed to “close the gap between heteronormative school education and unrealistic porn; that is, where life actually takes place”, to quote co-editor Florian Vock. Viewed within Chosen Family, Morgenstern’s sensual photograph of two figures enveloped in a passionate embrace, their entwined skin warmed by golden light, speaks to the bonds forged outside heteronormativity, and the strength of elective families within the queer community.

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs

Chosen Family — Less Alone Together is at Fotomuseum Winterthur until 16 October