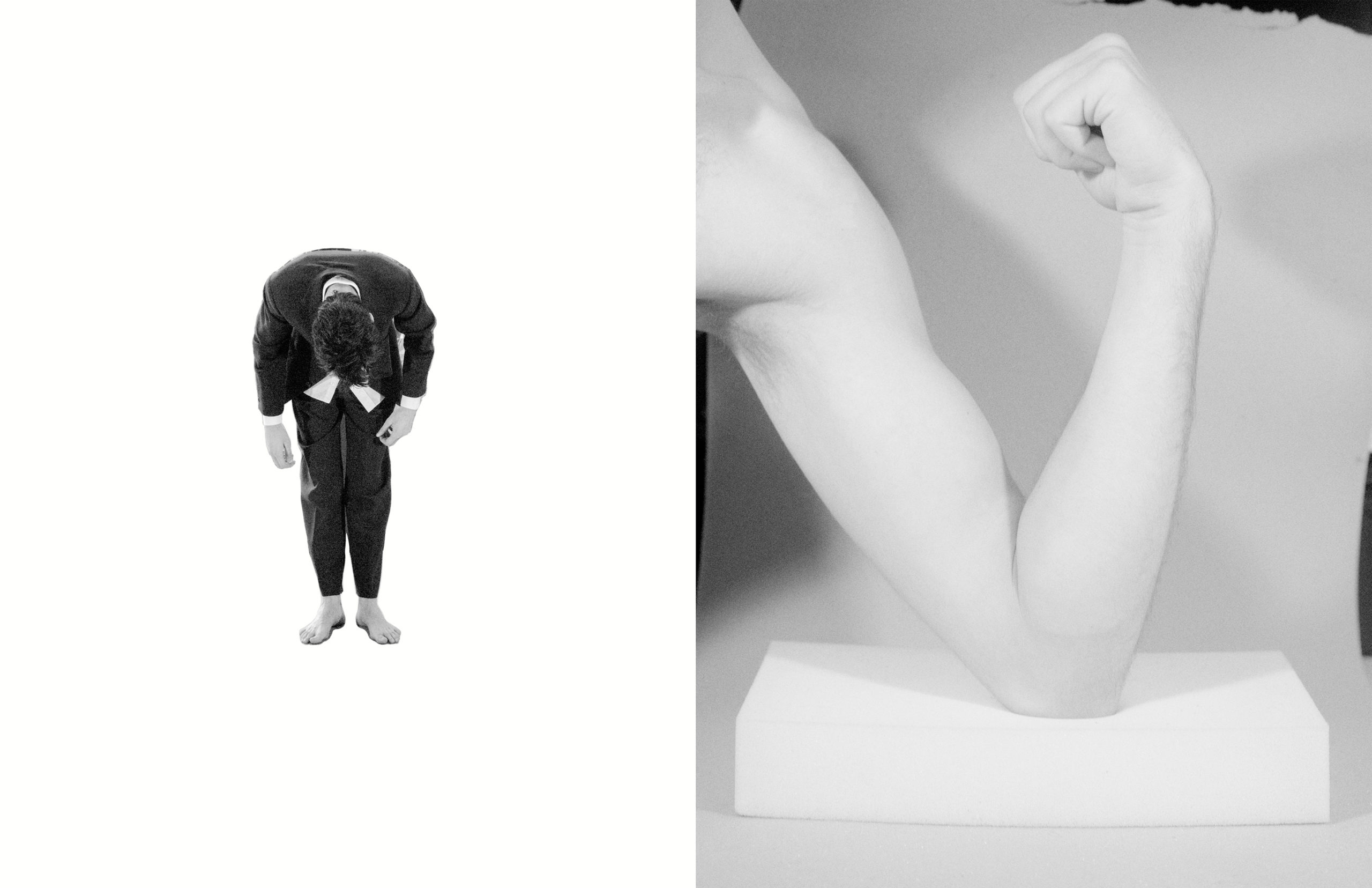

Strong handshakes, flexed biceps and clenched fists; these are the gestures that we have come to associate with masculinity. Photographer Romain Duquesne has decided to tackle the gendered significance of these symbols head-on in his latest body of work, culminating in his book Hi, Hello!The title itself is a call for human connection, which Duquesne further compounds with an interior inscription that reads, “for men who are boys, a cry to connect”. This poetic sentence underscores the nature of his images, which eschew the bombastic tropes usually associated with hyper-masculinity in favour of sensual, occasionally absurd shots that evoke vulnerability, beauty and introspection.

For one, the presence of various fruits including melons and grapes are a call back to teenage antics: “I was thinking about the ridiculous silliness of teenage boys stuffing bananas in their trousers or holding up melons to imitate breasts” he explains. While these allusions are usually crude, Duquesne creates unexpected compositions that make you question how and why visual language is asserted—particularly in matters of sex and gender performance.

“His images eschew the bombastic tropes usually associated with hyper-masculinity in favour of sensual shots that evoke vulnerability”

At times art historical allusions come to the fore, such as the vignettes of clasping hands that are reminiscent of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. Elsewhere, shots of fractured nude reflections are infused with a tender intimacy that resonate with Francesca Woodman’s mirror-based self- portraiture.

Beyond the images themselves, the book’s structure further expresses the complexities of masculinity. For example, a shot of two men on a sofa with their fingers barely touching is ferociously cropped and runs over the page edge, making one companion significant in his absence. Several images are also presented as cut-outs, much like a theatre set or shadow puppetry. Others depict taut limbs that are softened by their visible background staging—the irony of masculine performance is made painfully evident once more.

Unsurprisingly, Duquesne was keen to explain to his models (who were predominantly friends) that this was not going to be a “cute little portrait session”; the project would demand a certain level of trust and intimacy in order to transcend didactic or overtly eroticised readings. However, that is not to say that a good dose of awkwardness didn’t garner great results. While working with one of his friends, who is an actor, the interaction seemed stilted, until the model suggested he improvise. “It was very unexpected,” Duquesne explains. “He suddenly constructed an entire character, who was a hyper-macho guy accusing another man of ‘looking at his girl’.”

“This was not going to be a ‘cute little portrait session’; the project would demand a certain level of trust and intimacy”

The outcomes, which open and close the book, are strangely ambiguous. This moustachioed figure conveys an eccentric mix of anger, sexual energy and farcical gesture, as if he could burst out laughing or swing a punch in the next breath. It is a tenuous balance that ultimately captures the confounding strictures of “masculine culture”, offering something of a hardened shell that protects the beauty and intimacy within.